Evaluation of the Canadian Police Arrangement and the International Police Peacekeeping and Peace Operations Program

August 2017

Table of Contents

- List of tables and Figures

- Acronyms and Symbols

- Acknowledgements

- Executive summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Background

- 3.0 Evaluation Purpose and Scope

- 4.0 Evaluation Findings

- 4.1 Relevance Issue 1: Continued Need for the Program

- 4.2 Relevance Issue 2: Alignment with Government Priorities; and, Relevance Issue 3: Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

- 4.3 Performance Issue 4: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

- 4.4 Performance Issue 5: Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

- 5.0 Conclusions of the Evaluation

- 6.0 Recommendations

- 7.0 Management Response and Action Plan

- Appendix 1: List of Findings

- Appendix 2: CPA Logic Model

- Appendix 3: Evaluation Objectives and Questions

- Appendix 4: Missions of Focus

- Afghanistan

- Haiti

- West bank

List of Tables and Figures

- Table 1: IPP Program Funding 2011/12 to 2015/16. 3

- Table 2: Average Deployment Number Broken Down by Affiliation per FY.. 4

- Table 3: IPP 2015 Evaluation Interview Breakdown by Department 7

- Table 4: Number of Missions and Deployments per FY.. 12

- Table 5: IPP Program positions at RCMP HQ

1 . 44 - Table 6: Average Number of RCMP HQ Support Staff (FTEs) & Total Salary Dollars per FY.. 45

- Table 7: Activity and Staffing with Total Percentage of IPP Program Funds Spent per FY.. 46

- Table 8: RCMP A-Base Funds and Incremental Costs per FY.. 47

- Table 9: Forecasts and Actual Costs of Missions of Focus per FY.. 49

- Table 10: Forecasts and Actual Costs of RCMP HQ Support Staff 50

- Table 11: Forecasts and Actual Costs of Rapid Deployment Capacity 51

- Table 12: ODA and Non-ODA portions of the IPP Program.. 52

- Figure 1: Evaluation Interview Breakdown by Categories. 7

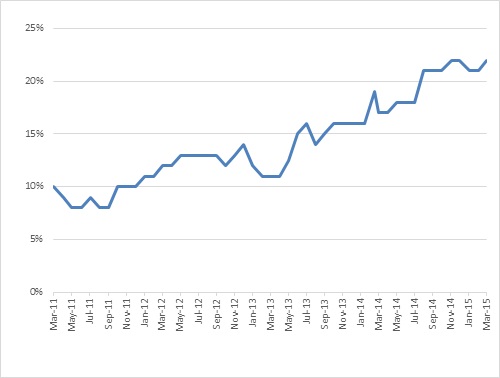

- Figure 2: Percentage of Female Officers Deployed through the IPP Program (March 2011-March 2015) 33

Acronyms and Symbols

- ACCBP

- Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program (GAC)

- ADM

- Assistant Deputy Minister

- AFP

- Australian Federal Police

- ANA

- Afghan National Army

- ANP

- Afghan National Police

- ANSF

- Afghan National Security Forces

- CF

- Canadian Forces

- CFO

- Chief Financial Officer

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- CONOPS

- Concept of Operations

- CPA

- Canadian Police Arrangement

- CSC

- Correctional Services Canada

- CSTC-A

- Combined Security Transition Command - Afghanistan

- CTCBP

- Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program (GAC)

- DG

- Director General

- DND

- Department of Defence

- DPR

- Departmental Performance Report

- DRC

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- DVI

- Disaster Victim Identification

- EAC

- Evaluation Advisory Committee

- EBP

- Employee Benefits Plan

- ESP

- Enhanced Selection Process

- EU

- European Union

- EUPOL Afghanistan

- European Union Police Mission in Afghanistan

- EUPOL COPPS

- European Union Police Mission in the Palestinian Territories

- FIPCA-PNH

- Initial Training and Professional Development for the Haitian National Police's Managerial Staff

- FTE

- Full-Time Equivalent

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GC

- Government of Canada

- GPSF

- Global Peace and Security Fund

- HNP

- Haitian National Police

- IAE

- International Assistance Envelope

- IDG

- International Deployment Group

- IDS

- International Deployment Services (RCMP)

- IHPW

- International Health Protection and Wellness (RCMP)

- ILDC

- International Liaison and Deployment Centre (RCMP)

- IMR

- Individual Monthly Report

- IPOB

- International Peace Operations Branch (RCMP)

- IPCB

- International Police Coordination Board

- IPD

- International Policing Development (IPD)

- IQR

- Individual Quarterly Report

- IRC

- Deployment and Coordination (GAC)

- ISF

- International Strategic Framework (RCMP) (PS)

- KABUL

- Embassy of Canada in Afghanistan

- MC

- Memorandum to Cabinet

- MINUSTAH

- United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti

- MOU

- Memorandum of Understanding

- MRAP

- Management Action Response Plan

- NAM

- Needs Assessment Mission

- NATO

- North Atlantic Treaty Association

- NGO

- Non-Government Organization

- NTM-A

- NATO Training Mission- Afghanistan

- ODA

- Official Development Assistance

- ODAAA

- Official Development Assistance Accountability Act

- OECD-DAC

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development-Development Assistance Committee

- Op PROTEUS

- Canadian Forces Contribution to the United States Security Coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian Authority

- OSCE

- Organization for Security Cooperation in Europe

- PA

- Palestinian Authority

- PCO

- Privy Council Office

- PCP

- Palestinian Civil Police Force

- PMF

- Performance Management Framework

- PS

- Public Safety Canada

- PRMNY

- Canada’s Permanent Representative Mission to the United Nations in New York

- PRNCE

- Embassy of Canada in Haiti

- RCMP

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- RDT

- Rapid Deployment Team Roster

- ROL

- Rule of Law

- RPP

- Report on Plans and Priorities

- RMLAH

- Representative of Canada to the Palestinian Authority

- SAAT

- Selection Assistance and Assessment Team

- SGBV

- Sexual and Gender-Based Violence

- SO

- Strategic Outcome

- SOP

- Standard Operating Procedure

- SPA

- Senior Police Advisor

- SPC

- Standing Police Capacity (UN)

- SSR

- Security Sector Reform

- START

- Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force (GAC)

- STL

- Special Tribunal for Lebanon (UN)

- TBS

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- TLD

- Third Location Decompression Program

- ToRs

- Terms of Reference

- UN

- United Nations

- UN DPKO

- United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations

- UNPOL

- United Nations Police

- UNSC

- United Nations Security Council

- USSC

- United States Security Coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian Authority

- WG

- Working Group

- WoG

- Whole-of-Government

- WPS

- Women, Peace and Security

Acknowledgements

The evaluation team would like to extend its appreciation to the many individuals and organizations who agreed to participate in the interviews, both in-person and by telephone. A number of people in Canada and abroad graciously gave their time and identified additional sources. The participants included: RCMP police officers, RCMP personnel, public servants, deployed police officers from provincial/municipal police forces, representatives from the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (UN DPKO), Heads of Mission both for Canadian embassies and European Union (EU) peacekeeping missions and other non-governmental stakeholders. Also, we would like to thank representatives from likeminded countries who shared their perspectives regarding police deployments to peacekeeping operations.

Executive Summary

Background

The International Police Peacekeeping and Peace Operations (IPP) Program has deployed more than 3,800 police officers in more than 30 countries. IPP deployments are comprised of Canadian police officers from the RCMP as well as from provincial/municipal police partners. The IPP Program is guided by a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) entitled the Canadian Police Arrangement (CPA) that outlines the managerial and accountability relationship between the three Partners involved in the IPP Program: Global Affairs Canada (GAC); Public Safety Canada (PS); and, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The goal of the IPP Program is to support Canada’s commitment to build a more secure world through police participation in international peace operations.

