Archived information

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Partnerships with Canadians Governance Program Evaluation - 2008-2012 - Final Report

November 2013

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Program Context

- 3.0 Findings - Development Results

- 4.0 Findings - Management Factors

- 5.0 Conclusions

- 6.0 Recommendations

- Appendix A: Terms of Reference (summary)

- Appendix B: Evaluation Methods

- Appendix C: Description of Universe and Sample

- Appendix D: List of Documents Reviewed

- Appendix E: Tanzania Case Study

- Appendix F: Management Response from PWCB

- Subject Index

- References

Acknowledgments

The Development Evaluation Division wishes to thank all who have contributed to this evaluation for their valued input, their constant and generous support, and their patience. Our thanks go first to the independent team of the firm Results Based Management Group, made up of Michael Miner, Werner Meier and Melinda MacDonald. The Results Based Management Group was responsible for data collection, analysis and initial report writing.

The Development Evaluation Division would also like to thank the Partnerships with Canadians Branch Governance Program team for their valuable support. We also greatly appreciate the valuable input and time of our partners in Canada and in the field. In particular, we thank the organizations who facilitated and hosted the case study in Tanzania.

From the Development Evaluation Division, we wish to thank Tricia Vanderkooy for managing the evaluation and contributing to report writing. We also thank Andres Velez-Guerra, Team Leader and James Melanson, Director, for editing the report and overseeing the review.

Caroline Leclerc

Head of Development Evaluation

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- CARICOM

- Caribbean Community

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- DAC

- Development Assistance Committee (of OECD)

- DFAIT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade

- DFATD

- Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada

- OAS

- Organization of American States

- OECD

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

- PWCB

- Partnerships with Canadians Branch

- RBM

- Results Based Management

Executive Summary

Background

Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD)Footnote * advances Canada's commitment to freedom, human rights and rule of law through support to strengthening both the democratic institutions of states, and citizen and civil society participation. The Partnerships with Canadians Branch (PWCB) engages with Canadian organizations to support programming in five key areas: 1) Governance; 2) Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability; 3) Human Development; 4) Engaging Canadians; and, 5) Knowledge Creation and Sharing.

Objectives

The objectives of this evaluation of PWCB's Governance Program are:

- to examine the results achieved by the PWCB Governance Program from 2008-2009 to 2011-2012 relative to the objectives articulated in planning documents;

- to assess the PWCB Governance Program's overall performance in achieving these results; and

- to document findings, conclusions and recommendations to improve performance.

Methodology

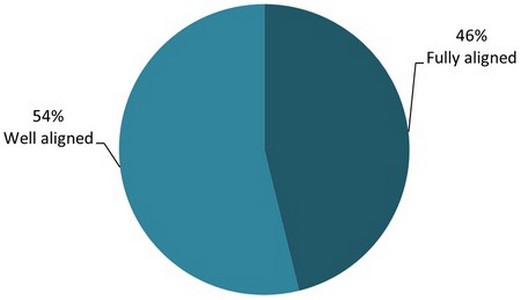

This evaluation covers a program comprised of 77 governance projects in 81 countries with recorded disbursements of approximately $170 million between 2008-2009 and 2011-2012. They pre-date the introduction of the call for proposals process, which was introduced in late 2010. Using a representative sample of 42 projects, the PWCB governance program was assessed according to eight criteria: 1) relevance, 2) effectiveness, 3) sustainability, 4) gender, 5) environmental sustainability, 6) coherence, 7) efficiency, and 8) performance management. The criteria, questions and indicators are detailed in the evaluation matrix (Appendix B).

The evaluation reviewed the program's progress towards achieving the four "Elements of Democratic Governance:"Footnote 1 Accountable Public Institutions, Freedom and Democracy, Human Rights, and Rule of Law. Evaluation methods included review of past project evaluations and project-performance documents, interviews with CIDA officers, interviews with Canadian partners, and a case study of PWCB governance program activities in Tanzania.

Findings

Findings for each of the eight criteria are as follows:

Relevance – Overall, the PWCB governance program is very relevant in responding to beneficiaries' needs, especially when Canadian partners have developed a collaborative and mutually respectful relationship with their host country partners. With only a few exceptions, the needs of local partners and beneficiaries were well integrated into projects. The governance program is characterized by substantial stakeholder involvement, including local government partners, service-delivery agencies, civil-society organizations and private-sector partners.

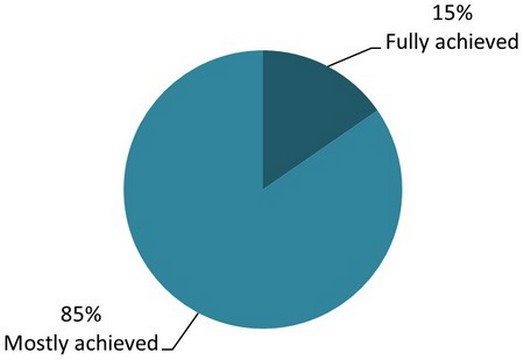

Effectiveness – Governance projects are mostly concentrated at the community and local government levels. Relatively fewer outcomes were targeted or achieved at the national government level. The most successful outcomes are in promoting freedom and democracy and building accountable public institutions. There was less program activities and fewer outcomes in the areas of human rights and the rule of law. Successful partner models feature mutually agreed-upon outcomes, focus on a specific area of intervention, and involve a wide range of stakeholders. Local partners have valuable cultural and local knowledge of the governance realities on the ground, which enable them to identify interventions that are most likely to work in the specific context.

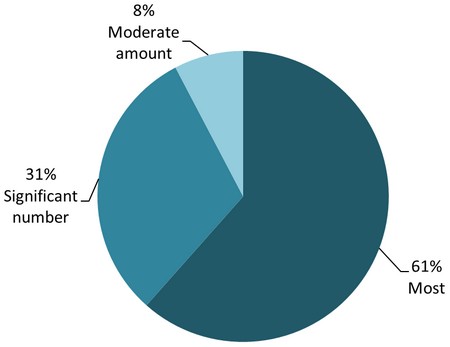

Sustainability – Projects are more likely to be sustainable when benefiting from local ownership and embedded capacity building within partner institutions. Techniques that contribute to sustainability include rooting learning within strengthened partners' offices; "train-the-trainer" programs including extensive mentoring; building national and regional networks using alumni; and, ensuring that projects have exit plans. Many Canadian partners are very effective in building long-term relationships with partner organizations, but are less effective in working with local partners to design an exit strategy to ensure the sustainability of results after CIDA funding ends.

Gender Equality – Projects demonstrated mixed use of gender analysis tools, mixed levels of integration of gender into policy frameworks and mixed reporting of gender results. Projects that integrated gender into planning and management reported significant achievements in gender equality for all three objectives of CIDA's Gender Equality Policy. Beyond the effective use of gender tools to collect and report on data, there was a positive correlation between the projects' relevance to the local context and local needs of beneficiaries and the achievement of gender equality outcomes.

Environment – Most projects did not require an environmental assessment because they did not focus on environmental issues. For those that did have anticipated environmental impacts, most Canadian partners prepared very complete Environmental Assessments. A few Canadian partners need to build capacity in environmental assessment especially for local partners.

Coherence – There is little coordination or harmonization of PWCB projects either with CIDA-supported projects and/or with relevant national and donor supported governance projects. There are some good examples of coordination at the regional level. There are opportunities for coordinating governance program activities among partners at the country level.

