Archived information

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Pakistan Country Program Evaluation 2007-2008 to 2011-2012

2014

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

The Development Evaluation Division would like to thank the consultant team of RBMG, Werner Meier, Michael Miner, Zulfiquar Jaffer, Syeda Viquar-un-Nisa Hashmi and Parthasarathi Gangopadhyay for the planning and execution of the data gathering and analysis phases of this evaluation..

To those individuals who graciously made themselves available for interviews in Canada and in Pakistan despite pressures and sometimes limited advance notice, a most grateful thanks. All provided valuable input and helped to ensure that the mission schedule unfolded according to plan. We would like to particularly acknowledge the excellent support and contributions from the Program team in Gatineau and in Islamabad.

From the Evaluation Division Muhammad Akber Hussain and Denis Marcheterre played key roles in managing the evaluation and drafting the synthesis report.

James Melanson

Head of Development Evaluation

Executive SummaryFootnote i

Evaluation Objectives

This evaluation aims to assess the results and management performance of the Pakistan bilateral program over the five-year period from 2007-2008 to 2011-2012. Data was gathered in mid-2013, from a representative sample of projects and related activities, and recommendations are provided based on this evidence.

Country Context and CIDA Program

Pakistan is a country of over 180 million people making it the world’s sixth most populous nation. With a population growth rate of approximately 1.6% it is expected to reach 230 million by 2030. Over the past decade it has faced enormous development challenges including the spill-over effects of the war in Afghanistan, internal violence and extremism, frequent natural disasters (floods, earthquakes), high levels of household food insecurity, and political instability featuring shifts between military and democratic regimes, making it a difficult environment in which to deliver development assistance.

With more than 40 million people living on less than $1.25 per day there are daunting development challenges in Pakistan. Adding to them is the perceived culture of entitlement and corruption at different levels of government. The decentralisation of powers to the provinces with deficient controls on procurement and public financial management has complicated this problem. Strong leadership will be necessary to establish the desired level of probity and accountability in public life. As with cooperation programs in some other parts of the world, the fiduciary risks for donors in Pakistan require active management. One measure has been to not use government financial systems in program implementation.

Between 2007-2008 and 2011-2012, the CIDA bilateral program disbursed $153 million on 44 projects in governance, health, education and women’s economic empowerment. Annual program spending ranged from a high of $35.9 million in fiscal year 2007-2008 at the beginning of the period to $27.5 million at the end of the period in fiscal year 2011-2012. The number of operational projects has seen a steady decline from 37 in 2007-2008, to 18 in 2011-2012.

Evaluation Conclusions

The evaluation drew the following conclusions:

The Pakistani context in which the bilateral program operated during the timeframe of the evaluation was unstable, complex and insecure. The Pakistan federal government’s devolution of powers to the provinces, weak coordination with donors, natural disasters and violent extremism made development programming particularly challenging. Despite the challenging development and operational context, the program achieved important outcomes through well-targeted and well managed project investments, and sustained policy dialogue activities. Partnerships with public, private and community-based entities were innovative (in particular Women’s Economic Empowerment) and contributed to the achievement of development outcomes.

The 2009 Country Strategy and 2009-2014 Country Development Programming Framework (CDPF) were intended to provide the formal framework to guide project planning over the review period. They recognized the importance of Pakistan to regional peace and stability, including in Afghanistan, and noted the need to bring stability to border areas. The relocation of the bilateral program to form the Afghanistan Pakistan Task Force was a management step consistent with a strategy to strengthen the border areas to fight extremism in support of Pakistan’s critical role in the region.

However, the pace of project approval and implementation that materialised over the review period, a time when operational complexity and risks were high, was not at the level originally envisaged in the planning documents, resulting in a relatively high ratio of planning effort to actual aid expenditure. Programming in a fragile context requires stability in priorities and flexibility in mechanisms, in addition to a vision shared and understood at corporate and program levels, conditions not completely attained on the Pakistan program over the review period.

The 2009 Country Strategy and the 2009-2014 CDPF were finalized prior to a succession of natural disasters, and the intensification of violent extremism resulting in large numbers of internally displaced persons. There were good examples of how the bilateral program was able to adapt its investments to natural disaster-induced priorities in a timely manner. Nonetheless, the program would have benefitted from greater attention to, and investment in, the transition to recovery, development, and longer-term resilience. As observed in the IHA evaluation of 2012, there is a lack of corporate emphasis on these issues, with limited recognition of them in country programming frameworks.

Projects’ effectiveness, relevance, coherence, and efficiency were satisfactory, as were aid effectiveness practices. Achieving sustainable results was challenging for most projects given the weak institutional capacities of most government structures in the country. The sustainability of results for all but a handful of projects would be in jeopardy were it not for follow-on donor funding. Performance management of projects is generally satisfactory, but risk management should improve, given the fact that the program operates in a fragile context. A renewed country strategy should provide clarity on future directions.

Evaluation Recommendations

Program planning:

Achieving sustainable results in the Pakistan context will require continuity of engagement, clarity of strategic objectives, and reasonable predictability of future expenditure. A renewed country program plan should establish these conditions. Planning and implementation capacity will need to correspond to the chosen level of objectives and expenditure.

Natural disaster preparedness:

Given the history of natural disasters in Pakistan, future program design should:

- to the extent possible provide for programming flexibility for meaningful response to future occurrences;

- take due account of the need to predict and manage risk, and build resilience; and

- anticipate approaches and mechanisms for working jointly with DFATD’s humanitarian programmers to facilitate relief – recovery – development integration.

Opportunities to learn and improve practices in the integration of relief and development programming should be pursued through activities such as after-action reviews for humanitarian responses (addressing processes as well as impact issues), participation in multi-donor or inter-agency evaluations, and lessons learned reporting.

Performance management:

In the future program planning process, a renewed performance management framework, with risk assessment, realistic indicators, and a monitoring strategy should be put in place. It should take full advantage of the flow of information from investment level performance reporting.

Institutional capacity:

Sustainability of outcomes depends not just on continuity of donor engagement, but on adequate enabling environments and institutional capacity in Pakistan. These factors should be explicitly addressed in investment plans, and in particular due attention paid to the capacity development of local partners that will be required to sustain outcomes after donor funding is no longer available.

1.0 Evaluation Process

This evaluation aims to assess the results and management performance of the Pakistan bilateral program over the five-year period from 2007-2008 to 2011-2012. Data was gathered in mid-2013, from a representative sample of projects and related policy dialogue, and recommendations are provided based on this evidence.

1.1 Evaluation Objectives and Methodology

The evaluation has three objectives:

- Take stock of the results achieved by the Pakistan program from disbursements made through the Geographic Programs Branch over the five-year period starting from 2007-2008 and ending 2011-2012; corresponding as much as possible to the objectives and expected results articulated in the 2001-2006 Country Development Programming Framework (CDPF), the 2009 Country Strategy and 2009-2014 CDPF;

- Assess the Pakistan bilateral program’s overall performance in achieving these results; and,

- Document and disseminate findings and formulate recommendations to improve the performance of the current or future Country Strategy and/or CDPF.

The following criteria were used:

- Effectiveness.

- Relevance.

- Sustainability of the results achieved.

- Coherence.

- Efficiency.

- Performance management.

- Cross-cutting themes.

- Aid effectiveness principles.

Findings and recommendations are based on 76 interviews done in Canada and Pakistan with Department staff and managers, partners in the field, donors, and beneficiaries; and 683 program and project related documents. In addition, a sample of 17 projects was visited in the field, covering 67% of total program disbursements ($152,980,004).

