Evaluation of the International Humanitarian Assistance Program, 2011/2012 to 2017/2018

International Assistance Evaluation Division (PRA)

Global Affairs Canada

December 20, 2019

Table of contents

Executive summary

During the evaluation period (2011/12 to 2017/18), Canada was a consistent and respected humanitarian donor that responded to needs in humanitarian crises. It was recognized as timely, flexible and principled. Its humanitarian spending has declined in relation to other donors over the period. It could further increase its effectiveness and strengthen its role in the global humanitarian policy sphere.

The IHA Program (IHA) responded quickly and effectively in rapid-onset crises; increasing its use of drawdown mechanisms and benefiting from rapid approval processes that are unique to IHA and essential for humanitarian results. Conversely, its means to respond to protracted crises could be streamlined. IHA introduced a number of measures to improve performance and enhance flexibility, such as multi-year funding, reduced earmarking and greater support for pooled funds. However, the annual project selection process for protracted crises was unnecessarily burdensome for IHA staff and partners. There were also significant departmental barriers inhibiting work in the humanitarian-development-peace nexus in protracted crises. While staff in the department’s different program streams demonstrated nexus thinking and cooperated informally, there was a lack of overall departmental guidance on the nexus, and the process constraints of different program streams made cooperation difficult. The department has an opportunity to create a better nexus response, guided by Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy, the Grand Bargain and the OECD’s DAC Recommendation on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus.

IHA’s profile and contributions to global policy work were perceived by global actors to have diminished in recent years. This comes at a time when the humanitarian system is more strained by greater needs, increasing pressures of protracted crises, growing risks of the politicization of humanitarian aid, and the emergence of non-traditional humanitarian actors. Contributing to this decline in policy influence include IHA’s reduced support for humanitarian research and the burden of transactional work that limited the time staff had available for learning, analysis and policy work.

Finally, IHA staff (and staff in diplomatic missions that support IHA) would benefit from structured guidance and training, especially in light of the rotational staffing environment.

Summary of recommendations

Department-level

- 1. facilitate a predictable humanitarian budget

- 2. clarify responsibilities of departmental actors with respect to the humanitarian-development-peace nexus

Branch-level

- 3. review the organizational structure of IHA to enhance effectiveness and efficiency

- 4. develop an action plan to advance Canada’s humanitarian policy priorities

Program-level

- 5.streamline partner selection and grant management

- 6. clarify criteria for project selection and expectations for multi-year funding

- 7. develop training and guidance packages

- 8. formalize engagement of departmental staff at missions and in other branches

- 9. strengthen monitoring and evaluation capacity and data use for decision-making

- 10. invest more in knowledge generation, including funding research, innovation and experimentation

Canada’s humanitarian response

Global Affairs Canada is the Government of Canada’s lead in responding to rapid-onset and protracted humanitarian crises and in coordinating a whole-of-government response in the event of a catastrophic disaster abroad.

Within the department, IHA is responsible for humanitarian policy and programming. IHA’s mandate is to save lives, reduce suffering, and increase and maintain human dignity for populations experiencing crisis. The Director General within the Global Issues and Development Branch leads a 30-member team to deliver on this mandate.

Canada’s humanitarian assistance is designed to be flexible and to respond quickly to the needs of affected populations, with particular focus on those most in need—regardless of Canada’s political or other interests.

Canada disbursed over $5B in humanitarian assistance between 2011/12 and 2017/18, consistently making it one of the 10 largest humanitarian donors, with one of the highest proportions of official development assistance (ODA) directed to humanitarian assistance.

Apart from providing sizeable financial contributions, Canada is also known for:

- being a founding member and proponent of Good Humanitarian Donorship (GHD) Principles in Practice (2003)

- leading the renegotiation of the revised Food Assistance Convention (2013)

- committing to the Grand Bargain and co-leading its workstream on multi-year funding (2016)

- promoting gender-responsive humanitarian action through the Feminist International Assistance Policy and G7 Presidency (2017)

- ratifying major international conventions on humanitarian law and advancing UN frameworks such as the voluntary Global Compacts on Refugees and Migration (2018)

Other departmental programs coordinate closely with IHA—notably the Peace and Stabilization and Development programs. Staff in Canadian missions directly support IHA, and in two instances a Development program managed humanitarian assistance (West Bank and Gaza, ongoing; Afghanistan, 2009-2012).

During the evaluation period, Canada was an active participant and donor in the international humanitarian system, with high regard for principled humanitarian action.

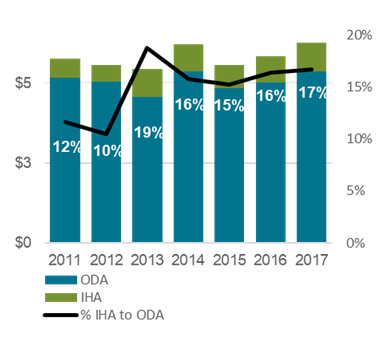

Total Government of Canada ODA funding for humanitarian assistance (billions)

Text version

Percentage of international humanitarian assistance to official development assistance: 12% (2011), 10% (2012), 19% (2013), 16% (2014), 15% (2015), 16% (2016), 17% (2017)

Source: Statistical Reports on International Assistance, in $Can, Global Affairs Canada, 2011/12 to 2017/18.

IHA’s response to the changing context

IHA adapted its response to the changing global humanitarian situation as well as to system-wide reforms and new government commitments over the evaluation period. IHA has increased its contributions to country-pooled funds, increased its transparency and scaled up the use of cash. Importantly, Canada remains ahead of Grand Bargain targets on reduced earmarking and multi-year funding.

There has also been organizational change: IHA integrated the humanitarian policy responsibilities of the Peace and Stabilization Operations Program, and slightly increased its overall staffing levels. IHA currently has three divisions responsible for: policy and institutional relationship management; humanitarian response programming; and humanitarian coordination and natural disaster response.

The evaluation period saw a global increase in humanitarian operations and major reforms in the humanitarian system.

Globally, the period was characterized by:

- a doubling of the global humanitarian funding requirements (from US$9B in 2012 to US$25B in 2018)

- conflict becoming the major driver of need, causing large, prolonged displacements

- concentration of funding in 4 complex conflict crises, centre of gravity shifting from south of Sahara to the Middle East

- emergence of new donors (Gulf donors, BRICs, private donors) and partners

Important humanitarian reform initiatives included the World Humanitarian Summit, resulting in the Agenda for Humanity, the Grand Bargain, the New Way of Working (2016), and the Global Compacts on Refugees and Migration (2018). Also, new funding arrangements (Global Concessional Financing Facility, IDA 18, disaster risk insurance) were negotiated in this period.

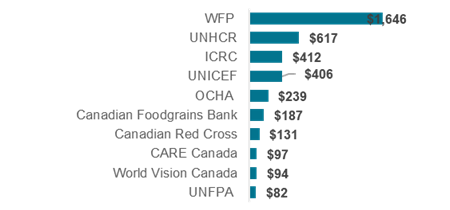

Top implementing partners, in $M USD

Text version

10 partners held 79% of IHA disbursements: $1,646 (WFP), $617 (UNHCR), $412 (ICRC), $406 (UNICEF), $239 (OCHA), $187 (Canadian Foodgrains Bank), $131 (Canadian Red Cross), $97 (CARE Canada), $94 (World Vision Canada), $82 (UNFPA).

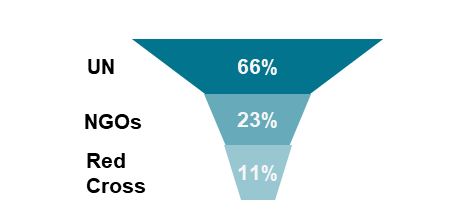

Programming channels

Text version

UN organizations received two thirds of IHA funding; the proportion of NGO funding has gradually increased since 2011/12: 66% (UN), 23% (NGOs), 11% (Red Cross).