Efficiency – Large Canadian partners are decreasing their administrative overhead due to diversified sources of funding and economies of scale, whereas mid-sized or small non-governmental organizations find it difficult to absorb administrative costs. Small partners also have difficulty raising the amount of revenue required by PWCB's new cost-sharing model. The absence of early notice of when calls for proposals are released makes it difficult for Canadian partners of all sizes to do long term planning and maintain their long-term partnerships with host country partners or maintain consistency in program activities.

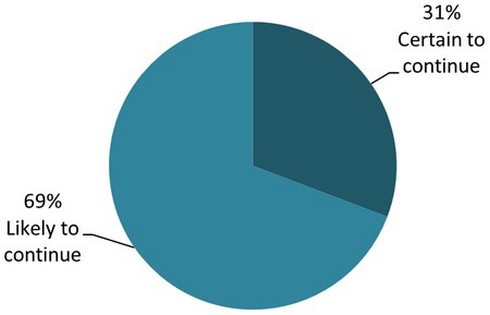

Performance Management – Many Canadian partners use Results-Based Management (RBM) tools and other techniques to monitor their own performance. The PWCB governance program's absence of an agreed logic model, performance measurement framework and performance monitoring strategy made the strategic management of the program more difficult. (This must however be understood in the context of several changes to the program's place in CIDA's organisational structure during the review period.) While monitoring and evaluation coverage can be considered adequate, the evaluation did not find evidence that a risk based monitoring strategy underlies conduct of these activities.

Conclusions

This evaluation draws the following conclusions:

- Relevance – The PWCB Governance Program is highly relevant to locally identified needs and priorities. Relevance is facilitated through trusting relationships between Canadian organizations and their local counterparts in developing countries.

- Effectiveness – PWCB partners demonstrated positive achievements in building accountable public institutions and promoting freedom and democracy. Most governance projects target local and community level issues, with relatively fewer interventions targeting national level issues. Less program activities and fewer achievements were found in the areas of human rights and promoting the rule of law.

- Sustainability – PWCB's Canadian partners generally have strong relationships with partners on the ground, contributing significantly to local ownership . Nonetheless, projects generally do not have exit plans for when CIDA funding ends. It should be noted that the longer time frames needed to achieve governance results, and the limited duration of project funding, pose particular challenges to sustainability.

- Gender Equality – Projects that were more attuned to local needs and context displayed greater success in gender equality. However, most governance projects did not integrate gender equality throughout program activities.

- Environment – Most governance projects did not address environmental issues. Capacity building in environmental assessment would benefit the partners whose projects do have environmental implications.

- Coherence – Most PWCB partners do not coordinate their governance activities with other organizations, although they are very interested in doing so. Harmonization could add substantial value to existing investments, as PWCB partners could leverage their local efforts through countrywide coordination.

- Efficiency – Smaller organisations had difficulty finding economies of scale and meeting CIDA's matching fund requirements.

- Performance Management - Canadian partners use performance-measurement to inform decision-making. The PWCB governance program does not have finalized results-based management tools for the program as a whole.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are intended to strengthen the PWCB governance program:

- Coherence and Effectiveness – For improved effectiveness, and where appropriate, small project initiatives with communities and local government should be linked with national governments to amplify results. PWCB and CIDA field staff should facilitate connections among PWCB partners, bilateral and other donors' projects in specific countries and regions.

- Sustainability and Exit Strategies – PWCB should encourage and support partners in developing exit strategies for when project funding ends, to ensure the sustainability of results. Since achieving results in governance sometimes requires long and uncertain timeframes, allowing flexibility to extend or increase support to projects that demonstrate exceptional potential should be considered.

- Gender Equality – To improve gender data collection and outcomes, PWCB should encourage training for Canadian partners on gender equality tools and analysis. Along with meaningful consultation, PWCB should require partners and projects to demonstrate systematic gender analysis throughout project planning and implementation.

- Performance Management – PWCB should finalize the Governance Program Performance Management Strategy, including a logic model, a performance measurement framework, and a risk based monitoring strategy.

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Evaluation Purpose and Objectives

Canada supports democracy-building efforts in many developing countries, especially through improved governance. CIDA advances Canada's commitment to freedom, human rights and rule of law through support to strengthening of democratic institutions of states, and citizen and civil society participation. Through its Partnerships with Canadians Branch (PWCB), CIDA conducts programming in five key areas: (1) Governance; (2) Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability; (3) Human Development; (4) Engaging Canadians; and, (5) Knowledge Creation and Sharing.

This evaluation of PWCB's Governance Program has a learning and accountability purpose, namely:

- to provide Canadians, Parliamentarians, Ministers, central agencies and deputy-heads with a neutral, evidence-based assessment of program performance; and

- to support policy and program improvements by helping to identify best practices.

The objectives of this evaluation are:

- to examine the results achieved by the PWCB Governance Program between 2008-2009 and 2011-2012 relative to the objectives articulated in planning documents;

- to assess the PWCB Governance Program's overall performance in achieving these results (based on relevance, effectiveness, sustainability, crosscutting themes, coherence, efficiency, management principles, and performance management); and,

- to document and disseminate findings and conclusions and formulate recommendations to improve performance.

1.2 Methods

The PWCB governance program was assessed according to eight criteria, namely: 1) relevance; 2) effectiveness; 3) sustainability; the crosscutting themes of 4) gender and 5) environmental sustainability; 6) coherence; 7) efficiency; and 8) performance management. The criteria, questions and indicators are detailed in the attached evaluation matrix (Appendix B).

The governance program moved three times within CIDA's organizational structure during a relatively short period, posing management challenges. Although the PWCB Governance Program had two logic models developed, neither had received official approval. It was therefore difficult to determine which goals or objectives the program's performance should be assessed against. Thus, the evaluation reviewed the program's progress towards achieving the four "Elements of Democratic Governance," which are Accountable Public Institutions, Freedom and Democracy, Human Rights, and Rule of Law.Footnote 2 The evaluation methods included document review of past project evaluations and additional performance and project documentation, interviews with CIDA officers and Canadian partners, and a country case study of governance program activities. Tanzania was selected for the governance case study due to its concentration of past and ongoing governance projects. In addition to project-level information, program-level data was gathered through both interviews with PWCB staff and Canadian partners, and review and analysis of program-level documents. These were used to develop this report's high-level findings, conclusions and recommendations. Additional information on the methods used in this evaluation is found in Appendix B.

1.3 Description of Sample

This evaluation covers 77 governance projects in 81 countries with recorded disbursements of approximately $170 million between 2008-2009 and 2011-2012. These projects were funded through PWCB's former partnership funding mechanism for trusted Canadian organizations, and thus they pre-date the introduction of the call for proposals process in late 2010.

A review of the governance program statistical profile data, evaluation reports and other reference documents was conducted to develop a solid sampling framework. Given the degree of variability of partners, a randomly selected sample might have left out key investments, disproportionately misrepresenting different-sized partners and diminishing the usefulness of the evaluation. Therefore, a representative sample of 42 projects, based on the statistical profile of the governance program, was used for the evaluation. Appendix C contains further details regarding the evaluation universe and sample.