A review of the available files and reference documents was conducted to develop a sampling framework, and a purposive sample of projects from the overall portfolio was drawn with the following characteristics:

- Only bilateral program disbursements were covered. Projects from Partnership with Canadians Branch were left out of the evaluation’s scope given that they represent about 1% of total DFATD’s disbursements in Pakistan. While individual humanitarian assistance projects funded by the International Humanitarian Assistance Directorate were also outside the scope of the evaluation, the relationship between humanitarian assistance and development at the country program level was assessed.

- Sectoral and thematic coverage: In each sector or thematic area, the project sample represented 50% of the total disbursements for the period.

- Delivery modalities: the sample includes (i) Program-Based Approaches (PBA), and (ii) Bilateral directive and responsive projects.

- Evaluability: The sample included investments of $250,000 minimum, and sufficiently current to facilitate secondary and primary data collection.

Table 1 below presents the sample coverage statistics in terms of the first two sampling criteria, while Appendix C presents the list of projects with additional details. The sample projects were assessed using the evaluation criteria, and given nominal scores based on a five-point scale (highly satisfactory to highly unsatisfactory).

Table 1: Project sample coverage

| CIDA Sector of Focus | Population = N | Sample = n | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projects Footnote 1 | Disbursements | Proportion Footnote 2 | Projects | Disbursements | Disbursements | Proportion | |

| # | $ | % | # | $ | % | % | |

| Strengthening basic education | 6 | $53,476,741 | 35% | 3 | $45,722,803 | 85% | 45% |

| Democratic governance | 20 | $36,695,860 | 24% | 7 | $19,765,049 | 54% | 19% |

| Private sector development | 9 | $30,236,809 | 20% | 4 | $19,022,106 | 63% | 19% |

| Improving health | 7 | $26,614,191 | 17% | 3 | $17,574,191 | 66% | 17% |

| Other | 2 | $5,956,403 | 4% | 0 | $0 | 0% | 0% |

| Total | 44 | 152 980 004 | 100 % | 17 | 102 084 149 | 67 % | 100 % |

The term “legacy projects” is used in this document to refer to projects initiated under the 2001-2006 CDPF and terminated during the evaluation review period. The internal coherence of the sampled projects with humanitarian assistance was also examined and documented.

1.2 Evaluation Challenges and Limitations

The evaluation encountered a number of logistical challenges. Given insurgent attacks in some provinces and the potential for unrest after the elections, the security of the evaluation team was of concern and the limitation on its mobility to conduct interviews and site visits outside of Islamabad and Lahore was an important primary data collection constraint.

From a methodological perspective, the assessment of program level outcomes was also challenging given their scope (high level) as stated in the Program Logic Model for the 2009-2014 CDPF. There was little program level performance data, and source documents were not readily available. The evaluation’s assessment of program level outcomes relies on secondary reference documents and primary data collected from a relatively small sample of stakeholders and beneficiaries. For these reasons, the evaluation has only rated projects, and not undertaken program level ratings. It does however provide general observations and conclusions at the program level, based on the lines of evidence available.

Editorially, this report has adopted a more narrative style than other recent country program evaluations, with presentation of analysis and findings in the body of the report, and a summary of project ratings in Annex G.

2.0 Overview of Country Context and CIDA’s Country Program

2.1 A Volatile and Insecure Environment

Pakistan is a country with over 180 million people making it the world’s sixth most populous nation. With a population growth rate of approximately 1.6% it is expected to reach 230 million by 2030. Over the past decade it has faced enormous development challenges including the spill-over effects of the war in Afghanistan, internal violence and extremism, frequent natural disasters (floods, earthquakes), high levels of household food insecurity, and political instability featuring shifts between military and democratic regimes, making it a difficult environment in which to deliver development assistance. The social, cultural and religious context in Pakistan is characterised by a dominant urban elite; multiple tribal, linguistic and ethnic groups; feudal landholding relationships; a devout Muslim majority; and deep-rooted gender inequalities.

The Afghanistan conflict (as well as violence within Pakistan) has had a profound effect on Pakistan and its people, given their historical, cultural and religious ties with Afghanistan. Ordinary Afghans fleeing the conflict in their country used traditional seasonal labour migration routes to enter Pakistan (see endnotes).Footnote 1 While successive governments have been publicly aligned with the international war on terror, Pakistan has been viewed by some within the international community as being sympathetic to the Taliban and al Qaeda. Rising extremism within the country as well as the seasonal cross-border movement of Taliban insurgents into the western border provinces put the government in a precarious position of balancing the demands of various factions within the country and political pressures from the international community to take military action. The role of religion in society is ever-present, while confrontation and dialogue between moderate and extremist factions has seen ebbs and flows over the years. The new government of Prime Minister NawazSharif has already built a coalition including representatives of conservative minority parties in his cabinet.

The amount of violence in Pakistan has increased significantly in the western border regions as a result of sectarian strife and attacks on civilian populations. In 2007, Pakistan hosted 1,147,800 people living in refugee like situations due to cross-border migration.Footnote 2 In addition, Pakistan experienced 2.5 million conflict-affected internally displaced persons in 2009.Footnote 3 Frequent natural disasters have also contributed to Pakistan’s development challenges. These have displaced large populations, devastated national infrastructure assets, affected economic productivity, and contributed to existing high levels of food insecurity.

2.2 Variable Government Effectiveness

While the Government of Pakistan has often been criticised for its military spending and the neglect of the social sectors, the statistical data available appears to contradict this perception. From 2004 to 2010 public spending on the military as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product declined from 3.5% to 2.9%, health increased twofold, and education remained relatively stable. In April 2010, an ambitious programme of constitutional reform known as the 18th Amendment was passed by parliament which set in motion a very significant realignment of powers and restructuring of federal provincial accountabilities. The powers of the President were reduced, parliament oversight responsibilities were enhanced, and responsibility, if not resources, for education and local government were decentralised to the four provinces.

Open political debate in Pakistan flourished under the 2008 democratically elected government, with the media and civil society groups becoming vocal in their demands for better government. Pakistan has shown marked improvement on the World Bank’s voice and accountability indicator from a percentile rank of 20 in 2007 to 26 in 2011 and is expected to continue to improve given the peaceful transition to another democratically elected government.Footnote 4

With more than 40 million people living on less than $1.25 per day, there are daunting development challenges in Pakistan. A complicating factor is the culture of entitlement and corruption at different levels of government. The decentralisation of powers to the provinces with deficient controls on procurement and public financial management has complicated the problem. Strong Pakistani leadership will be necessary to establish the desired level of probity and accountability in public life.