In accordance to the Treasury Board of Canada’s Policy on Evaluation (2009), the respective evaluation sections of these Partner departments conduct the evaluation for the IPP Program. The evaluation covers a period of four fiscal years from April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2015.

Key Findings

Finding 2: The IPP Program considered the needs and priorities of missions. Notwithstanding the political and security sensitivities, there are examples where the Program was limited in its ability to meet the needs of mission.

Finding 3: Anecdotally, the Program referenced domestic benefits to Canada as a result of its participation to CPA missions. The most frequently identified domestic benefit to Canada was the skills that Canadian police officers either acquired and/or enhanced.

Finding 5: The IPP Program complemented the Government of Canada’s and the international community’s approach to fragile and conflict affected states. However, there is still room to improve coherence by enhancing synergies and increasing coordination in similar thematic areas.

Finding 7: The IPP Program has developed performance measurement tools to track, monitor and report on deployment activities and outputs. However, the tools were not consistently used to report on performance nor were they directly aligned with the outcomes in the CPA logic model.

Finding 8: While the IPP Program has contributed to the achievement of results under its immediate and intermediate outcomes, the extent to which they were met could not be measured as there was a lack of performance information. In particular, this was evident in the outcomes of strengthened judicial systems and domestic benefits.

Finding 11: Deployed Canadian police officers contributed to gender initiatives to promote the participation and protection of women in the affected areas. However, there was limited evidence to suggest that gender is strategically taken into consideration in mission selection criteria, planning and implementation.

Finding 15: The IPP Program has numerous reporting requirements. The reports generated are not consistently produced nor do they indicate planned results and overall impact.

Finding 16: The number of IPP Program support positions classified and staffed at RCMP headquarters has fluctuated below the authorized 54 FTEs. Based on the ratio of 3:1 between operational personnel in mission to headquarters support staff, the Program was understaffed in relation to the number of deployments in 2011/12 and 2012/13, and overstaffed in 2013/14 and 2014/15.

Finding 20: Lessons learned were captured inconsistently in IPP Program documents and there was limited evidence that these were routinely incorporated into on-going and future missions.

Recommendation #1 The IPP Program should strengthen and streamline its performance measurement and reporting tools to consistently capture outcomes and lessons learned at both the mission and program level. In particular, the CPA performance information should be revised to reflect and further define expected results under the thematic areas of gender, judicial reform and domestic benefits.

Recommendation #2 CPA Partners should update and implement operational and guidance documents in order to:

- increase flexibility of deployments and develop guidance that strengthens the IPP Program’s ability to address the needs of the police force in the fragile or conflict affected states;

- consistently reflect all considerations and apply the tools that support the mission selection process;

- satisfy and streamline the reporting requirements at all levels;

- increase communication regarding IPP deployments with GC representatives in Canada and at missions;

- clarify and refine ministerial roles and responsibilities that reflect an amalgamated GAC; and,

- provide clear expectations for supporting exercises such as tracking of requests and lessons learned.

Recommendation #3 The RCMP is encouraged to continue to document the roles and staffing levels of the 54 FTEs in order to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the resourcing model.

1.0 Introduction

The evaluation for the International Police Peacekeeping and Peace Operations (IPP) Program was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board of Canada’s Policy on Evaluation (2009). The IPP Program is guided by a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) entitled the Canadian Police Arrangement (CPA). This MOU was renewed for a period of five years as of April 1, 2011. The MOU defines the managerial and accountability relationship between the three Partners involved in the IPP Program: Global Affairs Canada (GAC)Footnote 1; Public Safety Canada (PS); and, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

The respective evaluation sections of these Partner departments are mandated to conduct evaluations of direct program spending once every five years. The last evaluation of the IPP Program was finalized in 2012.

The target audiences for this evaluation are:

- the Government of Canada (GC), including Parliament and other government departments that are relevant to the program;

- GAC, PS and RCMP senior and program management; and,

- the Canadian public, including relevant stakeholders.

The evaluation of the IPP Program covers a period of four fiscal years from April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2015.

2.0 Background

Since 1989, Canada has participated in more than 60 international police peacekeeping operations led by: the United Nations (UN), the European Union (EU), the Organization for Security Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), bilateral agreements, and those conducted by other international partners, commissions or institutes. The IPP Program has deployed more than 3,800 police officers in more than 30 countries.

As part of the international community’s efforts to promote comprehensive and sustainable rule of law (ROL), Canadian police officers have played a wide range of roles within each mission, from training and mentoring their police counterparts and providing humanitarian assistance to ensuring security for elections and investigating human rights violations. International police peacekeepers support longer term Security Sector Reform (SSR) and conflict prevention efforts. Canadian police officers also contribute to efforts to restore human security, social stability and ROL as preconditions for longer-term development.

2.1 Mandate and Scope of the IPP Program

The CPA MOU outlines the managerial responsibilities and the accountability relationships between the three Partner departments: GAC, PS and RCMP. The Program’s Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) outlines how the three departments carry out their responsibilities as defined in the MOU.

The Program funding was initially approved in 2006 and renewed in 2011. It provides the Program with stable and consistent funding. It also allows provincial/municipal police partners (other than the RCMP) to backfill positions in Canada, while their officers are deployed abroad.

The goal of the IPP Program is to support Canada’s commitment to build a more secure world through police participation in international peace operations. The objectives of the CPA are as follows:

1) Provide police expertise, training and advice to police services, in the context of integrated peace operations, in states that require assistance, including those which have recently experienced or are threatened by conflict, so that local police forces may carry out their policing responsibilities in accordance with democratic principles and international human rights conventions;

2) Strengthen the GC’s ability to plan and develop timely and coordinated whole-of-government (WoG) responses to international crises in support of Canadian foreign assistance priorities; and

3) Promote comprehensive and sustainable ROL through the re-establishment of effective public institutions such as law enforcement and judicial systems.

While not its primary function, the IPP Program also seeks to maximize the Canadian domestic benefits of international police peacekeeping activities wherever possible, including through contributions to improved domestic policing capacity and improved security in Canada.

The scope of the Canadian police expertise provided under IPP operations includes:

- International police peacekeeping and peace operations: training, advising and mentoring of national police in the context of multidimensional integrated operations, as part of broader police reform efforts in countries threatened by conflict or instability;

- International criminal courts and tribunals as well as international commissions and inquiries; and,

- Technical assistance which can include response to crisis, development of international policy and non-peacekeeping-related police deployments to respond to international peace and security challenges.

The expected results of the Program are defined in its Logic Model in Appendix 2.

2.2 Resources of the IPP Program

The Program is funded through the Peace and Security Pool of the International Assistance Envelope (IAE) which is separated into two funding types. Table 1 and discussion in this section is based on policy and financial authorities approved for the IPP Program in 2011. Subsequent changes to IPP Program funds are presented in Finding 17 (Section 4.4), addressing Performance Issue 5: Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy.

The RCMP receives the first type, $36.8M annually in direct A-base funds that supports salaries and benefits for the deployment of up to 170 Canadian police officers abroad and a cadre of 54 staff at RCMP headquarters to administer the program. RCMP HQ staff support the recruitment, selection, training, medical and psychological assessment, deployment, support and reintegration of Canadian police officers for overseas missions. The $36.8M (later reduced to $35.5)Footnote 2 portion also includes $500,000 for rapid deployment capacity. In addition to the 54 staff at RCMP, 1.5 full-time equivalents (FTE) at GAC and 1.5 FTE at PS support the implementation of the Program over the reference period of the evaluation, for each fiscal year. Positions in PS and GAC are not funded by the IPP Program.