1.4 Evaluation Challenges and Limitations

This evaluation was challenged by the absence of a finalized program logic model. The program's effectiveness was therefore evaluated against its progress towards the four elements of governance described above. As well, there was limited baseline data. As a mitigation measure, the results of CIDA's prior governance evaluation published in 2008, which aligns with the beginning of the period covered by this evaluation (2008 - 2012), were used to benchmark CIDA's governance programming at the beginning of the evaluation period.

Due to budgetary limitations, the evaluation included only one field mission to one country (Tanzania). However, this limitation was mitigated by the inclusion of other evaluative information from projects in the sample, all of which included field visits in their methods.

2.0 Program Context

2.1 Governance Programming in CIDA

Governance has been a priority for CIDA for over 20 years. In 1996, the Agency released its Policy on Human Rights, Democratization and Good Governance.Footnote 3 The policy had several goals including strengthening civil society, strengthening the public sector and democratic institutions, promoting human rights, and supporting the rule of law. Since 1996, CIDA has disbursed $4 billion dollars to initiatives coded as "governance programming."

In 2006, CIDA's governance programming was brought together in the new Office for Democratic Governance. This unit led the Agency's work in governance programming and establishing partnerships with experts, organizations, and other government departments working in the governance sector. In 2009, this unit was closed and the program moved first to the Multilateral and Global Programs Branch and subsequently to PWCB. Thus, the program moved three times within a relatively short period, challenging its administration and reporting functions to adapt to different areas of the Agency's Program Activity Architecture.

In 2007, following the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs Report on Advancing Canada's role in International Support for Democratic Governance, the Government responded with support for governance programming through the introduction of an "integrated approach." This was described as "an innovative approach to democracy support that pays attention to local realities, and is coordinated through various actors, accounts for results and learns from past experience."Footnote 4 This was intended to tailor governance policies and programs to on-the-ground realities in developing countries.

In 2008, CIDA published a comprehensive review of its governance programming. The main conclusions were as follows:

- The Agency's performance in management and delivery of governance programs had been ineffective. The 1996 Governance Policy was highly regarded inside and outside the Agency but there had been an enormous gap between policy and implementation;

- CIDA had lacked the capacity to implement its own policy, to undertake high-quality work and learn from experience; and

- CIDA had not adjusted its operational structures, support systems, knowledge-sharing practices, project delivery or performance measurement tools, to enable it to respond to existing requirements, let alone new challenges. These difficulties had been compounded by a lack of clarity in internal accountabilities for managing governance as a sector or theme.Footnote 5

The 2008 review provides historical context for the present evaluation. It also summarizes the state of affairs for governance programming across the Agency, providing a good indication of governance programming in that period. Given that the present evaluation covers 2008-2012, the prior review serves as a benchmark of governance programming at the start of the evaluation period.

In 2009, the Government of Canada announced its five priorities for international assistance, one of which was advancing democracy. At the same time, the Government announced that governance would be a crosscutting theme to be considered in the development of its programs. An Agency-wide policy framework is currently being developed to guide programming in both advancing democracy and the integration of governance as a crosscutting theme. This policy framework will update the 1996 Policy on Human Rights, Democratization and Good Governance.

2.2 PWCB Governance Program

PWCB supports projects and programs that are designed and implemented by Canadian and international partner organizations in co-operation with their local counterparts in developing countries. PWCB also engages Canadians and builds knowledge about international development. In addition, it supports governance activities carried out by international nongovernmental organizations and multilateral agencies. The PWCB Governance Program is responsive in nature, working within the parameters of partner organizations' existing capacity and projects.

For several years, PWCB provided either core or project funding to trusted Canadian partner organizations carrying out governance program activities in developing countries, and it is from this period that the project sample evaluated in this report is drawn. In 2010, the partnership modernization framework introduced a call for proposals process, moving away from a continuous intake of unsolicited proposals, in order to provide equal access to information about funding opportunities for all potential partners. This process ensures that the most meritorious projects are selected for the most effective development results. The PWCB modernization restructured program activities into two overarching programs: "Partners for Development" and "Global Citizens." The governance program falls under "Partners for Development." However, projects emerging from this new process do not form part of the sample evaluated in this report.

2.2.1 Governance Projects and Spending

Between 2008-2009 and 2011-2012, the PWCB governance program disbursed $170 million across 77 projects. Table 1 provides basic data on PWCB's governance program in this period.

| 2008-2009 | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011 | 2011-2012 | Total (cumulative) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data provided by Chief Financial Officer Branch, as of 2012-06-20 | |||||

| # of projects | 36 | 53 | 49 | 50 | 77 |

| Disbursements | $ 38,833,801 | $ 42,130,303 | $ 41,867,113 | $ 47,761,667 | $ 170,592,884 |

| Mean | $ 1,078,717 | $ 794,911 | $ 854,431 | $ 955,233 | $ 2,215,492 |

| Median | $ 517,283 | $ 400,000 | $ 600,000 | $ 446,621 | $ 1,200,000 |

Annual program spending ranged from a low of $38.8 million in 2008-2009 to a high of $47.8 million in 2011-2012. Overall, there were 77 projects during the period, although at any given time, the number of operational projects was in the range of 40-50. The average spending per project is quite high, nearly a million dollars in most years. However, a few large projects with large disbursements skew the averages considerably. A better indication of the typical project size is represented by the median figures, which gives the midpoint at which half the projects have higher disbursements and half the projects have lower disbursements. Most partners received total funding of less than $5 million with just a few agencies exceeding that figure. In total, 20 executing agencies account for approximately 82% of the total expenditures by the governance program and 45% of the number of projects.

2.2.2 Geographic Distribution

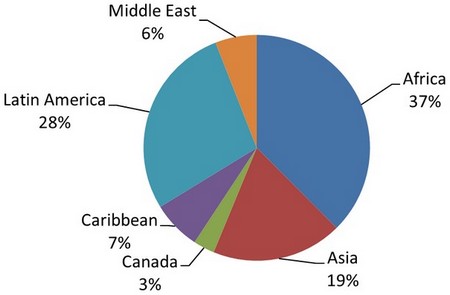

The governance program includes projects in 81 countries, in every region of the world. Figure 1 displays the geographic distribution of the projects.

Figure 1: Geographic Distribution of Governance Projects (percentage)

Data provided by Chief Financial Officer Branch, as of 2012-06-20

Over a third (37%) of the governance projects were in Africa, while just under a third (28%) were carried out in Latin America. Programming in Asia accounts for 19% of the portfolio, with smaller percentages allocated to projects in the Caribbean (7%), the Middle East (6%) and Canada (3%). Many countries have just one or two projects, although a few countries have a small concentration of governance projects (three to five), such as Tanzania and Bolivia .