2.3 Challenged Economy

Pakistan had enjoyed increasingly high rates of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth from 2001, peaking at 6-8% between 2004 and 2007. However, the global economic crisis of 2008 and ensuing recession changed the economic conditions of the country considerably. As a global trading nation it was affected more than most developing countries because it is among only 15 that have substantial trade relations with over 100 trade partners as both exporters and importers.Footnote 5 Shortages of key commodities and high inflation have reduced the US dollar exchange rate value of the Pakistani rupee by almost 100% over the past decade. Inadequate energy supplies have caused frequent power shortages that have affected economic productivity. In addition, low rates of tax collection, the cost of undertaking military campaigns against Taliban insurgents and rebel groups, and questionable macroeconomic management have put increasing pressure on the national budget.Footnote 6 While its GDP growth rate returned to 3.7% in 2012, Pakistan’s estimated GDP per capita for the same year remains relatively low at US $2,876.Footnote 7

The distribution of wealth in Pakistan is highly variable from one region to another, between urban and rural populations, and by sex.Footnote 8 Pakistan has made incremental progress but is still far from achieving the Millennium Development Goal targets on education and health. The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) takes a comprehensive approach to measuring poverty by including overlapping deprivations in health, education and the standard of living. It provides a comparative assessment of poverty in Pakistan with neighbouring countries. In South Asia, the highest MPI value is in Bangladesh (0.292 with data for 2007), followed by Pakistan (0.264 with data for 2007) and Nepal (0.217 with data for 2011). The proportion of the population living in multidimensional poverty is 58% in Bangladesh, 49% in Pakistan and 44% in Nepal, and the intensity of deprivation is 50% in Bangladesh, 53% in Pakistan and 49% in Nepal. Although a larger proportion of the population (headcount) lives in multidimensional poverty in Bangladesh than in Pakistan, the intensity of deprivation is higher in Pakistan.Footnote 9

Culture and religious beliefs both play an important role in determining the education, employment and health and safety prospects for women. Less than 20% of women achieve at least a secondary education, which has not changed significantly since 2007.Footnote 10 The expectation is for women to stay in the home to care for the family as children and as adults, irrespective of their level of education. It was noted in a report that religious edicts forbade the use of polio vaccination in the Northern Areas, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan which led to an increase in polio cases.Footnote 11

Frequent natural disasters have also contributed to Pakistan’s development challenges. The 2005 earthquake in Kashmir affected 3.5 million people, destroyed half a million homes and claimed the lives of 75,000 people. The 2007 flash floods in Balochistan and Sindh affected 2.5 million people, while the 2010 floods across almost all of Pakistan affected 20 million people from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to Punjab and Sindh provinces claiming the lives of more than 2,000 people.Footnote 12 The 2011 monsoon floods affected 5.3 million people and 1.2 million homes, and inundated 1.7 million acres of fertile arable land when massive floods swept across the Sindh province.Footnote 13 These natural disasters displaced large populations, devastated national infrastructure assets, affected economic productivity, and contributed to existing high levels of food insecurity.

2.4 International Cooperation in Pakistan

A long-term perspective is required to understand Official Development Assistance (ODA) to Pakistan today. In 2002, the calendar year following the events of September 9/11, ODA to Pakistan had reached $US 3.18 billion, two thirds of which was multilateral assistance. As the international donor community turned its attention to Afghanistan and the war on terror, ODA flows to Pakistan dropped by more than half the following year and its composition began to shift with multilateral and bilateral flows almost equal. The geo-strategic importance of Pakistan as a military ally and conduit for arms shipments into Afghanistan was embraced by Army Chief General Musharraf, who remained in power from 1999 until 2008 and aligned his government and military with international forces against the war on terror. ODA flows to Pakistan increased incrementally each year and by the end of 2007 they had again reached $US 2.46 billion with still an almost even split between multilateral and bilateral channels.

The trend line was broken in 2008 when aid flows dropped off. Donors waited to see how the country would react to the assassination of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) leader Benazir Bhutto, the outcome of the first democratic election the country had seen since 1993, and how the new government would position itself between the international forces and the extremist factions that had moved into the country. The PPP was nevertheless elected under the leadership of President Asif Ali Zardari, Bhutto’s widower, whose democratically elected government served the full five year term, a first in the history of Pakistan. Democratic elections were again held in May 2013 with a peaceful transition from one democratically elected government to another, marking another first in Pakistan’s history.

In the wake of the 2007 flash floods and monsoon rains the following year, aid flows resumed in 2009. The international donor community seemed satisfied that the Zardari government would be a good development partner, maintain the status quo and allow international forces to continue to operate on sovereign Pakistan territory with the cooperation of the Pakistani military.

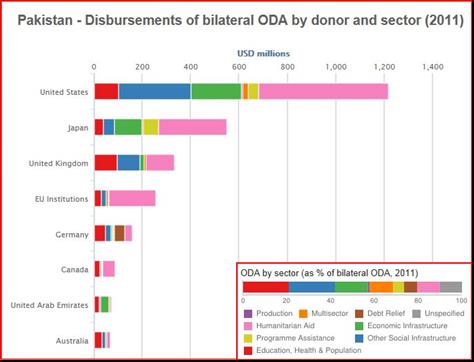

Bilateral assistance to Pakistan focused on a large number of sectors. Of note (see figure 1 below) is the significant proportion that was allocated to economic and social infrastructure by the three largest donors. Also of considerable importance was the common interest among all donors to contribute to improved education, health and population programming as part of the international agenda to reduce multidimensional poverty for the poorest segments of Pakistani society. It should also be noted that while programme assistance through government budget support and program-based approaches was relatively small, it was nevertheless present in the 2011 disbursements of several bilateral donors, including the US, Japan, UK, EU Institutions and Germany. Figure 1 also illustrates the extent to which humanitarian aid has become a significant portion of assistance in 2011 for most of the major donors.

Figure 1: Disbursements of official development assistance (ODA) by donor and sector (US $)

Source: OECD-DAC-Aid Statistics-Recipient View for Pakistan

Figure one shows the disbursement of ODA by the top eight bilateral donors. From largest to smallest, these donors are: the United States, Japan, United Kingdom, European Union Institutions, Germany, Canada, United Arab Emirates and Australia. These disbursements are disaggregated by sector. Sectors include: production, humanitarian aid, programme assistance, education, health and population, multi-sector, debt relief, economic infrastructure, other social infrastructure and unspecified. The top three sectors as a percentage of bilateral ODA in 2011 were 1) education, health and population, 2) Other social infrastructure, and 3) economic infrastructure. Humanitarian aid is also a significant portion of assistance for most of the donors.

2.5 CIDA’s Bilateral Program in Pakistan

Canada has had a long development partnership with Pakistan, spanning more than forty years, and was once among the more important bilateral donors. Pakistan was a country of focus for Canada’s bilateral development assistance during the evaluation period. The Pakistani community in Canada is estimated at 155,000 and the issuance of permanent resident visas to new immigrants has surpassed 6,000 annually. The bilateral political relationship has been one of allies in the global fight against terrorism.

The 2001-2006 CDPF objectives were: Governance - to promote democratic local governance through support to devolution and effective citizen participation, especially that of women; Social Service Delivery - to improve the quality and delivery of social services in basic education and primary health care, especially for the female population, and to increase access to those services by the poor; and, Gender Equality - to contribute to the improvement of women’s human rights, health and education, and economic empowerment.

The Pakistan Country Strategy, approved in October 2009, and the 2009-2014 CDPF, approved a month later, were the touchstone reference documents for Canada’s bilateral assistance to Pakistan. The strategic direction of the Country Strategy was consistent with the Government of Canada’s three new development priorities introduced earlier that year. They focussed on securing the future of children and youth by strengthening basic education and stimulating sustainable economic growth with a focus on women’s economic empowerment. In addition, but on an exceptional basis, the program could seek Ministerial approval for supporting “accountable democratic institutions” building on its past democratic governance programming. The program’s Logic Model (Appendix C) contained in the CDPF reflected these priorities.

Between 2007-2008 and 2011-2012, the program disbursed $153 million on 44 projects. Annual program spending ranged from a high of $35.9 million in fiscal year 2007-2008 to $27.5 million in fiscal year 2011-2012. The evaluation noted the continued decline in the number of operational projects (from 37 in 2007-2008 to 18 in 2011-2012).