GAC receives the second type, $11.4M annually to support the incremental costs of deployments. Incremental costs are to be used for, but not limited to: allowances, travel, uniforms and equipment, vehicles and telecommunications and specific health costs. These funds are provided by GAC to the RCMP via the Global Peace and Security Fund (GPSF) on a cost-recovery basis.

| 2011/12 | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 1 | Total | Source of funds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $M | $M | $M | $M | $M | $M | $M | |

Salary and Overhead | 36.3 | 36.3 2 | 36.32 | 36.32 | 36.32 | 181.52 | A-base is on-going and to be reprofiled |

| Rapid Deployment Capacity | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.5 | A-base and ongoing |

| Incremental Costs | 11.4 | 11.4 | 11.43 | 03 | 11.43 | 45.6 | GAC – GPSF |

| Sub Total | 48.2 | 48.2 | 48.2 | 48.2 | 48.2 | 241 | |

| Haiti Reconstruction | 12.74 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 12.7 | IAE Crisis Pool (1 yr) |

| Total | 60.95 | 48.2 | 48.2 | 36.8 | 48.2 | 242.3 | |

| 1 2015/16 is outside the evaluation reference period 2 Salary and overhead amount does not reflect the removal of the legal contingency fund, see Finding 17 3 Incremental costs in these fiscal years was subject to GPSF renewal in 2013. 4The deployment of up to 50 police officers was authorized until 2012 to support Haiti post-earthquake stabilization efforts. Of this amount, $2.6M is sourced from the reprofile of unused IPP funds in 2010/11. Separate funding of $10.1M was sourced from the IAE Crisis Pool in 2011/12. 5Any unused IPP funds in 2010/11 above the $2.6M that will be reprofiled for Haiti, will be used to reduce the required transfer from the IAE to the IPP in 2011/12. | |||||||

Affiliation of deployed officers

IPP deployments are comprised of Canadian police officers from the RCMP as well as from provincial/municipal police partners. As such, the RCMP regularly liaises and coordinates operations with domestic police partners who deploy officers. Provincial and municipal police partners began contributing members in support of international police deployments in 1995. At the time of analysis, the RCMP had a total of twenty-five active MOUs in place with participating provincial and municipal police partners.

The participation of the provincial and municipal police partners, retired RCMP police officers and active RCMP officers are provided in Table 2. Over the reference period, the ratio of provincial/municipal police resources to RCMP resources for the Program varied from 60:30Footnote 3 percent to 70:30 percent.

| 2011/12 | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deployment # | % 1 | Deployment # | % | Deployment # | % | Deployment # | % | |

| Provincial / municipal partners | 126 | 60% | 110 | 67% | 83 | 66% | 67 | 70% |

| Retired RCMP | 21 | 10% | 11 | 7% | 0.5 | 0.4% | 0 | 0 |

| RCMP | 62 | 30% | 44 | 27% | 43 | 34% | 29 | 30% |

| Total | 209 | 100% | 165 | 100% | 126.5 | 100% | 96 | 100% |

| 1 Note 1- Average deployment percentages have been rounded to the nearest whole number. | ||||||||

2.3 Governance of the IPP Program

The CPA MOU and the CPA SOP outlines the managerial and accountability relationship and the authorities to approve deployments in five different categories. Three of the deployment categories are: deployments to peacekeeping and peace operations, international criminal courts and tribunals; and, technical assistance which require the approval of the Ministers that are responsible for the IPP ProgramFootnote 4. Ministerial approval will also be sought if there is a significant change in the mandate of an IPP mission or if Canada's commitment increases above the levels previously authorized. Two other deployment categories are: rapid or short term deployments that respond to police training and rapid deployments that respond to specific crisis situations which requires the approval of the Working Group (WG) or the Director General (DG) Advisory Committee. The Working Group and Committees are described in further detail below.

As per the MOU and the SOP, GAC provides foreign policy expertise and leadership such as identifying activities where police can contribute to local peacekeeping, stabilization and peacebuilding efforts that are consistent with Canadian foreign policy and international security objectives. As part of the development component, GAC also provides in-depth country and cultural knowledge and enhances linkages between police interventions and longer term development work. The MOU outlines the structure and management of the three CPA committees that are all chaired by GAC:

- Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) Steering Committee –Its role includes discussing and approving ongoing Canadian policy priorities for peace operations; reviewing the framework and activities under the terms of the CPA MOU; and, making recommendations to the Participants’ Ministers regarding proposed amendments to the MOU. Beyond the signatory departments of the CPA, the Department of National Defence (DND), the Department of Justice, Correctional Service of Canada (CSC), the Privy Council Office (PCO), Department of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) may also participate as observers.

- Director General (DG) Advisory Committee – Established after the 2012 CPA Evaluation, this Advisory Committee is responsible for: providing advice to the CPA Working Group, monitoring and assessment IPP Program activities and finances; reviewing and approving annual reports; and, reviewing and approving rapid deployment activities and assessment missions. The committee is comprised of DG-level representatives of the CPA signatory departments, and additional observers as appropriate.

- The CPA Working Group (WG) – Its responsibilities include, but are not limited to: coordination of day-to-day activities within the CPA; strategic analysis and input that supports the CPA Steering and Advisory Committees; monitoring activities and finances related to progress of missions; and, preparation of memoranda to Ministers as well as amendments to the CPA MOU. Representation on the WG includes the Directors with the responsibility for the CPA or their delegates.

The RCMP manages all stages of the deployment of Canadian police officers, including selection, preparation, training, medical and psychological assessment, deployment, support and reintegration of personnel providing Canadian police peacekeeping expertise internationally.The RCMP also provides input on Canadian domestic policing issues and supports the identification, selection and planning of new missions.

PS ensures that the IPP operations are consistent with Canadian policing policy and overall requirements and ensures Canadian domestic security priorities are advanced and represented.

3.0 Evaluation Purpose and Scope

The evaluation assessed the IPP Program’s relevance and performance by applying a mixed-method approach using multiple lines of inquiry where both qualitative and quantitative methods were applied. Data collected was aggregated to leverage existing information, smaller sample sizes and missions of focus to address evaluation objectives which are elaborated upon below.

3.1 Evaluation Objectives

In accordance with the 2009 TBS Policy on Evaluation, a systematic evidence-based data collection process was applied to assess the relevance and performance of the IPP Program. The objectives of the evaluation were:

- To determine the on-going need of the IPP Program to strategically support the GC’s international peace and security outcomes;

- To determine the extent to which the IPP Program has been effective and efficient in achieving its outcomes;

- To determine whether the IPP Program’s governance and planning structure supports an efficient and economic allocation of resources; and,

- To determine the extent to which progress has been made on the implementation of recommendations from the 2012 evaluation.

3.2 Evaluation Design

The evaluation objectives were elaborated on with detailed evaluation questions (Appendix 3) which addressed specific aspects of relevance and performance. Some evaluation questions were further developed into sub questions with respective indicators that were reflective of different departmental structures.

Information gathered from interviews, documents, and RCMP and GAC financial units was analyzed to respond to evaluation questions. Evidence was triangulated to determine trends, similarities, and points of divergence or convergence. Data collection included an updated Management Response and Action Plan (MRAP) to the 2012 evaluation.