2.2.3 Governance Program Focus

PWCB's governance program is focused around the 2006 Democratic Governance Statement, which states:

Democratic governance is essential for poverty reduction and long-term sustainable development. CIDA's work in this area aims to make states more effective in tackling poverty by enhancing the degree to which all people, particularly the poor and the marginalized, can influence policy and improve their livelihoods.Footnote 6

3.0 Findings - Development Results

3.1 Relevance

3.1.1. PWCB governance projects are responding to locally identified needs and priorities

In almost all sampled projects (93%), program activities respond well to locally identified needs and priorities through active participation of local partners from design to implementation. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities demonstrates this high degree of relevance in its successful approach:

The design of our PWCB programming is demand-driven, with our local partners involved from the very start in defining local needs, priorities and requirements, and our national level coordinating partners ensuring this is aligned with national level poverty reduction strategies… We work with our partners to select local interventions that can help model implementation approaches, provide good governance models and get other planned results such as those related to sustainable economic growth.Footnote 7

Many respondents highlighted that Canada needs to be relevant and responsive to local needs. Program planning must be a joint effort between local and Canadian partners based on a shared strategic vision that encourages creative approaches. Thus, local and Canadian partners should use a systemic approach to support development in their sector, thematic area and/or location in a country or region. The evidence indicates that projects have a higher likelihood of effecting change in local governance structures and systems when creating or seeking alignment between the beliefs and vision of community organizations and the objectives and plans of local and/or regional governments. For example, in the Tanzania case study (Appendix E), the Executive Director of a local partner (working with CIDA's partner Oxfam ) and the local District Commissioner held a joint event where young people participated in role-playing exercise on gender based violence before an audience of more than 100 people. Many levels of partnership were involved and worked together to realize the event, including beneficiaries, a local Tanzanian community organization, local government officials, and the Canadian partner.

Projects in areas such as election monitoring were also highly relevant to local needs and priorities. With respect to the monitoring of the election in Haiti, the evaluation of that project concluded:

There is absolutely no doubt in the minds of most of the stakeholders met with or interviewed, or those who completed the questionnaire, that the JEOM [Joint Electoral Observation Mission] in Haiti was highly relevant. This sentiment cut across various stakeholder categories, to include Haitian government and non-government organizations, multilateral and bilateral organizations, and representatives and observers from 10 different countries. The presence of the OAS, that of the CARICOM, and the support of the international community, including the MINUSTAH [United Nations Mission for Stabilization in Haiti], made the elections a success.Footnote 8

3.1.2. Most projects have local ownership and align with government priorities

In terms of aid effectiveness principles, such as those reflected in the Paris Declaration, the evaluation evidence indicates that most local partners do take ownership of projects. For example, a local Oxfam partner in Tanzania is working with local government officials, ensuring that the project aligns with government plans (Appendix E).

The Inter Pares program demonstrates alignment between Canadian and local partners, according to aid effectiveness principles. Inter Pares ' approach was described as follows:

Inter Pares ' approach to strategic thinking and program design, based on reciprocal learning between Northern and Southern organizations, exemplifies the spirit of inclusive and effective partnerships, highlighted in policy statements such as CIDA's Strengthening Aid Effectiveness and the Accra Agenda. Inter Pares ' practice of accompaniment with its principal Latin American counterpart echoes its program design in Africa: a readiness to align its own contribution to the priorities of its counterparts, while joining them in strategic thinking about organizational and program directions. This approach exemplifies key principles in the aid effectiveness agenda: strong partnerships, southern leadership and ownership, program-based funding, co-ordination.Footnote 9

3.1.3. Most Canadian organizations effectively consult with their developing country partners

The evaluation evidence indicates that, in most cases, local partners agree that they have been well consulted and involved throughout proposal development and project implementation. The importance of consultation cannot be overstated. For example, the Canadian Urban Institute Project evaluation stated:

Program and project activities . . . were designed in complete collaboration with partner organizations and appropriately reflected their needs and contextual environment. Program design was found to be entirely collaborative with partner organizations having a high level of input . . . . The results generated . . . were extremely relevant. Every partner organization interviewed by this Evaluation commented that their mutually positive and respectful relationships . . . were the primary reason for success . . . This was a credit to the ability of Canadian Urban Institute and its personnel to cultivate and foster a constructive rapport for program work which . . . is a key indicator of success.Footnote 10

This type of partnership requires trusting cross-cultural relationships. All lines of evidence indicate that nurturing these relationships requires significant time. Time was frequently cited as very important to building successful partnerships in which all parties are fully engaged in achieving long-term goals.

Most of PWCB's Canadian partners have a long history of working with their local partners. Project planning typically involves both Canadian and local partners throughout all stages of the proposal process. However, there were a few examples, especially in newer partnership arrangements, where local partners were not involved early in the design phase or continuously throughout implementation. This often resulted in these projects not completing activities that the local partners did not support (for example, in gender awareness) and/or not providing support to external missions. In these examples, attempts by the Canadian partner to engage in consultation with the local partner often started later in the process and in some cases were token in nature.

Local partners must be fully engaged in the planning process. Without this engagement, they are unlikely to see the relevance of a project. This is instructive since, without full buy-in, local partners are unlikely to carry out the activities intended to produce relevant results. Similarly, local partners know about the legal and administrative frameworks, impediments, and capacity constraints that are key to achieving governance results in their context. Involving local partners fully in the needs assessment, strategy and proposal writing from the outset is essential to identifying risks and corresponding mitigation strategies.

Key Findings - Relevance

- Nearly all sampled projects demonstrate good relevance to locally identified governance issues.

- Where local partners have been fully involved from the earliest point in the project planning process, there is higher likelihood of successful implementation.

- Successful projects feature mutually respectful relationships in which Canadian and local partners openly discuss strategic concerns regarding the relevance of programming.

3.2 Effectiveness

PWCB's partnership approach relies on Canadian and local partner organizations to achieve governance results. The program's effectiveness was assessed according to the four elements of democratic governance: Accountable Public Institutions, Freedom and Democracy, Human Rights and Rule of Law. Effectiveness is also considered in relation to the achievement of planned outcomes demonstrated by different models of partnership and the unique contributions made by non-governmental organizations in the area of governance.

3.2.1. PWCB partners are helping to build accountable public institutions

Program activities in the area of Accountable Public Institutions is oriented towards five desired outcomes: 1) enhanced transparency and anti-corruption, 2) financial and economic management, 3) improved service delivery, 4) policy coordination, and 5) strengthened audit, statistical capacity and human resource management. These five areas are reviewed below.

The first expected outcome is enhanced transparency and anti-corruption. Transparency International was successful in its anti-corruption work, specifically in building the capacity of national chapters. In addition, the Network for Integrity in Reconstruction successfully worked with community organizations to build local capacity in monitoring reconstruction projects and disseminating information about corruption.Footnote 11 Transparency was also an outcome realized by the Canadian Comprehensive Audit Foundation's Legislative Audit Assistance Program, which increased the number and quality of value-for-money audits performed by participating Supreme Audit Institutions and improved capacity to conduct the four phases of performance audits.Footnote 12 Improvement in the quality of performance audits by the local partner National Audit Office of Tanzania was also highlighted by the Swedish National Audit Office naming Tanzania's 2010 audit on maternal health as "one of the two best performance audits in the region."Footnote 13

Several Canadian partners conducted programs designed to improve financial and economic management. Once again, project evaluations noted that several projects reported outcome achievements in this area. The final evaluation of the Canadian Urban Institute Partnership program noted that:

There are projects within the IUPP [International Urban Partnership Program] that may easily be seen as having a direct measurable impact on poverty reduction. These, in the context of the Philippines, are the establishment, once again through Canadian Urban Institute support, of the tourist projects in Guisi and Salvacion. There, the evaluation was able to speak directly to community members who provided many examples as to how the projects had directly raised the economic level of individuals (and the larger community) by providing them with new livelihood opportunities….[International Urban Partnership Program] activities leading to poverty reduction were easy to see.Footnote 14

Despite the generally positive results, several projects faced challenges to achieving outcomes. Explanations given include differences among partners and regions, limited possibilities for South-South synergy, and a lack of coherence and strategic focus on root causes of inequalities.