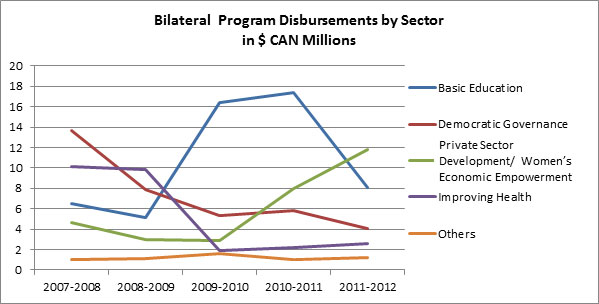

Programming in democratic governance and improving health declined sharply since social service delivery programming was no longer a priority in the 2009-2014 CDPF. The projects in these sectors came to an end, and no new projects commenced within the evaluation timeframe.Footnote 14 Programming in basic education and women’s economic empowerment increased as a new stream of projects consistent with the 2009-2014 CDPF became operational. Disbursements in basic education however dropped off as the largest projects wound down in fiscal year 2011-2012, without renewal or new proposals. See Figure 2.

Figure 2: Bilateral program sector distribution trends

Figure 2 Alternative text

| Sector | 2007-2008 | 2008-2009 | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011* | 2011-2012** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Education | $6,913,693 | $5,494,159 | $16,917,566 | $17,683,793 | $8,070,877 |

| Democratic Governance | $13,752,377 | $7,950,819 | $5,402,609 | $5,858,804 | $5,002,421 |

| Private Sector Development | $4,625,274 | $3,015,866 | $2,905,780 | $7,933,032 | $11,756,858 |

| Improving Health | $10,780,547 | $11,171,788 | $2,419,581 | $2,160,614 | $2,817,590 |

| Other | $2,214,340 | $1,089,433 | $1,618,034 | $1,044,777 | $1,189,820 |

Democratic Governance

For the period covered by the evaluation, the main thrust of the bilateral program’s Governance component was on democratic participation of civil society organisations, as well as public sector policy and administrative management in relation to local government decentralisation initiatives. Governance programming was quite substantial. The center-piece was the five-year $12 million Democratic Governance Program (DGP) which included six sub-projects of which the CIDA Devolution Support Project (CDSP) at $6.5 million was the largest.Footnote 15 A sister project, the Punjab Initiatives Fund (PIF) was a $2 million fund which supported 29 initiatives over 7 years. The other four smaller projects supported by Democratic Governance Program addressed issues such as decentralisation, community monitoring and empowerment, and judicial education. The Democratic Governance Program supported processes leading to the devolution of power, the decentralization of administration, and the participation of citizens in local governance, almost 10 years before the Pakistan Parliament devolved responsibilities to the four provincial governments.

Improving Health

Between 2007-2012, four projects were funded at $3 million and under, and three projects at over $5 million with the largest being the HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project at $12.4 million. While health programming cannot be said to have had a specific thematic focus, one third of the programming was allocated to polio eradication and HIV/AIDS prevention and surveillance, while the balance included health systems development, capacity building of front line health workers and food security.

Strengthening basic education

Strengthening basic education was the largest sector of bilateral programming within the scope of this evaluation. The overall focus was on improving primary education, including education policy development, administrative management, teacher training, and school construction. Four projects had budgets between $10 million and $20 million, the largest being the $19.7 million contribution to the Punjab Education Support Project,Footnote 16 using a program-based approach managed by the World Bank. The second largest was the $18 million Primary Education Program to reduce the Gender Gap managed by UNICEF. These two projects represented more than 50% of the total planned contributions. However, the cornerstone of the basic education program was the Debt for Education Conversion initiative (DFEC), that focused on strengthening teacher training institutions to improve the quality of basic education in four Provincial Education Departments - Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan.

Sustainable Economic Growth - Women’s Economic Empowerment

Projects in Women’s Economic Empowerment (WEE) spread evenly across the $2.0 million to $10 million range, with the largest being the Community Infrastructure Improvement Project at $10.3 million. Canadian development assistance to Pakistan has included a major gender equality component since 1995 and Canada was considered a leader among donors on this important development issue. Canada was recognised for raising gender awareness in government and through institutional capacity building of women's civil society organisations that acted as a catalyst for change. This programming area has been realigned as women’s economic empowerment under the sustainable economic growth priority. It focuses on improving the enabling environment for women’s formal employment in government policies, legislation and socio-economic programming. It also intends to build women’s capacity to engage in income generating activities through value chain development.

3.0 Main Program Level Findings

In this chapter the report first presents the various “contexts” in which the Pakistan bilateral program has had to operate, and subsequently provides a reasoned explanation of overall performance and the results achieved in relation to performance expectations.

3.1 Donors: Diverging Perceptions of Pakistan’s Role in Achieving Regional Stabilisation

The Pakistan program has to be viewed within the geo-political and security context of the region, in particular the Pakistan/Afghanistan relationship. Development assistance in this context has been increasingly used as a component of an overall engagement strategy by a political forum, the “Friends of Democratic Pakistan”, to address extremism, terrorism and resultant insecurity, which inhibit the achievement of development goals. The 2009 Country Strategy referred to a “Canadian Engagement Strategy for Pakistan” that would also address regional objectives.

“Canada’s objectives in Afghanistan will prove unattainable without concerted attention to Pakistan. As part of an emerging whole-of-government approach to Pakistan and the region, CIDA’s bilateral program is the largest operational mechanism available for engaging Pakistan and supporting Canada’s broader regional objectives.”Footnote 17

Other allies from the “Friends of Democratic Pakistan” forum have also shared this view of Pakistan’s important role in ensuring regional stability. For example the UK has integrated its development program into a wider joint security and development agenda. “UK concerns over Pakistan’s critical role in the region’s stability and security have arguably underlain the decisions over aid allocation.”Footnote 18 Similarly, the goal for Japan’s Official Development Assistance to Pakistan was to “contribute to consolidating peace and stability not only in the region but also across Asia by assisting steady development of Pakistan, which is in the process towards moderate and modern Islam and playing a crucial role as a front-line state in the fight against terrorism.”Footnote 19 The United States 2014 fiscal year budget of over a billion dollars “indicates the level of importance the Obama Administration places on a stable, democratic, and prosperous Pakistan because of its critical role in the region with respect to counterterrorism efforts, nuclear non-proliferation, regional stability, the peace process in Afghanistan, and regional economic integration and development.”Footnote 20

The strategic interests of the US, UK, Japan and other concerned allies have focussed on a stable Pakistan that can contribute to regional stability. The assessments of the 2012 elections as fair and transparent have raised the international donor community’s expectations.

The “Friends of Pakistan” and other donors, with the exception of Canada, ramped up their investments in the border areas and across the country in support of a democratic transition with the expectation that the new government of Pakistan and its military would play an important role in fighting terrorists and insurgents on their sovereign territory. The references in CIDA’s 2009-2014 CDPF to strengthening the border areas, and the ongoing programming in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province including the Northern Areas and Chitral and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, suggest that there was some expectation of mutually supportive or even common programming across the border. This was supported by the interview data.

Finding #1: The program supported projects in education and health mainly through the Balochistan Responsive Fund and FATA supported projects (FATA: Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan),although the level of support to actual initiatives did not in the end correspond to the emphasis suggested in the strategic planning documents.

3.2 Pakistan: Evolving Government Policy Framework

The Canadian development policy framework for Pakistan evolved considerably over the timeframe of the evaluation. This was a key contextual factor influencing the success and sustainability for some of the projects. The Government of Pakistan had a solid record of implementing the reforms identified in the interim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) from 2001 to 2003. It then engaged in a broad stakeholder consultation process with sector ministries, provinces, elected district governments and civil society organisations in the preparation of the PRSP I (2003) which reflected considerable country ownership of the development process.Footnote 21 The 2001-2006 CIDA CDPF took its cues from the PRSP I priorities, which included development of administrative and financial mechanisms to advance devolution, and improvement of social service delivery in health and education.

