Canada’s State of Trade: Trade and Investment Update – 2018

Table of Contents

- A Message from the Minister

- Executive Summary

- Global Economic and Trade Performance

- Economic and Trade Developments: Regional and Country Overview

- Canada’s Economic Performance

- Canada’s International Transactions

- Key Developments in Canadian Merchandise Trade

- Canada’s Foreign Direct Investment Performance

- Special Feature: Canada’s Services Trade Performance

PDF Version (7.1 MB)

Canada State of Trade – Message from the Minister

The Honourable François-Philippe Champagne MP

Minister of International Trade

As Canada’s Minister of International Trade, I’m delighted to present the State of Trade Report for 2018. The past year has been a record one for Canadian trade successes across the globe as we continue to expand Canada’s trade footprint to new markets and new opportunities.

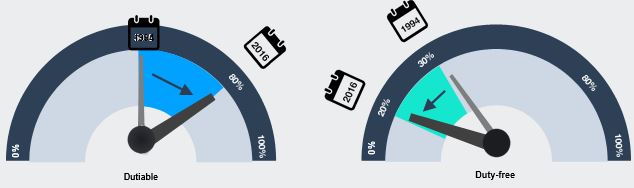

From the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the European Union, which came into force in September 2017, to the historic signing of the 11-country Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (CPTPP) in March of this year, Canada has led the way in making trade fair and accessible to more citizens from almost every corner of the world.

When the CPTPP is fully in force, Canada will have preferential market access via 14 trade agreements to 51 countries with nearly 1.5 billion consumers and a combined GDP of US$49.3 trillion.

Trade is in Canada’s DNA and it’s vital to our economic prosperity.

To ensure our continuing prosperity, we are diversifying our markets and pursuing a progressive trade agenda. This past year, the momentum for Canada’s trade diversification continued with the launch of negotiations for new free trade agreements with the Pacific Alliance trade bloc in October 2017 and the Mercosur member countries in March 2018.

Our government’s ongoing commitment to expanding and diversifying Canada’s trade and investment ties with countries around the world is reflected in this year’s State of Trade Report.

In 2017, Canada’s merchandise exports rose 5.7 percent to an all-time high of $546.7 billion, which was $29.2 billion above the 2016 level. With merchandise imports also rising to record levels, total merchandise trade also reached another all-time record of $1,108 billion. Canada’s exports to countries such as Japan, India, South Korea, Germany and the United Kingdom rose in 2017, as did those to China.

More trade and more investment means more economic growth and more good-paying jobs to help further strengthen Canada’s middle class.

Our government’s approach is to ensure that increased trade and investment are about a march to the top, rather than a race to the bottom, when it comes to consumer rights, environmental protection, labour standards, and the rights of government to regulate in the public interest.

Canada has led the way in advancing gender equality and women’s empowerment through our international engagement, including during our G7 Presidency this year. Our government is also playing a leading role in helping more Indigenous people, members of the LGBTQ2 community, and youth succeed in today’s economy.

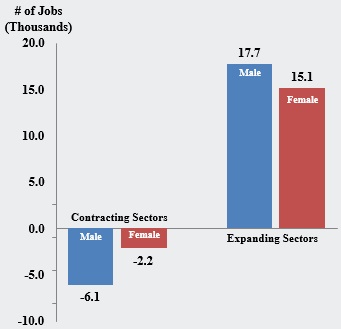

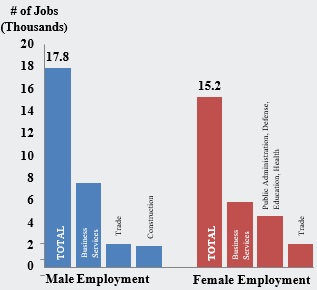

This year’s State of Trade Report includes an analysis that illustrates the differentiated labour market impacts of trade agreements in Canada by gender and complements previous analysis of women-owned exporting businesses. We know that advancing gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls is the most effective way to foster prosperity, create lasting peace, and achieve sustainable development.

All over the globe, we are making headway in securing better terms for trade and in fostering crucial progressive ambitions on gender, for workers, and for the environment. Canada’s progressive trade agenda is positioning us to accomplish this and much more in the years ahead.

The Honourable François-Philippe Champagne Minister of International Trade

Executive Summary

Ten years after the outbreak of a global financial and economic crisis, a long-delayed synchronized global recovery in manufacturing, trade and investment made an appearance in 2017. While long expected, it still exceeded expectations, as the global economy grew 3.2 percentFootnote 1 in real terms. In particular, economic growth in the eurozone, Japan, the United States and China was notably above expectations. Russia and Brazil came out of recession, with the surrounding regions benefiting from their recovery.

The advanced economies are now closing the books on the economic cycle associated with the Great Recession, with labour and investment markets once again approaching normality and the economic slack almost drained out of the system. Global financial conditions will remain accommodative in the short term, with growth picking up from 2.3 percentFootnote 2 in 2017 to 2.5 percent in 2018. In the long term, aging populations and relatively weaker productivity growth will remain key challenges.

Growth in the emerging and developing economies finally picked up after failing to grow substantially for six consecutive years, and more good news is expected in the short term. Rising commodity prices are helping commodity exporters (the majority of this group) to shore up their balances and let their private consumption recover. The IMF expects economic growth to accelerate from 4.8 percent in 2017 to 4.9 percent in 2018, and above 5 percent next year.

Rising confidence under favourable fiscal, monetary and external conditions was behind the rebound in investment, which in turn boosted global trade volumes. World merchandise trade recorded its largest increase in six years, expanding 4.7 percent. Supporting trade activity is a continuing upward push in commodity prices, backed by strengthening consumer demand. Large exporters such as Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States made key contributions to global trade growth.

The largest trade volume gains in 2017 were in imports from developing economies, which soared 7.2 percent. Developed economies’ imports also grew well at 3.1 percent. Real exports by developing economies grew 5.7 percent and 3.5 percent for developed economies. Trade recovery was broad across all regions, with emerging Asia leading the way. In nominal terms, world imports expanded 10.7 percent in 2017 after two years of declines and reached US$17.6 trillion. China recaptured its status as the world’s greatest merchandise trader, lost to the United States in 2016. World imports of commercial services also rose 6.5 percent in value in 2017, to US$5.1 trillion. The WTO expects world trade growth to level off slightly to 4.4 percent in 2018 and to moderate to 4.0 percent in 2019.

Conditions differed among the economies and regions that are key to Canadian commercial interests. The United States’ economy was slow out of the gate early in 2017, but made up the lost ground and accelerated strongly for the remainder of the year with 3.0-percent average annualized growth in the last three quarters, and 2.3 percent overall in 2017. Unemployment is close to historic lows, fiscal stimulus is in play and strong consumer spending and investment is expected to propel the economy to 2.9-percent growth in 2018.

Mexico’s economy slowed down to a 2.0-percent pace in 2017, as activity was close to recession levels in the second half of the year. Fiscal pressures and high inflation, which prevented the government and the central bank from coming to the rescue, were largely responsible. The NAFTA renegotiation process remains the gravest threat to the economy, with total investment contracting 1.0 percent in 2017 and FDI declining 0.2 percent partly due to the uncertainty. Mexico’s near-term outlook is clouded due to uncertainty emanating from the United States, but this also represents an opportunity for Canadian business and governments to forge stronger ties in various areas. The IMF expects a quick improvement in 2018 while other forecasters indicate it may take longer. Mexico is the third-highest import supplier to Canada, providing as much merchandise as Germany and Japan combined, and its products are crucial for several of Canada’s key industries: automotive, electric and electronic machinery, and mechanical machinery.

Economic growth in the eurozone pleasantly surprised, coming in at 2.3 percent—the best performance since the Great Recession. Its political risks certainly look less threatening than in 2016, and current projections call for an acceleration to 2.4-percent growth in 2018. Germany and Spain saw strong economic performances in 2017; these were likely their peak numbers this cycle, as growth is expected to moderate. The United Kingdom is projected to slow down to 1.6 percent in 2018, affected by continuing uncertainty surrounding Brexit, high inflation and strengthening currency. Canada’s historical commercial association with this region became stronger than ever with the provisional application of the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). It is now in force and is replete with excellent opportunities for Canadian businesses and consumers, especially in the area of services.

Emerging Asia remained the growth champion among the world’s regions. China’s economy continued its transition from investment-based to domestically driven growth; it also pledged to tackle advanced economic issues such as pollution and anti-poverty measures, while not skipping a beat in the growth department. China’s economy expanded 6.9 percent in 2017, faster than planned, and will maintain a strong pace in the short term. Canada continues to tighten commercial ties with China, including the talks on a potential free trade agreement. India is expected to continue on its growth path that is to peak around 8 percent before sloping down gently. Throughout this region, dynamic economies are specializing as large export platforms in electrical and electronic machinery, apparel, services and other areas, and could be excellent partners for Canadian businesses and foreign affiliates.

Canada’s economy recorded excellent growth in 2017, expanding by 3.0 percent. This strongest performance in six years benefited from the cyclical recovery in manufacturing and trade that began in mid-2016 across the developed economies. Canada’s economy added nearly 340,000 new jobs in 2017, bringing the labour market close to the equilibrium and reducing unemployment from 6.9 percent to 5.8 percent at year-end. With inflation stable, the economy is now operating close to its capacity. The resource sector continues to benefit from a progressive upturn in commodity prices, and the existing federal stimulus is expected to be supplemented by additional fiscal expansion in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec. Most of 2017 growth was realized during the first two quarters of the year, when it reached the scorching pace of 4.0 percent and 4.4 percent, respectively; it returned closer to potential growth with 1.5 percent in the third and 1.7 percent in the fourth quarter. Growth performance is expected to moderate to 2.1 percent in 2018 and to 2.0 percent in 2019. The Canadian dollar spent most of the year just below the US 80¢ mark. Over the course of the year, the loonie appreciated in value against the U.S. dollar and the Japanese yen, but depreciated against the European euro and the British pound.