In promoting policy coordination, outcome achievements are less notable. While most projects have documented their activities, there is little evidence of specific outcome level results. No examples were identified in the project evaluation reports. In the interviews in Tanzania, the policy success of Sustainable Cities International in getting the program "Urban Agriculture" in Dar es Salaam approved by municipal government authorities is noteworthy and has resulted in the start-up of actual urban agriculture projects. However, this success appears to be an isolated example.

Expected outcomes for strengthening audit, statistical capacity and human resource management have suffered due to partners' lack of political or management will and/or insufficient human resource capacity to support audits and statistical analysis. Other constraining issues include inefficient human resource management practices, human resource gaps in management and technical capacity in these specific skill areas, and lack of core funding or sufficient funding to motivate staff and pay for programs. Notwithstanding these challenges, projects have achieved some limited outcomes in building capacity of auditors (Canadian Comprehensive Audit Foundation), supporting audit of election and tabulation of results (OAS), tracking urban indicators and statistics (Canadian Urban Institute), and improving local capacity in strengthening civil society and peace building (Alternatives).

Overall, these examples highlight tangible achievements in building accountable public institutions by CIDA's Canadian partners and their local partners around the world, some of which have already achieved outcome-level results, and some requiring additional time to achieve outcome-level results.

3.2.2. Outcomes are being achieved in building freedom and democracy

The second pillar of PWCB's governance program is support for Freedom and Democracy. Two outcome areas fall within this area, namely 1) building open and accountable political systems, and 2) promotion and use of public media.

The outcome area of building open and accountable political systems consists of support in a number of areas: electoral, legislative assistance, decentralization, federalism and local government, political parties and competition. More than 15 projects documented significant outcomes in progress reports and evaluations. These projects include:

- Canadian Comprehensive Audit Foundation (audit legislation);

- Institute of Public Administration of Canada - Mécanisme de Déploiements pour le Développement Démocratique (new policies, legal instruments, strengthened systems etc.);

- Centre for International Governance Innovation - Local Initiatives Support (building linkages between community organizations and governments);

- Federation of Canadian Municipalities (municipal government capacity building);

- Canadian Bar Association - Strengthening Access to Justice (legislation on juvenile justice);

- Canadian Urban Institute Partnerships Program (increased multi-stakeholder participation in local governance and capacity);

- Sustainable Cities (new collaborative governance model linking citizens and municipal decision makers);

- Inter-Parliamentary Union (use of toolkit by parliaments); and

- SalvAide (strengthened social organizations).

One notable project is the OAS Electoral Observation Mission in Haiti. The evaluation concluded that it "exceeded expectations" and "was effective and achieved the objective of contributing greatly to the integrity, impartiality, transparency and reliability of the electoral process."Footnote 15

For the second outcome of this area, creating a democratic environment focussed on the use of public media, outcomes were evident from Rights and Democracy, Inter Pares, CIVICUS, Alternatives, and Sustainable Cities. A particularly effective project in this area is the Journalists for Human Rights in Sierra Leone, which helped build a stronger and more independent local media that focused on good governance and human rights. The project trained more people than planned, including one third of the editors, media outlets and journalists in the country. As a result, media programs on good governance and human rights are now available to 85% of the people in Sierra Leone.

3.2.3. Some evidence of achievements in the area of human rights

Program activities in human rights includes two outcome areas: 1) protecting the rights of women, children and marginalized groups and 2) strengthening of formal human rights institutions and mechanisms.

In contrast to the above areas of governance, human rights program activities has achieved fewer significant outcome level successes. Challenges to producing outcomes in the area of rights of women, children and marginalized groups included a lack of rights-awareness among many of these groups. In addition, a marked lack of empowerment, combined with governments that do not support the establishment of human rights commissions, leaves the rights of women and children and/or migrant workers under constant threat. Thus, many projects have not yet achieved outcome-level results in this area. Indeed, project reports in this area narrate successful activities and outputs but, given the time it takes to achieve human rights outcomes, there were fewer tangible outcome achievements.

Despite this, several projects are moving towards outcome level achievements. For example, the evaluation of Alternatives emphasized that training activities achieved their immediate results (outputs), and the cumulative effect of these outputs generated increased awareness of human rights within the local communities (outcome). Similarly, the Centre for International Governance Innovation Local Initiatives Project reported contributing to a policy result, which segregated minor offenders (12-16 years old) from adult offenders, in line with the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. They achieved an agreement between government and civil society, a particular challenge in the area of human rights in Central Asia.

Similarly, progress is being made towards strengthening formal human rights institutions and mechanisms. Trust is critical in this area, given that civil society organizations lead these programs and formal human rights institutions are often government-supported organizations. Among projects intended to protect and promote human rights in general and/or the rights of women and children or migrant workers in particular, Co-Development Canada was particularly effective at policy level contributions to laws on equal opportunity. Their project also supported dramatically increasing numbers of labour mediation cases, and special initiatives were taken to integrate women into all activities.

Similarly, the Equitas program achieved good results from their annual human rights training program and their multileveled follow-up. This program and its alumni created a platform upon which long-term outcomes in human rights can be realized by civil society. The participative approach also has long-term benefits. Equitas' human rights training program has a strong reputation and receives three to four times the number of applicants that it can accept annually. It also provides networking opportunities for civil society leaders. Programs like this, which influence a wide array of civil society organizations, have a much larger influence than just the training. They introduce people to each other and help build international networks, which link the work of human rights organizations nationally, regionally and internationally.

3.2.4. Limited program activities in strengthening the rule of law

Two outcome areas are related to strengthening the rule of law: 1) advancing public legal education and engagement; and 2) promoting predictable, impartial, accessible, timely, and effective legal systems.

Very few projects were aimed at advancing public legal education and engagement. The two projects managed by the International Institute for Child Rights and Development (the "Child Protection Partnership" project in Thailand and Brazil and "Building National Child Protection" project in Colombia) are notable because they both achieved outcomes on improving public legal education and engagement, particularly with the police in all three countries. In these projects, over 50,000 children have been better protected from violence and exploitation through information and communication technologies. These projects demonstrate how numerous and varied stakeholders need to be involved in order to institutionalize gains that protect children from violence and exploitation. Challenges in these projects, and others in the area, include rapid turnover in police services and governments, the need to continuously engage new institutional leaders, and the longer timeframes needed to realize institutional change.

Promoting predictable, impartial, accessible, timely, and effective legal systems is the second outcome area. The final evaluation of the Canadian Bar Association's "Strengthening Access to Justice" project concluded that the project "has made a significant contribution by injecting resources and guidance into support for collaborative activities. In terms of the indicators provided, and in a broader sense, there is little doubt that this result is being achieved."Footnote 16 The evaluation report also concluded that the project facilitated access to justice by "bringing together a range of stakeholders with often competing agendas and interests. The results achieved in two years are a very creditable return on the investment of resources and imagination."Footnote 17 This finding was evident in Tanzania, where one of the stakeholders reflected:

Accountability, volunteering and openness are the words that come to mind. The most significant achievement was watching the transformation of end-beneficiaries who took on advocacy for the change in law, promotion of legal aid, participation in training and advocacy for change in their communities. They seemed to have moved from victims to survivors.Footnote 18

The evaluation concluded that it was not easy to achieve tangible outcomes in projects like this because of challenges such as institutional rivalries and an absence of a culture of cooperation. In addition, a lack of support from the legal system, and frequent personnel turnover at every level of many country systems, also impedes progress.