In 2008, the Poverty Reduction Strategic Paper II (PRSP II) was to reflect the country’s new development priorities. While the PRSP I was a requirement for debt write-off eligibility under the Highly Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) initiative, there was no similar incentive for PRSP II (2010).Footnote 22 The PRSP II set out new development priorities to regain macroeconomic stability while enhancing some safety nets for the poor.Footnote 23 Its economic growth orientation focussed on harnessing the demographic dividend, easing credit and microfinance for small and medium enterprises, and generally achieving a national competitive advantage that would reduce overall poverty.Footnote 24 While information sessions were held with donors, PRSP II didn’t involve the donor community to any significant extent, and has not had much subsequent influence on donor development policy dialogue. The government-led Pakistan Development Forum met only once in 2010. Donor coordination in the form of thematic or sector working groups was almost non-existent and the evaluation found only a handful of examples of bilateral collaboration and joint-funding. The point was made to the evaluation that the Government of Pakistan had many strategies, for example, the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper I & II, the Five-Year Economic Plan, a number of Medium Term Development Frameworks, Vision 2020. Given this confusing context, most donors could not decide which national strategy they should align with and ended up designing their own programming.

Finding #2: The Government of Pakistan’s development policy framework became increasingly complex for all donors. This contributed to the chaotic development context in which the CIDA program had to operate.

3.3 Canada: Absence of Clear Policy Guidance

Like other donors, CIDA did not explicitly use the Poverty Reduction Strategic Paper II objectives in framing its bilateral assistance program. In August 2009, following formal consultations at working level in 2007 and 2008, CIDA’s Minister of International Cooperation visited Pakistan and held consultations about the broad lines of programming with Government of Pakistan officials including President Zardari.Footnote 25 A few months later the 2009-2014 CDPF was approved with a focus on “securing the future of children and youth” by strengthening basic education and stimulating “sustainable economic growth” through women’s economic empowerment. There were high expectations for bilateral program funding, notionally set at $50 million annually.Footnote 26

Six projects have been approved from 2009 to date, for a lower level of investment than originally anticipated. Interviews suggest that program staff have perceived a lack of overall guidance regarding what kind and level of investment to proceed with. Limited new programming eventually reduced overall expenditure. Other donors and local partners noted Canada’s reduced presence. Respondents generally, and beneficiaries in particular, expressed concern at the change in Canada’s support, particularly in governance and gender equality where it had provided significant leadership for over 25 years.

Finding #3: While there was an approved Pakistan Country Strategy and CDPF in place, interviews suggest that these came to be perceived as inaccurate guides for staff on desired program direction, and there was a lack of alternative explicit guidance on what to put forward.

3.4 CIDA: Ongoing Organisational Change

The Pakistan bilateral program has undergone a number of organisational changes since the approval of the 2009 Country Strategy that affected its operational and human resource capacity. In 2009 it was moved out of the CIDA Asia Branch and co-located with the Afghanistan Task Force. In 2012 the Pakistan Program was reintegrated in the Geographic Programs Branch, Europe, Middle East and Maghreb Directorate when the Afghanistan/Pakistan Task Force was dismantled.

Subsequent to the approval of the 2009-2014 CDPF the bilateral program was scheduled for decentralisation with a field-based Country Program Director, but the decision was reversed in 2010. Nevertheless, the Senior Program Analyst position was decentralised and the field staff complement increased by two full time equivalent positions. The partial decentralisation resulted in unclear lines of authority vis-à-vis the Head of Aid. Interview respondents suggest that when added to the usual attrition due to retirements and redeployment, these changes led to reduced efficiency in program planning and implementation.

Finding # 4: The planning and implementation efficiency of the program was hampered by the number of organisational changes.

3.5 A Gap in the Relief, Recovery and Development Continuum

Significant Canadian humanitarian assistance funding flowed into Pakistan after a succession of natural disasters. Total disbursements were estimated at approximately $151 million of which $80 million was in 2010 and $18 million in 2011.

As per its mandate, CIDA’s International Humanitarian Assistance Program (IHA) focused on immediate lifesaving activities, while the bilateral program focussed on reconstruction and rehabilitation. There was a very high level of satisfaction expressed with how IHA staff in Ottawa and bilateral program staff in Pakistan worked together. Some of the reasons cited included the involvement of IHA staff in the selection of bilateral staff for posting to Pakistan to ensure that they had the requisite skills to work effectively in emergencies and the creation of a liaison position in the Canadian High Commission (CHC). CIDA provided surge capacity in support of the CHC during emergencies and the whole-of-government approach was effectively implemented by the CHC, which was consistently excellent in supporting humanitarian work. In recognition of its contribution to the 2010 floods the Flood Coordination Team won the Canadian 2011 Public Service Award of Excellence.

On the relief, recovery and reconstruction continuum, IHA had the lead responsibility for “relief” and the bilateral program for “reconstruction”, while “recovery” fell in between due to funding and mandate definitions. Emergency humanitarian projects were announced as standalone relief projects, often implemented through IHA’s matching funds mechanism with registered charitable organisations without reference as to how they might link with ongoing development programming and expected outcomes. IHA was not mandated to respond beyond its short term (one year or less) emergency relief, nor did it have the human or financial resources to support additional recovery projects. The bilateral program was not mandated to be responsive to the needs of beneficiaries in the aftermath of a natural disaster.

The challenge identified by interview respondents has been to find ways for the bilateral program to build on IHA relief projects. There have been attempts to bridge humanitarian assistance and development in order to address the gap in early recovery programming. Adding to existing bilateral projects was an expeditious way of getting support to the people who needed it the most in an emergency. For instance, while there was no original provision in the Women Economic Empowerment portfolio that required proactive reactions to humanitarian crisis, a prompt response to emergencies was nevertheless achieved by several projects.

However, the absence of formal mandates and mechanisms has meant that joint program planning was rare, the exception and not the rule. There was no requirement, expectation or consistent champion for bridge-building between emergency relief and development programming. These findings confirmed those of the 2012 Corporate Evaluation of CIDA’s Humanitarian Assistance which stated that the “linkage between relief, recovery and development continues to pose funding and mandate challenges.”Footnote 27

Finding # 5: IHA had the lead responsibility for “relief” and the bilateral program for “reconstruction”, while “recovery” fell in between due to funding and mandate definitions. The capacity of the bilateral program to create linkages between relief, recovery and development programming has been constrained by the lack of corporate emphasis on this issue, and by limited attention to it in country program planning.

4.0 Main Project Level Findings by Evaluation Criteria

4.1 Effectiveness

The evaluation examined whether the projects achieved outcomes of importance relative to performance expectations, taking into consideration the development context.

Governance

The Supporting Democratic Development and Governance (SDDG) project file documentation, monitoring reports and interview data indicate that the South-Asia Partnership – Pakistan (SAP-PK) and its partners facilitated peasants and workers in influencing policies such as the Constitutional Amendment package, the Farmer’s Policy, the Allocation Act in Sindh, and policy research on the political economy of sugar cane and wheat in Punjab. In the agriculture sector, SDDG had an “impact at the provincial and/or national levels”Footnote 28 as a result of its policy influence and advocacy activities with a focus on mobilizing peasants and workers across the country for workers’ rights. Many of these SDDG activities in agriculture reached a critical mass throughout Pakistan and “will have lasting impact.”Footnote 29 The project was influential in bringing about change in the areas of violence against women, climate change, corporate farming policy, land distribution, crop and agricultural input pricing and other issues that affected SAP-PK’s poor, rural constituency. The 3rd Voluntary Sector Monitoring ReportFootnote 30 and subsequent monitoring reports also noted the contribution of the SDDG to the 2008 national election process and SAP-PK’s participation in the work of the Free and Fair Election Network and the Pakistan Coalition for Free and Democratic Elections.

