Final Report: Evaluation of the Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Initiative 2010–11 to 2017–18

Final Report

International Assistance Evaluation Division (PRA)

Global Affairs Canada

May 2019

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Since 2010, Canada has played a leadership role in global action to end the preventable deaths of mothers, newborns and children. Canada’s Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH) InitiativeFootnote 1 is a ten-year (2010 to 2020) $6.5 billion commitment aimed at improving the health of women and children in the world’s most vulnerable regions. This represents a significant amount of international assistance resources spanning numerous geographic regions and functional areas.

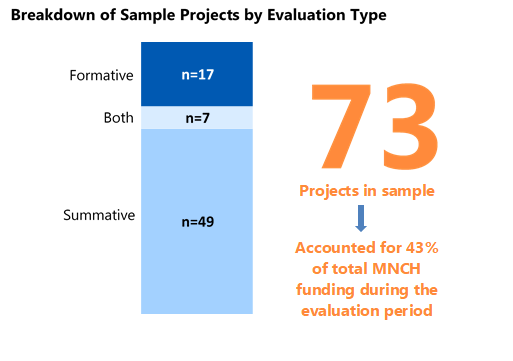

This evaluation of the MNCH Initiative assessed the relevance, effectiveness, sustainability and efficiency of programming in order to inform decision-making and to support policy and program improvements. The evaluation focused on a sample of 73 projects out of a total of 987 projects associated with the Initiative that were funded by Global Affairs Canada from 2010–11 to 2017–18. The sample accounted for 43% of total MNCH funding during the evaluation period.

Relevance

The evaluation found that MNCH programming was relevant because it took into account local and partner-government priorities, and had evolved to better target key gaps, including sexual and reproductive health. Focusing on health systems strengthening was a particularly relevant approach as a strong health system is key to delivering health services and achieving results. At the same time, a need for more emphasis on an integrated, multi-sectoral approach to further address determinants of health and the needs of adolescents was identified.

Results

MNCH projects have been achieving results and a high proportion of the projects examined made progress on achieving their intended outcomes. At the ultimate outcome level, Canada has made a contribution to country-level improvements in child mortality, although maternal mortality remains a challenge in the countries examined. However, overall results for MNCH across all branches could not be aggregated to the departmental level. This was primarily due to a misalignment of performance indicators between the project and the departmental level, inadequate reporting software and IT systems, a lack of technical support for staff, and weak country-level data systems.

Canada was seen as a respected donor with a positive track record in contributing to national-level policy dialogue and donor coordination in the health sector in all countries sampled. Also, other donors recognized Canada as a leader in advancing gender equality and positive changes in gender equality were reported. Global Affairs successfully supported some partners to engage in innovative work, but the Department was less successful at promoting innovation internally.

Sustainability

In terms of sustainability, the Department lacks a reporting mechanism to monitor results after funding ends. Despite this, the sustainment of results was noted for some projects. Some projects incorporated measures to support sustainable results. However, many MNCH results could be at risk without ongoing donor support. This was in part due to challenges at the country level, such as limited partner-government commitment to fund health budgets, and low technical and human-resource capacities. At the project level, limited windows for project implementation also put projects at risk of not achieving sustained results. It can take 10 years or more to see the results of health systems strengthening efforts, thus highlighting the need for longer timelines for project implementation.

Efficiency

The disbursement of project funds was generally timely, but corporate issues hampered efficiency, including the frequent turnover of Global Affairs personnel, and slow project- and planning-approval processes. The need to be nimble was seen as particularly important for projects working in highly challenging country contexts. Insufficient internal-specialist resources also negatively impacted the timeliness of program delivery and limited Global Affairs staff’s ability to engage on technical issues.

Recommendations

- For any future health and nutrition programming, consider continuing to integrate the needs of adolescents.

- To facilitate the achievement and sustainability of results, ensure that health programming promotes an integrated, multi-sectoral approach which addresses the broader determinants of health.

- Strengthen and modernize corporate reporting systems, including both software and IT systems, which support all international assistance programming, especially thematic programming like MNCH. In addition:

- Ensure that staff receive direction from senior management, along with technical support, on the systematic use of indicators, guidance tools, and compliance with reporting requirements.

- Ensure that the sequencing of corporate reporting systems is aligned to avoid retrofitting.

- For future health programming, ensure that projects have sufficient time for implementation and the greatest chance to achieve longer-term outcomes by considering project durations of up to ten years, where appropriate.

- Provide staff with sufficient and timely access to internal technical expertise, particularly health and gender specialists. Access to gender specialists would ensure that project staff have the technical support they need to best respond to policy guidance and emerging requirements including more recent expectations stemming from the Feminist International Assistance Policy.

Program background, evaluation scope and methodology

Programming Background: Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Initiative

Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH) programming encompasses key interventions along the continuum of care (including pre-pregnancy, pregnancy, childbirth, infancy and early childhood), and seeks to reduce the preventable deaths of mothers, newborns and children. For Canada, MNCH includes programming that strengthens health systems, reduces the burden of diseases, improves nutrition and ensures accountability for results.

Timeline and Resources

Canada’s commitments and the leadership role it has played have drawn sizable resources and international attention to MNCH issues. As the host of the G8 summit in 2010, Canada launched the Muskoka Initiative for MNCH, committing to spend an additional $1.1 billion over five years for maternal and child heath in low- and middle-income countries. This is on top of maintaining existing program funding of $1.75 billion over five years. This brought the total MNCH 1.0 investment to $2.85 billion (MNCH Baseline plus Muskoka).

In 2014, Canada hosted the Saving Every Women, Every Child: Within Arm's Reach Summit, where Canada renewed its commitment to MNCH programming with an additional investment of $650 million, for a total of $3.5 billion for 2015–2020. This is known as MNCH 2.0, and brought the total MNCH commitment for 2010 to 2020 to $6.35 billion.

MNCH 1.0 disbursed over $341 million above the $2.75 billion target and the MNCH 2.0 target is expected to be met in 2020.

It is expected that $208 million will be disbursed each year for three years (2017–18 to 2019–20) for sexual and reproductive health (SRH), now referred to as “Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) Baseline” funding. About three-quarters of SRHR Baseline funding is also considered under MNCH 2.0

In March 2017, shortly before the June 2017 adoption of the new Feminist International Assistance Policy, the Government of Canada announced an additional $650 million commitment over three years (2017–18 to 2019–20) for SRHR programming. SRHR funding supports the full range of sexual- and reproductive-health services and information. It includes comprehensive sexuality education, family planning, prevention and response to sexual and gender-based violence, safe and legal abortion, and post-abortion care. While MNCH and SRHR are closely connected, this new commitment is outside the scope of this evaluation

Financial Disbursements

Between 2010–11 and 2017–18, MNCH disbursements totaled $5.13 billion, with average yearly disbursements of $641 million. Disbursements are on track and the total is expected to exceed $6.5 billion by 2020.

| 2010-2011 | 2011-2012 | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $503 M | $662 M | $671 M | $634 M | $615 M |

| 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | 2017-2018 |

|---|---|---|

| $628 M | $721 M | $699 M |

| 2018-2019 | 2019-2020 |

|---|---|

| - | - |

Canada’s largest contribution to MNCH programming came from MFM, where the majority of funding provided core support to global partners with demonstrated reach and impact. Geographic branches (WGM, OGM, NGM, EGM) funded a more diverse set of actors and mechanisms, including basket funds, sectoral budget support, and contributions to NGOs and UN agencies. The majority of KFM’s funding went to projects with Canadian partners, many of which were innovative.