In 2015, the evaluation team refocussed its efforts to develop preliminary findings that addressed key evaluation questions in order to provide timely information for the renewal of the Program. The key evaluation questions were 1.1, 1.3, 2.3 and parts of question 5.2 (Appendix 3).

Subsequently, all findings and the draft evaluation report were reviewed during the Evaluation Advisory Committee (EAC) meetings where EAC members were solicited for their feedback and fact validation.

3.3 Data Sources

Interviews

A purposeful selection of interviewees was employed, based on the individual’s background knowledge and current or previous roles and responsibilities. A number of them were selected as they were able to provide extensive and detailed information that would otherwise not have been available and were therefore a valuable source of information. Consultation with IPP Program staff helped to identify and prioritise the interviewees for in-person or telephone interviews. PS and GAC conducted semi-structured interviews while RCMP conducted structured interviews.

In using a purposeful sampling method, views from a few interviewees may be presented for the following reasons: they captured views of the Partner departments; they were key informants whose position and knowledge were of particular relevance; they represented views of their organisation; or, the purpose of the question was to obtain broader views. Finally, it is important to note that in quantifying interviewees, the number of interviewees that may be qualified to answer a particular question may be from a small population of five or ten, rather than the total sample of 97 interviewees of this evaluation.

Some interviewees fell into more than one category but were captured in the following table based on the primary role for which they were interviewed. Of interest, two interviewees in the stakeholder category were also police coordinators from provincial/municipal police partners. Four interviewees under the category of Program and Policy were also deployed police officers, while one deployed police officer was also affiliated with Program and Policy.[1] Other stakeholders included heads of EU peacekeeping mission, relevant policy staff within the EU’s European External Action Services, and relevant policy staff within the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (UN DPKO).

| CPA Partners | Program/Policy | Deployed Police | Senior Management | Stakeholders | Total by Partner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAC | 36 | 0 | 10 | 13 | 59 |

| RCMP | 17 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 33 |

| PS | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Total by type | 55 | 12 | 15 | 15 | 97 |

Figure 1: Evaluation Interview Breakdown by Categories

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

A pie chart showing Evaluation Interview Breakdown by Categories

- 12% are deployed police

- 16% are senior management

- 5% are stakeholders

- 57% are from program and policy

Document, performance and financial data review

Foundational documents of the IPP Program were used to assess the alignment with departmental priorities and strategic outcomes. Operational reports tracked Program planning, finances, activities and performance. External sources, including UN reports, media articles, NGO surveys and third party publications, provided useful background literature for understanding Program relevance, impact on beneficiaries and possible performance results.

Missions of Focus

Missions in Afghanistan, Haiti, and the West Bank were selected as areas of focus for the evaluation. Detailed descriptions of the missions are found in Appendix 4. Factors that were considered in selecting these deployments included: diversity in the types of deployment missions within the reference period; strategic linkages to the GC priorities; consultations with program representatives in the three partner departments; and, the expected presence of reliable and available data sources. The rationale for selecting these three missions is expanded upon below:

Afghanistan

From 2003 to 2014, Canadian police officers deployed to Afghanistan supported the UN-mandated, NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and the broader international effort to make Afghanistan a more stable and self-sufficient state. The Program deployed police officers to the NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan/Combined Security Transition Command-Afghanistan (NTM-A/CSTC-A), the European Union Police Mission in Afghanistan (EUPOL Afghanistan) and the International Police Coordination Board (IPCB). From 2011 to 2014, Canada’s engagement in police reform focussed on four niche areas: leadership and management training and mentoring; specialized policing (advanced investigational and anti-corruption policing); Ministry of Interior reform and capacity building; and, community policing. The presence of several IPP missions in Afghanistan over the reference period and presence of other GC security and development programming provided a unique opportunity to compare and contrast Canada’s whole-of-government (WoG) engagement within one country.

Haiti

The UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) is Canada’s largest and longest-standing police contribution which has accounted for almost half of all IPP deployments since the beginning of the Program. Canada has contributed to areas such as community policing, middle management mentoring and serious and organized crime. IPP Program deployments to Haiti provided a potential opportunity to observe the intermediate and immediate outcomes of the logic model due to the Program’ s longer period in this fragile state.

West Bank

Canada deployed police officers to two missions in the West Bank over the reference period to assist in the reform of the Palestinian Civil Police (PCP): the European Union Police Co-ordinating Office for Palestinian Police Support (EUPOL COPPS) and the U.S Security Coordinator (USSC) team under Operation PROTEUS. The EUPOL COPPS mission seeks to support PCP reform and development, strengthen and support the criminal justice system, and improve prosecution - police interaction. Separately, a senior police officer member works as a technical police advisor to the U.S Security Coordinator (USSC) team under Operation PROTEUS. The USSC has a mandate to encourage co-ordination on security matters between Israel and the Palestinian Authority (PA). These two missions were selected to capture issues that may arise in small scale non-UN deployments.

3.4 Limitations

The following section outlines the limitations of the evaluation:

- There were no on-site interviews of the missions of focus due to the timing of elections in Haiti, the closure of missions in Afghanistan, and the small size of the Canadian police contingent in the West Bank. The evaluation team acknowledges that the lack of field visits may have limited the extent to which efficiencies and effectiveness on the ground were captured. For instance, there were limitations to accessing persons who had first-hand observations on sustained results, indirect benefits and the extent of positive or negative intended and unintended impacts. This would include candid feedback from beneficiaries and stakeholders. Beneficiaries include the local/national police force to which the Canadian police officers were deployed, vulnerable sections of the population or targeted communities and neighbourhoods. Stakeholders include other countries and international organisations that worked on SSR in the fragile area and other police and peacekeeping officers deployed to support the local police force.

- Where possible, the evaluation team mitigated this limitation by consulting various secondary sources including the UN, the IPP Program reports, academic and NGO literature to name a few. The number of interviews was also increased with previously deployed police officers, program and policy staff and stakeholders with prior experience in the field.

- The rotational nature of deployments hampered the continuity of observations for the evaluation. Evaluation methods mitigated some of these issues by tracking individuals who had current and historical knowledge on the specific files over the reference period of the evaluation.

- Incomplete development of a Performance Measurement Strategy (PMS) limited the ability of the evaluation to assess whether the IPP Program achieved its expected outcomes as defined in the CPA Logic Model (Appendix 2). Where there was incomplete or inconsistent information documented in results reporting, the evaluation team consulted additional sources for results and noted areas where gaps remained. Analysis was supported by interviews that addressed progress towards achievement of outcomes and documents that reported on broader achievements related to the intermediate and ultimate outcomes of the Program.

In addition, there are numerous factors independent from police reform and the Program’s contributions that affect a country’s stability and fragility, including the affected area’s own governance structures, socio-economic development and the role of other foreign actors. As much as possible, the evaluation took these external factors into account.

4.0 Evaluation Findings

4.1 Relevance Issue 1: Continued Need for the Program

Finding 1: The IPP Program addressed a continued need for international police peacekeeping and peace operations missions, despite a steady decline in authorized missions and deployment numbers. While needs varied depending on the particular mission, the Program demonstrated strengths including access to diverse and professional police officers from across Canada.

As demonstrated through multilateral peacekeeping operations, special political missions and other stabilization operations, the nature of police in peacekeeping and peace operations is changing. Their roles within the host state may include SSR, operational support for local police and other law enforcement institutions, or conducting interim policing and other law enforcement duties.