Another project with noteworthy results was the Program for the Advancement of Gender Equality (PAGE) where many of the 89 sub-projects had policy influence. For example, one sub-project partner made a film and presented evidence to the Supreme Court of Pakistan that led the Court to abolish the common practice in rural areas of ‘swara’ and ‘vani’ which allowed the exchange of a girl or woman family member as a chattel to compensate for a murder committed by a man.Footnote 31 Another sub-project brought about changes to the Code of Conduct for Gender Justice at the Workplace by working with the Ministry of Women’s Development and the Ministry of Labour co-chaired by the PAGE partner. A sub-project with the International Organisation for Migration resulted in the development of a National Plan of Action on human trafficking by working with multiple stakeholders, including government, civil society organisations, and contributed to change in the Sexual Harassment Law.Footnote 32 Documented examples of policy influence and advocacy that led to positive change were achieved by over one quarter of the PAGE sub-projects as described in the End of Project Report titled “Turning a New Page for Women”. The most significant change achieved by PAGE was that more women believed change was possible and more men were sensitized to the benefits of gender equality and stopped blocking gender equality initiatives. This provides evidence of the effectiveness of the Pakistan country program in the area of governance and gender equality.Footnote 33

There were very few health sector examples of government policy influence and resulting changes. One which stood out however was the influence the HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project (HASP) had on the writing of the Ordinance on Prevention of HIV/AIDS in Sindh signed into law in 2013.Footnote 34 Projects linked most closely to local organizations with large constituencies had the most success in advocacy efforts leading to policy changes.

Finding 6: The program and its partners were integrally involved in wide spread advocacy campaigns, which created policy dialogue opportunities that led to positive policy changes.

Children and Youth: Basic Education

Access to quality primary education for boys and girls was the major focus in this programming area which was to be achieved through improved quality of teacher training and improved management of public education systems. The two most important among the sampled projects were the national Debt for Education Conversion (DFEC) initiative and the Punjab Education Development Project (PEDP), a program-based approach to education sector reform. The Canada-Pakistan Basic Education Project (CPBEP) was rated highly satisfactory for development results. Some notable achievements were also documented for the Communications for Enhanced Social Sector Development (CESSD II) and UNICEF’s Primary Education to Reduce the Gender Gap (PERGG) project.

Improvement in the quality of teacher training programmes was achieved at the national, provincial and district levels, through the Federal College of Education (FCE) and National Science Institute for Teacher Education (NISTE), Provincial Teacher Training Institutes (PTTI) and Government Colleges for Elementary Teachers (GCET). The DFEC civil works component was instrumental in creating an enabling learning environment at FCE and NISTE for gender-sensitive and learner-centred pre-service and in-service training provided to male and female teachers, head teachers and teacher educators for primary and middle school levels. Approximately 1,000 scholarships to the FCE were provided to male and female teacher candidates for Bachelor and Diploma level training. The Canada-Pakistan Basic Education Project developed standard operational procedures for gender sensitive curriculum review and the National Curriculum Framework for curriculum revisions with far reaching application by Provincial Bureaus of Curriculum and Extension centers. The national apex institutions, FCE and NISTE, met their in-service teacher training targets totalling approximately 4,600 teachers and 600 head teachers. The PTTIs collectively trained approximately 25,000 elementary and middle school teachers. While these numbers were impressive, they represented only a small fraction of the number of elementary school teachers in Pakistan.

In terms of improved management of public education systems there were a number of demonstrated examples of policy influence and advocacy that generated notable development results. For example, the Debt for Education Conversion (DFEC) has influenced government to spend more on teacher training at the national and provincial levels. CIDA program staff involved in the Punjab Education Development Project (PEDP) successfully advocated for the adoption of a more holistic Punjab Education Sector Plan and for a teacher recruitment policy that was more merit based. The Canada-Pakistan Basic Education Project (CPBEP) worked with the District Education Offices in Multan and Lohdran Districts on policy development and planning resulting in the formulation of gender sensitive District Education Action Plans considered as a model by the Punjab Education Schools Department. UNICEF’s Primary Education to Reduce the Gender Gap (PERGG) project institutionalised the District Education Management Information System, which resulted in improvements in the collection, compilation and use of data by District Education Offices and the Balochistan Education Department. The Communications for Enhanced Social Sector Development (CESSD II) strengthened 849 Parent Teacher Councils and rehabilitated 156 Government Primary Schools.

Finding 7: Although based on a limited number of interviews with beneficiaries, there is evidence of improved access to quality public sector education services for boys and girls.

Sustainable Economic Growth: Women’s Economic Empowerment

Better participation of women in economic growth was to be achieved through improved labour conditions for women’s formal and informal employment, and improved capacities of women for remunerative activities. The three sampled national level projects were Promoting Employment for Women (PEW); Pursestrings and Pathways (P&P); and the Program for the Advancement of Gender Equality (PAGE). Regionally focussed were the Community Infrastructure Improvement (CII) project in Sindh and Punjab Provinces, and the Institutional Development for Poverty Reduction (IDPR) project in the Northern Areas and Chitral.

There were demonstrated examples of improved labour conditions. For example, the P&P project sponsored the 2011 Conference on “Women and Economy” in Karachi which raised the profile of women entrepreneurs in Pakistan and awareness within government of women’s rights to gainful formal and informal employment. This was a first and important step in bringing about policy change to enhance women’s economic empowerment. A PAGE sub-project brought about policy changes to the Code of Conduct for Gender Justice in the Workplace by working with the Ministry of Women’s Development and the Ministry of Labour. The Promoting Employment for Women project (PEW) successfully lobbied at a national government level to adopt conventions and pass legislation to protect women workers. For example, the International Labor Organisation Convention 177 on Home Work was ratified and the Protection Against the Harassment of Women in the Workplace Act was passed into legislation. The project stressed the importance of fair remuneration, environmental and occupational health and safety, and the creation of a social protection program for formal and informal workers. The Departments of Labour were duly notified thereafter by the Provincial governments to establish Gender Units, and received technical assistance and gender training by the PEW project.

In terms of improved capacities of women for remunerative activity there were a limited number of demonstrated examples from among the sampled projects. The Pursestrings and Pathways project achieved significant progress in linking women entrepreneurs to viable markets through value chain development in four provinces. It exceeded its active women entrepreneur registration targets in the following four sub-sectors: 1) fresh milk (Punjab); 2) embellished fabrics (Balochistan and others); 3) seedlings (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa); and 4) glass bangles (Sindh). A total of 17,493 clients directly accessed project services. Given an average household size of 6.8 people, that implies 119,000 indirect beneficiaries.

Finding 8: There was a contribution to increased participation of women in national economic growth, although its scale must be weighed against the size of the challenge. Most important were the policy, legislative and regulatory changes that were brought about, as they will contribute to creating the enabling conditions for women to participate more freely in formal and non-formal employment without harassment.

Cross-Cutting Themes

Gender Equality

The three pillars of CIDA’s Policy on Gender Equality focus on women’s rights, access to development resources, and decision-making. The evaluation analysed the gender outcomes achieved by the sampled projects.

To support women and girls in the realization of their full human rights, the Balochistan Response Fund achieved notable results in promoting the rights of women and girls to education and health services by: fully rehabilitating 30 schools of which 27 were for girls; providing separate washrooms for another 20 schools serving over 6,000 children; improving reproductive health units; and raising the awareness of 10,000 women and girls on reproductive health rights, female hygiene and their rights to securing clean water.