Overview of MNCH Disbursements by Branch (2010–2020)

Funds from 2010–11 to 2019–20 have been disbursed by eight Global Affairs Canada branches:

- Global Issues and Development Branch (MFM, 56%); $3.62 B

- Sub-SaharanAfricaBranch (WGM, 22%); $1.41 B

- Partnerships for Development Branch (KFM, 10%); $679 M

- Asia Pacific Branch (OGM, 7.6%); $494 M

- Americas Branch (NGM, 3.4%); $221 M

- International Security (IFM, 0.5%); $29 M

- Europe, Arctic, Middle East and Maghreb (EGM, 0.3%); $20 M

- Strategic Policy Branch (PFM, <0.01%); $0.46 M

The two largest branches for MNCH programming made 78% of relevant disbursements.

Programming Background

Program Design

The Muskoka Initiative (MNCH 1.0) and MNCH 2.0 share three thematic pillars:

- Strengthening Health Systems

- Prevention and Treatment of Disease

- Enhanced Nutritional Practices for mothers, newborns, and children under five

For MNCH 2.0, a fourth thematic pillar was added:

- Improving Data Generation and Use

Evaluation Scope

The evaluation covered the period of 2010–11 to 2017–18. The evaluation combined a summative evaluation of MNCH 1.0 programming from 2010–11 to 2015–16 and a formative evaluation of MNCH 2.0 programming from 2015–16 to 2017–18.

The summative evaluation component encompassed an end-of-programming approach and assessed results achieved. In contrast, the formative component focused on design and program activities of MNCH 2.0 programming. As such, some of the findings were informed to a larger extent by the summative evaluation, such as the Effectiveness and Sustainability sections, while the formative component informed the Relevance and Efficiency sections to a larger extent. When relevant, the evaluation findings and text specify if evidence was specific to a particular component.

As noted, sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) investments announced in March 2017 were outside of the scope of this evaluation. The evaluation included only sexual and reproductive health (SRH) programming that occurred within MNCH 1.0 and MNCH 2.0.

Evaluation Questions

Relevance:

- To what extent were the activities funded by MNCH initiatives (including sexual and reproductive health) aligned with recipient country needs in low and middle-income countries?

Effectiveness:

- To what extent did the activities funded under Global Affairs Canada’s MNCH initiatives achieve their immediate outcomes?

- To what extent did the activities funded under Global Affairs Canada’s MNCH initiative contribute to intended results at the intermediate outcome level?

- To what extent has programming in strengthening health systems helped to achieve greater results in other programming areas (disease, nutrition, and sexual reproductive health)?

- In which contexts were different types of partners able to achieve maximum results (e.g. Canadian partners, multilateral partners, bilateral partners, etc.)?

Gender Equality:

- To what extent has programming contributed to gender equality results and the empowerment of women and girls?

Innovation:

- Have any innovative practices, approaches, and new ways of working been integrated into Canada’s MNCH programming in recipient countries?

Sustainability:

- What is the likelihood that the results will be sustained?

Efficiency:

- Are there opportunities to improve the efficiency of programming?

Methodology

The International Assistance Evaluation Division (PRA) conducted this evaluation using a traditional mixed‑methods approach with a focus on qualitative methods.

The evaluation sample of 73 projects was drawn from a total of 987 MNCH-coded projects. The sample included projects from six branches, representing $2.2 billion of total planned international assistance disbursements over the evaluation periodFootnote 2. For the summative evaluation component, there were 56 projects, while 24 projects fell within the formative evaluation component. Seven of the projects fell under both evaluation components.

Summative Evaluation Sample: Of the 56 projects sampled, 33 (approximately half) came from the 2015 Formative MNCH Evaluation sample. The remaining 23 projects were chosen based on sampling criteria related to partner type, geographic location, country specificity, Global Affairs’ branch, funding size and funding requirements.

Formative Evaluation Sample: Of the 24 MNCH 2.0 projects selected for the formative evaluation component, two were included because of explicit funding requirements. The remaining 22 projects were chosen based on sampling criteria related to partner type, geographic location, country specificity, Global Affairs’ branch and funding size.

Graphic: Breakdown of Sample Projects by Evaluation Type; Formative = 17, Summative = 49, Both = 7. There were 73 projects in the sample, which accounted for 43% of total MNCH funding during the evaluation period

Text Equivalent

| Americas Branch | Sub-Saharan Africa Branch | Asia Pacific Branch | Partnerships for Development Branch | Global Issues & Development Branch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26 | 7 | 23 | 16 |

| Donor Partner | Foreign Government | Multilateral | Local NGO | Canadian Partner | University |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2 | 31 | 3 | 25 | 9 |

Four sample countries—Bangladesh, Mozambique, South Sudan and Tanzania—were chosen for more in-depth data collection. Evaluation missions were carried out in Bangladesh, Mozambique, and Tanzania. Due to travel constraints in-country, a desk review with phone interviews was conducted for South Sudan.

Primary and secondary data were collected through a combination of sources to provide multiple lines of evidence in support of findings and conclusions:

- Key stakeholder interviewsFootnote 3 (n=181)

- Document review

- Literature review

- Site visits (n=18)

- Financial analysis

The majority of projects included in the evaluation were concentrated within the four sample countries. The evaluation also included 15 additional projects from Afghanistan, Burundi, Ethiopia, Ghana, Haiti, Malawi, Mali, Pakistan, Senegal and Zambia, as well as 24 multi-country projects, which represented a wide diversity of MNCH programming around the world.

There are several limitations of the evaluation that should be taken into consideration when reading the report, three of which are key. Firstly, the misalignment between the project logic models and indicators and the MNCH 1.0 or 2.0 performance measurement frameworks made it difficult to assess progress toward MNCH outcomes at the corporate level. Secondly, weak data systems in some partner countries challenged the evaluation’s ability to analyze progress at the country level. Finally, staff turnover challenged the evaluation’s ability to obtain a comprehensive overview of the projects and the MNCH Initiative. To help mitigate these and other limitations, and to ensure validity of findings, triangulation was performed across methodologies, evaluators and data sources. And to compensate for staff turnover, the evaluation team spoke to multiple individuals who were responsible for MNCH projects at different periods of time. Additional details on methodology, evaluation terminology and limitations can be found in Appendix A.

Findings

Relevance

Finding 1: Global Affairs’ MNCH programming was aligned with partner government priorities and local needs in all countries sampled. It evolved to better target key gaps identified in the 2015 formative evaluation.