Traditional police deployments of the United Nations have been limited to monitoring, observing and reporting.Footnote 1 These traditional types of deployments have been declining, according to the documents reviewed, and the Program has been exploring more strategic, non-traditional deployment opportunities. As demands on police deployed are increasingly diverse and complex,Footnote 6 police deployments now have roles in areas such as technical assistance, co-location training, and mentoring programs to support host state policing and other law enforcement institutions. IPP deployments have taken on some of these roles which are described in more detail throughout the report. The UN Security Council (UNSC) recognizes that UN policing-related work is an invaluable contribution to peacekeeping, post-conflict peacebuilding, security and ROL and creates a basis for development.

Responsiveness to multidimensional issues of fragility

The evaluation found that the IPP Program has the ability to deploy to different contexts and respond to varying institutional and mission needs. The IPP deployments assisted, and continue to assist, in police reform through training and capacity building missions.

Afghanistan

- Afghanistan remains a fragile state after more than 30 years of conflict and insurgency that continues to pose a threat to its peace and security. The Government of Afghanistan has made progress in its transition towards democracy in recent years but grave concerns persist in terms of the government’s commitment to fight corruption and protect human rights. The government also continues to face obstacles in its ability to provide security to the Afghan people with the existence of a resilient insurgency that has weakened state control over the territory, an underground economy of illicit drug production, and the withdrawal of international security forces.

- The Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF), comprised of the Afghan National Army (ANA) and the Afghan National Police (ANP), gradually assumed responsibility for Afghan security beginning in June 2013 but the ANSF’s effectiveness was limited by weak institutional and human capacity. The insurgency continues attacks in Kabul and the northwestern ethnic Tajik and Uzbek regions, which resulted in the deaths of more than 4,600 members of the ANSF in 2014 alone. Canadian police officers were able to address police reform in Afghanistan prior to their withdrawal in 2014. Examples of their contribution include assisting in training and doctrine development in the NATO-led mission and establishing a border management system in the EU-led mission (detailed descriptions in Appendix 4).

Haiti

- Haiti is the poorest country in the Americas and has struggled with political instability and rampant corruption in its transition to a stable democracy. Government infrastructure remains weak and resources are limited which directly impacts the ability of the state to provide security to its population, including through delivering on police reform commitments.

- IPP deployments to Haiti addressed a need for international police peacekeeping and the Program demonstrated an ability to adapt to challenges on the ground. To contribute more directly to the needs of the Haitian National Police (HNP), the IPP Program created specialised teams (details in Finding 2). While great strides have been made on police reform in Haiti with the assistance of MINUSTAH and Canadian police officers, the HNP still scores high in terms of corruption in the public sector, demonstrating a continued need for international support.Footnote 7

West Bank

- The protracted Israeli-Palestinian conflict has contributed to weak institutions, underdeveloped infrastructure and widespread criminality and unrest in the region. The economic situation in the West Bank, characterized by high unemployment and widespread poverty, is a major contributing factor to social unrest. Violent clashes between Palestinians and Israeli Security Forces are common place. Tensions between the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Hamas have also contributed to an unstable security environment. The Palestinian Civil Police Force’s (PCP) limited control over the territory and borders, with nearly 60 percent of the region administered by Israel, creates additional challenges for police reform in the region.

- Prior to the establishment of the PCP in 1994, the West Bank did not have a functioning police force and the area was largely controlled by clans and warlords. Since 2005, the EU has been providing training to the PCP to professionalize the force and build capacity. The IPP Program began deploying Canadian police officers to EUPOL COPPS in 2008 and contributed to the broader goals achieved under the mission. Prior to the arrival of international forces, public confidence in the PCP was low and police corruption was rampant. The PCP had limited ability to patrol during periods of intense fighting as they were perceived by Israeli Security Forces as combatants rather than a legitimate security force. While progress has been made in the West Bank, the PCP still require training and capacity building to enhance accountability, establish reporting mechanisms, and ensure greater oversight.

Access to diverse and professional police officers

The evaluation found that Canada, as one of only a few countries which deploys serving police officers, is a leader in both civilian policing and Security Sector Reform (SSR). The IPP Program can draw professional police officers from multiple police partners across Canada which allows it to draw upon a wide range of skill sets.

Interviews provided evidence that Canadian police officers were valued for their knowledge, language abilities, cultural sensitivity, emphasis on human rights and expertise in thematic areas such as community policing and sexual and gender based violence (SGBV). Others expressed that Canadian police officers work well with the local police, are well-respected, professional, and proactive. Sources noted that Canada is a global leader in deploying highly trained and effective police officers.

Decrease in IPP deployment numbers and authorized missions

The authority to deploy Canadian police officers requires securing approval from the Ministers of the three Partner departmentsFootnote 8. Only short term rapid deployments for crisis situations are approved at the WG or DG-level Committee.Footnote 9The evaluation found that the reported number of officers deployed, both authorized and actual per mission varied by data source. For instance, the 2012/13 Annual Report stated that deployments ranged between 125 and 185. A Deployment Table generated by International Liaison and Deployment Centre (ILDC) in the RCMP revealed that deployments ranged between 142 and 174 for the same period. Based on Program documentation and/or performance data, it was not clear why this variance existed. However, the Program staff informed evaluators that deployment numbers can vary depending on when the information was extracted due the officers rotating in and out of a mission.

Drawing from various Program data sources, there were a total of 17 IPP Program missions over the reference period. These missions do not include representation at Canada’s Permanent Representative Mission to the UN in New York (PRMNY), the deployment to the UN Standing Police Capacity Unit in Brindisi, Italy and the position at the UN DPKO. The number of missions steadily declined from 2011/12 to 2014/15 (see Table 4). This decline can be attributed to several factors, namely, the fulfillment of mission mandates and/or the cancellation of some missions.

| # of Missions | # of Authorized Deployments | # of Actual Deployments (Avg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011/12 | 17 | 265 | 210 |

| 2012/13 | 11 | 204 | 165 |

| 2013/14 | 7 | 148 | 126 |

| 2014/15 | 3 | 111 | X1 |

| 1 Data source CPA annual reports. There was no Annual Report completed for 2014/15 at the time of the evaluation. | |||

In 2012/13, a comprehensive review of the Program’s mission resulted in GC decisions to realign IPP deployments. The Review included the foreign policy priorities of the time, Canadian police participating in the mission, their accomplishments, and their role as part of WoG efforts. Subsequently, missions to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ivory Coast and South Sudan were closed. Personnel already deployed to these three missions were permitted to carry out the remainder of their deployments into 2013/14. Further, missions to Afghanistan concluded in 2013/14. In January 2015, the Program received Ministerial authorization for up to ten police officers to be deployed to Egypt and in March up to five police officers to be deployed to Libya. However, these deployments never occurred due to challenges reaching agreement with the host state or organization on deployment details, or security considerations.

Program responsiveness using rapid deployments

The IPP Program has the ability to respond to unpredictable policing needs and short term requests, including in crisis situations or post-conflict contexts. The Program, specifically the ILDC within the RCMP, developed a Rapid Deployment Team Roster (RDT) to respond to an increase in the number of requests for international Canadian assistance that often has very short timelines. The RDT also responds to an interest to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of Canada’s policing engagements. Assessment and approval to deploy from the RDT can be done by the DG committee within 24 hours if required.

The police officers on the RDT are able to deploy at short notice for up to 6 months at a time. The International Deployment Services (IDS) prepares job bulletins to recruit potential candidates from across the RCMP and provincial/municipal police partners. Successful members are placed on the roster for one year. As of March 2016, approximately 33 candidates had been assessed and considered for the RDT. However, at the time of analysis, no police officers were deployed from the RDT.