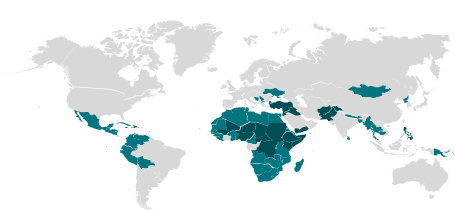

Geographic coverage (105 countries)

Text version

IHA provided funding globally through its core and pooled funding, and through country-specific projects.

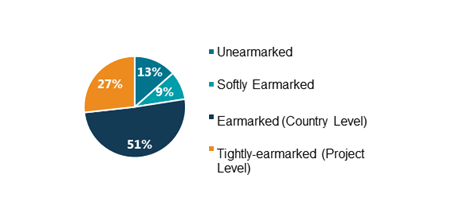

Fund earmarking

Text version

Three quarters of IHA funding afforded partners some flexibility in managing their crisis responses (meeting Grand Bargain targets): 51% (earmarked [country level]), 27% (tightly earmarked [project level]), 13% (unearmarked), 9% (softly earmarked).

IHA response model

This model represents a snapshot of the current IHA program that manages Canada’s response to rapid-onset and protracted humanitarian crises. Until 2013, humanitarian policy work was led by the Stabilization and Reconstruction Unit of the former Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT), while programming was managed by the IHA unit of the former CIDA. Following the merger of DFAIT and CIDA in 2013, the majority of policy work was redirected through the new Humanitarian Assistance Program of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD). Final consolidation of the full suite of humanitarian work was completed in 2018, with all programming and policy work now housed within IHA.

Inputs

Strategic framework

- global treaties ratified by Canada

- international frameworks and resolutions endorsed by Canada

- Government of Canada (GoC) acts, policies and regulations

- GAC processes

Funding sources

- annual base and transfers within GAC authorities

- International Assistance Envelope (IAE) Crisis Pool (max $200M/year)

- GoC strategies through memoranda to Cabinet

- unconditional transfer payments (grants)

Structure and staffing

- HQ-based team with divisions: policy/ institutional relations, programming, natural disaster response1

- some deployment capacity

- regional presence through mission support2

Activities

Policy engagement

- participation in executive and donor coordination bodies

- participation in international meetings and negotiations

- thematic advocacy

- institutional engagement

Response mechanisms

- responsive funding to emergency appeals

- core contributions to multilateral organizations and pooled funds3

- GoC civil-military response4

- drawdown funds5 and stocks for rapid onset emergencies

- country allocations for protracted crises6

- matching funds

Accountability and learning

- project monitoring

- multilateral assessments (MOPANs)

- some support for research and methods partners

IHA response model

Notes:

- Program management structure grew from 1 EX-2, 1 EX-1 and 4 deputy directors to 1 EX-3, 2 EX-1 and 6 deputy directors from 2011 to 2018. The number of divisions fluctuated between 2 and 3 (current) and the number of units between 4 and 6 (current). The organizational chart remained stable at 30 FTEs, but early years saw many vacancies. Staff positions became rotational on a 3-year basis in 2015. Overseas positions of 2 Program representatives (Geneva and Rome) and 1 pilot position in Africa were removed in 2012.

- Deployment of program staff, Canadian Disaster Assessment Team (CDAT), experts through CANADEM and UNDAC, Canadian Red Cross’s Emergency Health Response Units.

- Contributions to UNHCR, OCHA, WFP, ICRC, Canadian Red Cross, Canadian Foodgrains Bank and pooled funds (OCHA-managed CERF and country-based pooled funds, WFP’s Immediate Response Account and WHO’s Contingency Fund for Emergencies).

- Deployment of military assets and the Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) made up of Canadian Armed Forces members and civilian experts, upon CDAT’s recommendation.

- Emergency Disaster Assistance Fund (EDAF) with the Canadian Red Cross; the Canadian Humanitarian Assistance Fund (CHAF) with the Canadian Humanitarian Coalition; the Canadian Foodgrains Bank, which allocates funding to its member churches and agencies; and CANADEM’s humanitarian roster.

- Made primarily through an annual allocation process, with partners pre-qualified for funding. NGO proposals and UN and Red Cross appeals are reviewed by Program officers. Allocations are first made at country level, then project level. Decisions are provided in a memorandum to the Minister for approval. Off-cycle programming is handled during the year.

Methodology

Evaluation questions

Responsiveness

- Given the changing humanitarian context, to what extent has the Program’s delivery model remained fit for purpose?

Results and value added

- To what extent has the Program achieved its results? This includes the extent to which the Program has contributed to reducing suffering, increasing and maintaining human dignity and saving lives in populations experiencing humanitarian crises.

- To what extent has the Program delivered gender-responsive humanitarian assistance that addressed the unique needs of women and girls in crisis situations?

- In what ways has the Program complemented and added value to the global humanitarian response?

Delivery and the way forward

- What have been the lessons learned for improving coherence among humanitarian, development and stabilization programming?

- To what extent has the Program applied the principles and practice of Good Humanitarian Donorship? This includes the extent to which assistance has been needs-based, timely, principled, neutral, flexible and supportive of local capacities.

- What have been the lessons learned of implementing and scaling up innovations in the humanitarian sector?

Methodology

All findings in this report have been triangulated across multiple lines of evidence.

Case studies

Four cases were conducted to examine the department’s capacity and ability to deliver humanitarian assistance at the field level in different types of crises.

The case studies involved:

- a) field visits with direct observations of project sites; interviews with field staff of partner agencies, Canada’s missions and country government officials; consultations with affected populations (Jordan and Bangladesh)

- b) desk-based studies that included document and literature reviews; interviews with representatives from partner agencies and Canada’s missions (Somalia and hurricanes Irma/Maria)

Relevant information from the Philippines, Colombia and Ukraine country evaluations was used as additional case study material.

Analysis of humanitarian disbursements

Assessment of OECD, OCHA, departmental and Program data to profile and examine Canada’s IHA investments and contributions to the global response.

Key stakeholder interviews

Semi-structured individual and small group interviews:

- Global Affairs Canada staff: IHA Bureau, UN agency staff, mission staff and senior officials

(N=45) - Partner representatives: UN, Red Cross, Canadian and international NGOs (N=25)

Survey to heads of aid at Canada’s missions

An electronic survey was administered to current heads of aid covering Canada’s 30 largest IHA-receiving countries. The survey aimed to document missions’ level of effort in supporting IHA and their relationships with the IHA Bureau. Response rate of 76% (N=22)

Appeals and media analysis

Statistical analyses were completed to examine relationships between a) Program country allocations and UN appeals; b) Program country allocations and Canadian media coverage of humanitarian crises in funded countries.

Environmental scan of other donors’ IHA practices and GAC’s alternative IHA delivery

Literature review and follow-up interviews with representatives from 6 other country humanitarian donors (Australia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom). Data were extracted using a developed IHA program model framework to identify donor practices in humanitarian assistance and to compare Global Affairs Canada’s program delivery to models used by other donors.

GAC’s bilateral IHA delivery in West Bank and Gaza and Afghanistan was reviewed through published evaluations and interviews with staff.

Literature and document review

The following departmental documents were reviewed: acts and policies; planning/strategy documents; briefing notes/memos; evaluations, audits and reviews.

Grey and academic literature was examined, including UN publications, ALNAP documents, global humanitarian assistance reports, etc.

Responsiveness

Canada was a consistent, significant and principled humanitarian donor that aligned its allocations with international appeals for funding.

While more than one half of humanitarian funding traditionally came from a small number of donors (the United States, the European Commission, the United Kingdom and Germany), Canada was consistently part of a second tier of large donors.* Its country-level funding allocations were aligned with the needs as expressed in UN appeals. It was a major contributor to several global rapid-response pooled funds and established drawdown funding mechanisms to enable Canadian partners to respond rapidly to small and medium-scale crises. Canada also increased support for country-pooled funds that provide more opportunity for local actors. IHA had robust procedures to coordinate civil-military response to natural disasters and led a whole-of-government approach to address several large crises.