All projects examined were designed to address the needs and priorities of partner countries. Global Affairs’ four MNCH programming pillars: Strengthening Health Systems; Prevention and Treatment of Disease; Enhanced Nutritional Practices for mothers, newborns, and children under five; and Improving Data Generation and Use (MNCH 2.0 only), were identified by respondents as relevant areas for Canada's continued intervention. The inclusion of the Improving Data pillar in MNCH 2.0 recognized the importance of improved access to reliable information on resources and outcomes. As well, the addition of funding for Sexual and Reproductive Health in 2014 –15 helped to address a critical gap in MNCH 1.0 by placing greater emphasis on the reproductive health factors that contribute to maternal, newborn and child mortality. This was recommended by the 2015 MNCH Formative Evaluation.

In the countries examined, respondents confirmed that Canada engaged in project-design consultations with multiple levels of government and other stakeholders (including the private sector, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civil-society organizations, universities, multilateral organizations, as well as with partner donors). This enabled project designs to be tailored to local priority needs.

This tailoring was important because the 2015 MNCH Formative Evaluation had reported an imbalance of projects addressing “supply” versus “demand” issues in MNCH. Specifically, the supply side of healthcare concerned the amount and quality of care that could be made available through infrastructure and human resources (e.g. hospitals, medical equipment, beds, doctors, nurses), whereas the demand side was driven by the population’s needs or the quantity of health services the populations wants. The demand side could be influenced by various factors that facilitated or impeded access such as cultural practices and beliefs, distance to services and transportation.

There were improvements in this area since the formative evaluation. Within the evaluation project sample, there was a balance of projects addressing the supply and demand sides of MNCH issues. On the supply side, MNCH 2.0 projects aimed to address capacity building by focusing on primary healthcare infrastructure, access to essential medicines and vaccines, quality service delivery in underserved areas, and staffing and training. On the demand side, projects focused on strengthening system and service delivery integration at the primary care level, increasing community level involvement, raising awareness around available MNCH services, and addressing barriers to the access to primary care services, among others.

Finding 2: Canada’s MNCH programming was relevant to international MNCH goals. There was a continued need to address the broader determinants of health and adolescents.

Canada's MNCH 1.0 and 2.0 were designed to provide funding to support progress towards the achievement of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals. When the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were introduced in 2015, MNCH 2.0 programming remained relevant, supporting SDGs 2, 3, 5 and 6, which promote food security and improved nutrition; good health and well-being; gender equality and empowerment of women and girls; and clean water and sanitation.

External partners emphasized an ongoing need for the existing areas in MNCH which Global Affairs has been funding. At the same time, while multi-sectoral collaboration had been integrated in some of the projects within the evaluation sample, stakeholders expressed a continued need for greater focus on an integrated approach across MNCH projects that encourages multi-sectoral collaboration and also addresses the broader determinants of health. These were seen as necessary building blocks to facilitate the achievement and sustainability of planned MNCH results.

A more integrated approach would align with the United Nations’ Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescent Health 2016–2030, which advocates a multi-sectoral approach. The current version of the Strategy, launched in 2015, included adolescents as an additional target group. At the same time, adolescents were often mentioned by respondents as an area that required more focus. Adolescents were not highlighted as a specific target group in either MNCH 1.0 or 2.0, suggesting a consideration for future funding. In subsequent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights funding, adolescents were identified as a target group.

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) indicators were included in the Performance Measurement Frameworks for both MNCH 1.0 and 2.0, and some WASH projects were funded. For example, the Community Led Health project (HOPE International) in Bangladesh and the Improving MNC Survival In Warrap State project (Canadian Red Cross) in South Sudan included training in hygiene and sanitation, and construction of community tube wells and boreholes. Suggestions regarding the need for MNCH-related education covered a variety of target groups, such as health professionals, community leaders and health workers, beneficiaries, and included raising awareness of harmful cultural practices. At the same time, external partners and Global Affairs staff highlighted areas that required continued attention to help achieve improved health results. The most commonly mentioned were access to water and electricity in health facilities; health and nutrition awareness including through literacy and education; adolescent sexual health; and access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH).

Finding 3: Health systems strengthening was an essential approach for achieving sustainable MNCH outcomes. It would be a valuable overarching theme for all MNCH projects

(Graphic above depicts the Health Systems Strengthening Approach, in which the six system building blocks of 1. Service delivery 2. Health workforce 3. Information 4. Medical products, vaccines, and technology 5. Financing and 6. Leadership and governance provide access, coverage, quality and safety, and lead to the overall goals and outcomes of 1. Improved health 2. Responsiveness 3. Social and Financial Risk Protection and 4. Improved efficiency)

Text Equivalent

Health systems strengthening was a programming pillar under both MNCH 1.0 and MNCH 2.0, alongside Disease, Nutrition, and in MNCH 2.0, Data. Promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO), it is the globally accepted approach to building the capacity of health systems to deliver integrated and equitable MNCH services, and has been adopted by major donors, including the United States, the European Union, the UK, Japan, and Sweden. Consistent with academic literature, this approach was widely described by partners and Global Affairs staff as the foundation for achieving sustainable MNCH results. According to the WHO, a health systems strengthening approach seeks to improve six health system building blocks, and the interactions between them, for more equitable and sustainable health services and outcomes. Over time, the global vision of health systems strengthening has continued to evolve towards more integrated, people-centered strategies.Footnote 4

At the departmental level, Global Affairs did not track or define projects according to MNCH pillar and the evaluation could not determine the proportion of Initiative programming dedicated to health systems strengthening. The MNCH 1.0 and MNCH 2.0 Performance Measurement Frameworks described intended outcomes for the health system strengthening pillar as improving the capacity of governments and health institutions to manage health strategies and systems. There were only a few projects in the evaluation sample that exclusively focused on this, for example, strengthening the capacity of a ministry of health to plan or manage health strategies. The focus of most projects in the sample was training MNCH personnel (particularly community health workers, midwives and nurses) and providing MNCH services. This responded to an important and demonstrated need, and is one element of health systems strengthening. However, the extent to which training frontline personnel ultimately strengthens health systems is dependent on project design and implementation, as with any other type of health project.

At the same time, most of the projects in the sample contained elements of capacity building at different levels (local, regional, national) of the health system that could directly or indirectly result in health systems strengthening. Many of the projects that focused on training frontline health personnel also included elements of capacity building for health management and planning. For example, the Improving Maternal and Reproductive Health project (Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, CARE) in Tanzania included activities to improve management and accountability by local councils, including updating council health plans, and supporting local governments to better supervise health facilities. Many of the projects that focused on training MNCH personnel also renovated health facilities, provided equipment, or assisted with curriculum or policy development. Projects with a primary focus on nutrition and disease also took multiple approaches to addressing health system constraints.

Examples of multi-level capacity building:

Given the importance of health systems strengthening for all health-support programs, it would be better framed not as a programming pillar, but as an overarching theme through which all health investments are evaluated, whether they concern training of frontline health personnel, disease, nutrition, data, or other areas. While health systems strengthening was integrated to some extent in many MNCH projects, adopting health systems strengthening as an overarching theme to health programming would help to ensure that it is considered in the design of all projects seeking health outcomes.