The consequences of the shift in commodity prices reverberated through Canada’s trade during the year. Overall export prices rose 22.7 percent in the energy sector and 4.4 percent overall; meanwhile, the price index of Canada’s imports rose only 1.1 percent. The result was a substantial improvement in Canada’s terms of trade index, which rose from 91.6 in 2016 to 94.3 in 2017. Nevertheless, this value of the index is still historically low (third-lowest in the past 11 years). These changing terms of trade sent exports of resources and resource-based goods soaring—in particular, energy products, metal ores and minerals, and metal and mineral products; meanwhile, the strengthening Canadian dollar and relative prices rolled back exports in the manufacturing sectors—particularly automotive products and consumer goods. Canada’s overall trade deficit in goods narrowed, but that was nearly offset by a greater deficit in services trade due to the expanding travel and transportation services deficit. As a result of these and other developments, Canada’s current account deficit narrowed somewhat, declining from $65.4 billion in 2016 to $63.9 billion in 2017.

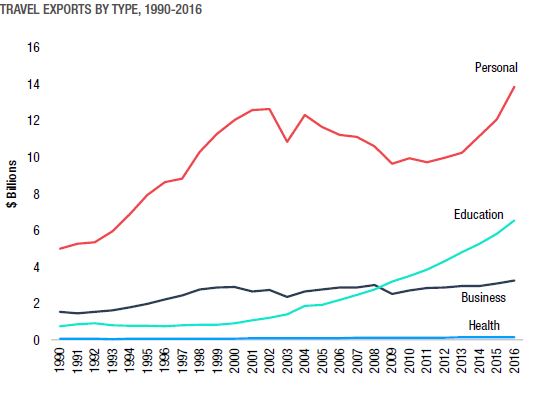

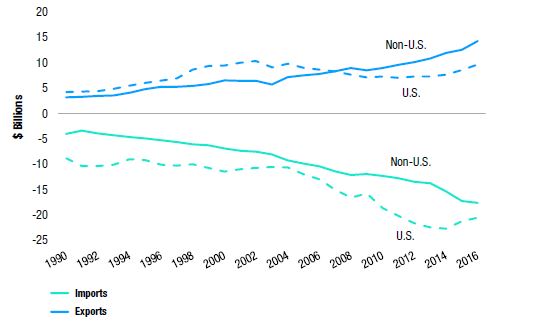

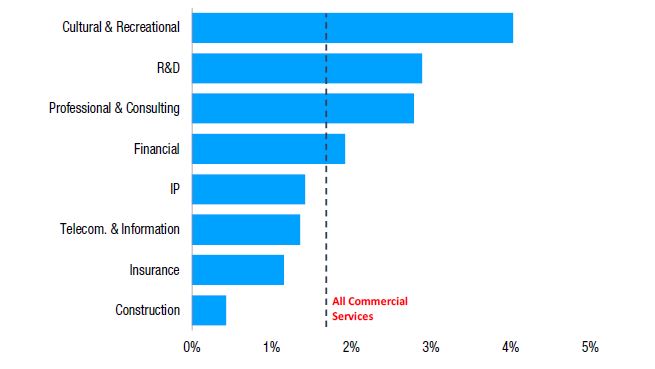

The volume of exports of goods increased 1.0 percent while the volume of imports expanded 3.6 percent. Nominal values of goods exports increased by 5.4 percent, strongly supported by prices, while nominal values of goods imports increased by 4.8 percent, partly supported by prices. Exports of services rose 3.6 percent, with imports growing 4.3 percent. Exports of commercial services grew just 0.7 percent in 2017, primarily due to a contraction in exports of financial services. Commercial services have run a surplus for 15 years (starting in 2003), but after declining for several years it has now shrunk to just $0.9 billion. Trade in services with the United States was perfectly balanced, with 54.5 percent of Canada’s exports going to the United States and 54.5 percent of its imports arriving from there. Of note was the high growth of 20.3 percent in Canada’s travel exports to non-OECD destinations, which could indicate a further strengthening in education, immigration and business travel to Canada from those countries.

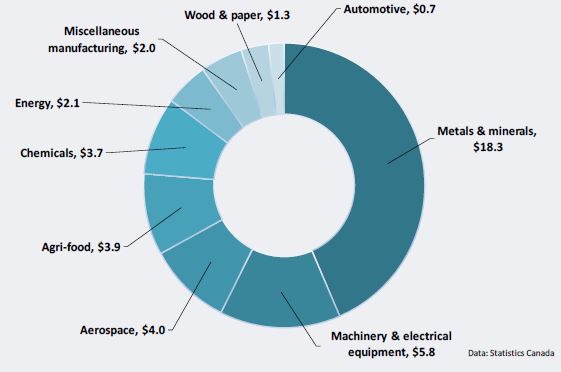

Detailed examination of Canada’s merchandise trade shows substantial growth in both exports (up 5.6 percent, or $29.2 billion) and imports (up 5.2 percent, or $27.8 billion). Exports reached an all-time high of $546.7 billion, and so did imports with $561.1 billion. Stronger energy export revenues (up 33.1 percent) were behind the rising exports; volumes also contributed for exports of all energy components to the United States, which was the destination for 91.1 percent of Canada’s energy exports. Notably, the four next top destinations for Canada’s energy exports were all in Asia; exports to each grew by over 50 percent, and the main energy product exported to all of these (Japan, South Korea, China and India) was coal.

The proportion of exports destined for the United States declined for the third consecutive year, reaching 76.0 percent of the total. Nevertheless, there was no increase in overall export diversification, as the share of Canadian exports for the top 10 destinations remained stable at 90.8 percent. The U.S. import share decreased 0.8 percentage point to 51.3 percent, which led to an overall increase in diversification for the top 10 destinations, as their share fell from 83.7 percent in 2016 to 83.3 percent in 2017. Exports to China, Japan and South Korea saw double-digit growth; Latvia was the highest-growing major export destination with 129.7-percent growth. Imports from China and Japan grew by double digits also.

Among notable trade developments, automotive exports declined by 4.9 percent, partly explained by the increased domestic consumption, production losses and interruptions. Exports of mechanical machinery and equipment grew 5.7 percent, mostly to the United States, and aluminum exports soared by 19.0 percent. After a long and sustained growth of at least five years, exports of pharmaceutical products stumbled in 2017, losing over a quarter of their value.

Global FDI flows declined to US$1.5 trillion in 2017, after reaching in 2015 their highest level since the global crisis. FDI inflows into developed economies decreased 27.0 percent during the year (and by one-third into North America) and accounted for 53.4 percent of the total, while inflows into developing economies rose slightly in 2017. Cross-border M&A contracted by 23 percent, mostly due to lower activity in developed countries; global greenfield FDI also declined.

FDI inflows into Canada declined by 36.4 percent in 2017, to $31.5 billion. Inflows from the United States dropped by 14.4 percent, while inflows from the rest of the world dropped by 63.0 percent. The overall reduction in investment flows was due to a combination of sharp overall declines in global FDI flows (particularly in developed countries, particularly in North America) and large ownership changes of oil sands assets from foreign to Canadian hands (divestment). Foreign inflows also decreased in management of companies and enterprises, as well as into finance and insurance and other industries, but almost doubled in manufacturing.

The stock of foreign investment in Canada rose 1.9 percent to $824.0 billion, with the proportion of that stock originating in the United States at 49.1 percent. While the manufacturing sector and the management of companies and enterprises sector were the two largest overall FDI targets in 2017, FDI stock increased considerably in finance and insurance, wholesale trade, transportation and warehousing and real estate and rental industries.

Canada’s direct investment abroad (CDIA) outflows increased for the seventh consecutive year in 2017 and nearly reached $100 billion. For the second straight year, CDIA flows increased considerably in trade and transportation, which accounted for over half of total outflows. Flows also increased in management of companies and enterprises and finance and insurance; a greater share of flows went to the United States than usual. Canada’s stock of investments abroad also rose in 2017, with the appreciation of the Canadian dollar offsetting some of the activity, and reached $1.1 trillion. Canada’s net direct investment position expanded by $22.1 billion in 2017, to the highest surplus on record ($297.1 billion).