Apart from its sizeable financial contributions, Canada was viewed as a consistent and principled humanitarian donor, providing assistance to a range of complex crises. It ranked highly in adherence to humanitarian principles in third-party assessments. Canada actively supported the strengthening of global humanitarian policy frameworks and reiterated its commitment to international humanitarian laws and principles in its foreign policy statement.

* Canada, Denmark, France, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland each spent between US$3B and $6B on humanitarian assistance between 2011 and 2017.

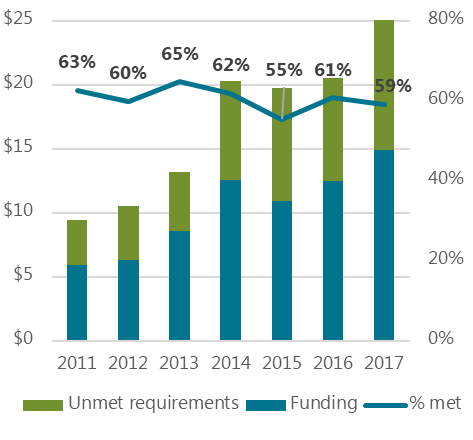

Canada’s humanitarian budget grew in response to increasing global humanitarian need but saw annual fluctuations.

Global humanitarian response funding has more than doubled since 2011, with most donors struggling to keep up with the demand. The steep rise in humanitarian needs was led by 4 large-scale protracted crises that have resulted in long-term mass displacements (Syria, Yemen, South Sudan, Iraq). In response, Canada’s humanitarian budget also grew over time. But without a dedicated envelope of funding that met the level of humanitarian actual expenditures until Budget 2018, the humanitarian budget fluctuated each year. Canada’s share of global funding has also diminished in recent years, affected by a 20% weakening of the Canadian dollar against the US dollar.

Principled humanitarian action remains essential in light of the growing gap between humanitarian needs and available resources, the increasing risks of politicized emergency responses, and the emergence of new actors who do not share the core Good Humanitarian Donorship principles.

Global funding trends

Text version

Percentage of funding which met the funding requirements: 63% (2011), 60% (2012), 65% (2013), 62% (2014), 55% (2015), 61% (2016), 59% (2017)

Source: Development initiatives, based on UNOCHA FTS, UNHCR data and OECD DAC data, in US$ billions.

Response capacity

The Program was successful in securing funding to meet needs. A large proportion of the budget came from supplementary government funding sources designed to respond to large-scale crises.

Each year, IHA’s initial budget reference level was well below its final expenditures, and much of IHA’s regular efforts were focused on securing this remaining balance of funds. IHA benefited from additional GoC allocations, including government-wide and nexus-oriented strategies (e.g. Canada’s mission in Afghanistan, Middle East engagement strategy), and the International Assistance Envelope Crisis Pool mechanism. IHA accessed the Crisis Pool for large crises that exceeded the Program’s funding ability in seven of the past eight years.

In Budget 2018, Canada committed to creating a dedicated pool of funding for humanitarian assistance. Budget 2019 projected the envelope at $788M for 2019/20, accounting for all sources previously allocated to the department. The department continues to work on operationalizing this commitment.

IHA has fine-tuned its tools to provide timely humanitarian response.

IHA introduced tools and processes for better reach and responsiveness. These processes were characterized by a focus on grant funding, higher levels of delegated authority, accelerated decision-making, and reliance upon a relatively small number of highly experienced partners. Together, these enabled timely response. During the evaluation period, IHA has worked to further improve its quick-response tools, and in 2013/14 created a new mechanism—a drawdown fund with the Humanitarian Coalition, a Canadian organization, for quick activation of funding to small and medium-sized crises.

Over time, a greater proportion of the IHA budget was pre-committed to funding specific large-scale protracted crises, thereby decreasing IHA flexibility to respond to emerging needs or forgotten crises.

Changes over time in the proportion of funds already committed or available for Global Programming

Text version

Percentage of funds available for Global Programming, rather than committed to Core Support or a Select Crisis: 64% (2011/12), 74% (2012/13), 70% (2013/14), 63% (2014/15), 45% (2015/16), 33% (2016/17), 23% (2017/18)

Several donors published multi-year expenditure frameworks for development assistance that included projected allocations for humanitarian assistance. For example, the Expenditure Framework for Danish Development Cooperation, 2019 to 2022; the Dispatch on Switzerland’s International Cooperation 2017 to 2020; the Netherlands’ Homogeneous Budget for International Cooperation, with 2019 to 2023 estimates.

Like the global humanitarian system, IHA is designed to respond quickly to disasters but is not well adapted to respond to protracted crises.

IHA’s quick decision-making processes, drawdown funds, rapid deployment capacity, and alignment with the UN’s programming cycle were effective in its response to natural disasters such as the Pakistan floods, Typhoon Haiyan (2013), the Nepal earthquake (2015) and the Caribbean hurricanes. However, the majority of crises to which IHA responds stem from conflict. In 2018, only one of the 30 global appeals was for a natural disaster. Current conflicts are complex and continue for more than 5 years, requiring responses that integrate humanitarian, development and stabilization programming. IHA has worked to strengthen its response tools for protracted crises following the 2014 Auditor General of Canada’s recommendations, and increased multi-year funding and contributions to country-based pooled funds. In some cases, IHA is working informally with other GAC program streams on a collaborative response.

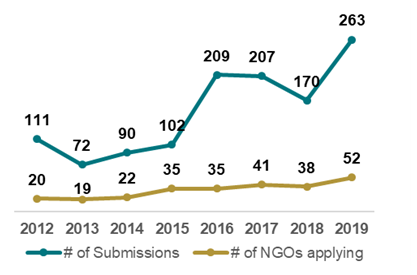

Programming processes for protracted crises were heavy and increased the level of administrative burden on staff and partners.

IHA used UN and ICRC appeals to inform both its multilateral allocations and NGO selection of submitted project proposals for funding through the annual consolidated appeals process (CAP). The CAP process represented the bulk of the IHA officer workload. For the 2017 to 2019 CAPs, each staff member reviewed submissions from 22 NGOs, on average. The top 10 NGOs submitted an average of 9 proposals per CAP, covering 15 countries, and interacted with 9 IHA staff. NGO partners were dissatisfied with the effort and time required to prepare each submission—citing increases in proposal requirements without the accompanying preparation lead time and a lack of articulated IHA priorities to anchor project design.

While IHA consolidated the management of its fund tracking to UN agencies, its NGO partner relationships continued to be managed at the individual project level. Most funding went towards components of partner programs that were supported by multiple donors. The percentage of multi-year funding to NGOs increased in recent years, but the impact of this on the volume of administrative transactions was small.

The number of partners increased over the evaluation period from 20 to 47, yet resources were concentrated among only a few.

The top 10 IHA partners accounted for $3.8B (79%) of all disbursements over the evaluation period (consolidation to UN agencies).

CAP NGO Submissions by year

Text version

Number of Submissions: 111 (2012), 72 (2013), 90 (2014), 102 (2015), 209 (2016), 207 (2017), 170 (2018), 263 (2019)

Number of NGOs applying: 20 (2012), 19 (2013), 22 (2014), 35 (2015), 35 (2016), 41 (2017), 38 (2018), 52 (2019)

The number of NGO submissions increased over time, with major increases in 2016 when IHA began accepting proposals from international NGOs, and in 2019 when IHA introduced a two-step process (concept note step in addition to the proposal.

IHA’s partners implemented 993 projects and recorded as over 3,400 entries within the IHA tracking system.

There was a lack of clarity in the process for allocating resources within the CAP.

Statistical analysis confirmed that IHA’s allocation of resources to crises was strongly aligned with the size of UN appeals. There were no strong links among IHA staff analyses concerning the quality and merit of proposals and final funding decisions, revealing a lack of documentation regarding the other factors that led to funding decisions. Efforts to document decisions and processes have been put into place. The evaluation found that gaps remained, and it was difficult to identify how lessons learned and evidence were integrated into the decision-making process. The challenge of documenting resource allocation was experienced by all donors. Some donors improved this by holding workshops where teams discussed options and decisions openly.