The 2017–2020 Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) funding and the 2017 Feminist International Assistance Policy were outside the scope of this evaluation. However, there were mixed findings across lines of evidence around the continuation of health systems strengthening as a priority with the more recent focus on SRHR and the new policy. Some Global Affairs staff interviewed expressed concern that health system strengthening has not received as much attention in the new SRHR-focused programming, making it more challenging to allocate funds to health system strengthening. Further, while the Feminist International Assistance Policy doesrefer to improving equitable access, it does not clearly articulate or emphasize health system strengthening as a priority. At the same time and in support of creating stronger and more resilient health systems, as part of the larger SRHR commitment, Global Affairs has contributed $30 million between 2017–18 and 2018–19 to the Global Financing Facility (GFF). This aligns with Global Affairs’ MNCH 2.0 commitment of $200 million over five years for the creation of the GFF.

Effectiveness

Finding 4: MNCH projects in the sample have been achieving results and making a positive difference.

The majority of MNCH projects sampled made progress on achieving their intended outcomes. This was substantiated through a review of project documentation, interviews, and observations from site visits. See Appendix B for examples of results achieved by a selection of projects.

An analysis of the assessments by Global Affairs program officers of progress towards results contained in Management Summary Reports (MSRs) indicated that the majority of projects were mostly or fully meeting their outcomes. While 15% of the MSRs were not available, 82% of the reports (51 of 62) were rated 3 or higher, indicating that a project had “mostly met” its outcomes. Almost all of the 11 projects that were not on track to meet outcomes were only in their first two years of implementation. In these cases, implementation delays included: construction approvals, contracting issues, slow rollout and implementation, conflict, insecurity, and the approval processes of both Canada and the partner government.

(The graphic above shows a bar graph with the Management Summary Report (MSR) scores from 1 (not met) to 5 (exceeded). Most of the 62 sampled projects fall under “3: Mostly met”

Text Equivalent

Finding 5: There was evidence of progress towards the immediate and intermediate levels for corporate MNCH outcomes for projects in the sample.

The analysisFootnote 5 identified project results that broadly aligned with either immediate or intermediate outcomes from MNCH 1.0 or 2.0. At least 93% of projects reported the achievement of at least one result associated with either an immediate or intermediate corporate MNCH outcome. The types of results reported included:Footnote 6

- Observed decrease in number of maternal and neonatal deaths and stillbirths

- Increased access to healthcare for deliveries made in health facilities; increased numbers of deliveries assisted by skilled attendants, antenatal and postnatal visits, and access to specialized care and equipment

- Improvement in quality of healthcare staff, including management and supervisory staff as well as nurses, midwives, and doctors

- Improved national curriculum, guidelines, protocols, and policies

- More women accessing contraception and family planning services

- Greater immunization coverage and reduced stock-outs of vaccines

- Improved access to key nutritional supplements

- Improved national and local data systems

An area of focus for the evaluation was data. The evaluation found that Data Pillar projects focused on engaging and strengthening government data-system capacities and usage. While these projects were in early stages and fell within the formative evaluation component, initial results showed that the data projects were making progress in strengthening data and civil registration and vital statistics systems (see Appendix B for examples).

Finding 6: While it is difficult to attribute success solely to Canadian international assistance, MNCH projects contributed to the decreases in child mortality in Bangladesh, Mozambique, Tanzania and South Sudan. Little evidence beyond estimates was available to report on maternal mortality rates in these countries.

The MNCH Initiative’s ultimate outcome envisioned “increased survival of mothers, newborns and children under five in Muskoka-funded countries.” This was aligned with development effectiveness principles and the 4th and 5th Millennium Development Goals on maternal and child health in low and middle-income countries.

Under-five and neonatal mortality rate estimates (per thousand live births) ; For Bangladesh, Mozambique, South Sudan and Tanzania, the Under 5 Mortality rate and Neonatal mortality rates slope down from 2010 to 2017.

Text equivalent

Graphic; Under-five and neonatal mortality rate estimates (per thousand live births) ; For Bangladesh, Mozambique, South Sudan and Tanzania, the Under 5 Mortality rate and Neonatal mortality rates slope down from 2010 to 2017.]

Canada’s MNCH programming in the four sample countries contributed to decreased national rates of under-five child mortality. According to World Health Organization (WHO) data reports, the under-five mortality rates in all four countries decreased gradually between 2010 and 2017, which was the latest year for which data was available. Neonatal mortality rates showed a much slower decrease over this period.

For maternal mortality, there was insufficient information to reach a firm conclusion. WHO data on maternal mortality was limited to two years: 2000 and 2015. These estimates showed a decrease in maternal mortality ratios over the 15-year time span for all four countries. However, the WHO database indicated limitations in the ability to accurately measure the maternal mortality ratio. These limitations are due to the weak vital-registration and health information systems in most developing countries.

Finding 7: The Department could not fully report on the overall results of the MNCH initiative as a key thematic priority across the Department, primarily because of a misalignment of performance indicators between the project and the departmental level.

The Departmental MNCH Indicators and Performance Management Framework (PMF) were finalized very late in the funding cycle, after MNCH programming was well underway and departmental units had developed their own project level indicators. This negatively affected Global Affairs’ ability to roll up and report on results at the departmental level for this flagship initiative. At the same time, the concurrent development of the new Departmental Results Framework (DRF) also made the inclusion of MNCH results in this higher-level performance measurement process difficult.

| 2014 | $3.5 billion MNCH 2.0 commitment announced. |

| 2015 | MNCH 2.0 funding commenced, immediate disbursements encouraged. In the meantime, in 2015, Partnerships and Development Branch (KFM) needed to roll out a call for proposals on its $450 million MNCH investment. In the absence of departmental indicators, KFM developed 18 common indicators, aligned with World Health Organization indicators, for partners to monitor performance. However, methodological notes were never developed, as work on indicators was progressing at the corporate level. |

| 2016 | Draft PMF shared and teams instructed to use it in the interim. |

| 2017 | After a consultative process, and in response to the 2016 Audit of MNCH Commitments, the Performance Management Framework with 43 departmental indicators was finalized and submitted to the Treasury Board Secretariat three years after the funding announcement. As well, since many different needs were accommodated across the Department, these indicators were no longer harmonized and thus no longer met international best practices. |

| 2018 | Methodology notes on the departmental indicators were developed for partners. |