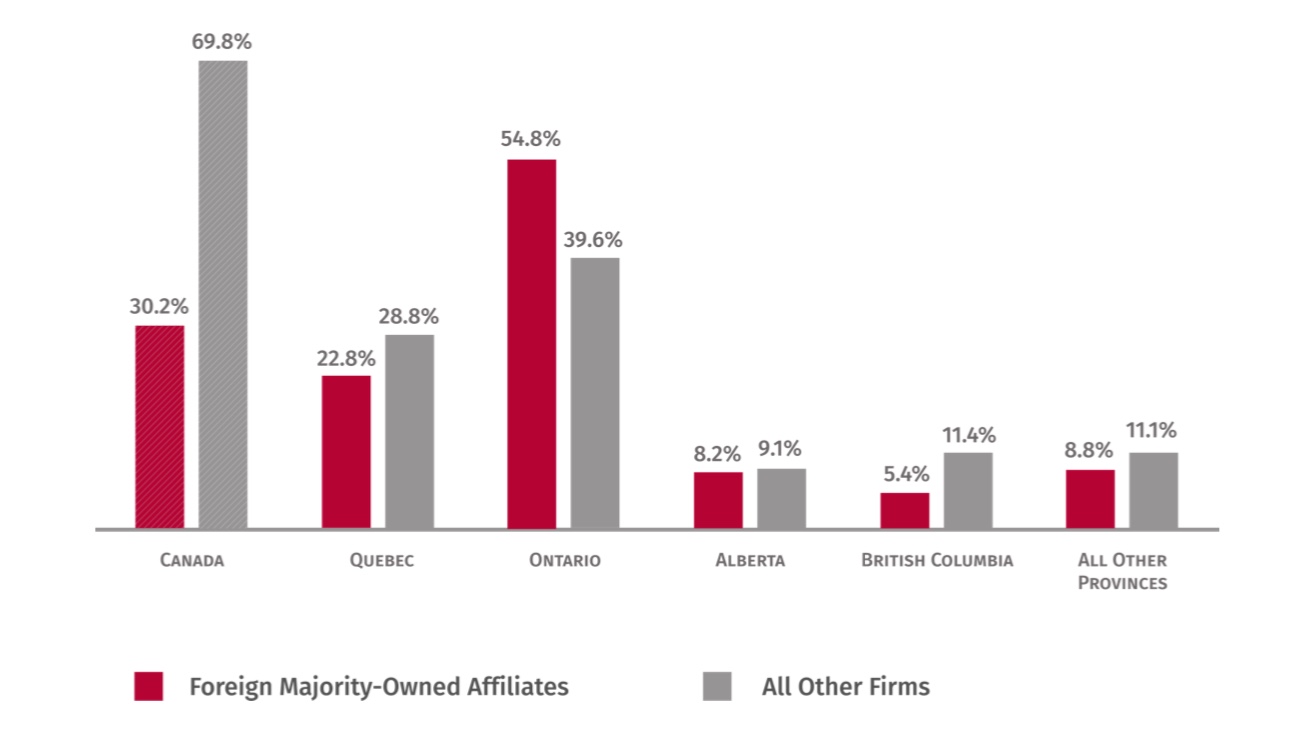

Foreign affiliates continued to be a significant part of Canadian economy, accounting for over half of Canada’s total merchandise trade.Footnote 3 These also accounted for 17.2 percent of Canada’s corporate assets, 27.1 percent of total operating revenues, employed 1.9 million Canadians and 34.5 percent of total R&D conducted in Canada. Meanwhile, Canadian foreign affiliates abroad sold more goods and services than was generated by Canada’s conventional exports, helping their Canadian parent firms stay competitive, gain access to technology and other inputs, and concentrate on headquarters activities.

Special Feature on Canada’s Services Trade Performance

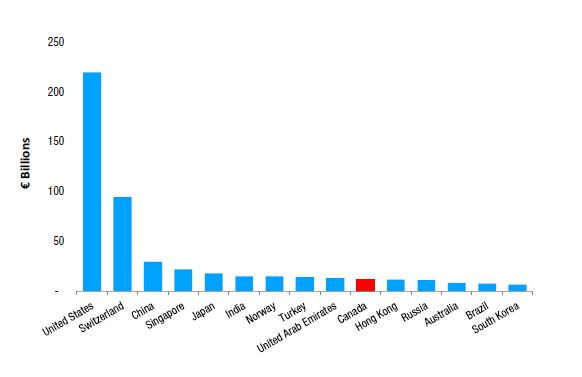

Services are becoming a more important share of Canadian exports, reaching 17.0 percent in 2017 and even more on a value-added basis, due to the high domestic content of services and to the indirect contribution of services to the value of goods exports. Yet services still account for a smaller share of Canadian exports than they do for most other advanced countries. Canada performs well in a number of services sectors that rely on skilled people and on innovation, most notably research and development, finance, professional services and education. Services are important for Canada’s international competitiveness more broadly as they are important inputs into the production process and help facilitate trade. Increasingly, they are also bundled alongside goods as part of a trend towards “servicification”, and in many cases may be the largest component of goods trade.

1. Global Economic and Trade PerformanceFootnote 1-1

Regions and Economies Overview

Infographic 1.1 Text Alternative

| Developed Economies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Value (US$B) | Share (%) | Growth (%) | |

| North America | 2,377 | 13.8 | 7.3 |

| Mexico | 409 | 2.4 | 9.5 |

| Canada | 421 | 2.4 | 7.8 |

| United States | 1,547 | 9.0 | 6.6 |

| Europe | 6,501 | 37.8 | 9.3 |

| Germany | 1,448 | 8.4 | 8.5 |

| France | 535 | 3.1 | 6.7 |

| United Kingdom | 445 | 2.6 | 8.6 |

| Developing Economies | |||

| Asia | 5,842 | 34.0 | 10.7 |

| Japan | 698 | 4.1 | 8.3 |

| China | 2,263 | 13.2 | 7.9 |

| India | 298 | 1.7 | 13.0 |

| South and Central America | 583 | 3.4 | 13.0 |

| Africa | 417 | 2.4 | 18.3 |

Infographic 1.2 Text Alternative

| Developed Economies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Value (US$B) | Share (%) | Growth (%) | |

| North America | 3,285 | 18.7 | 7.3 |

| Mexico | 432 | 2.5 | 8.7 |

| Canada | 442 | 2.5 | 7.0 |

| United States | 2,409 | 13.7 | 7.1 |

| Europe | 6,521 | 37.1 | 9.9 |

| Germany | 1,167 | 6.6 | 10.5 |

| France | 625 | 3.6 | 9.2 |

| United Kingdom | 644 | 3.7 | 1.2 |

| Developing Economies | |||

| Asia | 5,541 | 31.5 | 15.3 |

| Japan | 672 | 3.8 | 10.6 |

| China | 1,842 | 10.5 | 16.0 |

| India | 447 | 2.5 | 23.8 |

| South and Central America | 579 | 3.3 | 7.8 |

| Africa | 534 | 3.0 | 7.8 |

Infographic 1.3 Text Alternative

| Developed Economies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Value (US$B) | Share (%) | Growth (%) | |

| North America | 876 | 16.7 | 4.2 |

| Mexico | 27 | 0.5 | 10.1 |

| Canada | 86 | 1.6 | 5.8 |

| United States | 762 | 14.5 | 3.8 |

| Europe | 2,499 | 47.6 | 8.5 |

| Germany | 296 | 5.6 | 7.0 |

| France | 249 | 4.7 | 5.5 |

| United Kingdom | 354 | 6.7 | 4.9 |

| Developing Economies | |||

| Asia | 1,321 | 25.2 | 7.1 |

| Japan | 180 | 3.4 | 6.7 |

| China | 223 | 4.3 | 8.7 |

| India | 179 | 3.4 | 11.0 |

| South and Central America | 155 | 3.0 | 6.8 |

| Africa | - | - | - |

Infographic 1.4 Text Alternative

| Developed Economies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Value (US$B) | Share (%) | Growth (%) | |

| North America | 659 | 13.0 | 6.9 |

| Mexico | 37 | 0.7 | 9.9 |

| Canada | 105 | 2.1 | 6.5 |

| United States | 516 | 10.2 | 6.8 |

| Europe | 2,139 | 42.2 | 5.9 |

| Germany | 319 | 6.3 | 5.2 |

| France | 244 | 4.8 | 3.4 |

| United Kingdom | 218 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

| Developing Economies | |||

| Asia | 1,514 | 29.9 | 5.5 |

| Japan | 189 | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| China | 464 | 9.1 | 3.3 |

| India | 150 | 3.0 | 13.1 |

| South and Central America | 180 | 3.5 | 8.5 |

| Africa | - | - | - |

Infographic 1.5 Text Alternative

| Developed Economies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Value (US$B) | Share (%) | Growth (%) | |

| North America | 330 | 21.7 | -33.2 |

| Europe | 370 | 24.4 | -26.0 |

| Developing Economies | |||

| Asia | 459 | 30.2 | 2.5 |

| South and Central America | 143 | 9.4 | 2.9 |

| Africa | 49 | 3.2 | -2.0 |

The Great Recession struck almost a decade ago, but until 2016 the recovery from it was delayed, incomplete and desynchronized. In the second half of 2016 a widespread cyclical pickup of multiple indicators finally began, and by 2017 developed into a global recovery in manufacturing, trade and investment across the world. Economic growth in the last year exceeded most expectations. Business and consumer confidence, strong investment and generally favourable financial, fiscal and monetary conditions have mutually reinforced each other and built a great deal of momentum that will not be easy to quench. Global trade has been buoyed as a result, rebounding in both volume and values on the scale of the early post-recession years (2010-2011). Commodity prices have continued pushing upward from the lows of early 2016, now more firmly based on higher consumer demand, strengthening the balances of commodity exporters in the process. If the pace of expansion could be kept up for a few more years, the world would have a Great Recovery to match the Great Recession.

Alas, the prospects of that are slim. The above-trend growth is rapidly drawing the post-recession slack out of the system. The strings of the labour markets are being pulled ever more firmly across the developed world, the central banks are tightening warily, listening to the first signs of the incipient inflation pressures, and the business pundits across the world are back to forecasting the date of the next recession. Sometime in 2018, the excess growth in most developed countries is expected to begin moderating and start approaching potential growth numbers – which haven’t grown any prettier while the world dealt with the legacy of the Great Recession.

While commodity prices have continued pushing upward due to higher consumer demand, growth in most developed countries is expected to moderate

Demographics dictate bland performances under 2 percent, and it is to the Sphinx of technology that we look to break the deadlock, but its promises are as ambiguous as its riddles. Yet if the upside potential failed to increase, the downside risks have certainly swelled. Never has the rules-based trading system been under such strain as in 2017, and things are expected to get worse in 2018 before they can get better. Geopolitical tensions and tighter hold on power by the world’s many autocratic regimes point in the same direction, and it may be some time before the setting sun of the economic growth of 2017 across the world is approached in brilliance once again.