IHA’s small team of skilled staff developed deep knowledge of humanitarian work but had limited time for higher-value analysis, research, policy engagement and knowledge-sharing.

IHA staff levels remained consistent at approximately 30 FTEs over the 7-year period, while its responsibilities and budgets increased. There were weaknesses in human resource succession planning (highlighted in the 2019 IHA audit). IHA was successful in recruiting short-term staff externally, but experienced difficulties in attracting and retaining departmental staff with the required humanitarian skills and experience through the internal rotational channel.

IHA staff responded to departmental requests to review and create briefing materials for meetings, public events and speeches. While the number of briefings initiated by IHA was moderate (in 2018, IHA produced 54 event recommendations, 18 memoranda and 32 meeting notes), their contribution to the department’s other briefing products was significant. Some IHA officers reported spending up to 70% of their time ensuring that internal and public documents accurately reflected IHA’s vision and activities.

Heavy workloads meant that there was little time for exchange among team members. This situation was similarly reported by other donors with specialized humanitarian units. The administrative burden contributed to a diversion of effort away from internal and external collaboration, and knowledge work.

IHA’s human resource vulnerabilities included staff rotation that coincided with IHA’s annual CAP and with hurricane seasons; limited training and guidance tools available for new staff and mission humanitarian focal points; limited resources to monitor funded projects and partners; and inconsistent information management practices.

IHA leveraged mission resources to inform its decision-making but lacked mechanisms to formalize expectations and integrate field knowledge.

IHA staff were HQ-based (except for periodic monitoring visits) and relied on support from Canada’s diplomatic missions to represent their interests at country level. All but one of the surveyed missions dedicated time to supporting Canada’s humanitarian assistance. They rated their involvement as essential (68%) to IHA operational success.

In a survey for this evaluation, the level of satisfaction of mission collaboration with IHA varied. Those missions with larger IHA disbursements reported less satisfaction and tended to involve more mission staff—primarily development officers—on the humanitarian file. One third of missions reported receiving extensive guidance from IHA, while another third reported receiving little or no guidance. Mission staff in IHA target countries are not systematically provided with humanitarian training. Case studies demonstrated that larger emergency responses had larger impact on mission resources. In some cases, missions’ humanitarian-related work was complementary to their other engagements and was mutually beneficial—opening opportunities for work within the humanitarian-development nexus. Both missions and IHA staff agreed that understanding of field expectations and responsibilities was not sufficiently clear and that many of the relationships were personality-driven.

Missions in crisis contexts reported dedicating, on average, 0.7 FTEs to support IHA. A total of 21 FTEs supported 30 countries with large IHA allocations. Missions reported the following activities (% of missions):

- attending coordination meetings (91%)

- reporting on context to IHA Bureau (91%)

- providing logistical support for field visits (86%)

- reviewing partner submissions (82%)

- monitoring Canada-funded projects (73%)

- liaising with host governments (73%)

Some Canadian missions participate in the formulation of country-level humanitarian action plans.

Few humanitarian donors have a sizeable, dedicated in-country presence that enables them to gather contextual knowledge, participate in country-level coordination structures, build relationships with national actors and provide oversight of humanitarian operations. Other donors use a range of practices to gather field knowledge, in addition to partner reporting and periodic field visits made by HQ staff. These practices include:

- hiring consultants locally through field support service units at missions (e.g., GAC’s humanitarian assistance delivered in West Bank and Gaza, and formerly in Afghanistan)

- gathering intelligence from donor-funded experts deployed from third-party-managed rosters to support global humanitarian operations

- formally establishing humanitarian focal points at missions, with focal points’ level of effort and responsibilities negotiated annually by the humanitarian unit and heads of mission

- sharing lessons through annual field days, to which humanitarian focal points are invited (e.g. Sweden)

- assigning a small number of humanitarian staff to missions in key regions (e.g. Australia, the Netherlands)

- hiring third-party monitoring agencies (e.g. in the U.K) as a remote management tool, especially in conflict contexts; these could be multi-donor efforts

- contracting private-sector partners to provide logistical, technical and administrative support to humanitarian operations, including short- and long-term field deployments of humanitarian advisors from a roster (e.g., the U.K.’s contract with Palladium International Ltd., financed from the aid budget)

Alternative delivery models

Many donors adjusted humanitarian assistance delivery in response to global commitments. This included a shift towards multi-year frameworks or partnerships, and greater support to pooled funds.

All donor countries studied (Australia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom) had a stand-alone humanitarian policy or an international assistance policy framework that reinforced humanitarian principles and international humanitarian and human rights law, as well as commitments from the World Humanitarian Summit. Many of these donors have adjusted their humanitarian assistance delivery to align with these commitments. Adjustments were particularly evident in the area of Grand Bargain workstreams led or co-led by each donor (Canada is co-leading the workstream on multi-year funding).

Donors studied were divided between two main humanitarian delivery types, field-based and partner-based, with some a mix of the two approaches. All donors have moved towards greater partner flexibility and predictability by reducing earmarking and introducing multi-year arrangements with partners or coalitions. Multi-year strategic partnerships often had intensive due diligence assessments upfront and then less management during project implementation. Of the 6 donors studied, Canada is closest to Sweden in its focus and management practices. Following its 2010 and 2016 evaluations, Sweden worked to address limitations of the mixed model by formalizing relationships with mission staff, introducing greater transparency and results orientation, and simplifying grant administration.

Humanitarian literature distinguishes between two ways donors organized their humanitarian operations: field-based and partner-based.

The field-based model is typically employed by large humanitarian donors with significant field presence and public country-level humanitarian strategies. These donors typically allocate funding on a project basis, and directly/closely monitor project implementation. EU is the exemplar.

The partner-based model is often employed by donors who manage their humanitarian assistance with a small team from HQ. They rely upon strategic partnerships with trusted organizations who have been through extensive due diligence controls upfront, after which the donor is hands-off at the project level while continuing a dialogue on geographic and thematic priorities. Denmark is the exemplar.

Partner-based (Denmark, the Netherlands, Australia)

- focused on partner capacity and processes

- grounded in trust and upfront due diligence as well as periodic partner assessments

- lean HQ teams

- use of strategic partnerships with partners or coalitions/consortiums

Mixed (Canada, Sweden, Switzerland)

- combines elements of both models

- concerned with partner operational capacity and quality of proposals

- different donors deal with issues of transparency, integrating mission input, monitoring and evaluation in different ways

Field-based (U.K., GAC approach to West Bank and Gaza)

- concerned with programmatic objectives and results (communicated at country level)

- project-based funding

- dedicated humanitarian advisors in the field

- grounded in field presence for context knowledge, project selection and monitoring

Effectiveness

Response effectiveness

Rapid-onset crises

In a rapid-onset crisis, the priority is to obtain a timely assessment of needs and then rapidly provide funds to well-positioned, experienced and trusted partners, preferably already on the ground.

Alert

Notification of humanitarian crisis initiates Canadian response

Assessment

IHA staff is deployed through the Canadian Disaster Assessment Team (CDAT)

Funding tools

Pre-arranged grant agreements are activated and quick approval mechanisms are initiated

Coordination

Military assets and the Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) are deployed if recommended by CDAT

Additional funding tools

If needed, IHA requests supplementary funding from the Crisis Pool and allocates to partners

Implementation

Partners implement the Canadian humanitarian response

IHA coordinates response through interdepartmental coordination group throughout the crisis

As with other donors, limited opportunity for detailed needs assessment and extensive planning due to urgency of life-saving response

Humanitarian programming in rapid-onset contexts

IHA’s tools were well-suited to respond to rapid onset crises.