| 2020 | MNCH 2.0 funding ends. |

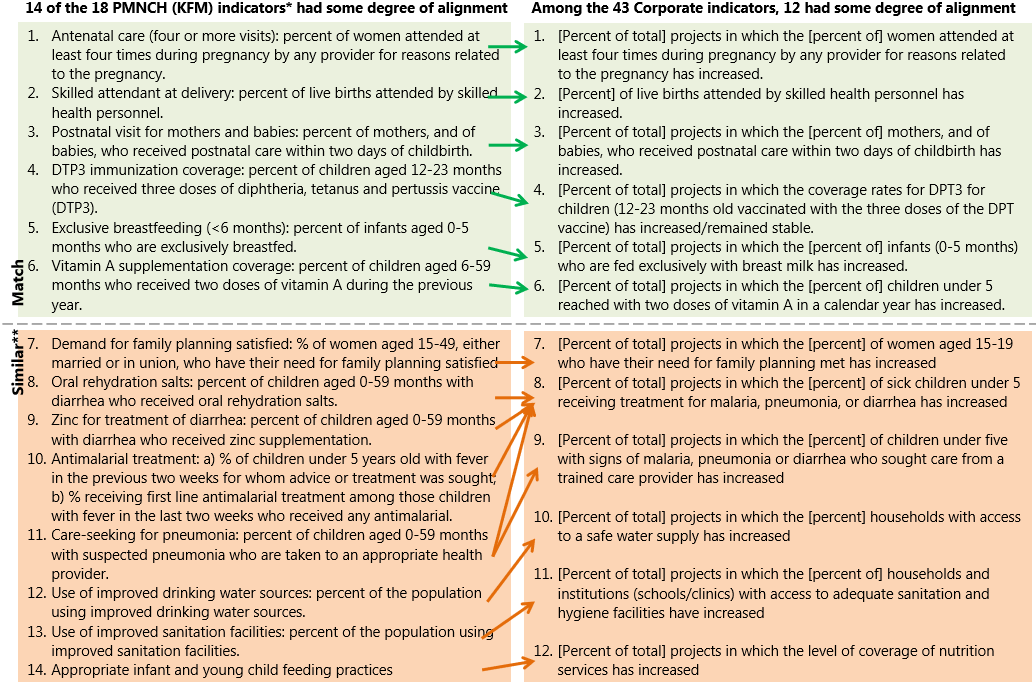

Comparing MNCH 2.0 Departmental and KFM Indicators

Of the 43 departmental indicators and the 18 KFM indicators:

- 6 indicators were well matched.

- 8 indicators were similar in nature.

- The remaining indicators did not match.

A more detailed comparison of indicators can be found in Appendix E.

Finding 8: Reporting challenges for effectiveness across the department were compounded byinadequate reporting software that was not fit for purpose, a lack of adequate technical support for staff, weak country-level data systems, and a lack of attention to data projects designed to help Global Affairs report at the impact level.

Reporting Software Issues

Until 2018, one of the tools that Global Affairs’ project officers were using to report on project-level results was the Monitoring and Reporting Tool (MRT), within the Systems Applications and Products in Data Processing (SAP) software that was used for project planning. This system allowed the input of only narrative text; numbers and aggregate results could not be entered. MNCH performance indicators were not entered in a menu format in the SAP system, so project officers had to search offline for the appropriate MNCH indicators when entering data into the reporting system. These design issues led to low compliance rates among officers for planning and reporting on MNCH projects when using the MRT.

At the time of the evaluation, not enough resources had been committed to improving and modernizing software, IT systems, and providing guidance on their use. In 2018, the Results-based Management Centre for Excellence piloted a new version of the reporting system using Excel spreadsheets (the MSR+). At the time of the evaluation, major work still needed to be done to modernize the reporting system. This would include creating a user-friendly, intuitive interface, connected to a well-designed performance management framework, such that real-time information and a reporting roll-up would be accessible to all users in the Department.

Technical Support

Technical expertise to support departmental reporting systems (such as the MRT and MSR+) was disjointed and insufficient. Results-based management specialists gave advice when indicators were being designed, but their advice was not always reflected in the end product, and they did not have health sector expertise. Health specialists gave input on the health content, but did not necessarily understand results-based management. Finally, corporate reporting teams had to reconcile project reporting, but they had neither results-based management nor content expertise.

Weak Country-Level Data Systems for Outcome Data

If Global Affairs were able to effectively aggregate its project level results (immediate and intermediate outcome data), the next logical step would be to report on results achieved at the country level and then the departmental level. However, many national data collection systems continued to be weak and unreliable. Cognizant of this, Global Affairs has made efforts to strengthen local and national data systems, as reflected by the addition of Pillar 4: Improving Data Generation and Use for MNCH 2.0.

Data Projects Designed to Help Global Affairs Improve Reporting at the Impact Level

As part of Pillar 4 programming, Global Affairs engaged Johns Hopkins University through a few projects to help improve reporting at the impact level (country level). This was after the 2015 MNCH Formative Evaluation found that it was difficult to attribute higher-level outcomes for MNCH to Canadian funding. These projects included multi-country projects to work with partner governments to develop national evaluation platforms; to strengthen data collection tools and approaches for all types of partners; and to pilot real-time results-tracking methodology. Johns Hopkins University projects have continued to do important work in strengthening data generation and increasing capacity to analyze and report on MNCH results at the country level.

However, at the time of the evaluation, Global Affairs had not yet utilized these projects to strengthen its reporting ability. Challenges included: funding approval timelines that did not logically coincide with the Canadian partner funding that Johns Hopkins University was supposed to influence; and the turnover of several officers responsible for the Johns Hopkins University files in the Health and Nutrition Bureau (MND).

Finding 9: At the same time, project timeframes were frequently insufficient for implementation and achieving long-term results.

A recurring issue of concern throughout the evaluation was project timeframes. All of the partners and staff who commented on this issue noted that three-to-four year project timeframes were insufficient to meet outcomes. Some partners also found five years to be inadequate, especially given that implementation was frequently shortened by delays in various approval processes and that no-cost extensions were frequently required. Some projects faced additional internal start-up issues, such as obtaining ethical approval for research, building relationships with new partners, and waiting for in-country procurement or approval processes. In areas where Canada has been working to achieve long-term results, such as health systems strengthening, longer timelines were even more important. Often, the projects that were perceived to be most successful were building on a previous phase, also suggesting that longer-term projects are more likely to achieve meaningful results.

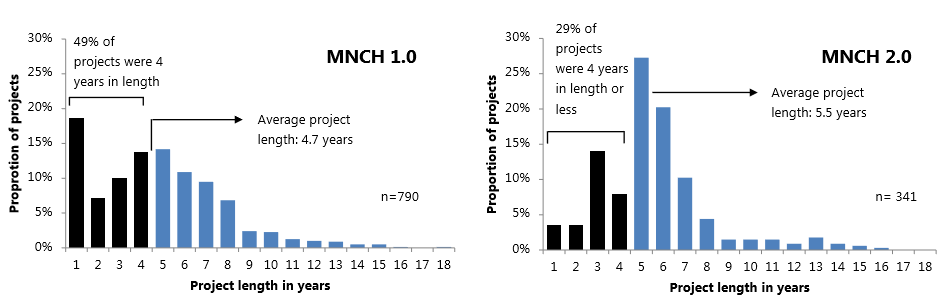

According to data from CFO-Stats*, the average length of MNCH projects overall was 4.7 years (the median was 5.0 years). Overall, 36% of project timelines were three years or less and 49% were four years or less. This improved from MNCH 1.0 to MNCH 2.0, as the number of project timelines of three years or less decreased to 21%, and those of four years or less decreased to 29%.

The graphic shows that the average project length for MNCH 1.0 was 4.7 years, and that 49% of projects were 4 years or less in length; for MNCH 2.0, the average project length was 5.5 years, and 29% of projects were 4 years or less in length

Text Equivalent

*Analysis verified by CFO-Stats on December 28, 2018.

Finding 10: Canada was seen as a respected donor with a positive track record in contributing to national-level policy dialogue and donor coordination in the health sector in all countries sampled.