To reduce gender inequalities in access to, and control over, the resources and benefits of development, women’s empowerment and their acceptance in a non-traditional income-earning role was an outcome of the Community Infrastructure Improvement Project (CIIP). Women in Union Councils in the communities where CIIP was implemented looked up to Road Maintenance Team women working as “role models”, and there was a concomitant increase in the ratio of women working outside their homes over the 18 months in the assessed communities.

To advance women’s equal participation with men as decision makers in shaping sustainable development of their societies, the Agha Khan Rural Support Program (AKRSP) actively worked to encourage women to participate in the election process. Subsequently, 288 women entered the Union Councils, Municipal Committees and District Councils as members in all six districts of the Northern Areas. AKRSP followed up with intensive capacity building support, under the Institutional Development for Poverty Reduction project (IDPR), to hundreds of elected men and women at all levels.

Gender-specific projects, either under Women’s Economic Empowerment or Governance or Education, had set the trend for many development stakeholders in Pakistan. For example, upon successful completion of the Program for Advancement of Gender (PAGE), the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) initiated a very similar but larger gender equity project. Likewise, the establishment of local support organisations under the Institutional Development for Poverty Reduction Project (IDPR) was considered by interview respondents to be a great achievement in supporting freedom of expression. The project was replicated in other parts of the country, by other development partners, including the Himat Foundation, Trocaire, Caretas and Cesvi. After the successful completion of Pathways & Pursestrings Project (P&P), the Fresh Milk sub-project was taken over by other processors who recognised the developmental and economic value of the results achieved.

The evaluation also assessed compliance with the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA) for each of the programming areas. Only four projects were subject to the CEAA process. For the Balochistan Responsive Fund and the Program for Advancement of Gender Equality the CEAA process was applied at the sub-project level. For UNICEF’s Primary Education to Reduce the Gender Gap (PERGG), the Master Agreement between CIDA and UNICEF specified that UNICEF could use its own Programme Policy Procedures Manual to ensure adherence, although there was no evaluation data found to confirm that this was actually done. The Institutional Development for Poverty Reduction Project Contribution Agreement was amended to ensure application of CEAA at the sub-project level. In all, the evaluation was able to confirm compliance by all but one project (PERGG) for which CIDA delegated responsibility to UNICEF.

Finding 9: The bilateral program has played a significant role for many years in mobilising civil society organisations, women’s organisations, local governance structures and educational institutions at the grassroots level.

4.2 Sustainability

The evaluation examined whether project results achieved were sustainable without DFATD’s ongoing financial support. Sustainability of the sampled projects was assessed with regard to the presence of a stable development policy framework, as well as the institutional and financial capacity of development partners to maintain the mechanisms that generated the outcomes.

Some projects closed before achieving significant positive outcomes, an indication that there was insufficient planning for sustainability. Three of the legacy projects in governance and health (the Systems-Oriented Health Intervention Project, the HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project, and the CIDA Devolution Support Project) suffered from not having been well integrated into Pakistani partner organizations and structures. This diminished chances for the sustainability of the results achieved. Projects managed by local implementing partners and executing agencies had greater success in institutionalising their achievements and/or embedding them in the local culture. Similarly, the two Funds (Balochistan Responsive Fund – BFR, and the Program for Advancement of Gender Equality – PAGE), also had good potential for sustainability of advocacy outcomes and development results by being embedded within the civil society organisations and communities.

In the education sector, the sustainability of project outcomes was highly dependent on local socio-economic conditions, host government development priorities, and the presence of follow-on donor support, other than CIDA. The likelihood that newly established civil society and local governance organizations, particularly outside the Punjab, would have the capacity, access to resources and government support needed to continue the development process was unconvincing, at least without additional donor funding. The presence or potential of follow-on donor support was however encouraging for a good number of projects across all the sectors and regions. Some projects had already been passed off to other donors, and those projects managed by UN Agencies and local non-governmental organisations with good reputations will likely continue to attract donor funding. Policy influence and advocacy results that led to changes in government policies, legislation, laws and resource allocations had the best potential to sustain ongoing positive outcomes, as well as government funded education reform in the Punjab.

Women’s Economic Empowerment project results are likely to be sustained at the level of individuals on account of strategic policy interventions, awareness building, training and exposure to markets and employment opportunities, as was the case in all of the sampled projects. However, at organizational and institutional level the likelihood of sustainability is varied. The results of some of the projects are likely to be sustained as in case of the Institutional Development for Poverty Reduction Project (IDPR) and the Community Infrastructure Improvement Project (CIIP). However, interventions involving support to community and women’s organisations, local governance structures and government institutions are unlikely to sustain results without ongoing policy advocacy and financial support. The short timeframes of many projects have not facilitated full sustainability.

One of the key factors for sustainability is the financial capacity of partner organisations to maintain the mechanisms that generated the results. This wasn’t always explicitly taken into account in the design of projects. Some projects have been adopted by the other donor agencies, as in the case of Program for Advancement of Gender Equality (PAGE) and IDPR projects; by the Government of Sindh in the case of the CIIP; and by other food processors in the case of the Pathways & Pursestrings Project (P&P) Fresh Milk sub-project.

Finding 10: Achieving sustainable results was challenging for most projects given the weak institutional capacities of many partner organisations. The sustainability of results for all but a handful of projects would be in jeopardy were it not for follow-on funding from other donors.

4.3 Relevance generally satisfactory

The evaluation examined the extent to which project objectives and activities were consistent with beneficiaries’ requirements and country needs.

The CIDA legacy projects in governance and health were well aligned with the 2001-2006 CDPF as these projects were almost all designed and approved during that time period. The relevance of the results achieved in governance and health were most evident with the Balochistan Responsive Fund, the Program for Advancement of Gender Equality and the CIDA Devolution Support Project/Punjab Initiative Fund, which were fully operational at the time of the 2009-2014 CDPF approval. They had the added advantage as Funds of being able to solicit and approve second and third round sub-projects that were aligned with the new priorities.

The interview data from a broad range of stakeholders, including government representatives, other donors, and project beneficiaries, attested to Canada’s excellent reputation in gender equality and governance programming over its 25 years of support to Pakistan – an indication that programming was consistent with beneficiaries’ requirements. The program’s reputation had been built through the many small grass-roots projects with civil society organisations, local governance structures and district school administrations. Projects in health were more recent, received financial support over shorter periods of time, and were less widely acknowledged by government partners and beneficiaries alike.

The development and gender equality outcomes achieved by education projects planned and implemented under the 2001-2006 CDPF, were relevant, demonstrating enhanced capacity of primary schools, education apex institutions and systems to deliver more and improved basic education services, especially to women, girl children and other disadvantaged groups. The results achieved by the education portfolio were also relevant to the 2009-2014 CDPF and to the development partners and individual beneficiaries that have been involved. The increased focus in the 2009-2014 CDPF on the management of the public education system and teacher training corresponded directly with the objectives of the Punjab education reform. In fact, the CDPF expected results for “Securing the Future of Children and Youth” remained unchanged, which ensured that the results achieved of both past and current projects stayed aligned. While stakeholders’ recognition and appreciation of the outcomes achieved in education are overall quite positive, the geographic scope and numbers of beneficiaries reached are limited in comparison to the magnitude of need.