IHA provided significant support to multilateral rapid response mechanisms and developed Canada-specific tools. Canadian drawdown funds have predefined criteria to enable immediate life-saving interventions. All drawdown funds were viewed as timely, flexible, responsive and effective in kick-starting a response, although some were depleted prior to their end date. The tools were comparable to mechanisms deployed by other donors, except that they did not carry national branding or promote a joint partner response. Case studies confirmed that the drawdown funds fulfilled a critical need in rapid-onset crises.

Government-wide standard operating procedures supported IHA in major natural disasters. The Interdepartmental Taskforce, Canadian Disaster Assessment Team, Disaster Assistance Response Team and military assets generally functioned well as effective Canadian disaster coordination tools.

IHA achieved consistent results, mostly recorded at the output level. Consistent with the global humanitarian system, it did not assess partner or project performance in depth.

IHA had a broad geographic reach. Its support for partners’ multi-country work and drawdown funds enabled IHA to fund activities in small and medium-sized crises. IHA consistently worked with a range of partners (UN, Red Cross, NGOs), increasing the proportion of funding for NGOs over the evaluation period. From 2016 onwards, IHA expanded its partner network to close to 50 implementing partners. Apart from one external evaluation (CFGB in 2015) the only formal assessments of partners were fiduciary risk assessments, and MOPANs for UN agencies.

Partner reporting was focused primarily at the activity and output levels. The global humanitarian system was not designed for measurable long-term outcomes. Case studies revealed some examples where context-specific outcomes materialized, but also where partner performance was uneven and more frequent field-level monitoring would have been beneficial. Most of the visited projects represented contributions towards partner country-level operations and were not donor-specific.

IHA’s mechanisms for immediate response

1. Contributions to UN Immediate Response:

- Central Emergency Response Fund ($29.4M annually; Top 6 donor)

- WFP Immediate Response Account ($6M annually; Top 4 donor)

- WHO Contingency Fund for Emergencies ($1M Annually; Top 7 donor)

- UNDAC roster ($0.4M annually)

2. Canadian tools developed by IHA:

- Canadian Humanitarian Assistance Fund with the Humanitarian Coalition

(10 NGO members; average $3M annually) - Emergency Disaster Assistance Fund with the Canadian Red Cross

(average $3.5M annually) - Canadian Foodgrains Bank

($25M annually) - CANADEM’s Rapid Deployment Fund

(average $1M annually)

Response effectiveness

Protracted crises

In a protracted crisis, assistance should be aligned with a well-justified response plan developed by the humanitarian community. The priority is to select the best-quality initiatives (cost effective, innovative) proposed by experienced partners.

Annual global appeals

Notification of humanitarian crises around the globe

Coordination

Mission staff attend humanitarian coordination meetings and act as focal points for humanitarian partners

Funding tools

Multiyear and unearmarked allocations for core multilateral partners

Annual call for project submissions to pre-approved NGO partners through the IHA consolidated appeals process (CAP)

Coordination

IHA staff consult missions on CAP project proposal selections

Engagement with UN partners through yearly executive board meetings

Additional funding tools

If needed, IHA requests supplementary funding from the Crisis Pool and allocates to partners

Implementation

Partners implement the Canadian humanitarian response

IHA engages with implementing partners at Canadian and international HQ offices

Mission staff represent IHA, participate in country-level humanitarian coordination and engage country-level partner offices

IHA monitors implementation through occasional visits by HQ and mission staff. Partner reporting is relatively light due to grant agreement requirements

Humanitarian programming in protracted contexts

IHA funding allocations for protracted crises were aligned with global appeals at the country level, but the project selection process was labour-intensive and influenced by factors beyond project quality.

The size of UN coordinated appeals was used as an approximation for the relative level of need and as a guide for overall country allocations. However, the translation of overall country funding envelopes into project portfolios was not always straightforward because of the following factors:

- IHA’s quality control mechanisms (financial risk assessment, MHD institutional profile) assessed the partners’ global institutional capacity whereas funding decisions were project-based and would have required understanding of local context, partner standing and field capacity. The relationship between the quality control mechanisms and the project approval process did not connect these two critical elements for success together in a straightforward way.

- IHA staff assessed the quality of submitted proposals, at times in collaboration with mission staff, but many of the assessment criteria were not factored into final decisions.

- IHA actively encouraged multi-year funding proposals for NGOs in select protracted crises but did not articulate its expectations and assessment criteria for selecting multi-year interventions.

IHA staff and partners viewed the CAP as lengthy and resource-intensive. Most partners submitted multiple proposals annually with varying degree of success. Some estimated their level of effort as high as two months for several staff to prepare a proposal and ensure it met requirements (e.g. engagement of beneficiaries into project design, gender analysis). Many NGO partners expressed concern over lack of clarity around expectations, available amounts and final decisions. Case studies also revealed examples where written proposals did not match implemented activities and where more frequent field monitoring would have enhanced the quality of project implementation.

As of 2018, IHA was responsible for five Cabinet commitments: (1) a target of $800M humanitarian assistance annually; (2) Food Assistance Convention commitment of $250M annually; (3) Middle East Strategy pledge of $840M over 3 years; (4) Canada’s Education in Crisis pledge of $400M over 3 years; and (5) the Rohingya humanitarian pledge of $124M over 3 years.

The CAP is a multi-step procedure for NGO project selection that spans a 6-month period:

- CAP launch starts each summer and leads to the publication of the NGO guidelines

- The review stage begins with NGOs submitting concept notes in early fall; IHA then invites successful NGOs to develop full proposals; IHA staff review NGO proposals alongside the UN and ICRC appeals to recommend overall allocations

- Throughout the CAP launch and review stages, IHA analyzes data on the evolving situation to arrive at country amounts

- IHA submits proposed allocations for ministerial approval in February, with funding decisions made public in early spring

Humanitarian programming

Partners viewed IHA’s flexibility and multi-year funding as Canada’s strongest features.

Partners emphasized IHA’s flexibility as its key feature. Flexibility was expressed as providing unearmarked funding (low levels of earmarking) at the global and country levels, rapid consideration and approval of project changes (e.g. due to conflict escalation, weather conditions), or project timeline extensions. Multi-year agreements provided similar benefits to unearmarked funding.

Most NGO partners credited IHA with advancing the Grand Bargain’s multi-year commitment. Partners largely operationalized multi-year funding to enhance operational efficiency (staff recruitment and retention, lower administrative costs), but did not deliberately put into place measures that would provide longer-term benefits for affected populations. Research has shown that these benefits can be achieved when partners plan for multi-year evolution and when large partners sign multi-year agreements with their sub-contracting partners. Further changes to project design and monitoring systems would allow these benefits to be realized more fully.

IHA’s burden-sharing target was not met in recent years.

IHA did not meet its notional target of contributing 3-5% to the global burden share in recent years. IHA remained a high contributor to crises supported by Cabinet commitments. IHA’s budget fluctuations, the exponential growth of global humanitarian needs, and a weaker Canadian currency all contributed to missing this global burden-sharing target.

IHA’s system-strengthening work was limited.

While IHA consistently provided funding for humanitarian coordination, its funding for OCHA and country-based pooled funds was less than that of comparable donors. IHA supported UN capacity through core contributions and Canada’s participation in multilateral agencies’ executive boards. NGO partners expressed the desire for more IHA funding for capacity building, monitoring and evaluation, for themselves and for local NGOs, including in Canada’s priority area of gender equality.

Flexible funding allows the partner to decide what is best in the specific context. Its benefits include the ability to adapt to changing humanitarian priorities (e.g. swift scale-up or drawdown, shift of operations to different sectors or locations), a focus on overlooked or forgotten crises, and reduced costs of transactions with the donor.

Multi-year funding is funding given over two or more years and is typically provided for protracted crises. Partners credited it with lowering operational costs, enabling early response, improving program planning, integrating local capacity building, and promoting coherence with recovery, stabilization and development programs.

During a major disaster, Canada sometimes employs a matching funds mechanism whereby the government sets aside an amount to match public donations to eligible Canadian organizations. Aside from being a fundraising tool, this mechanism also increases public understanding of humanitarian issues. Participating NGO partners reported notable increases in public fundraising when the mechanism was in place but expressed disappointment that matched resources were also allocated to UN agencies.