Following the upswing that began in the previous year, the world economy grew 3.2 percent in real terms during 2017 (aggregate on the basis of market exchange rates).Footnote 1-2 This was a major acceleration from the 2.5-percent growth in 2016 and the fastest that the world economy has expanded since 2010. In many areas, economic performance during 2017 exceeded expectations – in particular the eurozone, Japan, the United States and China. The two key drivers of the strengthening in global growth during the year were the recovery in investment spending in advanced economies and the end of investment contraction in commodity-exporting economies. Strong momentum, market and investor confidence, favourable financial conditions and a partial recovery in commodity prices fuel the expectations of an even stronger growth in the short term.

The world economy grew 3.2 percent with two key drivers of global growth being the recovery in investment spending in advanced economies and the end of investment contraction in commodity-exporting economies

Figure 1-1

Real GDP Growth in Major Economies, 2012-17

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 380-0064

Figure 1-1 Text Alternative

| Country | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 1.93 | 3.01 | 0.51 | -3.55 | -3.47 | 0.98 |

| Canada | 1.75 | 2.48 | 2.86 | 1.00 | 1.41 | 3.00 |

| China | 7.90 | 7.80 | 7.30 | 6.90 | 6.72 | 6.86 |

| Germany | 0.69 | 0.60 | 1.93 | 1.50 | 1.86 | 2.51 |

| India | 5.46 | 6.39 | 7.41 | 8.16 | 7.11 | 6.74 |

| Japan | 1.50 | 2.00 | 0.38 | 1.35 | 0.94 | 1.71 |

| France | 0.18 | 0.58 | 0.95 | 1.07 | 1.19 | 1.85 |

| United States | 2.22 | 1.68 | 2.57 | 2.86 | 1.49 | 2.27 |

| World | 3.52 | 3.47 | 3.58 | 3.45 | 3.23 | 3.76 |

Preliminary estimates indicate that global foreign direct investment (FDI) inflowsFootnote 1-3 decreased considerably in 2017, after reaching in 2015 their highest level since the start of the global crisis. FDI inflows targeting developed economies fell by over a quarter, with inflows into North America dropping by one-third. FDI inflows to developing economies increased marginally. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A) contracted, mostly due to lower activity in developed countries; global greenfield FDI also declined.

Overview and Prospects for the Global Economy

Aggregate Growth Trends

In purchasing-power parity (PPP)-adjusted terms, world growth accelerated to 3.8 percent in 2017, which was 0.5 percentage point faster than in the previous year. Growth in the advanced economies accelerated by 0.6 percentage point relative to 2016 to reach 2.3 percent, and the increase was due almost entirely to investment spending. This process was braced by generally accommodative monetary policy, stronger balance sheets and improved confidence. Strengthening investment brought about a strong recovery in global trade with large exporters such as Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States contributing significantly to it.

Most of the advanced economies were characterized by still-low core inflation, but edging up due to rising demand. The United Kingdom, where core inflation is still above the Bank of England’s target, is the single exception. Continued weakness in real wage growth across these economies points to some slack remaining in the labour markets, although there are signs of labour market firming in the United States. The cycle of monetary tightening is under way in most advanced economies, though overall it is still in a broadly stimulative mode. Output gaps are now closing faster than expected, and the economic growth is lining up with the estimated potential growth. The U.S. dollar has weakened modestly in real effective terms in the second half of 2017, and the euro has strengthened, while the Japanese yen remained broadly stable.

Figure 1-2

PPP-Adjusted Growth by Major Regions,

2014-2017 and Forecast 2018-2019

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 380-0064

Figure 1-2 Text Alternative

| Year | World | Advanced | Developing economies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 3.58 | 2.09 | 4.70 |

| 2015 | 3.45 | 2.30 | 4.30 |

| 2016 | 3.23 | 1.67 | 4.36 |

| 2017 | 3.76 | 2.34 | 4.76 |

| 2018 | 3.94 | 2.48 | 4.94 |

| 2019 | 3.94 | 2.22 | 5.10 |

| Regions (PPP aggregates) | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Advanced Economies | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| Eurozone | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.0 |

| Developing Economies | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.1 |

| Developing Asia | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.6 |

| Emerging Europe | 5.8 | 4.3 | 3.7 |

| CIS | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.8 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 2.6 | 3.4 | 3.7 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 2.8 | 3.4 | 3.7 |

| Countries (market-based aggregates) | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Canada | 3.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| United States | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.7 |

| United Kingdom | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| Japan | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| France | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Germany | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.0 |

| Italy | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Spain | 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.2 |

| China | 6.9 | 6.6 | 6.4 |

| India | 6.7 | 7.4 | 7.8 |

| Russia | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| Brazil | 1.0 | 2.3 | 2.5 |

| Mexico | 2.0 | 2.3 | 3.0 |

| Nigeria | 0.8 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| South Africa | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

Source: WTO Press Release, April 2018

Growth in the emerging and developing economies finally picked up after failing to grow substantially for six consecutive years, up 0.4 percentage point to 4.8 percent. As usual, performance was more uneven among this group, and the composition of growth varied greatly. Strong growth in emerging Asia continued, with China and India drawing strength from net exports and strong private consumption, while cutting back their investment growth. Among the rest of the group, on the contrary (particularly among the commodity-exporting countries), the investment effects were the main positive contributors. Fixed investment stopped contracting in Brazil and Russia as well as several commodity exporters. Growth in inventory investment was also an important growth factor, while a recovery in imports among commodity exporters helped private consumption recover, but also made net exports the largest drag on economic growth in the emerging and developing economies. Currencies were mostly stable or increasing against the U.S. dollar, helping to keep the core inflation low in Brazil, Russia and China. On the other hand, core inflation has risen in India and remained high in the Middle East and Africa. Financial conditions remained generally supportive, with monetary policy easing further in Brazil and Russia and equity markets generally strengthening.

Economic Growth and Outlook: Major Countries

The United States’ economy grew 2.3 percent in 2017, rebounding from the sub-par 1.5-percent growth of 2016, its weakest economic performance since 2009. Private consumption, non-residential fixed investment, and exports made significant positive contributions to the increase in real GDP in 2017. The acceleration in real GDP from 2016 to 2017 reflected upturns in nonresidential fixed investment and in exports and a smaller decrease in private inventory investment. These movements were partly offset by decelerations in residential fixed investment and in state and local government spending. Imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, accelerated.

Given that performance, growth forecasts for the United States have been revised upward. Higher projected external demand and the boost from recent fiscal policy stimulus are also positive factors. The IMF expects the U.S. economy to generate 2.9-percent growth in 2018 and 2.7-percent growth in 2019. Fiscal policy changes are expected to generate short-term growth gains until 2020, after which their effects will turn negative due to increasing fiscal deficit. This expected U.S. strength in the short term is welcome news for the Canadian economy.

The IMF expects the U.S. economy to generate 2.9-percent growth in 2018 and 2.7-percent growth in 2019 due to short-term growth generated by U.S. fiscal stimulus

Growth surprised on the positive side throughout the eurozone in 2017 and led to a considerable upside revision of the short-term IMF forecast as well. Germany has improved to 2.5-percent growth from 1.9 percent in 2016. France grew at 1.8 percent (up from 1.2 percent in 2016). The United Kingdom was the exception with a slight dip in growth to 1.8 percent in 2017, but even that is welcome news, given some of the Brexit expectations. The eurozone as a whole recorded a solid 2.3-percent growth in 2017, and that is expected to strengthen to 2.4 percent in 2018 before moderating to 2.0 percent in 2019. In Germany, growth should remain stable at 2.5 percent in 2018 and decelerate to 2.0 percent in 2019. France’s growth is expected to accelerate to 2.1 percent in 2018 before a slight slowdown to 2.0 percent in 2019. The United Kingdom is expected to continue slowing down in the short-term, to 1.6 percent in 2018 and to 1.5 percent in 2019, as business investment remains low due to uncertainty about the Brexit process and its results.

Japan also performed better than expected in 2017 and will continue to do so in the short run. Growth was 1.7 percent in 2017, surprising many observers. Expected to moderate to 1.2 percent in 2018 and to 0.9 percent in 2019, growth nevertheless remains above potential, which is weak due to unfavourable demographics leading to a declining labour force. Japan’s short-term strength is occasioned by better external demand prospects, a rebound in private investment and increased fiscal stimulus.

Many other advanced economies have reached a peak performance in 2017 (or, like New Zealand and Spain, in 2016) and are expected to slow down in the short term. That list includes Canada, Hong Kong, Ireland, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. Nevertheless, their growth numbers will remain respectable and in most cases above the long-term trend. In all of the Newly Industrialized Economies (NIEs) of Asia, growth in 2018 will slow down: in Hong Kong from 3.8 percent to 3.6 percent, in Taiwan from 2.8 percent to 1.9 percent, in Singapore from 3.6 percent to 2.9 percent, and in South Korea from 3.1 percent to 3.0 percent. The latter is expected to continue performing above trend in spite of international tensions over the Korean peninsula.