One situation where a rapid deployment capacity may be necessary is with Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). For example, following the 2011 tsunami in Japan, the CPA was asked to cover the costs of deploying municipal and provincial officers. At the time, there were no clear guidelines or GC lead to respond to these types of requests. Consequently, the CPA partnered with OGDs responsible for disaster response and developed guidelines for DVI in 2012/13. The document provides guidance for GC officials in responding to situations where a DVI request is received from an international body. Specifically, the document provides direction on how to respond to a request, how such a deployment would be governed, and potential sources of funding. The DVI guidelines were approved by the DG Advisory Committee and are included in the CPA SOPs as an annex. Subsequent rapid deployments from the Program to the Philippines in 2013 (Typhoon Haiyan) and to the Ukraine in 2014 (MH17 plane crash) were both part of larger international teams.

Finding 2: The IPP Program considered the needs and priorities of missions. Notwithstanding the political and security sensitivities, there are examples where the Program was limited in its ability to meet the needs of mission.

A majority of interviewees agreed that the Program met the needs of missions. However, some of these respondents mentioned that the degree to which mission needs were met varied. Some also noted the difficulty of measuring progress towards the achievement of mission needs. In particular, the Program’s limits on deploying civilian subject matter experts, organising bilateral deployments and flexibility in deployment duration and timing limited its ability to fully meet the needs of missions. It is important to note that the varying political and security sensitivities of the affected region may have also impacted the ability of the Program to respond to mission needs.

Afghanistan

- In general, the Canadian police officers deployed to Afghanistan met the needs of the NTM-A/CSTC-A, EUPOL Afghanistan and the IPCB. Interviews confirmed that Canadian police officers were highly valued for their skills, expertise and overall quality and professionalism. In particular, Canadian officers adopted a leadership role in promoting gender awareness and training. The Program also demonstrated adaptability in Afghanistan once the mission moved from Kandahar to Kabul where the training needs of the ANP were different. In Kandahar, the local police required basic training whereas the Afghan police in Kabul required more specialized training. A few interviewees noted that there was also frustration expressed with Canadian police deployments to NTM-A/CSTC-A as these positions did not always draw upon the expertise and skills of the officers.

- Despite the challenging security and political environments, the majority of Kandaharis polled in 2011 by the Asia Foundation reported perceptions of improved security in their community. The gains, though fragile can be attributed in part to the increase in capability of the ANSF through efforts of Canadian police officers. EUPOL conveyed that they would have liked Canadian police officers deployed under the IPP Program to remain with the EU mission until the end of its mandate in 2016 and continued to express a need for Canadian police officers once Canada withdrew.

- The Program addressed ANP reform which is only one element of law enforcement under the purview of the Ministry of the Interior (MoI) in Afghanistan. In addition, the MoI is also responsible for the Afghan Special Narcotics Force, the Counter Narcotic Police of Afghanistan, and the Afghan Public Protection Force. Many of these areas are supported by civilian specialists whom the IPP Program could not deploy.

Haiti

- Beginning in 2013, three specialized teams were deployed to MINUSTAH. The use of specialised teams was recognized as a best practice by the UN in 2015.Footnote 10The teams drew from Canadian police expertise to provide targeted assistance to MINUSTAH and the HNP to achieve objectives outlined in the HNP Development Plan. Each specialized team has its own Terms of Reference (ToRs) with clear mandates, objectives and linkages to expected outcomes. The duties and responsibilities, along with the necessary skill sets required for each position, are also referenced in the ToRs.

- For the first specialized team, Canadian police officers were deployed to the Community-Oriented Policing Team which was recognized as an area in need of capacity building within the HNP. The primary objectives of the team were to develop and implement a community policing doctrine and national implementation strategy, including training and administration; and to coordinate the community policing work of other partners and police-contributing countries in a manner consistent with the HNP national community policing doctrine. Between February and June 2013, the Canadian-led community policing specialized team ran a bicycle unit pilot project. The objective of this pilot was to assist specialized HNP community policing agents to remain connected with communities and also to deal with the shortage of transportation within the HNP. Three police bicycle units were created during the first phase of the pilot in Delmas, Petion-Ville and Croix des Bouquets, with plans to expand these units throughout the country.

- The objective of the second specialized team, Management Advisory Team, was to follow-up with and provide support to the police officer graduates of the HNP Management Academy in a mentoring function once they returned to their work place. The ultimate objective was to develop the capacity within the HNP Academy to manage the Program of Support for Graduated Commissaires. Finally, the third specialized team, Serious Crime Support Unit, contributed to objectives in the HNP plan to prevent crime and violence, specifically strengthening of the Bureau de Renseignements Judiciaires and strengthening of the Direction Centrale de la Police Judiciare.

- During the evaluation reference period, reporting of activities for all specialized teams was received from Canadian police officers’ Individual Monthly and Quarterly Reports (IMRs/IQRs). While the IPP Program reported on the activities of the specialized teams, the performance measurement component of this reporting was insufficient on outcomes and results.

- Aside from the teams noted above, two Canadian police officers were specifically requested by United Nations Police (UNPOL) to continue the work to set up a centralized office for sexual violence crimes in the HNP Central Directorate of Judicial Police.

- Several interviewees were of the opinion that Haiti is an example of a country where the Program has been meeting mission needs. Nonetheless, a lessons learned exercise conducted by the Program in 2012 noted that the HNP suffers from a shortage of technical expertise, including financial administration, human resources, vehicle maintenance, and forensics. The Exercise further identified the need to better support improvements to the judicial reform process. Interviewees confirmed a need to deploy civilian experts to address, in particular, criminal or intelligence analysts, judicial reform and correctional services. Further, the Program deployment schedule did not always align with the HNP Academy training schedule resulting in rotations during the school year that impacted the consistency in training that students received.

West Bank

- Despite Canada’s modest contribution of police to the EUPOL COPPS and Op PROTEUS, Canadian police officers were seen as effective and were valued for their skills and expertise. They were regarded as culturally respectful and were valued for their emphasis on human rights, gender equality and focus on community oriented policing.

- There were areas where the Program was not able to respond to needs. For instance, EUPOL COPPS requested forensic analysis expertise and justice expertise from Canada which the IPP Program was not able to deliver because these are generally civilian positions as opposed to police officers. The low ceiling on Canadian police deployments into EUPOL COPPS (a maximum of 2 officers) also confined the ability of the Program to respond to missions’ needs. In 2011/12, the Program was not successful in their request to authorize an increase in deployments from two to six officers.

- EUPOL COPPS also requested longer deployments from Canada. It was suggested that 18 months to 2 years may be ideal for a deployment. A few interviewees suggested a period of overlap at the beginning and end of an officer’s rotation in order to minimize the transition period.

Flexibility in deployment duration

As outlined in the IPP Program’s SOPs, the standard deployment length is one year to allow police officers enough time to adapt to the mission environment, achieve substantive work objectives, and prepare for a handover to the next individual. In addition, a one year deployment also enables Canadian police partners to backfill vacant positions. The 12 month deployment length is in alignment with recommendations from the UN report on peace keeping.Footnote 11 Notwithstanding, additional flexibility for both longer and shorter deployments are valued. The evaluation found that relevance and responsiveness to mission need was partially limited by the fixed deployment duration in both the missions of focus and other missions reviewed.