Humanitarian policy

The Feminist International Assistance Policy provided a general framework for IHA. Some early actions have been undertaken. There is an opportunity for Canada to further the Policy and influence the global humanitarian discourse.

As of 2017, humanitarian assistance has been embedded within the Feminist International Assistance Policy. Concrete IHA actions with regards to the Policy included a requirement for NGO partners to demonstrate gender equality capacity and analysis, and gender-based violence risk analysis, in their proposals. It was too early to tell what these initiatives resulted in. The 2018 OECD DAC peer review noted that IHA lacked specific guidance for achieving Canada’s gender objectives and measuring their achievement. To date, Canada has provided a generalized voice on the importance of gender issues, with stakeholders expressing a desire for IHA to focus on priority setting in the future. The evaluation noted a need to bolster expertise in gender and humanitarian action to deliver on gender objectives.

IHA made important, but diminishing, contributions to global humanitarian policy development despite Canada’s continued standing as a top donor.

Canada, with its large humanitarian investments, was perceived by other donors and global humanitarian actors as neutral and credible. Canada’s most cited achievements in advancing humanitarian policy were leading the renegotiation of the Food Assistance Convention, advocacy and funding for micronutrient fortification, and co-sponsoring UN Security Council Resolution 2286 (2016) (protection of medical personnel in conflict situations).

Stakeholders spoke positively of Canada’s new international assistance policy, with its focus on gender, and political leadership on IHL under its 2018 G7 presidency. However, most stakeholders were unclear of specific activities or knowledge areas that Canada planned to advance, including how Canada intended to operationalize gender-responsive humanitarian action. Canada’s reduced role in the humanitarian policy arena seems to have coincided with restructuring of departmental responsibilities following the merger of CIDA and DFAIT. Many stakeholders were interested in Canada having a stronger voice on the global stage on international humanitarian law, humanitarian system reform and Grand Bargain commitments.

In 2019, Canada published its Action Area policy on humanitarian assistance, Gender Equality in Humanitarian Action. The policy underlines Canada’s adherence to Good Humanitarian Donorship principles and outlines Canada’s priorities and actions in four areas: respect of humanitarian principles and international humanitarian law; prevention, mitigation and response to sexual and gender-based violence; provision of sexual and reproductive health services during humanitarian interventions; and empowerment of women and girls.

IHA’s policy engagement was more reactive to requests than proactive on strategic issues—which limited linkages between policy and programming.

Many IHA staff have strong policy understanding and substantial experience, but significant time was allocated towards activities they regarded as lower-value. Much of IHA’s policy work focused on responding to incoming departmental and external requests for information and input, rather than contributing to global humanitarian policy development. Interviewed IHA policy staff spoke of their desire to develop thematic expertise in key areas of IHA’s mandate and to better address the weak linkages between policy and programming (a challenge shared by other donors). This was particularly relevant for key issues of gender in humanitarian action, accountability to affected populations, and innovation.

IHA’s investments in research, innovation and experimentation were limited and constrained its ability to contribute to the global humanitarian discourse on these topics.

IHA investment in research, innovation and experimentation varied year to year, and totalled 1% of all disbursements during the evaluation period. This was likely a reflection of the budget uncertainty and absence of a formal humanitarian assistance strategy. Most of these investments supported the global work of humanitarian think tanks. Only a few were focused on solving specific policy problems (e.g. Cash Learning Partnership with Action Against Hunger; Last Mile Mobile Solutions with World Vision; development of minimum standards for child protection with UNICEF). Some humanitarian-related innovations, such as disaster risk insurance and financial instruments for refugee-hosting countries, were supported by the department’s development branches.

With one exception (CFGB), IHA did not independently assess or evaluate NGO partners or country responses. Initiatives to share learning from staff monitoring missions or to compare notes on partners did take place but were not structured. IHA did not have an in-house performance measurement or knowledge management unit.

Other donor best practices in supporting research and capacity development of the humanitarian system include the U.K.’s Humanitarian Innovation and Evidence Programme; Sweden’s 3% commitment from the humanitarian assistance budget; the Dutch Relief Alliance’s Innovation Fund, financed by the Netherlands; and Denmark’s strategic partnerships, that allow up to 10% for innovation and up to 30% for flexible programming.

Humanitarian-development-peace nexus

The evaluation revealed significant departmental barriers to effectively bridging humanitarian-development-peace gaps in protracted crises.

Case studies, departmental evaluation findings, and interviews demonstrated the department’s siloed approach to protracted crises. Different program streams plan and assess performance, each with their own objectives, timelines and methods.

Program streams shared information where possible; however, there was little formalized crossover work on a shared vision, joined-up planning, reporting, monitoring and analysis between them. Key challenges were:

Overarching departmental leadership

The department lacked a clear, overarching and leading vision on the nexus to guide all program streams. Program streams working in protracted contexts were left on their own to address the challenges of working on the nexus—creating ad hoc and informal channels when necessary while also advancing their own programmatic priorities within their institutional parameters. Departmental attempts to join up program planning were piloted (e.g. Integrated Country Frameworks) but mostly fell short of true integration and few were formally approved. There is no current overall departmental approach to address the nexus question. While the department-wide Middle East Strategy and Rohingya response achieved some success in bridging divides, very different planning and programming systems inhibited the alignment of programming at the nexus.

Departmental approval mechanisms and nexus financing

IHA’s budget shortfalls, approval criteria and funding mechanisms discouraged the use of humanitarian funding for crossover activities more closely aligned to development goals. Stakeholders confirmed IHA’s emphasis on life-saving interventions, and many were unclear how multi-year funding could be used to address the multi-faceted needs of affected populations in a protracted crisis. Development programs were usually locked into host government priorities and too slow and inflexible to move closer to the humanitarian space.

Nexus is the interconnectedness of humanitarian, development and peace actions. A nexus approach seeks to strengthen collaboration, coherence and complementarity of program streams towards collective outcomes. – Inter-Agency Standing Committee (OCHA)

In February 2019, Canada endorsed the legally non-binding OECD DAC’s 11 recommendations on the humanitarian-development-peace nexus.

- joint, risk-informed, gender-sensitive analysis

- appropriate resourcing to empower leadership in coordination

- political tools and other instruments to prevent crises, resolve conflicts and build peace

- prioritize prevention, mediation and peacebuilding

- put people at the centre of programming

- do no harm and ensure conflict sensitivity

- align joined-up programming with risks

- strengthen national and local capacities

- invest in learning and evidence

- develop evidence-based coordinated financing strategies

- use predictable, flexible, multi-year financing

Despite gaps in the department’s formal approach to the triple nexus, the different program streams initiated nexus-focused activities in an informal and ad hoc manner, with varying levels of success.

In the absence of formal departmental guidance on coordination and complementary work on the nexus, the department’s programs demonstrated numerous examples of attempted nexus programming. Collaboration between program streams was dependant on the availability of development resources, individuals’ willingness to cooperate, and contextual knowledge of the operating environment of a given crisis.

Departmental evaluations and case studies in Colombia, the Philippines, Somalia, Bangladesh and Jordan identified examples where program streams engaged in work that promoted common analysis and complementary activities between streams. Noted nexus-oriented activities included increased information-sharing on conflict drivers, consultation on humanitarian proposals and communication between officers of different program streams. In most cases, experienced and long-standing staff members with deep knowledge of the countries and crises in question facilitated the discovery of cooperation opportunities between program streams.

Canadian unearmarked, multi-year funding contributions to UN agencies provided them the opportunity to align funding with contextual needs. Partners reported using Canada’s unearmarked and multi-year humanitarian funding in areas that required assistance beyond immediate relief and on the development boundary, such as support for resilience and livelihoods, especially in protracted humanitarian contexts. Canada’s support to fragile states and protracted crises necessarily engaged respected NGO partners who provided assistance based on a full view of the needs of affected populations. In some cases, Canada funded the same partners to undertake both development and humanitarian activities through different funding channels.