The present evaluation found no other evidence of significant outcomes to support informal legal practices that respect human rights and support independent and non-discriminatory judicial systems. Projects that focussed on alternative dispute resolution and transitional justice were not evident in the sample of projects. This gap should be addressed in future governance program activities.

3.2.5. Outcome achievements demonstrated by different models of partnership

In addition to the four elements of democratic governance, effectiveness was also considered according to different models of partnership.

Non-governmental organizations are effective catalysts for social change when the partnerships are deep, and the partners are working together to achieve mutually agreed outcomes. A representative comment from one CIDA interviewee was that "Models that bring North-South, South-South and grassroots together in partnerships to work with and/or influence governments are best."Footnote 19 This was echoed by Tanzanian stakeholders working on all six governance projects reviewed by the evaluation. Specifically, four of those projects work with small local organizations that carry out activities and/or demonstration projects representing varying partnership models (such as service delivery, self-help, etc.).Footnote 20 In terms of effectiveness, the organizations that achieve their targeted outcomes are usually those that have a specific focus (i.e. municipal governance) and involve a large number of diverse stakeholders from the grassroots to political level.

In the sample of 42 projects, many focus on working with local non-governmental organizations at the municipal or community level of governance and some focus on more traditional governance projects that link Canadian sector expert technical assistance with parallel organizations in partner countries . These projects are different and work to build national and/or regional capacity across the four elements of Democratic Governance. As described in the next section, some projects are linked at many levels, which is ideal in governance program activities.

3.2.6. Non-governmental organizations make unique contributions in the area of governance

This section considers the unique contributions of non-governmental organizations to effective governance programming. Many Canadian non-governmental organizations provide unique value by assisting local counterparts to develop their capacity to address local governance issues. PWCB officers emphasized that local non-governmental organizations are close to the ground and know the cultural context and governance reality. Understanding the needs in their community allows local organizations to cut across many layers of society and get more people involved. While benefitting from assistance from the Canadian partner, the local partners are most able to produce the real changes on the ground.

For example, the Association for the Development of El Salvador, which has been a local partner for over 25 years, demonstrates the special value of non-governmental organizations. It was created to address the post-conflict challenges of resettling displaced residents returning to rebuild their communities and cultivate their lands. Building on local understanding of their communities, the Association evolved into a strong leader in social justice and democracy promotion, corroborated by its Canadian partner SalvAide. One outcome was the creation of multi-stakeholder assemblies in municipalities, which included women, youth, and other marginalized voices.

Another unique example is the approach used by the Sustainable Cities project in which facilitators worked with municipal leaders, municipal officials, community leaders, local organizations, etc. The project's demonstration projects employ people and address tangible issues such as waste management and urban agriculture that could be both scaled up and replicated.

Key Findings - Effectiveness

- Overall, the governance portfolio of PWCB projects is concentrated at the community and local government levels.

- Most successful outcomes support the work of local partners and specific beneficiaries. Relatively few outcomes are targeted or achieved at the national government level.

- Outcomes have been achieved in the areas of Accountable Public Institutions and Freedom and Democracy, with particular successes in the latter. There are mixed results in the area of Human Rights, and limited programming in the Rule of Law.

- Successful models involve strong partnership relationships with mutually agreed outcomes, and focus on a specific area (i.e. municipal government), with diverse stakeholder involvement. Canadian non-governmental organizations are able to act as catalysts linking different levels of government. Local partners have valuable local knowledge, particularly of governance realities, which enables them to implement interventions geared for success.

3.3 Sustainability

In this evaluation, sustainability was assessed by taking into account 1) the degree of local ownership and accountability, and 2) the likelihood of ongoing benefits even as donor funding winds down.

3.3.1. Local ownership improves sustainability

The 2008 Review of Governance Programming in CIDA found that governance programming in the Agency did not demonstrate extensive local ownership. The report noted that "the voice of the host governments or agencies to be weak" and concluded that there was "little evidence of host governments initiating a project or program and playing an active role in co-ordinating the efforts of CIDA and other agencies."Footnote 21

In recent years, international agreements have emphasized local ownership as a key development principle contributing to sustainability. Specifically, the Accra Agenda for Action (AAA) broadened the Paris Declaration principles to include engagement with parliament, political parties, local authorities, the media, academia, social partners and broader civil society. The importance of local ownership was also emphasized at the 4th High Level Forum in Busan, South Korea in 2012.

Thus, CIDA has been challenged, both by prior evaluations and by international standards, to increase local ownership in its governance program. Assessment of voluntary sector funding proposals does include consideration of plans for shared accountability for results, as well as clear identification of respective roles and responsibilities.

This evaluation found that PWCB's Canadian partners have developed long-term partnerships with host country organisations that demonstrate a high degree of mutual respect and collaborative work from initial project design throughout project implementation. Table 2 highlights some selected examples of partners' demonstration of local ownership, as gleaned from evaluation reports, project documentation and interview notes:

| Canadian partner organization | Evidence of Local Ownership |

|---|---|

| Alternatives | The evaluation report concluded: "The project is sustainable as it strengthens Community Development Centers to carry out their activities."Footnote 22 |

| Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace | The evaluation report concluded, "Participants are confident and committed that the organizations will maintain and continue with the program beyond the end of CIDA's program involvement. Most of the stakeholders think that they have, or will find, alternative sources of financing, but most importantly there is a commitment from the communities and the NGO [non-governmental organization] to push ahead with an extension of activities related to those of CIDA's program."Footnote 23 |

| Canadian Comprehensive Audit Foundation | The evaluation report concluded that Supreme Audit Institutions "display high levels of local ownership."Footnote 24 |

| Equitas | The project established formal alumni organizations in several countries linked with community organizations to push for sustainability of human rights education activities worldwide and support for dynamic community organization networks. |

| Journalists for Human Rights | The "train-the-trainer" design, working with selected local journalists and intensely mentoring them for five months, prepared them to act as resources to local media after the project ended. |

| Network for Integrity in Reconstruction | The "inclusion of local officials and village level dignitaries in monitoring projects that have an impact on their lives builds ownership that reconstructing governments use in later project conceptualization."Footnote 25 |

| Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs | The "train-the-trainer" design used an on-going systematic program approach to gain greater reach and sustainability. |

The examples above demonstrate the critical role of learning in generating local ownership and sustainability. Developing capacity within local organizations embeds the project benefits within partner institutions, increasing the likelihood that project benefits will continue after funding winds down. In many projects, activities contributed towards increased capacity and ownership of stakeholders, as noted in narrative reports, evaluations, interviews, and observations in Tanzania.

3.3.2. Sustainability is a challenge in many projects

Despite these examples of local ownership, sustainability is a challenge in many projects. This evaluation identified several common challenges associated with sustainability, including national governments' sometimes-tenuous relationships with civil society, which can make them less receptive to working with community organizations; and the lack of project exit plans.

Including extra time at the end of projects to draft and implement an exit plan would contribute to improved sustainability of benefits from CIDA's investments. In 2009, a workshop hosted by PWCB discussed challenges to sustainability.Footnote 26 The workshop also highlighted the need for each project to develop an appropriate exit strategy. Workshop participants noted that many Canadian partners have been very effective at building long-term relationships with partner organizations. However, Canadian partners are not adept in designing exit strategies with their local partners for project termination. With few exceptions, content analysis of the evaluation reports and file documentation supports this observation. This is further supported by observations in the Tanzania Case Study (Appendix E).