For instance, there were requests to extend deployments to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) mission in Kyrgyzstan and the UN Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL). The Closure Report for the STL alluded to the possibility of considering longer deployments to international courts and tribunals. RCMP also noted in a Steering Committee meeting that higher rank positions often necessitated longer deployments. There was also support to deploy for shorter periods of time between one to six months. One female police officer with young children suggested that shorter deployments, of less than six months, might improve female participation in the IPP Program. The evaluation also found one needs assessment report that was completed under the Stabilization and Reconstruction Task Force (START) civilian deployment since the IPP Program was not able to fund assessments that took longer than one month to complete.

Relevance of civilian deployments

The IPP Program is designed around the way policing is delivered in Canada, which is not always aligned with the police structure in the region where the Program is deployed. The Program’s SOPs stipulate that applicants must be a police officer from within Canada. The police institutions in the missions of focus often carry out responsibilities that are different from those carried out by Canadian police officers, including corrections, fire and coast guard. For instance, the HNP is divided into several specialized policing divisions and are responsible for coast guard and paramilitary activities. The inability of the Program to deploy civilians for these other types of responsibilities may hamper Canada’s ability to meet the full range of mission needs. It also has an impact on the achievement of long term stability as the entirety of the police structure is not being addressed. An external review of the UN Police Division conducted in 2016 affirms the important role civilians can play in the success of missions.

Many interviewees supported the idea of expanding the Program’s ability to include civilian professionals that are typically embedded inside police services, including analytics, communications and forensics experts. A few interviewees felt that having a set number of civilian deployments was important. More people expressed caution that increasing the flexibility of the Program in this way would necessitate consideration of available resources as well as additional effort to avoid duplication with other government programs (notably START’s civilian deployment and the Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program (ACCBP).

Bilateral deployments

Bilateral deployments provide an opportunity to achieve Government of Canada priorities in contexts when there are no multilateral peace support operations, or where the mandate or role played by peace support operations may be limited. Over the reference period, the Program looked for ways to increase its flexibility to deploy bilaterally. Missions to UkraineFootnote 12 and Kyrgyzstan were delivered outside of multilateral organizations. The CPA SOPs notes that such deployments are limited to 5 percent of total officers deployed outside of traditional multilateral peacekeeping missions and peace operations. At the time of analysis, there was no structure in the Program’s governance documents to administer bilateral deployments. In parallel with the policy considerations, bilateral deployments requires additional effort and resources of the IPP Program to plan, execute, and operate functions that are normally the responsibility of multilateral missions (e.g. duty of care, security, policy coherence, negotiation with host government). A few interviewees confirmed that the limit on bilateral missions was perceived as inflexible and problematic.

Record of requests and rejections

Finally, the evaluation could not fully assess whether the IPP Program has met the needs requested since the Program has not comprehensively tracked requests for police to support peacekeeping missions and other forms of assistance (e.g. technical assistance, response to crisis). The Program has developed a tracking table with more recent UN requests and maintains a partial record of approval or rejection for mission contribution requests that are received. This remains a gap given the political sensitivity connected with the Canadian response to such requests and was identified for corrective action in the previous evaluation in 2012.

Finding 3: Anecdotally, the Program referenced domestic benefits to Canada as a result of its participation to CPA missions. The most frequently identified domestic benefit to Canada was the skills that Canadian police officers either acquired and/or enhanced.

In keeping with the objectives of the International Assistance Envelope (IAE), the IPP Program funds are to be used exclusively for the purpose of delivering the IPP Program mandate, particularly for the deployment of Canadian police officers to contribute to initiatives in support of peace, security and justice. While not the IPP Program’s primary function, the Program seeks to maximize the domestic benefits to Canada wherever possible. This includes, contributing to improved domestic policing capacity and improved security in Canada. Within the CPA MOU, the guidance to assessing requests for Canadian police contributions to peace support includes a specific point on considering Canadian domestic policing interests.

Domestic security benefits

IPP Program documents noted instances where the Program contributed to addressing threats posed by drug trafficking, serious and organized crime and national security. The lessons learned report on Haiti noted that the presence of Canadian police officers increased security by increasing the capacity of the HNP to impede/intercept narcotics and human trafficking threats. Similarly, in the Afghanistan missions, domestic benefits were referenced with regards to building the capacity of the ANP to address national security and narcotic threats. Almost half of the relevant interviewees indicated that the international missions helped in reducing crime in Canada.

Domestic security interests, a secondary consideration in the mission selection phase, has been considered more consistently in the past few years. Some of the interviewees noted that domestic needs have not played a significant role in the selection of missions and the link to domestic benefits in mission selection was not documented consistently in memos and Program annual reports from earlier in the evaluation’s reference period. However, a review of more recent documents found that domestic benefits are starting to be considered as part of the IPP mission selection process. The RCMP and PS’s respective International Strategic Framework (ISF) help guide mission selection, decision-making and priority areas with respect to international engagements and IPP deployments. Beginning in 2010/11, PS’s ISF was used to identify priorities based on the principle that international security engagements should complement PS’s mandate to ensure the safety of Canadians is developed in coordination with the department and its portfolio of agencies. This includes identifying specific countries of concern to Canadian national security. In 2014/15, the RCMP also developed an ISF. Evaluation analysis found that for the RCMP’s ISF, four out of six IPP missions in 2014/15 aligned with either a priority or watch list countries. The evaluation found that countries that have a low crime nexus to Canada are not frequently prioritized, whereas countries that have a high crime nexus such as Haiti are prioritized.

Domestic benefits for Canadian police officers

CPA reporting documents noted that the most frequently identified domestic benefit has been the enhanced skills of police officers who have served in an international police peacekeeping mission. Based on the evaluation’s analysis, the skills that were most frequently repeated were cultural awareness, working in positions or with colleagues of higher rank and, managerial skills.

Police are immersed in a cultural experience that vastly differs from that of Canada. Once they return to Canada, with its cultural diversity, deployed officers have a useful perspective. Some interviewees noted that Canadian police officers returned home with a cultural understanding and sensitivity to those ethnic communities they had worked with internationally which enhanced community policing (e.g. Haitian, Somalian and Middle Eastern communities in Canada).

The RCMP Individual Quarterly Reports (IQR) included questions related to skills being utilized and acquired. From 2012 to 2015, 740 out of 891 (83 percent) responses from police officers reference skills that were either utilized or acquired. Of those 740, 81 percent either strongly agreed (25 percent) or agreed (56 percent) that skills were acquired due to their participation in an international police peacekeeping mission. According to this data, the top eight skills acquired by Canadian Police Officers were communication, teamwork, relationship building, strategic planning, leadership, conflict management, people skills and technical policing.

When interviewees were asked whether there were skills gained while on international police peacekeeping missions, the majority affirmed that they had strengthened existing skills. While most were hopeful that their mission experience would help them in the advancement of their careers, some indicated that they were unsure mission experience would be an asset during promotional considerations. Based on interviews, half of the interviewees felt they have benefited from these skills professionally. Although interviewees referenced a correlation between missions and enhanced skills, the evaluators were unable to validate this beyond the IMRs/IQRs and interviews.

4.2 Relevance Issue 2: Alignment with Government Priorities; and, Relevance Issue 3: Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Finding 4: The IPP Program aligned with the GC priorities. The Program was an important tool for advancing foreign policy objectives.