Dual-mandated partners worked towards nexus solutions in education in Jordan. Programming supported universal education under the Jordan Compact. The combined short and long-term approach was successful and considered for replication in other sectors (health).

Humanitarian

Education for Syrian refugee children

223 UNICEF Makani Centres

Development

Jordan’s MoE Education Sector Plan

UNICEF management of double-shiftschools

The global agenda is focused on bridging the gaps between humanitarian, development and peace programming. Canada has increasingly contributed to these initiatives. Examples of global efforts include:

- innovations to address natural disaster risks, such as disaster risk insurance

- innovative financing for low-to-middle-income refugee-hosting countries

Conclusion

Canada’s humanitarian investments have saved lives, reduced suffering and protected human dignity. IHA staff have strong expertise and substantial experience. Their value could be further exploited if some of their time spent on administrative tasks was freed up for more substantive work. The value of longer-term and nexus approaches in protracted situations is well understood and would be facilitated by a more systematic inter-Branch approach to joint analysis, planning and deliberately complementary programming.

Canada remained an important, responsive and principled donor that continued to address global humanitarian needs. Gaps in global funding requirements, driven by protracted crises with prolonged displacements, have led to a global shift towards more context-responsive and accountable humanitarian action. This presents an opportunity for the department to review IHA’s organizational structure and programming systems so that IHA can strengthen its evidence base and have greater impact.

Canada is widely regarded as a strong defender of Good Humanitarian Donorship, and other donors look to Canada to carry more policy weight. For IHA to free up staff time for more knowledge work, including deepening their understanding of country contexts and program performance, and to achieve this with a similar staffing level, IHA would need to reduce officers’ volume of project and information transactions and streamline business processes (especially the CAP). Some reflection on the role of mission staff in supporting humanitarian objectives on the ground could also improve the delivery of IHA programming, particularly in a protracted crisis context.

In countries with major conflicts or large protracted crises that are holding back national development, there is appreciation across Program streams that they can do better if they work together on the humanitarian-development-peace nexus. However, the existing planning and programming systems of the department do not lend themselves easily to such collaboration.

Like most of the humanitarian system, Canada’s responses have been very effective in rapid-onset disasters, but its processes are less well-suited to protracted situations. Canada remains highly respected as a humanitarian donor, and both international and Canadian partners would like Canada to engage more proactively in global humanitarian reforms, including by implementing initiatives to better address the humanitarian-development-peace nexus in protracted situations and to better address gender issues.

Considerations

The evaluation identified best practices that the department and IHA could consider in order to improve their operations.

Humanitarian-development-peace nexus

Recognizing the interconnectedness of challenges found in protracted humanitarian crises, the department in these contexts could consider approaches outside the traditional programming silos. The department could consider starting from a department-wide analysis of fragility, and then decide a clear division of labour based on comparative advantages.

Field support

Canada’s missions have played an important role in the achievement of humanitarian objectives. IHA could consider formally capitalizing on their field knowledge by a pilot of assigning regional humanitarian specialists, or by formalizing relationships with select missions through humanitarian focal points, supported by guidance and training for staff in missions.

Strategic funding approaches

IHA could consider moving towards a pooled-fund model to streamline grant administration. This would allow IHA to capitalize on its HQ team experience, existing due diligence processes and preference for a light field footprint while also enabling it to maximize opportunities to increase local ownership of humanitarian responses. In tandem, IHA could deepen dialogue with strategic partners, enabling IHA to pursue its commitments/policy priorities closely with partners and minimize administrative burden. A smaller annual project submission (CAP) process could be used for partners without strategic partnerships, for select large crises, or to provide emphasis to Canada’s priority thematic areas.

Knowledge generation and use

IHA could consider strengthening its results orientation, monitoring and evaluation capacity to better integrate learning into decision-making and give itself a stronger global voice. This could be achieved by more frequent, structured and targeted field visits; formal engagement of Canada’s overseas missions; use of IHA-funded “deployees” and consultants from Field Support Service units; or third-party monitoring schemes (with/without other donors).

Training

IHA could consider formalizing training on humanitarian topics and internal processes for all new rotational staff (and select outgoing mission staff) through the Canada School of Public Service and the Canadian Foreign Service Institute in order to build the department’s common understanding of IHA’s unique workload, approach and tools.

Recommendations and management responses

Evaluation recommendations are organized at three different levels to target existing accountability structures. Recommendations at the IHA Program level include several “quick wins” that could be leveraged to gain efficiencies and improve programming results.

Department-level

Recommendation

1. The Deputy Minister of International Development should clarify the department’s pathway towards achieving a predictable, multi-year humanitarian budget for the IHA Program that is consistent with the Budget 2018 commitment, and would allow for a more strategic and longer-term approach in Program engagement within the global humanitarian system.

Management response

In order to achieve predictability and provide a consistent IHA programming budget in line with Budget 2018, the department will reallocate funding from its traditional core development budget to IHA.

IHA funding allocations will be considered during the 2020 to 2021 Investment Planning Process.

Recommendation

2. The Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Deputy Minister of International Development should clarify expectations and responsibilities of different departmental actors with respect to nexus programming. They should determine roles and responsibilities of programming streams in contexts where several departmental actors are operational. It should identify options to enable better financing across the nexus, and close existing gaps in funding prevention and long-term recovery efforts.

Management response

MFM/IFM/DPD will collaborate on identifying options for a way forward to enhance the department’s approach to nexus programming, including tools, roles and responsibilities, guidance, etc., in line with the 2019 OECD DAC Recommendation on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus. A recommended option will be presented for discussion at Executive Committee.

Branch-level

Recommendation

3. The Assistant Deputy Minister, Global Issues and Development Branch, should review the organizational structure of the IHA Program to ensure that it is fit for purpose in order to enhance the effectiveness of Canada’s humanitarian action and IHA’s ability to be a high-performing learning organization. The reviewed structure should consider optimizing IHA’s access to departmental centres of expertise or building expertise internally.

Management response

The Assistant Deputy Minister, Global Issues and Development, with support from the Program, will review the Program’s structure to ensure it is fit for purpose.

Recommendation

4. The Assistant Deputy Minister, Global Issues and Development Branch, should lead the development of an action plan to advance Canada’s policy priorities as outlined in the 2019 Action Area policy A Feminist Approach: Gender Equality in Humanitarian Action. The action plan should include concrete actions to be pursued in the short and medium terms, reinforce the required sector knowledge and expertise, and include ways to measure results.

Management response

Building on existing work, including the humanitarian elements of the implementation plan for Canada’s Policy for Civil Society Partnerships for International Assistance – A Feminist Approach, the Assistant Deputy Minister, Global Issues and Development, with support from the Program, will develop a plan to advance Canada’s policy priorities as outlined in the 2019 sub-policy A Feminist Approach: Gender Equality in Humanitarian Action.

Program-level

Recommendation

5. The Director General, IHA Program, should identify ways to streamline partner selection and grant management and reduce administrative burden on IHA staff and partners.

Management response

The Director General, IHA Program, will develop and implement options to continue to reduce the number of project transactions.

Recommendation

6. The Director General, IHA Program, should clarify and communicate to NGO partners IHA’s criteria for selecting and prioritizing projects for funding and its expectations for multi-year interventions.

Management response

The Director General, IHA Program, will revise the IHA NGO guidelines to outline Program considerations for selecting projects for responsive programming and to further define expectations for multi-year interventions, and will communicate to partners accordingly.

Recommendation

7. The Director General, IHA Program, should develop training and guidance packages for IHA and mission staff to ensure a continued and consistent level of humanitarian expertise in the department’s rotational environment. The packages could include a focus on theoretical and practical knowledge and skills, be informed by humanitarian field experience, and include mentorship components.

Management response

The Director General, IHA program, building on existing best practices, commits to further develop training and guidance packages for all IHA officers in order to ensure a continued and consistent level of humanitarian knowledge and expertise.