Over the evaluation period, Canada actively participated in and chaired various health sector partner groups in all four sample countries. Canada maintained good working relationships with donor partners, as well as with health ministries. This type of engagement facilitated the effectiveness of programming in achieving results.

Donor partners (as well as national and subnational partner-government representatives) recognized Global Affairs staff for their positive efforts and participation in policy dialogue in all countries sampled. Canada enjoyed a strong reputation as an active and effective player in providing sector support through policy dialogue. This strong reputation was demonstrated by Canada often occupying the role of Chair at the donor table. Some internal and external interviewees also noted that Canada stood out for its role in influencing and supporting the adoption of gender strategies in health sectors in the four sample countries.

For a number of projects within the sample, Global Affairs staff participated in health sector planning and coordination efforts with donor and implementing partners, as well as partner governments.

Nonetheless, in all four countries sampled, the overall level of coordination among donors varied during the evaluation period. It tended to fluctuate depending on the type of funding mechanism used, the level of partner government involvement, motivation of the individuals involved, staff turnover within Global Affairs and partner organizations, shifts in donor policies, changes in local governance, and changing or unstable political contexts.

At the same time, the evaluation found a few instances of project overlap and duplication among donors. For example, multiple donors came forward independently to support MNCH projects in two regions identified by the Government of Tanzania as underserved (Simiyu and Shinyanga). Subsequently, 14 implementing partners worked separately in the regions with inadequate coordination. In particular, donors-including Canada-duplicated efforts by offering similar training to the same health workers.

Finding 11: Given that the best-fit choice of partner modalities is context-specific, overall, Canada had an appropriate mix of partner modalities in its MNCH programming. This provided a robust approach to achieving planned results.

The evaluation found that engaging with a diversity of partner modalities provided Canada with a robust approach to delivering on its MNCH priorities and achieving planned results.

Primary considerations for partner selection included the project context, as well as the partner’s geographic experience, relationships and networks on the ground, subject-matter expertise, and capacity.

The analysis did not find a single type of partner that would be able to achieve maximum results in all contexts. Interviewees highlighted that partner selection was context-specific and that partners’ strengths and weaknesses varied by context. An additional analysis of documents and Management Summary Reports (MSRs) was conducted in an attempt to further inform the context in which different types of partners achieve maximum results. The document review analysis indicated that overall, projects by all types of partners achieved notable results, although results varied in scope and scale. Many projects in the evaluation sample were implemented using multiple types of partners, thus adding to the complexity of the analysis and the difficulty to attribute results achieved to a single type of partner. Rather, this diversity may have facilitated success by engaging the strengths of different types of partners.

Similarly, the analysis of ratings from MSRs revealed no notable differences by partner type in terms of whether projects were on track to achieve expected intermediate outcomes. These positive findings across types of partners were not a surprise, since the majority of partners in the sample were longer-term trusted partners, for which Global Affairs carries out regular due diligence processes.

See Appendix D for additional analysis on the strengths and weaknesses of each type of partner.

Gender Equality

Finding 12: Canada was recognized as a leader in advancing gender equality.

This evaluation assessed the integration of gender equality as a cross-cutting priority (2010–11 to 2016–17), and more recently under the Feminist International Assistance Policy (from June 2017 to the end of fiscal year 2017–18).

During these periods, Canada’s advocacy efforts in advancing gender equality in MNCH influenced positive changes in partner countries. At the highest level, all four sample countries integrated gender equality into national policies and strategies. Many implementing partners actively promoted gender equality at both the policy and programming levels. Many of these implementing partners attributed their active promotion of gender equality to Canada’s leadership.

Finding 13: Overall, there was an increased effort to ensure project activities and delivery approaches were gender sensitive.

Projects implemented under the MNCH Initiative reflected a multi-faceted approach to addressing gender equality issues. These ranged from supply-side oriented interventions to ones that targeted social and cultural norms that impeded demand for health services.

Examples of different types of interventions within the evaluation sample included:

- Implementing tools and guidelines to improve gender balance among service providers;

- Capacity building activities to increase gender sensitivity in service delivery;

- Engaging men and women in community dialogue to raise awareness of gender equality issues; and

- Undertaking communication and education campaigns to transform gender norms through attitude and behavior changes.

Global Affairs staff and some partners indicated that gender equality had become a stronger and more ingrained element of programming than it was prior to the introduction of the Feminist International Assistance Policy (June 2017).

Finding 14: Observed progress towards results, and progress reported by stakeholders, suggested positive changes towards increasing gender equality.

An analysis of project-approval documents reflected that almost half of the projects in the evaluation sample achieved a gender equality code of 2. This code indicates that gender equality has been integrated into project design. Among projects sampled, the extent of gender equality integration at the project level varied, as some projects targeted basic gender balance, while others addressed root causes of inequality, such as gender norms, community traditions, or power relations in the family.

Gender Equality Codes for Sampled Projects; A graph showing the percentage of 75 sampled projects given a certain gender equality code; None (0) = 21%, Limited (1) = 31%, Integrated (2) = 48%, and Specific (3) = 0%]

Text Equivalent

* Although the evaluation sample contains 73 projects, one project (Grand Challenges Canada) was treated as a consolidation of three project iterations reflecting 75 gender codes. In this analysis, each project’s gender equality code was counted.

In the sample, there were examples of observed and reported gender equality results including:

- Improved female participation in the workplace;

- Increased capacity among frontline service providers in providing gender sensitive care;

- Increased male involvement in domestic activities and in accessing healthcare services;

- Increased mobility, social status, and participation in decision-making for women; and

- Increased access to maternal health services for women.

Examples of observed increased empowerment of women and girls

- SHOW project (Bangladesh): beneficiaries of the “Freedom” women’s group said that through participating in the group’s activities, they gained more knowledge, income, independence, and respect from their husbands. As a result, they were more likely to give birth at health centers rather than at home.

- Community-Led Health project (Bangladesh): informants mentioned that women were more involved in decision-making at the household level.

- Accelerating Efforts to Improve MNCH project (Tanzania): informants reported improvements in women’s decision-making about access to healthcare.

Innovation

Finding 15: Global Affairs has successfully supported some partners in engaging in innovative work, including mechanisms such as Grand Challenges Canada.

Within the evaluation sample, there was evidence that innovations in MNCH programming have achieved results and improved the efficiency of resultswhen trusted partners had been given the flexibility and resources to be innovative. A prominent example of this was the Grand Challenges Canada funding model. Through Canada’s support, this mechanism was able to quickly run calls for proposals and fund innovative projects. This was done while acknowledging that a high percentage of ideas would not be successful because of their experimental nature. Successful ideas were able to obtain subsequent stages of funding and would later be linked to other partners who would be able to bring these innovations to scale.

Examples of successful Grand Challenges Canada innovations included:

- The Friendship Bench (University of Zimbabwe): Thousands of patients suffering from depression received help from a network of grandmothers trained in talk therapy. Once trained, these grandmothers met patients on "Friendship Benches" outside health clinics.

- Chlorhexidine (John Snow International): In Nepal, the risk of newborn death decreased by 23% through the use of chlorhexidine on newborns’ umbilical-cord stumps.