Among the developing economies, China continued to perform strongly with 6.9-percent growth in 2017 and is projected to slow down slightly: to 6.6 percent in 2018 and to 6.4 percent in 2019. Stronger external demand supported a slight upward revision of the forecast. Continued rebalancing from investment to consumption will bring the growth down to about 5.5 percent over the medium term, as policy support from credit growth and government policies is reduced and the social safety measures are strengthened. India’s growth of 6.7 percent in 2017 was below expectations due to implications of its currency exchange initiative, but a rebound to 7.4 percent is projected for 2018, rising to 7.8 percent by 2019. Private consumption growth is strong, and efficiency-improving reforms are under way. Broadly stable and strong growth of 5.3 percent was recorded in the ASEAN-5 economies; more of the same is expected for the region as the IMF forecast calls for 5.3-percent growth in 2018 and 5.4 percent in 2019.

Mexico has outperformed expectations with 2.0-percent expansion in 2017, and prospects are for further improvement. A more robust 2.3-percent GDP growth is expected in 2018, then rising to 3.0 percent in 2019 as the country benefits from the acceleration of the U.S. economy. The completion of a structural economic reform agenda is expected to maintain 3.0-percent growth in Mexico over the medium term. Brazil has emerged from a major recession to return to growth in 2017 at 1.0 percent. It is expected to continue accelerating up to 2.3 percent in 2018 and 2.5 percent in 2019 as private consumption and investment return to normal.

Argentina’s GDP grew 2.9 percent, but is projected to dip next year due to tighter fiscal and monetary policies, exacerbated by a drought affecting the country’s substantial agricultural sector

Activity in Argentina came in at 2.9 percent in 2017, but is projected to dip to 2.0 percent in 2018 as the effects of fiscal and monetary adjustments needed to curb inflation and reform public finances will be exacerbated by a drought that will affect the country’s substantial agricultural sector. Russia exited its recession with 1.5-percent growth in 2017, supported by stronger oil prices and looser monetary policy, and will grow at 1.7 percent in 2018, before headwinds and tightening sanctions depress economic activity to 1.5 percent over the medium term. Both Poland and Turkey are projected to grow above potential in 2018, at 4.1 percent and 4.4 percent respectively, before moderating to long-term potential in the medium term. Nigeria returned to positive growth, and growth is expected to be 2.1 percent in 2018 and 1.9 percent in 2019, while South Africa is also headed to improve its 1.3-percent growth of 2017 to 1.5 percent in 2018 and 1.7 percent in 2019.

The balance of the risks to the outlook has improved relative to the previous year due to solid gains and considerable momentum; risks are now two-sided and roughly balanced. There is a potential for positive surprises: strong confidence can boost investment and hiring plans, and labour markets may have greater slack than estimated, leading to a general increase in economic activity. Increases in investment could lead to a boost to productivity and unlock a pathway to higher potential growth in the future. At the same time, the downside risks include: uncertainty of the current geopolitical environment, risks of disruptions to global trade, financial vulnerabilities, political discord and climatic catastrophes.

Economic Growth and Outlook: Major Aggregates

Global GDP growth was recorded at 3.8 percent in 2017 (PPP-adjusted), soaring above 4 percent toward the end of the year, with strong support from investment activity. Improved performance for world growth is expected next year as financial conditions still remain supportive. According to the IMF, PPP-adjusted growth will rise to 3.9 percent for 2018 and 2019 (or, if calculated with market-based exchange rates, to 3.4 percent and 3.3 percent, respectively). The IMF forecasts improved performance in the short-term both from advanced economies, at 2.5 percent for 2018 and 2.2 percent for 2019, as well as from developing economies to 4.9 percent in 2018 and 5.1 percent in 2019. This growth is projected to soften in the medium term, as output gaps close and advanced economies return to their lacklustre potential output paths.

The advanced economies have been in a continued recovery mode ever since the Great Recession, which is now drawing to a definite close. Growth is peaking above potential to end the cycle, as normality is restored in labour and investment markets. Faster-than-expected closing of the output gaps and the upward revisions to the estimated potential growth account for the current growth spike. Beyond the short term, growth rates are expected to dip below pre-recession levels as the aging populations and shrinking labour forces in the advanced economies will act as a drag on expansion. Fiscal policy is expected to remain expansionary in 2018 and 2019, but turn mildly contractionary by 2020 and more so by 2023 when the front-loaded investment provisions of U.S. tax reform begin to expire. Monetary policy will remain very supportive in the eurozone and Japan, but will tighten faster than projected in the United States. Global financial conditions will continue to remain generally accommodative.

While the advanced economies have continued to recover ever since the Great Recession, growth rates are expected to dip below pre-recession levels as the populations age and the labour forces shrink

The emerging and developing economies have not seen an improvement in growth since 2010, but that came to an end last year as they expanded 4.8 percent, up from 4.4 percent in 2016. Growth continued to be strong in emerging and developing Asia and accelerated substantially in emerging Europe. Latin America and the Caribbean region left negative growth behind them, and sub-Saharan Africa accelerated as well; the only exception to the improvement trend was in the Middle East and North African (MENA) countries, whose growth in 2017 was just over half of the previous year’s pace. Commodity exporters had a better year after three years of weakness as commodity prices recovered substantially, owing to a general improvement in activity. The IMF commodity price index is expected to rise 11.9 percent in 2018 and then decrease about 3.7 percent in 2019. Beyond the short term, growth in emerging and developing economies is projected to stabilize at about 5 percent.

Emerging and developing Asia will remain the key engine of global growth, growing steadily at a 6.5-percent pace in 2018 and accelerating to 6.6 percent in 2019. Emerging Europe will slow down from its high current rates to 4.3 percent in 2018 and to 3.7 percent in 2019 as strong demand for exports from its eurozone neighbours and favourable financial conditions support activity. Recovery in commodity prices will be very welcome to Latin American and Caribbean economies and should propel them to growth of 2.0 percent in 2018 and 2.8 percent in 2019. MENA countries will also pick up their pace – to 3.4 percent in 2018 and 3.7 percent in 2019, with support from higher oil prices crucial to their prospects. Growth in sub-Saharan Africa is also projected to increase to 3.4 percent in 2018 and 3.7 percent in 2019, with commodity prices key to the growth.

Overview and Prospects for World Trade

World merchandise trade recorded its largest increase in six years as it expanded 4.7 percent in 2017 in real terms. This trade expansion follows on the heels of a very weak 1.8-percent growth in 2016, when trade growth lagged behind the growth in real world output. According to the WTO, this large acceleration in trade growth was due to stronger than expected economic growth across the globe, with strong investment Footnote 1-4 numbers, private consumption and supportive fiscal as well as financial conditions. The renewed strength of world trade volumes should persist in the short term, with its pace cooling off slightly to 4.4 percent by 2018 and to 4.0 percent in 2019.

World merchandise trade recorded its largest increase in six years as it expanded 4.7 percent; the strength of world trade volumes should persist in the short term and cool off in the medium term

At the same time, there are grave risks to this forecast as the heightened trade tensions and uncertainty about the major economies’ commitment to existing rules-based architecture begin to threaten business confidence, affect investment decisions and undermine the robustness of current global economic growth. This outlook is thus dependent on the governments continuing to manage global trade through collective action and employing appropriate trade, monetary and fiscal policies.

The largest trade volume gains in 2017 were recorded on the import side in developing economies; real import growth soared to 7.2 percent after a tepid 1.9-percent performance in 2016. Meanwhile, developed economies’ real imports grew a less spectacular 3.1 percent in 2017 after recording 2.0-percent growth the year before. Real merchandise exports grew 5.7 percent in developing economies in 2017 and 3.5 percent in developed economies, several percentage points above their 2016 performance. The dynamics of growth were also different: while the developing economies achieved higher overall import growth, it was the developed economies that had more momentum at the end of the year, as higher economic growth in these countries took hold.

The recovery in export trade volumes was broad across the world’s regions as exports from North America, South and Central America and the Caribbean (SCAC), Europe and Asia all grew faster

The recovery in export trade volumes was broad across the world’s regions in 2017. Exports from North America, South and Central America and the Caribbean (SCAC), Europe and Asia all grew faster than in 2016. Asia was the leader with 6.7-percent exports growth, followed by North America at 4.2 percent. Europe’s exports also picked up considerably, from 1.1 percent in 2016 to 3.5 percent in 2017. On the import side, Asia also led with 9.6-percent volume growth, with North America and SCAC both posting a substantial 4.0-percent growth – the former after a near-zero growth in 2016, the latter on the heels of a 6.8-percent contraction in real imports in the same year.

Nominal world imports measured in U.S. dollars expanded 10.7 percent in 2017 after two years of declines, reaching US$17.6 trillion. The stability of the U.S. dollar versus a broad basket of currencies, in spite of the commodity price increases, contributed to this increase. China has once again become the greatest merchandise trading nation, recording US$4.1 trillion in total trade and passing the United States with US$4.0 trillion. Europe remained the greatest trading continent with US$13.0 trillion in total trade, ahead of Asia with US$11.4 trillion. World imports of commercial services also increased in value considerably in 2017 (volume statistics for services are not available), up 6.5 percent to US$5.1 trillion.

The WTO forecast is for a gradual moderation in merchandise trade growth in 2018 and 2019, but projects a strong performance in the short term. Optimism is supported by the recent strength in leading trade indicators such as the container port throughput index and global export orders. On the other hand, the continually swelling tide of anti-trade sentiment and trade-restricting measures carries significant risks to the outlook. If the current GDP growth forecasts are realized, trade volumes will expand by 4.4 percent in 2018; developing economies will see import growth of 4.8 percent and export growth of 5.4 percent, while developed economies will expand their imports by 4.1 percent and their exports by 3.8 percent. A slowdown to 4.0 percent in global trade volume growth in 2019 will affect these estimates roughly in proportion.