As noted in the 2008 Review of Governance Programming in CIDA, most sampled projects lack adequate information about sustainability.Footnote 27 Little seems to have improved in the intervening years. Evidence reviewed for the present evaluation indicates scant availability of detailed sustainability or exit plans that outline how long term governance outcomes will be sustained.

Given the challenge of not knowing what will happen in the future, few projects specifically reported on the likelihood of local ownership leading to continued benefits. One PWCB interviewee summarized the difficult reality of ensuring ongoing benefits as follows: "It is unclear whether any or all of these initiatives could continue without further funding, but many of the ideas they have introduced will remain and be developed."Footnote 28 Many Canadian partner organisations understand that overall project benefits can have long-lasting impact on results when sustainability strategies are employed. For example, one Canadian partner stated:

We can never be certain that the results and benefits will continue but we are sure that most are likely to continue. How have we achieved this? We use the following methods to promote sustainability of results: a) By building local capacity of both municipal partners and community and private sector partners, so that they have skills in both management and resource leveraging into the future, b) Our beneficiaries are in the driver's seat from the start, meaning that we don't implement the projects for them...rather we help them to implement their own projects. When partners own the projects, they tend to continue after Canadian engagement has ended. c) We codify our processes and methods through guidebooks, toolkits and other manuals, that help organizations to survive changes in personnel over time, d) We build leadership capacity among elected officials and private sector and community leaders, providing ongoing stewardship into the future, and e) We strengthen the capacity of communities to get engaged in local governance processes and to become partners with municipal and regional governments, allowing non-state actors to continue keeping their governments accountable and to sustain developmental gains after the Canadian Urban Institute has exited.Footnote 29

Key Findings - Sustainability

- Projects with demonstrated local ownership are more likely to be sustainable.

- Capacity building embeds the project benefits within partner institutions, increasing the likelihood that they will continue

- As noted in 2008, most governance projects lack adequate information on sustainability.

- Many Canadian partners are very effective in building long-term relationships with partner organizations, but are less effective in working with local partner organizations to design an exit strategy for after CIDA funding winds down.

3.4 Gender Equality

CIDA's Gender Equality Policy aims to support the achievement of equality between women and men to ensure sustainable development. The three objectives of the policy are: 1) to advance women's equal participation with men as decision makers in shaping sustainable development of their societies; 2) to support women and girls in the realization of their full human rights; and 3) to reduce gender inequalities in access to and control over the resources and benefits of development.

3.4.1. Most projects did not integrate gender equality into program planning and management

CIDA has developed gender sensitive planning tools and techniques which are intended to empower women as participants and beneficiaries of its development investments. Like all other CIDA programs, the PWCB governance program is expected to comply with the Agency's Gender Equality Policy. PWCB is also expected to encourage Canadian partners to incorporate gender analysis in project planning and management and to pursue gender equality outcomes. In order to guide the planning and implementation of a project, gender analysis should be carried out at the early stages of the project cycle and be integrated into the project itself.

At PWCB, many project proposals discussed gender, but in several cases, the organizations that developed such proposals were unable to achieve all their planned gender objectives. The mixed success in achieving planned gender objectives is partly attributable to partners not using gender tools to collect and report on gender outcomes. For projects in the present evaluation sample, 18 of 42 sampled projects (43%) fully reached all the project planning and management criteria of CIDA's Gender Equality Policy. Some have also established mechanisms and tools to advance strategic issues to achieve gender outcomes, (i.e. to afford access and control of resources to women). In addition, in several project design and implementation documents, reference is made to the equal inclusion of women and men in project activities. However, it is difficult to discern the extent of the involvement of women vs. men due to lack of sex-disaggregated data. For this reason, project reports should provide sex-disaggregated data. For example, the Canadian Urban Institute project provided sex-disaggregated data for all activities, including training and civil engagement workshops.

A need exists to better understand the role of gender in development. Including women in consultations is not sufficient to ensuring that gender specific issues are addressed in design, planning and implementation. In terms of analysis of cultural and other institutional barriers that could constrain achievement, consultation is very important. For example, a mid-term evaluation of a project in Africa noted that, in some parts of the country there had been a lack of activity on the project's gender component, while in another part gender-related activities had been more successfully delivered. The evaluation attributed this difference to the need for more negotiation and consultation with the local partners. In other words, the detailed project design needed to be adapted sufficiently to ensure wide understanding of the differing social and cultural context.

Beyond the effective use of gender tools to collect and report on data, based on triangulated evidence, a positive correlation emerged between the project's relevance to the local context and the achievement of gender equality outcomes. In other words, the absence of buy-in by a partner can have a negative effect on the achievement of gender outcomes. This is a reason why early and consistent involvement by local partners in project planning and management is so important with respect to achievement of gender equality outcomes.

This evaluation found no evidence that the majority of projects in the sample are allocating specific funds to gender equality. Few projects in this evaluation focused exclusively on gender, but several do have gender as a central theme. Gender-allocated spending in many other projects is either small or not recorded at all.

Several Canadian partners do have gender-specific policies, tools and checklists, but only a few have integrated all elements of CIDA's Gender Equality Policy fully into their organizations. The implementation of these tools and checklists is a critical stepping-stone to the achievement of gender equality, as they facilitate better collection and reporting on gender outcomes. Several project evaluations recommended that PWCB focus on education or training on gender analysis to increase results in diverse cultural settings. Clearly, projects that focus on gender are more likely to show disaggregated gender equality results. Nevertheless all projects need to use the gender lens in their work with their local partners and local country context.

3.4.2. Projects that report on gender outcomes demonstrate significant achievements in gender equality

This section presents examples of gender equality outcomes as they align with the three objectives of CIDA's Gender Equality Policy.

Advancing women's equal participation – Documents and evaluations identify several examples of women's participation in meaningful decision-making through, for example, leadership training for empowerment or increased participation of women in decision-making. For example, in the Tanzania Case Study (Appendix E), Sustainable Cities included several sub projects with women leaders in urban farming and planning. Similarly, the Tanzania Case Study also raised examples of increased decision-making by women in community and private households, for example, decisions about expenditures and other resources.

The Inter Pares program focused on women's political participation at the municipal level and intended to provide women leaders with skills to participate effectively in local, national and regional settings. This model has been replicated and adopted by several Central American women's organizations. In Canada, the Institute for Management and Community Development at Concordia University facilitated the participation of low-income and marginalized women and men in which 1,000 individuals participate every year. This project has created learning networks of participants both in Canada and in the South.

Supporting women and girls in realising their full human rights – Human rights encompass interdependent and overlapping experiences (for example, of being female, indigenous, poor and uneducated, etc.). The Inter Pares Program dealt well with this. For example, the Tri-People's Concern for Peace, Progress and Development in Mindanao worked closely with a cohort of women and girls who faced multiple vulnerabilities and challenges to their rights. Specifically, the project carried out training with indigenous women in rural areas and encouraged their participation in community activities. This is also a good example of why human rights are critical in gender analysis, since not all women and girls (even from the same society) have to contend with the same degree of vulnerability or face identical barriers.

Reducing gender inequalities in access to resources and benefits – Significant outcomes were also found in reducing gendered economic equality, such as increased economic options for poor and marginalized women, access of women to sustainable development, and increased awareness of the benefits of social, economic and political empowerment for women.