- Affordable, eco-friendly menstrual health products in rural Rwanda (Sustainable Health Ventures): This patented method converted locally available banana fibres into the absorbent core of disposable menstrual pads without the use of chemicals. The pads were sold to women and to schools to be used by girls.

At the same time, there was room for improvement. Specifically, Grand Challenges Canada has faced some challenges in coordinating with wider government efforts and strengthening its monitoring capacity.

Other examples of successful MNCH innovations from the evaluation sample fell into two broad categories: technological innovation; and innovative approaches and practices to encourage behaviour change (See Appendix C).

Finding 16: While Global Affairs has made efforts to promote innovation, staff expressed concerns that the Department did not yet have a culture that fully fostered innovation in employees’ daily work.

Global Affairs has been successful at supporting partners in engaging in innovative work. The Department also developed a definition for innovation and created an Innovation Lab. Senior management’s communications supporting innovation have been visible and numerous. At the time of the evaluation, however, staff expressed concern that the Department had been less successful at promoting innovation internally. Specifically, many respondents noted that Global Affairs Canada remained risk adverse, which was less conducive to innovation. While many members of Global Affairs staff interviewed at headquarters and in the field were open to innovation, many expressed confusion about the concept of innovation. These staff noted that have only received messaging that they should be “doing” innovation, with little additional support.

Some interviewees suggested that relevant specialists (in health, gender equality, etc.) might be better placed to advise on relevant innovative practices. At the same time, staff reported that heavy demands to support programming across the Department meant that the relatively small number of specialists did not have sufficient time to stay abreast of relevant practices in their area of work.

Global Affairs staff and external stakeholders reported “innovative” practices at the project level that were closer to examples of established best practices. Sometimes these practices were taken from development work in another area and applied in that country or context. Examples of this include using participatory or community-centred approaches or different forms of media to disseminate project messaging.

Identified barriers to innovation expressed in interviews included:

Some respondents also emphasized that although innovation should be considered for problems without effective solutions, it was also important to focus on proven interventions that effectively meet beneficiaries’ basic MNCH needs. Examples included vaccine campaigns with wide coverage across a population and ensuring basic training standards were achieved for community health care workers.

Sustainability

Finding 17: Although no mechanism existed to assess the sustainability of MNCH projects after funding ended, evidence suggested that the effects of some MNCH interventions would likely endure beyond the duration of the project.

At the time of the evaluation, Global Affairs did not have a reporting mechanism that required program officers to follow-up on monitoring the sustainment of results achieved beyond the lifecycle of project funding. However, evidence collected from interviews and site visits in all four sample countries indicated that the achievements made by some MNCH projects were likely to be sustained, for example:

- Sensitization and awareness activities conducted by community groups were continuing to influence positive behavior changes within communities.

- Trained community health workers and volunteers were continuing to provide basic health services without incentive payments.

- Relevant policies, guidelines, and processes were being developed and implemented to support the scale-up of interventions.

- Economic production activities were being operated on a cost-recovery basis to generate revenues after financial support ends.

How Japan Assesses Sustainability The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) uses a more comprehensive assessment of sustainability over time. Based on an assessment of risk at project closeout, JICA conducts “ex-post evaluations” up to three years after the completion of the project. These evaluations are carried out with the view that it can take several years for the results of some projects to take root and for technical, financial and social problems related to sustainability to emerge. During ex-post evaluations, JICA examines project effectiveness, impact, and sustainability at that point in time. If concerns exist, JICA may also conduct a second round of ex-post evaluation seven years after project completion. This involves verifying the project’s effectiveness, impact and sustainability, as well as the extent to which recommendations drawn from the evaluation were being applied. Ex-post evaluations also aim to generate recommendations and lessons learned. JICA’s portfolio includes health projects.

Finding 18: Key strategies for sustainability included promoting ownership, increasing participation of stakeholders at all levels, and integrating cross-sectoral considerations.

Some MNCH projects within the evaluation sample adopted strategies to achieve sustained systemic impacts through promoting government ownership and stewardship, such as:

- Aligning interventions with the recipient country’s national plans and priorities;

- Advocating for increased government commitment and financial accountability;

- Pursuing activities that support the mobilization of additional domestic resources;

- Supporting the country government to enhance the capacity of its national system

to scale up health services for mothers and children.

Other projects relied on a community-based approach focused on knowledge transfer and behavior change to achieve long-term social and cultural sustainability. Examples included:

- Undertaking community sensitization activities to raise awareness and influence behaviour change among peer groups;

- Integrating sustainable agriculture practices and other business approaches to enhance economic self-sufficiency; and

- Empowering and mobilizing community actions to strengthen accountability of local government.

Several lines of evidence highlighted the need for some projects to place more effort on engaging other sectors, such as infrastructure, agriculture, and education, to develop greater potential for effective and sustainable interventions. It was noted that several projects had proactively integrated cross-sectoral considerations. However, a few projects lacked attention to cross-sectoral issues and consequently faced the risk of a reduced likelihood of sustainable results. For instance, a hospital was constructed without access to water or electricity.

Finding 19: Several internal and external factors challenged the achievement of sustainable MNCH results, thus creating a need for ongoing donor support.

In all four sample countries, partner governments offered limited national commitment and capacity to fully finance public healthcare. As a result, funding for MNCH initiatives continued to rely heavily on international assistance.

Although many projects in the evaluation sample focused on health system strengthening and capacity building at all levels, concerns were raised in 23 projects in which activities exceeded the partner country’s technical and human capacities. In addition, these projects had not been designed to ensure appropriate transfer of resources, skills and knowledge at the end of the project’s intervention. For instance, due to a lack of resources and management capacity in some recipient-country governments, the continued operation of donor-supported activities faced challenges at the end of project periods. These challenges included retention of health workers, procurement and distribution of medicines, operation of ambulances, maintenance of training programs, and provision of routine vaccination services.

Moreover, many MNCH projects had a limited window for project implementation, which decreased the likelihood of sustainability. For instance, the Health Pooled Fund, implemented by the United Kingdom’s Department of International Development in South Sudan, was designed to directly respond to the government’s capacity challenges. The Fund was set up to support service delivery over five years. Donors recognized that an even longer term—of eight to 10 years—might be necessary to fully achieve government ownership. For the time being, the Fund was designed to align with the South Sudanese Ministry of Health’s five-year Health Strategic Plan.

Efficiency

Finding 20: Slow project and planning approval processes during the evaluation period caused significant delays in project implementation. This limited Global Affairs’ ability to be responsive. At the same time, project partners appreciated Global Affairs’ efforts to be flexible with extensions.

Many partners found Global Affairs’ approval processes to be slower than those of other donors. Global Affairs staff echoed these concerns. This finding was consistent with the recent Honduras (2017), South Sudan (2017) and Vietnam (2018) evaluations.

Although the Department records project approval dates, it does not systematically nor consistently track approval process start dates. Interview findings suggested that various aspects of the process before and after project approval caused significant delays. Some respondents reported waiting months to receive approval on Gender Equality Assessments, environmental assessment processes, and Project Implementation Plans, which resulted in a year of delay. As a result, projects lost time for implementation, and no-cost extensionsFootnote 8 were frequently required.