Recommendation

8. The Director General, IHA Program, should develop a strategy to formalize IHA’s engagement with departmental staff at missions and in other branches and communicate it to the implicated missions and branches. The strategy should consider different levels of engagement based on the weight of the in-country humanitarian workload, types of crises and expected levels of field support. It could also include periodic meetings of mission-based focal points with IHA to share knowledge and priorities.

Management response

To enhance collaboration, the Director General, IHA Program, will work with relevant branches and missions in contexts where GAC-funded humanitarian programming is being delivered to identify best practices and shared roles and responsibilities.

Recommendation

9. The Director General, IHA Program, to inform IHA decision-making, should strengthen IHA’s monitoring and evaluation capacity, its ability to use research on global best practices, and the evidence it collects.

Management response

The Director General, IHA Program, will update existing guidance on best practices for the monitoring of humanitarian assistance projects and will enhance IHA’s approach to knowledge management to ensure more systematic, bureau-wide sharing of lessons learned, including from evaluations, and to inform decision-making.

Recommendation

10. The Director General, IHA Program, should make focused investments in humanitarian knowledge generation through increased funding for research, methods development, humanitarian innovation and experimentation.

Management response

The Director General, IHA Program, commits to developing a plan guided by strategic priorities to support investments in research, policy development, innovation and/or experimentation.

Annexes

Annex I. Acronyms

- CAP

- Consolidated Appeals Process

- CERF

- Central Emergency Response Fund

- CFGB

- Canadian Foodgrains Bank

- CHAF

- Canadian Humanitarian Assistance Fund

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- DAC

- Development Assistance Committee

- DFAIT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (Canada)

- DFAT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia)

- DFATD

- Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (Canada)

- DFID

- Department for International Development (U.K.)

- DRR

- Disaster Risk Reduction

- EDAF

- Emergency Disaster Assistance Fund

- FAO

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- FTE

- Full-time employee

- FTS

- Financial Tracking Service of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA)

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GHD

- Good Humanitarian Donorship principles and practice

- GoC

- Government of Canada

- ICRC

- International Committee of the Red Cross

- IHA

- International Humanitarian Assistance

- IRA

- Immediate Response Account of the World Food Programme

- MOPAN

- Multilateral Organisation Performance Assessment Network

- MFA

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- NGO

- Non-governmental organization

- OCHA

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- SDC

- Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation

- SIDA

- Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency

- UNDAC

- United Nations Disaster Assessment and Coordination

- WFP

- World Food Programme

- WFO-CFE

- World Health Organization Contingency Fund for Emergencies

Annex II. Case studies

Canada’s IHA response in Somalia

The delivery of Canada’s IHA in Somalia remained largely unchanged over the 7-year period. In recent years, the Program increased its support to local responders through the country-based pooled fund (Somalia Humanitarian Fund [SHF]) and a greater shift towards 2-year projects. Interviewed stakeholders viewed both of these as important factors to strengthen their capacity to provide a sustained response in communities. Most spoke positively of the Program’s flexibility and access to the drawdown funds, which enabled partners to quickly adapt to changes in the context.

Canada’s contributions in Somalia did not derive from a specific, explicit strategy and were broadly aligned with global appeals and humanitarian principles. Many NGO partners stated that they would like strategy-level information from the Program to better align their proposals with what Global Affairs Canada was attempting to achieve.

Case study respondents highlighted Canada’s reduced in-country presence (Canadian staff, consultants or third party) as a factor that limited its visibility and influence. It also negatively impacted the Program’s capacity to access first-hand information, monitor projects and learn from what was happening on the ground.

Global Affairs Canada’s engagement in Somalia was not expanded beyond humanitarian assistance to reflect growing optimism among donors for the prospect of long-term recovery and a shift towards development. The Program demonstrated interest in multi-year projects, which were used by some partners to address the recovery and resilience elements, including livelihoods, non-emergency health care, and child protection. However, the Program did not explicitly state its expectations on multi-year programming. Several respondents remarked that Canada’s support for development initiatives was missed.

Overall, Canada was viewed by interviewees as a modest and not visible donor in Somalia. Canada was also viewed as unengaged in global dialogues surrounding long-term stabilization and recovery.

The humanitarian crisis in Somalia is multi-faceted and categorized as protracted. Its context includes weak governance, violence, insecurity and civilian protection issues, internal displacement, cyclical droughts and other climatic events. Inadequate access to social services and essential resources, such as basic health care and water, exacerbates populations’ vulnerability.

Canada’s IHA contributions 2011/2012 to 2017/2018:

Consolidated appeals:

- 9th largest donor to Somalia’s CAP (3% of burden share)

- $200M disbursed to 17 partners (62% to UN, 13% to Red Cross and 24% to NGOs).

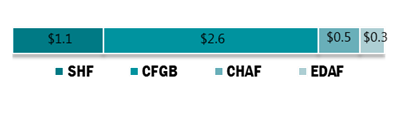

Rapid-onset tools and common funds (in $M)

Text version

$1.1 for SHF, $2.6 for CFGB, $0.5 for CHAF, $0.3 for EDAF

Apart from IHA funding, Global Affairs Canada has limited programming in Somalia.

Canada’s IHA response to the Syrian crisis in Jordan

IHA programming in Jordan had unique characteristics that positioned the Program favourably to achieve short and long-term outcomes. IHA was part of the integrated whole-of-government Middle East strategy that linked humanitarian, development and security/stabilization objectives and guaranteed funding for three years. It also benefited from close collaboration with experienced mission staff, who advanced development programming in several sectors complementary to IHA and provided important input in the selection of project concept notes submitted for funding.

The Program piloted multi-year funding in the Middle East in 2016 and included a two-step project selection process. However, project selection largely followed existing CAP criteria for allocating funds. Little emphasis was placed on the incremental added value to programming outcomes or on exit strategies for interventions that targeted beyond immediate life-saving needs.

Funded partners achieved good results, particularly in education and health sectors; however, the absence of long-term thinking limited overall impact. The Program did not monitor projects outside of brief yearly field visits. Partner accountability mechanisms to beneficiaries focused on resource access complaints rather than improving project design. Some NGO partners collected data outside the UN needs assessment system, which increased the overall quantity of stored sensitive information without corresponding data protection safeguards. Multi-year funding brought about administrative efficiencies but did not change modi operandi in planning or learning from results.

Canada was recognized as an active donor for resilience building and as a promoter of nexus thinking in Jordan. The Program provided flexible funding that allowed UN partners to deliver both life-saving assistance to refugees and longer-term livelihood interventions and economic stability for refugees and vulnerable Jordanians. The Program’s footprint benefited from the mission’s development channels and context knowledge. Mission staff had a notable presence in local humanitarian coordination mechanisms and engaged humanitarian partners regularly. While complementary, this humanitarian work required additional mission effort.

Jordan has hosted an estimated 1.4 million Syrian refugees since 2011, of whom fewer than 700,000 are officially registered with UNHCR. Most Syrians in Jordan live outside refugee camps. Social cohesion and community peace have been important challenges where Syrian and Jordanian communities coexist. Strains on existing social services, coupled with communities’ conflicting perceptions of disparities in benefits, have caused tension and violence. Tensions have mostly centred on access to jobs and affordable housing, as well as on quality education in light of limited and diminishing resources and cramped conditions.

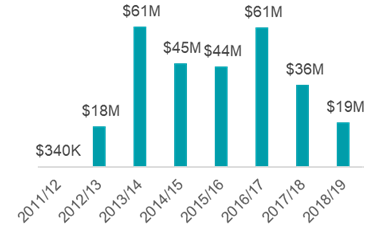

Canada’s IHA contributions to Jordan 2011/2012 to 2017/2018

Text version

$340K (2011/2012), $18M (2012/2013), $61M (2013/14), $45M (2014/2015), $44M (2015/16), $61M (2016/2017), $36M (2017/2018), $19M (2018/2019)

Canada’s IHA response to the Bangladesh-Rohingya crisis