Merchandise Exports

In nominal terms, the CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) was the surprising world leader in exports growth in 2017 among the world’s regions, recording a 24.4-percent increase from the previous year. This was partly due to higher energy prices, which buoyed a large proportion of the region’s exports, and partly to lower trade levels of 2016 due to a recession in Russia (whose exports expanded by over a quarter in 2017). Commodity price increases also occasioned a strong growth in value of Africa’s exports, which were up 18.3 percent, and those from the Middle East, up 18.0 percent. The SCAC region also benefited from higher commodity prices with 13.0-percent growth as well as from the end of a recession in Brazil (whose exports expanded by 17.5 percent in 2017). Asia’s nominal exports grew 10.7 percent, with India leading the ranks at 13.0-percent growth and NIEs not far behind with a combined 12.6-percent growth performance. Exports from Europe expanded to 9.3 percent with a strong performance from Italy (up 9.6 percent), the United Kingdom (up 8.6 percent) and Germany (up 8.5 percent). North America’s exports grew at the slowest pace among the world’s regions (up 7.3 percent) with Mexico in the lead at 9.5 percent. Europe remained the globe’s greatest exporter with a 37.8-percent share, followed by Asia with 34.0 percent and the other regions far behind.

| Value US$B | Share (%) | Growth (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| US$B | (%) | (%) | |

| World | 17,198 | 100.0 | 10.7 |

| North America | 2,377 | 13.8 | 7.3 |

| United States | 1,547 | 9.0 | 6.6 |

| Canada | 421 | 2.4 | 7.8 |

| Mexico | 409 | 2.4 | 9.5 |

| South & Central America | 583 | 3.4 | 13.0 |

| Brazil | 218 | 1.3 | 17.5 |

| Europe | 6,501 | 37.8 | 9.3 |

| EU-28 | 5,904 | 34.3 | 9.7 |

| Germany | 1,448 | 8.4 | 8.5 |

| France | 535 | 3.1 | 6.7 |

| United Kingdom | 445 | 2.6 | 8.6 |

| Italy | 506 | 2.9 | 9.6 |

| CIS | 518 | 3.0 | 24.4 |

| Russia | 353 | 2.1 | 25.3 |

| Africa | 417 | 2.4 | 18.3 |

| Middle East | 961 | 5.6 | 18.0 |

| Asia | 5,842 | 34.0 | 10.7 |

| China | 2,263 | 13.2 | 7.9 |

| Japan | 698 | 4.1 | 8.3 |

| India | 298 | 1.7 | 13.0 |

| NIEs | 1,283 | 7.5 | 12.6 |

Source: WTO Press Release, April 2018

Merchandise Imports

In nominal terms, world merchandise imports also rose 10.7 percent on the year to reach US$17.6 trillion. Import values were up across the globe, but the CIS again was the fastest-growing region, with 20.8-percent increase in import value. This was mainly due to Russia coming out of the recession and the greater value of its energy-intensive exports (Russia’s imports were up 24.1 percent in 2017). Asia also recorded a big jump in its imports, which expanded 15.3 percent. India was the leader again with a 23.8-percent import increase, followed by China with 16.0 percent.

Nominal import growth in most other regions was clustered just short of 10 percent: Europe was third with 9.9 percent, Africa and SCAC regions next at 7.8 percent and North America at 7.3 percent (with Mexico again in the lead with 8.7-percent growth). Imports were stagnant in the Middle East, which was last among the regions with a tepid 1.1-percent growth performance.

| Value US$B | Share (%) | Growth (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 17,572 | 100.0 | 10.7 |

| North America | 3,285 | 18.7 | 7.3 |

| United States | 2,409 | 13.7 | 7.1 |

| Canada | 442 | 2.5 | 7.0 |

| Mexico | 432 | 2.5 | 8.7 |

| South & Central America | 579 | 3.3 | 7.8 |

| Brazil | 157 | 0.9 | 9.7 |

| Europe | 6,521 | 37.1 | 9.9 |

| EU-28 | 5,878 | 33.5 | 10.0 |

| Germany | 1,167 | 6.6 | 10.5 |

| France | 625 | 3.6 | 9.2 |

| United Kingdom | 644 | 3.7 | 1.2 |

| Italy | 453 | 2.6 | 11.2 |

| CIS | 402 | 2.3 | 20.8 |

| Russia | 238 | 1.4 | 24.1 |

| Africa | 534 | 3.0 | 7.8 |

| Middle East | 712 | 4.1 | 1.1 |

| Asia | 5,541 | 31.5 | 15.3 |

| China | 1,842 | 10.5 | 16.0 |

| Japan | 672 | 3.8 | 10.6 |

| India | 447 | 2.5 | 23.8 |

| NIEs | 1,203 | 6.8 | 13.7 |

Source: WTO Press Release, April 2018

Among the large economies, import expansions in Italy (up 11.2 percent), Germany (up 10.5 percent) Brazil (up 9.7 percent) and France (up 9.2 percent) are worth noting, as is the United Kingdom’s weak import growth of just 1.2 percent, mainly occasioned by the depreciation of its currency.

Europe remained the world’s leading importer, at 37.1 percent of the global trade, while Asia’s imports accounted for 31.5 percent of the total; together these two regions import well over two-thirds of the world’s merchandise. North America’s share was 18.7 percent, while all other regions together accounted for less than 13 percent of global imports.

Services Exports

After two years of languishing, nominal world services exports measured in U.S. dollars grew strongly in 2017, rising 7.4 percent to reach US$5.3 trillion. Transport services grew the fastest at 8.3 percent, and travel services were up 7.2 percent, while goods-related services Footnote 1-5 registered the slowest growth of all categories as their value increased 5.2 percent. The latter category was the best performer in the years 2015 and 2016.

On a regional basis, “other regions” (which includes Africa, the CIS and the Middle East) performed the best, recording 9.8-percent growth in service exports. Growth was particularly remarkable in Egypt (up 38.2 percent) and Russia (up 15.9 percent). Europe recorded the next-highest increase with 8.5-percent aggregate growth, reaching a US$2.5-trillion total. The Netherlands led this region with a 15.6-percent expansion while growth was slow in the United Kingdom at 4.9 percent. Asia was third-fastest in service exports growth, up 7.1 percent; India was in the lead again with 11.0-percent growth and China ahead of the average at 8.7 percent, while the NIEs recorded only a 2.1-percent increase.

Exports of services from SCAC countries were 6.8-percent higher than in 2016; Brazil’s expansion was only half as fast at 3.4 percent. North America registered the smallest increase of all regions, up 4.2 percent, with Mexico showing the largest growth at 10.1 percent and the United States the smallest at 3.8 percent. Canada’s services exports increased by 5.8 percent. Footnote 1-6

Europe continued to be the world’s leading provider of services, accounting for 47.6 percent of global value of exports, due largely to intra-EU trade in services. Asia ranked second, with just over a quarter of the global exports (US$1.3 trillion), while North America was third, with US$0.9 trillion – accounting for 16.7 percent of the global services exports in 2017.

| Value US$B | Share (%) | Growth (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 5,252 | 100.0 | 7.4 |

| North America | 876 | 16.7 | 4.2 |

| United States | 762 | 14.5 | 3.8 |

| Canada | 86 | 1.6 | 5.8 |

| Mexico | 27 | 0.5 | 10.1 |

| South & Central America | 155 | 3.0 | 6.8 |

| Brazil | 34 | 0.6 | 3.4 |

| Europe | 2,499 | 47.6 | 8.5 |

| EU-28 | 2,226 | 42.4 | 8.5 |

| Germany | 296 | 5.6 | 7.0 |

| United Kingdom | 354 | 6.7 | 4.9 |

| France | 249 | 4.7 | 5.5 |

| Netherlands | 216 | 4.1 | 15.6 |

| Asia | 1,321 | 25.2 | 7.1 |

| China | 226 | 4.3 | 8.7 |

| Japan | 180 | 3.4 | 6.7 |

| India | 179 | 3.4 | 11.0 |

| NIEs | 400 | 7.6 | 2.1 |

| Other Regions | 401 | 7.6 | 9.8 |

| Russia | 58 | 1.1 | 15.9 |

| Egypt | 19 | 0.4 | 38.2 |

| South Africa | 15 | 0.3 | 9.3 |

| United Arab Emirates | 70 | 1.3 | 7.5 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 380-0064

Services Imports

The total value of world services imports rose 6.5 percent to US$5.1 trillion in 2017. “Other regions” was the bestperforming import region; services imports expanded 10.3 percent, led by Russia’s increase of 18.8 percent despite some countries, like Egypt and the UAE, posting marginal growth rates. SCAC was the next-highest region of import growth with a combined increase of 8.5 percent. Brazil performed just below this average with 7.9-percent growth.

North America recorded next-highest import growth at 6.9 percent: Mexico led with 9.9-percent growth, followed by the United States at 6.8 percent, while Canada’s imports of services increased 6.5 percent. Footnote 1-7

Uncharacteristically, Europe and Asia found themselves at the back of the rankings with growth of 5.9 percent and 5.5 percent, respectively. The Netherlands led Europe with 14.7-percent growth, but the performances of France and the United Kingdom were weaker than the average. Among the large Asian countries, India’s performance of 13.1-percent services import growth was exceptional; the NIEs grew at the average pace of 5.5 percent, while China’s 3.3-percent growth fell far short of the average for the region.