An example of a project that addressed gender is the large Deployment for Development project, led by the Institute of Public Administration of Canada, which effectively used gender tools to collect and report on data. Triangulated evidence demonstrated a positive correlation between gender equality outcomes and the project's relevance to the local context and local needs. Similarly, in Kenya, the project influenced the public service reform process to take corrective action to provide increased access for Kenyan women to basic services, in order to enhance women's opportunities for political participation and help lift them out of poverty.

Key Findings - Gender Equality

- Most projects worked towards achievement of gender equality outcomes but only some fully used gender analysis tools, integrated gender into their policy framework and systematically reported on gender results. (Note that gender equality tools are shared in the calls for proposals process.)

- Projects that integrated gender fully in planning and management reported significant achievements in gender equality for all three objectives of CIDA's Gender Equality Policy.

- Beyond the effective use of gender tools to collect and report on data, evidence demonstrates that there is a positive correlation between a project's relevance to the local context/needs and the achievement of gender equality outcomes.

3.5 Environmental Sustainability

3.5.1. Few projects required environmental assessments

Compliance with the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act has been a requirement for PWCB governance projects since at least 2007.Footnote 30 The CIDA Environment Handbook for Community Development Initiatives (2005) provided Canadian partners with extensive guidance on policy and regulatory context, planning and implementation procedures and use of environmental assessment tools. Canadian partner proposals were assessed by CIDA Environment Specialists for the integration of environmental considerations.

Content analysis of the file documentation for projects in the sample revealed that all Funding Approval Memos contained an "Environmental Assessment" section, which summarised whether proposed initiatives complied with federal requirements under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act.Footnote 31 Approval memos also noted whether additional environmental assessments had to be carried out during the planning stages and/or at the sub-project level. In several cases, these additional requirements were stipulated in the Contribution Agreements with Canadian partner organizations.

Canadian partner organizations were required to "systematically integrate environmental factors into their decision making processes, in line with CIDA's Policy for Environmental Sustainability"Footnote 32 and prepare an Environmental Assessment, which included a description of environmental issues in their project, and an analysis of possible detrimental environmental effects and proposed mitigation measures.

Most of the projects in the sample did not focus on environmental issues and did not require Environmental Assessments. Content analysis of past evaluation reports, file documentation and interviews with Canadian partners, Tanzanian partners and CIDA officers revealed little or made no mention of environmental issues unless it was an explicit focus of the project.

3.5.2. Both success and challenges in addressing environmental issues

One of the few cases where an Environmental Assessment was required involved the Canadian Urban Institute project that included in its proposal detailed potential environmental impacts and mitigation measures for their overall plan. The annual work plan included strategic environmental assessments for each demonstration project in target countries. The Canadian Urban Institute assisted each local partner in understanding the possible negative environmental consequences of their sub-projects and mitigation strategies to overcome them.

Other projects focussed on municipal governance serve as good examples of how environment considerations can be effectively integrated within governance projects. For example, Sustainable Cities addresses the environment in half of the demonstration projects in three cities, and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities integrates environment in its demonstration projects. The Horizons of Friendship Program also developed an environmental policy with its partners to serve as a guide to improve their work together. They also produced an Environmental Management Plan, which required partners to analyze their projects using a questionnaire based on Canadian guidelines. The plan included training, capacity building, and activities such as reforestation, community sanitation campaigns, and promotion of agro-ecological practices.

A few sampled projects encountered challenges with respect to whether they needed to complete an environmental assessment for some of their sub-projects. Content analysis of past evaluation reports revealed that in some cases, compliance issues were raised long after projects had begun and required CIDA Environment Specialists to intervene and provide coaching and training. In those specific projects, Canadian partners' lacked capacity to conduct environmental assessments and points to the need for those projects to provide training for their sub-project partners.

Key Findings - Environmental Sustainability

- Most projects did not require an environmental assessment as they did not focus on environmental issues or anticipate environmental impacts.

- For those projects that did have anticipated environmental impacts, Canadian partners prepared very complete Environmental Assessments.

- A few Canadian partners need to build capacity in environmental assessment.

4.0 Findings - Management Factors

4.1 Coherence

4.1.1. PWCB partners have minimal coordination with other CIDA-funded projects

Coordination and harmonisation of donor activities, including those of the implementing organisations, is a well-accepted principle for aid effectiveness.Footnote 33 This principle was also reinforced in the Accra Agenda for Action with the intention to "reduce the costly fragmentation of aid."Footnote 34

Geographic analysis of the PWCB governance program revealed that the 77 funded projects collectively undertook activities in 81 identified countries, of which 18 hosted between five to nine sub-project governance activities. An additional seven countries hosted ten or more sub-project governance activities: El Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Colombia, Philippines, Tanzania and Ghana. Based on this geographic analysis, opportunities for coordination and harmonization of governance project activities existed in these countries.

Content analysis of past evaluation reports and project file documentation revealed few documented examples of coordination and harmonisation between PWCB governance projects and/or with other donor projects in the same country. Understandably, most projects focus on achieving their own outcomes and working with their host country partner, government officials and/or other civil society organisations involved in their project.

Despite this, some examples of coordination were identified. For example, interview data from Canadian partners working in Tanzania (Appendix E) demonstrates an emphasis on building more inclusive partnerships and networks of local partners at the local level. A good example of building such inclusive partnerships is being carried out by Sustainable Cities International in three cities in Africa (Dakar, Dar es Salaam and Durban). This multi-stakeholder project engages with, and coordinates across, all levels of government, especially with municipal leaders with whom they link grassroots beneficiaries carrying out demonstration projects on waste management, urban agriculture/food security, and urban planning.

Examples of coordination and harmonization were also found at the regional level. A good illustration was the initiative taken by the Canadian Comprehensive Audit Foundation to improve donor coordination by joining with 15 donors in forming "a coordinating body (International Organization of Supreme Audit)" to address issues of governance and accountability.Footnote 35

Despite these examples, coordination was minimal with other CIDA-funded projects. For some small countries with several unrelated PWCB-funded governance projects, the implication is aid fragmentation. Implementation of the Paris Declaration has been characterized as mostly slow with regard to "Less duplication of efforts and rationalized more cost effective donor activities."Footnote 36 The Paris Declaration evaluation found that aid fragmentation was still high in at least half of the 21 countries that took part in the evaluation.Footnote 37

4.1.2. An opportunity exists for PWCB to further facilitate partners' coordination efforts

With respect to responsive program activities, the 2008 Review of Governance Programming in CIDA observed that CIDA often takes a "hands-off approach" in relating to such investments. The report noted:

It is understood that, in responsive mode, CIDA cannot instruct a partner organization on how to design its project. It can however, give clear initial indications on its broad objectives, and, in considering an initial proposal, make detailed comments on areas for improvement that it wishes to bring to the attention of its partner.Footnote 38

File documentation was reviewed for this evaluation, particularly funding approval memos and decision records from CIDA's Program Review Committee. These documents indicate that proposals benefit from a broad internal consultation process within CIDA, including sector specialists, country program desks and missions, as well as an external review by other government departments and sometimes other donors. Observations, concerns and suggestions for improvement are fed back to proposal proponents. Interviewees also indicated that PWCB is willing to assist Canadian partners with proposal preparation and other technical assistance when requested.