The Women Economic Empowerment portfolio is well aligned with the CDPF priorities. Projects have been found to be need-based, and contributory to the political, economic and social participation of women in Pakistan’s development processes, including the reduction of the marginalisation of women. Projects are aligned with Pakistan’s Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper II which focused on protecting the poor and vulnerable. CIDA’s 2009 Pakistan Country Strategy and 2009-2014 CDPF made Women’s Economic Empowerment, one of its two main programming pillars, consistent with CIDA’s 1999 Policy on Gender Equality. The simultaneous development activities by different development partners, as for instance ‘gender training’ or ‘awareness of women’s rights,’ to some extent caused an overlapping of efforts. Yet, in light of the gravity of the women’s issues being addressed, there was relevant need for many voices and simultaneous activities to address the needs of destitute and marginalised women in Pakistan.

Finding 11: Based on alignment with CIDA’s CDPF, in addition to beneficiary and donor recognition of the value of the individual projects, the relevance of the results achieved is satisfactory. The policy influence and advocacy results achieved by the Institutional Development for Poverty Reduction Program and the Promoting Employment for Women Project were the most relevant. From the grassroots perspective the benefits to individual women of the Community Infrastructure Improvement Project and the Pathways & Pursestrings Project, though limited in scale, were very relevant to those directly involved.

4.4 Satisfactory coherence with other development actors

The evaluation examined how projects in the three sectors were coordinated with other relevant development actors, including government at different levels and local civil society organisations.

Regardless of the type of program or project, external coherence of projects was grounded in relevant policy frameworks and participatory approaches. There was satisfactory coherence at the provincial, district and community organization levels for governance and health projects. The Program for Advancement of Gender Equality (PAGE) stood out as exceptional with many policy advocacy successes. It supported 89 separate initiatives which were responsive to the objectives of women’s organizations and encouraged policy dialogue at all levels of Pakistani society. Other gender equality projects, which were not part of the evaluation sample, were coherent with the Constitution of Pakistan and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) to which Pakistan was a signatory.Footnote 35

In education, the sample projects for the most part reflected good integration across different levels of government. Policy dialogue and coordination were also evident. Since its inception, the Debt for Education Conversion initiative (DFEC) was to assist the Ministry of Education, Federal Directorate, four Provincial Education Departments and the teacher training institutions in their respective jurisdictions to maintain adequate and sustainable infrastructure, curriculum and module development and teacher training.Footnote 36 The design was vertically integrated down to the district level with suitable governance bodies to ensure coordination among key stakeholders, and with the central government structures (Economic Affairs Division, Planning and Development Commission, and Finance Department).

One of the projects in the education portfolio, launched in 2003, was the Canada-Pakistan Basic Education Project (CPBEP) which was largely a capacity development project, focusing on developing human and institutional resources in the delivery of basic education services. The project design was also vertically integrated and operated at three levels of the education system: federal, provincial and district. At the federal level, it provided technical assistance in curriculum development to improve teacher training programs at the Federal College of Education (FCE), a teacher training institution that provided pre-service training for teachers from the federally-administered areas and all four provinces. The DFEC initiative and CPBEP complemented one another in that the former enhanced the learning environment through civil works and supported teacher training course offerings, while the latter worked in conjunction with the Ministry of Education, Curriculum Wing, to strengthen curriculum review and development for teacher training. Similar complementarity was noted at the provincial level, where the project had worked with the Directorate of Staff Development, Punjab Department of Education and the University of Education, Lahore to improve the design and delivery of pre-service programs. The University played a pivotal role in pre-service teacher training in 42 teacher training institutes across Punjab. At the district level, the project worked with the educational administrations of two large districts, Multan and Lodhran to strengthen capacity in: planning; financial management; the development of a sound Education Management Information System; teacher and program monitoring and evaluation; office management; interaction with the community; and gender analytical skills.Footnote 37

For Women’s Economic Empowerment (WEE), the Promoting Women Employment (PEW) and Institutional Development for Poverty Reduction (IDPR) projects were reflective of tripartite relationships between donor agencies, Government of Pakistan and civil society organizations. Interviews and project documents revealed that the Community Infrastructure Improvement project went well beyond a tripartite relationship by partnering with private sector entities like Telenor and Tameer Bank. Likewise, the Pathway & Pursestrings project (P&P) fresh milk sub-project was implemented in partnership with Haleeb Foods and others. Another significant coherence feature of the WEE portfolio was capacity building with federal government staff through conferences, workshops, policy dialogue, documentation dissemination, and networking with peer groups for resource pooling. Many projects like the IDPR and the P&P had extensive collaboration and synergy with other donor funded development projects.

The interview data reflected the lead role that the Canadian High Commission and Program Support Unit played in fostering donor coordination. CIDA used annual sector coordination events in Islamabad to encourage linkages with other related projects, and with other potential partners, government actors, and other donors. Project staff was regularly invited by CIDA to Inter-Agency Gender and Development Group meetings, the Women’s Economic Empowerment Forum meetings and bi-annual workshops for Gender Focal Points. These regular fora as well as the 2008 CIDA-organized “Reflection Sharing Conference” were helpful in sharing experiences, building linkages with other development partners and minimizing the duplication of effort. CIDA also maintained and updated for many years the GoP Economic Affairs Division web portal “Development Assistance Data” (DAD) to which many other bilateral and multilateral donors provided data inputs. Nevertheless, this evaluation was hard pressed to find examples of donor collaboration, joint funding of projects or follow-up financial support for PSE/WEE projects with the exception of follow-up funding from the Food and Agriculture Organisation FAO and USAID for MEDA Women’s Economic Empowerment and value chain development-focussed projects.Footnote 38

Finding 12: Most projects in the three sectors reflected good vertical integration from the district to the provincial and in some cases to the federal level. Policy dialogue and coordination at chosen levels of government were also evident, and where projects focussed on the community level a participatory approach responding to local needs was employed. Partnerships with private sector entities were innovative and contributed to the sustainability of these projects.

4.5 Efficiency

The evaluation examined whether the human and financial resources allocated to the project portfolio were reasonable, and whether they were used economically and efficiently in generating outputs.

Using Canadian executing agencies for the two health projects (the Systems-Oriented Health Intervention Project – SOHIP, and the HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project – HASP), as well as the CIDA Devolution Support Project (CDSP) governance project, incurred high costs for in-country office infrastructure and Canadian management staff who were paid overseas allowances and risk premiums. The interview data from diverse sources characterised these projects as “not cost-efficient”, although they were recognised as producing high quality outputs. As well, the reference documentation and interview data indicated that the time needed to design and approve these two health projects, using the directive modality, was slow (almost three years for HASP, and almost four years for SOHIP). This planning timeframe made it challenging to ensure coherence between the project plans and the reality on the ground for which they were initially designed.

More efficient were the Supporting Democratic Development and Governance Project (SDDG) managed by a local executing agency,Footnote 39 and the World Food Program’s AFIH project, which benefitted from economies of scale and a high proportion of locally engaged staff. In education, four of the six projects in the sample achieved good outputs using local human resources, and demonstrated sound management and use of financial resources. Two cornerstone projects of the education portfolio, Debt for Education Conversion and Punjab Education Development Project, were less satisfactory, each for different reasons.

The Women’s Economic Empowerment projects demonstrated efficient planning and approval processes, averaging a reasonable 12 months from concept paper to launch. They were also cost effective in use of inputs relative to outcomes achieved. They demonstrated efficient local resource utilization, tapping of appropriate international expertise when necessary. Extensive collaboration with community based-organizations had the effect of reducing operational costs. Synergies with other executing agency and donors projects contributed to the overall efficiency.

Finding 13: Current projects are efficient in their use of human and financial resources.

4.6 Aid Effectiveness Practices

The evaluation examined whether the Paris Declaration Principles on Aid Effectiveness were reflected in the management and implementation of the project portfolio.