Europe remained the largest importer of services, with 42.2 percent of the world’s imports in 2017, followed by Asia with 29.9 percent. North America’s import share equalled 13.0 percent, while Africa, the Middle East and the CIS combined equalled 11.4 percent of the total, significantly expanding their share.

| Value US$B | Share (%) | Growth (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 5,072 | 100.0 | 6.5 |

| North America | 659 | 13.0 | 6.9 |

| United States | 516 | 10.2 | 6.8 |

| Canada | 105 | 2.1 | 6.5 |

| Mexico | 37 | 0.7 | 9.9 |

| South & Central America | 180 | 3.5 | 8.5 |

| Brazil | 66 | 1.3 | 7.9 |

| Europe | 2,139 | 42.2 | 5.9 |

| EU-28 | 1,915 | 37.8 | 5.4 |

| Germany | 319 | 6.3 | 5.2 |

| United Kingdom | 218 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

| France | 244 | 4.8 | 3.4 |

| Netherlands | 211 | 4.2 | 14.7 |

| Asia | 1,514 | 29.9 | 5.5 |

| China | 464 | 9.1 | 3.3 |

| Japan | 189 | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| India | 150 | 3.0 | 13.1 |

| NIEs | 421 | 8.3 | 5.5 |

| Other Regions | 580 | 11.4 | 10.3 |

| Russia | 87 | 1.7 | 18.8 |

| Egypt | 16 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| South Africa | 16 | 0.3 | 7.5 |

| United Arab Emirates | 84 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

Source: WTO Press Release, April 2018

Overview of Global Foreign Direct Investment Flows

According to preliminary estimates from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), global FDI inflows decreased by 16.3 percent in 2017 to US$1.5 trillion. This was well below their peak of US$1.9 trillion in 2007.

FDI inflows to developed economies fell 27.0 percent to an estimated US$810 billion in 2017, accounting for a 53.4-percent share of world FDI inflows. North American inflows declined by 33.2 percent to US$330 billion. This was partly caused by the decline in cross-border M&A between Canada and the United States. Inflows into the United States decreased in 2017, yet the country remained the world’s largest recipient of inflows for the third year in a row with an estimated US$311 billion. Within the EU countries, inflows declined by 26.0 percent, accounting for just below one-quarter of global inflows. A significant portion of this decline can be attributed to lower FDI inflows into the United Kingdom, which experienced a 90-percent drop in 2017. Inward flows to Belgium, Spain and the Netherlands also fell. Germany was the highlight of developed economy inflows, which more than tripled in value (from US$10 billion to an estimated US$35 billion), and France experienced a significant increase in FDI flows, mainly due to a number of high value M&A deals.

| 2016 (US$B) | 2017 (US$B) | Growth (%) | Share (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World | 1,814 | 1,518 | -16 | 100.0 |

| Developed Economies | 1,109 | 810 | -27 | 53.4 |

| EU | 500 | 370 | -26 | 24.4 |

| North America | 494 | 330 | -33 | 21.7 |

| Developing Economies | 638 | 653 | 2 | 43.0 |

| Africa | 50 | 49 | -1 | 3.2 |

| Latin America & Caribbean | 139 | 143 | 3 | 9.4 |

| Developing Asia | 448 | 459 | 2 | 30.2 |

| Transition Economies] | 67 | 55 | -17 | 3.6 |

Source: UNCTAD, Investment Trends Monitor, April 2018

FDI inflows to developing economies grew 2.4 percent, to US$653 billion in 2017, accounting for 43.0 percent of global inflows. In Latin America and the Caribbean, flows increased by 2.9 percent to US$143 billion. Inflows to Africa registered a marginal decline of 2.0 percent to US$49 billion. In developing Asia, FDI inflows grew 2.5 percent to US$459 billion. Mainland China and Hong Kong were the second- and third-largest recipients of FDI, at US$144 billion and US$85 billion, respectively.

FDI inflows to transition economies decreased sharply in 2017, falling 17.9 percent from US$67 billion to US$55 billion. This was largely driven by a drop for the Russian Federation and lower inflows across most of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Cross-border M&A contracted by 23 percent to US$666 billion in 2017. The decline was driven by a decrease of 30 percent (to US$553 billion) in developed economies, while in developing economies the value of cross-border M&A increased by 44 percent (to US$100 billion). Worldwide greenfield FDI also decreased significantly, to US$571 billion.

Figure 1-3

Top Performing Trade Regions: Europe VS. Asia, 2017 (Estimated)

Figure 1.3 Text Alternative

| Europe | Asia | |

|---|---|---|

| Export Volume, Growth (%) | 3.5 | 6.7 |

| Import Volume, Growth (%) | 2.5 | 9.6 |

| Nominal Total Merchandise Trade (US$ Trillion) | 13.0 | 11.4 |

| Nominal Merchandise Exports (US$ Trillion) | 6.5 (+9.3% growth) | 5.8 (+10.7% growth) |

| Nominal Merchandise Imports (US$ Trillion) | 6.5 (+9.9% growth) | 5.5 (+15.3% growth) |

| Nominal Total Service Trade (US$ Trillion) | 4.6 | 2.8 |

| Nominal Service Exports (US$ Trillion) | 2.5 (+8.5% growth) | 1.3 (+7.1% growth) |

| Nominal Service Imports (US$ Trillion) | 2.1 (+5.9% growth) | 1.5 (+5.5% growth) |

2. Economic and Trade Developments: Regional and Country Overview

Infographic 2.1 Text Alternative

| Population (M) | GDP per Capita (US$) | GDP Growth (%) | Canadian Merchandise Exports (US$B) | Canadian Merchandise Imports (US$B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 325.9 | 59,531.6 | 2.3 | 319.5 (+7.3%) | 221.9 (+5.6%) |

| China | 1,390.1 | 8,643.1 | 6.9 | 18,200.3 (+15.0%) | 54,777.2 (+12.7%) |

| Mexico | 123.5 | 9,304.2 | 2.0 | 6,057.8 (+5.0%) | 27,353.8 (+9.1%) |

Infographic 2.2 Text Alternative

| Emerging Asia | |

|---|---|

| Population (M) | 3,574.9 |

| GDP Growth (%) | 6.5 |

| Canadian Merchandise Exports (US$M) | |

| Total | 26,282.2 (+14.6%) |

| Wood Pulp | 3,515.5 |

| Oil Seeds | 3,144.6 |

| Mineral Fuels | 1,635.4 |

| Cereals | 1,611.6 |

| Wood & Articles | 1,463.9 |

| Canadian Merchandise Imports (US$M) | |

| Total | 71,718.9 (+11.3%) |

| Electric Machinery & Equipment | 17,623.7 |

| Mechanical Machinery & Equipment | 11,903.1 |

| Knit Apparel & Accessories | 3,870.7 |

| Furniture | 3,850.4 |

| Non-Knit Apparel & Accessories | 3,399.4 |

Infographic 2.3 Text Alternative

| Eurozone | |

|---|---|

| Population (M) | 338.5 |

| GDP Growth (%) | 2.3 |

| Canadian Merchandise Exports (US$M) | |

| Total | 16,296.8 (+4.5%) |

| Ores | 2,195.1 |

| Mechanical Machinery & Equipment | 1,978.5 |

| Aircraft | 1,472.5 |

| Mineral Fuels | 1,327.9 |

| Precious Stones & Metals | 1,227.4 |

| Canadian Merchandise Imports (US$M) | |

| Total | 38,431.1 (+11.1%) |

| Mechanical Machinery & Equipment | 6,855.8 |

| Automotive Products | 5,587.5 |

| Pharmaceuticals | 4,135.1 |

| Mineral Fuels | 2,324.2 |

| Electric Machinery & Equipment | 2,310.8 |

Infographic 2.4 Text Alternative

| Latin America and the Caribbean | |

|---|---|

| Population (M) | 619.8 |

| GDP Growth (%) | 1.3 |

| Canadian Merchandise Exports (US$M) | |

| Total | 11,688.0 (+4.6%) |

| Mechanical Machinery & Equipment | 1,319.7 |

| Cereals | 1,137.8 |

| Automotive Products | 1,099.0 |

| Mineral Fuels | 801.6 |

| Oil Seeds | 743.6 |

| Canadian Merchandise Imports (US$M) | |

| Total | 40,192.0 (+8.9%) |

| Automotive Products | 9,339.8 |

| Electric Machinery & Equipment | 5,390.1 |

| Mechanical Machinery & Equipment | 4,414.3 |

| Precious Stones & Metals | 3,363.0 |

| Fruits & Nuts | 1,768.1 |

Strong economic performance with the fastest growth since 2011 buoyed global investment and trade in 2017. Activity was particularly impressive in the eurozone, Japan, China and the United States, all of which exceeded expectations last year. As an open economy, Canada is strongly affected by events in other economies and global trends. For example, in 2017, the enactment of a new budget in the United States affected the flow of foreign investment into Canada, and tensions in the Middle East have supported oil prices, thus positively affecting Canada’s terms of trade. Since Canada’s trade is fairly strongly concentrated, it may be particularly affected by events in a handful of key countries and regions. While the previous chapter briefly dealt with important global influences, this chapter describes the economic situation in Canada’s most important trading partners – the United States, China and Mexico – and in the key regions for Canada’s international activities – emerging Asia, the eurozone and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

Many risks and policy challenges facing economies in 2017 are widely shared. A more interconnected world should make it easier to work together for the common good, but that is not what is observed at the moment. Ensuring stable external demand, fostering business and consumer confidence, raising productivity, improving income distribution and preserving a rules-based system of international exchange are the necessary conditions of prosperity for most countries. Yet when there is no domestic agreement on the solutions for these standard economic problems, political deadlock ensues and aggravates them. International institutions have long been a source of economic guidance, but currently there is a lack of worldwide agreement on their future role. Thus the whole multilateral trading and investment system reflecting the post-WWII consensus is in question, representing a threat to economic stability as we know it.