Foreign policy objectives at country level

Canada has a history of active engagement in many countries to which the IPP Program deploys. The evaluation found that the deployments complemented Canada’s foreign policy priorities. The following are examples specific to the missions of focus:

Afghanistan

- The IPP Program deployments to Afghanistan were supportive of Canada’s WoG priorities of promoting democracy, ROL and respect for human rights and contributing to effective global governance and international security and stability. The GC committed $330M from 2013 to 2017 to help sustain the ANSF which directly aligned with the mandate of the IPP Program in Afghanistan. IPP deployments stressed the creation of an ethical police force built upon respect for human rights. The evaluation found that deployments were also aligned with the Ten Year Vision for the ANP, the Afghanistan National Development Strategy, and the GC’s six priorities and three strategic projects for Afghanistan, demonstrating a concerted effort to maintain coherence. Evidence showed that the IPP Program in KABUL made efforts to maintain a direct channel to coordinate with HQ on foreign policy priorities.

Haiti

- The IPP Program in Haiti aligned with the priorities of all three partner departments. In particular, the Program aligned with two of the four GC foreign policy priorities, i.e. ROL and security, and Democratic and accountable government, by increasing the capacity of the HNP to provide security and establishing effective law and judicial institutions. In addition, the Program aligned to GC priorities outlined in Canada’s Strategy for Engagement in the Americas which emphasizes a WoG approach to a secure, prosperous and democratic hemisphere. The Program’s mandate to enhance the capacity and skills of police and reform security institutions in Haiti was related to Goal 2 of the Americas Strategy which aims to address insecurity and advance freedom, democracy, human rights and rule-of-law.

- A common challenge with multilateral missions, including MINUSTAH, is that the international mission has its own strategic priorities and objectives that do not always align seamlessly with GC strategic priorities. At times, Canadian police officers deployed to MINUSTAH were assigned to positions that did not always draw upon their unique skills and expertise. For instance, two Canadian officers with work experience in internal investigative units were not assigned to related duties within MINUSTAH.

West Bank

- The IPP Program in the West Bank aligned with the GC’s international and global security commitments and priorities by contributing to effective global governance and international security and stability and promoting democracy and respect for human rights. Deploying Canadian police to build the capacity and skills of the PCP provided support to the Canada-Israel Strategic Partnerships Memorandum of Understanding. This MOU states that Canada and Israel will work toward greater regional stability and security by continuing to support targeted development assistance and training opportunities relevant for the institutions of the Palestinian Authority.

Foreign policy objectives at regional level

Aside from the missions of focus of the evaluation, through a review of documents, it was noted that the Canadian police deployment to the Community Security Initiative of the OSCE in Kyrgyzstan included support for an anti-trafficking initiative which was aligned to the GC’s regional objective of disrupting drug trafficking out of Afghanistan. Deployments to South Sudan to support police reform recognized that if the new country were to become a failed state, there would be more opportunity for terrorist networks to expand their foothold across the broader Sahel region.

Broader GC priorities in security

The Program aligned well to the broader GC priority of building a safe and secure world through international engagement. The CPA MOU stipulates that international police peacekeeping efforts are to be directly linked to Canada’s foreign policy objective of building a more secure world through the re-establishment of effective public institutions such as law enforcement and judicial systems in fragile and conflict-affected states.The thematic priorities under the IAE are broad and align with a number of GAC funded security programs, including the IPP Program.

Police peace operations continue to be a key tool in the maintenance of international peace and security. PRMNY recognizes that Canadian police deployed in or alongside UN peace operations provide valuable training, development, and leadership opportunities in the UN system. The IPP Program deployments have been able to support the promotion of peace and security, democracy, human rights and ROL while providing Canadian representation abroad.

Broader GC priorities in development

Seven countries to which Canadian police officers were deployed were also countries of focus for Canada’s development assistance. The evaluation found that the Program contributed to two of Canada’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) thematic priorities, specifically advancing democracy and promoting stability and security.

Afghanistan

- IPP deployments to Afghanistan helped build the capacity of the ANP to strengthen women’s participation in politics by increasing awareness of women’s right to vote and ensuring greater security at election polls. To facilitate Canadian development projects, Canadian police officers were able to reach out to local officials and communities on behalf of development officers who were limited by their security protocols.

Haiti

- Haiti is Canada’s largest aid beneficiary in the Americas receiving more than $1.4B in development and humanitarian assistance since 2006. In 2014, Canada’s bilateral focus on Haiti included economic growth and prosperity, democratic and accountable government, ROL and security, and the health and welfare of Haitian women and youth. The evaluation found examples where Canadian police deployments complemented GC bilateral development funding and programming by creating the conditions for longer term development. The continued reform of the HNP contributes to greater stability and security in the country which creates a more stable environment for Canada’s development programming to take place.

West Bank

- In 2014, the West Bank was confirmed as an area of focus for Canada’s bilateral development assistance which provides support to core justice and security institutions to build capacity and improve ROL, complementing the work of the IPP Program in the region.

The IPP Program is a unique tool in the GC’s integrated toolkit for Canada to advance its foreign policy objectives by deploying police officers to fragile states and conflict-affected states. For instance, the evaluation did not find another GC program that can draw upon police officers from over 25 Canadian police partners to deploy abroad.

Finding 5: The IPP Program complemented the GC’s and the international community’s approach to fragile and conflict affected states. However, there is still room to improve coherence by enhancing synergies and increasing coordination in similar thematic areas.

Coherence and complementarity within the Government of Canada

The evaluation found that efforts were on-going to improve coherence and complementarity between government departments, within GAC and between international partners.

Within GAC, coherence is supported by the cross representation of CPA partner DGs in the START advisory committees. There is also a deliberate complementarity between the CPA’s Ultimate Outcome and that of START/GPSF. CPA partners were active in interdepartmental working groups such as the Afghan Task Force, PS’s Portfolio WG on Haiti, and the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) WG.

CPA partners maintain contact with and consult other GAC divisions (i.e. Geographics, Counter-terrorism Capacity Building Program (CTCBP), and ACCBP), particularly when assessing a new mission. The overarching mandate of ACCBP and CTCBP is to enhance the capacity of key beneficiary states, government entities and international organizations to prevent and respond to threats posed by international criminal and terrorist activity respectively. Interviewees confirm that IPP Program deployments are aware of the activities of other GAC programs. They also affirmed that the risk of duplication is diminished because the Program has often deployed to different countries than ACCBP and CTCBP. PS also continues to consult with PS Portfolio agencies (i.e., CSC, CBSA, CSIS) to determine relevance and interest in new missions. A number of interviewees noted that cooperation among Other Government Departments (OGDs) was apparent. The missions of focus demonstrate coherence with other GC programming and contribution to WoG strategies.

Afghanistan

- Canada’s engagement was closely coordinated across OGDs to ensure a coherent GC approach. PCO established ‘community practice committees’ for each of the six GC priorities in Afghanistan and these WoG committees met on a regular basis to report on benchmarks. The Ambassador in KABUL was briefed on a daily basis on GC programming and there were regular meetings with management and Canadian police officers to update mission staff. There was also a specific position in KABUL through which the IPP Program coordinated police deployments and ensured that positions aligned with GC priorities.

Haiti

- Correctional services and the coast guard fall under the responsibility of the HNP. Canadian police officers coordinated with CSC in order to develop corrections plans together. GPSF funded the procurement of patrol boats for the Haitian Coast Guard and Canadian police officers provided the training. Canadian development funding supports the Initial Training and Professional Development for the Haitian National Police's Managerial Staff (FIPCA-PNH) Project. The Project aims to train HNP managers and specialists in line with the professionalization of the HNP being a key objective of the HNP development plan.

West Bank

- IPP deployments to the West Bank supported Canada’s WoG approach in the region, in part, by deploying a Canadian Police Officer alongside Canadian Forces to Op PROTEUS to enhance coordination. Deployed police officers were regularly invited to briefings with other Canadian representatives at RMLAHFootnote 13 to share information.