Advanced economies have an additional set of their own peculiar issues: the effect of their aging populations on labour force and productivity, income inequality, and sharing economic influence with emerging powers. The emerging economies have the advantage of a rosier labour force picture (with an important exception of China), grappling instead with challenges of continuous economic and social reforms, infrastructure, labour standards, human rights, pollution and governance institutions.

Considering the above picture, the key regions for Canada’s commercial policy offer greater challenges and greater opportunities than before. While the paramount importance of the United States to Canada’s economy will not change, other regions and countries may become more or less crucial for Canada – often depending on shared values and treaties that link it to these nations. In the coming years, the well-established links with the eurozone should expand further, as the implementation of the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) occurs. For similar reasons, proximity to and engagement with LAC, and particularly Mexico, are to be expected, especially given the potential barriers in their economic relationship with the United States.

Emerging Asia continues to be a global growth leader, with China and India still the lands of peerless opportunities

Emerging Asia continues to be a global growth leader and cannot be ignored, with China and India still the lands of peerless opportunities; the trade talks with China are an important step in taking advantage of these opportunities. This chapter provides a brief overview of the most important facets of economic and trade developments in these countries and regions.

Country Overview

United States

Annual economic growth in the United States accelerated by the better part of a percentage point, from 1.5 percent in 2016 to 2.3 percent in 2017. This real GDP growth primarily reflected positive contributions from household expenditures, non-residential fixed investment, and exports. Government spending made a near-zero contribution. These contributions were partly offset by negative contributions from private inventory investment and imports. Compared with the previous year, the acceleration in real GDP reflected upturns in non-residential fixed investment and in exports. These positive contributing factors were partly offset by decelerations in residential fixed investment and in state and local government spending, as well as the acceleration in imports.

Growth in U.S. business fixed investment increased dramatically

Household spending expanded 2.8 percent in 2017, a slight pickup from 2.7 percent in the previous year, and once again made a dominant contribution of 1.89 percentage points to the final economic growth tally of 2.3 percent. The pace of spending rose for goods, up to 3.9 percent, but slowed marginally for services, down to 2.2 percent. Expenditures on durable goods accelerated to a 6.7-percent pace while growth in spending on nondurables slowed down to 2.4 percent. Growth in business fixed investment increased dramatically from 0.7 percent in 2016 to 4.0 percent in 2017. The pace of expansion in residential investment slowed down sharply from 5.5 percent in 2016 to 1.8 percent in 2017. Meanwhile, the reverse was the case for non-residential investment, which rebounded from a contraction of 0.6 percent in 2016 to post a 4.7-percent growth in 2017. Within the latter, investment rebounded both in the area of structures and that of machinery and equipment, while growth in investment in intellectual property products declined. As a result, business fixed investment contributed 0.65 percentage point to GDP growth in 2017, up from 0.12 percentage point in the previous year.

Contribution to GDP growth from net exports was negative again (-0.18 percentage point), but slightly less so than in 2016. Exports shrugged off their 2016 contraction to expand 3.4 percent, but imports accelerated from 1.3 percent in 2016 to 4.0 percent. The contribution to growth from both federal and state and local government spending was near-zero as both federal and state and local expenditures expanded marginally.

As in several previous years, weakness in the first quarter was again the case in 2017, as the economy grew just 1.2 percent. Residual seasonality was partly to blame, as well as a fall in consumer spending on autos and utilities, and lower defence spending. Strong consumer spending and non-residential investment boosted the growth to 3.1 percent in the second quarter of 2017. In the third quarter, investment and net exports pushed the economic growth even higher to 3.2 percent, before slowing down to a more restrained 2.9-percent pace in the last quarter of the year, mainly due to a sharp fall in inventory investment.

Overall, the latest U.S. data show signs of continuing strong recovery with 3.0 percent average annualized growth over the last three quarters of 2017, followed by unexpected first-quarter strength of 2.3 percent in 2018.

| Share in current dollars (%) | Growth from previous year (%) | Contributions to percent change in real GDP (percentage points) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Gross domestic product | 100 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| Household expenditures | 69.6 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 1.86 | 1.89 |

| Goods | 4.7 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 0.81 | 0.85 |

| Durable goods | 10.0 | 5.5 | 6.7 | 0.41 | 0.50 |

| Non-durable goods | 15.1 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 0.40 | 0.35 |

| Services | 44.9 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 1.05 | 1.05 |

| Business fixed investment | 17.1 | 0.7 | 4.0 | 0.12 | 0.65 |

| Residential | 3.5 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 0.20 | 0.07 |

| Non-residential | 13.5 | -0.6 | 4.7 | -0.08 | 0.58 |

| Structures | 2.8 | -4.1 | 5.6 | -0.12 | 0.2 |

| Machinery & equipment | 6.4 | -3.4 | 4.8 | -0.20 | 0.27 |

| Intellectual property products | 4.4 | 6.3 | 3.9 | 0.25 | 0.16 |

| Investment in inventories | 0.1 | -66.8 | -54.5 | -0.40 | -0.11 |

| Net exports of goods and services | -3.6 | 7.5 | 6.1 | -0.23 | -0.18 |

| Exports | 12.8 | -0.3 | 3.4 | -0.04 | 0.40 |

| Goods | 8.8 | 0.3 | 4.5 | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| Services | 4.0 | -1.5 | 1.3 | -0.06 | 0.05 |

| Less imports | 16.5 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 0.19 | 0.58 |

| Goods | 13.5 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 0.11 | 0.51 |

| Services | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Government expenditures and gross investment | 17.0 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| Federal | 6.5 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| State and Local | 10.4 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Tables 1.1.2 and 1.1.6

Combined with other factors such as stronger and earlier federal outlays related to the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, this bodes well for the 2018 growth. Most cyclical indicators suggest that growth will stop accelerating by 2019 due to higher projected resource prices, upward pressure on inflation, a quicker monetary tightening schedule by the Federal Reserve, and global risks. Labor market data indicate that the country is close to full employment as the jobless rate reached 4.1 percent at the end of 2017 and is projected to dip below 4 percent in 2018. The IMF expects GDP growth of 2.9 percent in 2018, slowing down to 2.7 percent in 2019.

The IMF expects U.S. GDP growth of 2.9 percent in 2018, slowing down to 2.7 percent in 2019

Canada’s goods exports to the United States increased by 4.8 percent in 2017, slightly slower than the overall increase of 5.4 percent for Canada’s overall goods exports. Growth in goods imports from the United States rose 2.9 percent, also slower than the overall import growth rate of 4.8 percent.Footnote 2-1 Exports of services to the United States grew 2.7 percent, and imports of services from it grew 2.5 percent. Canada’s top five categories of export commodities to its greatest trading partner were: mineral fuels and oil, automotive products, mechanical machinery, plastics, and wood and articles of wood; its top five imports were automotive products, mechanical machinery, mineral fuels and oil, electric machinery and equipment, and plastics.

China

In 2017, China’s economy did better than many analysts expected. Economic growth accelerated to 6.9 percent (up 0.1 percentage point from 2016 and equal to 2015), surpassing the government’s target of around 6.5 percent. Even more impressively, this occurred while excessive credit growth was being reined in, following years of credit stimulus, previously flagged as a concern by many economic organizations.

China’s economy continued to switch over from investment-fueled to consumption-based growth while decelerating very gradually. Within the industrial sector, growth is slowing down in construction activities, manufacturing and mining. On the other hand, growth was observed to rise in the agriculture and service sectors. Real fixed investment growth continued to slow down, from 6.6 percent in 2016 to 5.7 percent in 2017.

IMF data indicate that China’s real exports of goods and services expanded by 9.2 percent in 2017. Real imports rose at a 6.9-percent pace. General government expenditures as a proportion of GDP were reduced from 31.9 percent in 2016 to 31.5 percent in 2017, and the current account surplus narrowed from 1.8 percent of GDP in 2016 to 1.4 percent of GDP in 2017. Inflation dipped to 1.6 percent, and so did reported unemployment, now at 3.9 percent.

China’s current economic policy targets were identified as pollution control, mitigation of financial system risk and new anti-poverty measures

China’s government, directing its economy to achieve a more sustainable consumption-based growth, is indicating satisfaction with its strong performance in setting its objectives. Current economic policy targets, identified in December’s annual economic work conference, were identified as pollution control, mitigation of financial system risk and new anti-poverty measures. These policies can be expected to slow down economic growth, indicating the Chinese government’s confidence in the strength of the economy to withstand them.

According to the IMF, China’s economy is expected to continue to slow down in the medium term – to 6.6 percent in 2018 and to 6.4 percent in 2019. Labour markets remain stable, and a controlled slowdown in housing is under way. Nevertheless, risks to China’s forecast in the medium term are on the downside. Large commercial indebtedness, excess industrial capacity, and a housing glut are all headwinds against the economy beyond the short term. In the short term, severe risks are associated with the trade spat with the United States, although the trading relationship of these countries is widely believed to be too extensive and lucrative to end in a full-scale trade war (for example, the latest IHSFootnote 2-2 forecast for China cites the risks of a trade war as “non-negligible”, but foresees a deal as the most probable outcome).

Canada’s goods exports to China rose 11.5 percent in 2017, a rate almost triple that of 2016. Meanwhile, Canada’s goods imports from China grew even faster, up 13.3 percent, to reach $42.6 billion. China remains Canada’s second-largest trade partner; Canada’s main export commodities to China in 2017 were oil seeds and miscellaneous plants, wood pulp, wood and articles of wood, automotive products, and ores; Canada’s main import commodities from China were electrical and electronic machinery, mechanical machinery, furniture, toys and sporting equipment, and plastics and articles thereof.

Mexico