Some partners interviewed noted their appreciation for Global Affairs’ flexibility in granting these extensions, despite lengthy delays in some cases. For example, it took eight months to approve a no-cost extension for the Making Motherhood Safe project in Tanzania.

When there were long gaps between when a partner was ready to implement their project and a project was approved, there could be real impacts. According to external partners, impacts of these delayed processes were far-reaching. Global Affairs staff agreed. Specifically, it hampered decision-making and inhibited Global Affairs’ ability to be flexible and responsive. It also affected project budgets and in some cases resulted in delays in providing planned health services. Participation in working groups and partnerships was negatively affected by slow inputs and comments.

Some Global Affairs staff described a loss of credibility as well as lost opportunities. On some occasions, slow processes hindered Canada’s ability to take a leadership role or respond in a timely manner to requests from partner governments.

For example, at the request of the Government of Tanzania, Canada planned a project site in an underserved region in Tanzania. However, since Canada did not approve the funding in a timely manner, the site was transferred to a multilateral organization to implement the initiative.

Some respondents also reported that Global Affairs’ contracting mechanisms were very slow and inflexible, and thus staff hesitated to use them. This meant, in some cases, that staff could not take initiative to play a leadership role when working with other donors, such as offering to pay for a consulting contract to support an emerging need for technical assistance.

A lack of flexibility because of slow processes was particularly problematic in fragile and conflict-affected states, where the context could be dynamic and unpredictable. While some MNCH project partners praised the responsiveness of Global Affairs during the crises in South Sudan, most Global Affairs staff reported that systems and processes were not fast-moving or flexible enough to shift programming in response to a crisis. This was consistent with findings from the South Sudan evaluation (2017).

Finding 21: Financial disbursements to MNCH projects were generally timely. However, late disbursements for some health pooled funds disrupted delivery of planned services.

Implementing partners for projects in the sample indicated that funds were generally disbursed promptly. However, in the case of Canada’s contribution to national health pooled funds in Tanzania and Mozambique, funds were frequently late. In Tanzania, this was due to the need to disburse money “out of cycle”, which required a significant volume of documentation to justify release of payment and resulted in large delays.

These delays meant that local health officials and facilities did not have the planned resources to provide health services when expected. In Mozambique, a national government crisis and concerns around overall use of national funds led Canada, along with other donors, to suspend a portion of its funding and delay disbursements to the health sector Sector Wide Approach (SWAp) in 2016. As a result, the Government of Mozambique did not have the resources needed to provide health services. To minimize this risk in the future, Canada’s funding to Mozambique’s health-sector budget will be facilitated by the Global Financing Facility using performance-based financing. This does not, however, eliminate the risk that the flow of funds could be interrupted, highlighting Mozambique’s dependence on donors.

Finding 22: Insufficient internal specialist resources negatively impacted timeliness of program delivery, as well as Global Affairs’ ability to engage in technical and strategic discussions.

Many staff working on MNCH projects had experience with health projects or engaged local in-country staff with health expertise. However, many Global Affairs staff in the geographic branches reported that they have not had adequate access to health expertise to support internal programming needs. During the evaluation period health, gender, environment, and construction specialists’ time was in very high demand. According to interviewees, this meant that their input was often received late, which resulted in project delays. According to interviewees, the lack of availability of the few health specialists also limited Global Affairs’ ability to meaningfully engage in relevant technical and strategic discussions with other donors and multilaterals. A similar finding was noted in the Synthesis of Evaluations of Grants and Contributions Programming funded by the International Assistance Envelope (2017).

Finding 23: Frequent turnover of Global Affairs personnel made the management of MNCH projects less efficient and presented a potential reputational risk.

In general, moving staff to new positions every few years brings the benefit of the expansion of knowledge of different aspects of an organization and provides for a dynamic career. At the same time, Global Affairs staff at various levels expressed concern and frustration with the institutional and individual challenges associated with one to three-year postings for overseas rotations and mobility at headquarters.

For overseas rotations, many respondents noted that three years was an inadequate timeframe to build language skills and a good understanding of the local context. Some reported that short rotations hampered diplomatic efforts to build strong relations by weakening relationships with government representatives. It was also noted that short rotations weakened the ability to contribute to technical discussions, and could lead to ill-informed decision-making. This was exacerbated by the absenceof overlap and transition time between staff. Turnover was especially frequent wherever working conditions were difficult, such as in conflict-affected states.

For mobility, many respondents mentioned that turnover in positions at headquarters also resulted in a loss of institutional memory and more inconsistent management of individual projects and larger initiatives. For example, respondents reported that high rates of turnover and vacancies within the Health and Nutrition Bureau (MND), the corporate unit responsible for MNCH since 2015, had made it particularly challenging for staff to maintain institutional knowledge, meet deadlines, and respond to requests.

Frequent turnover also resulted in less effective relationships with implementing partners. Some partners reported that Global Affairs project officers changed more than once a year. This was challenging, time-consuming and confusing for these partners, who had to repeatedly orient new officers to their projects.

Finding 24: Over the course of the evaluation period, there were several instances of a need for better communication and guidance on new policies and priorities.

The 2017 funding commitment for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) was a new allocation of money to empower women and girls and to contribute to gender equality. At the time of data collection during the summer of 2018, there was widespread confusion among program and project staff interviewed about how SRHR would fit into MNCH, or whether it had replaced MNCH. This suggests that there had not been enough clear messaging internally or externally around this new focus.

In addition, while staff received high-level instruction to implement the new Feminist International Assistance Policy, many Global Affairs staff interviewed noted that at the time there had not been enough guidance on how the Feminist International Assistance Policy could be adapted or embraced in programming, including MNCH. This finding is consistent with the recent Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Co-operation Peer Review of Canada (2018).

Finding 25: Retroactively applying changes in reporting requirements put an unnecessary burden on implementing partners.

In 2015, new mandatory project-reporting processes and ways of working were applied to existing projects. This was seen by some partners as disruptive to the efficiency of ongoing programming. For example, implementation of a large training project in Mozambique was disrupted after the project had to accommodate new reporting and results-based management requirements.

Context-specific challenges in MNCH programming in fragile and conflict-affected states MNCH projects have encountered major in-country challenges including political instability, economic downturns, natural disasters, health sector strikes, humanitarian crises, armed attacks, extreme inflation, and mass population displacement. As is normal for operations in fragile contexts, these types of challenges resulted in: significantly increased security costs; limited ability to travel in-country; and sometimes rapid changes in implementation plans. Examples of countries subject to these challenges during the evaluation period include Mozambique, Bangladesh (Rohingya crisis), and Haiti. Many of the projects in South Sudan were seriously disrupted due to widespread conflict in 2013 and 2016. Even where the context may be stable, efficiency was challenged when working within country systems with limited capacity and human resources. Unstable country contexts highlighted the need for the Department to be more responsive and adaptable to changing conditions, particularly through more flexible and timely approval processes. Some respondents noted that if Canada wants to effectively support programming in fragile and conflict-affected states, where need is often the greatest, the inherent risks must be better accepted and accommodated.

Recommendations and considerations for future programming

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: For any future health and nutrition programming, consider continuing to integrate the needs of adolescents.

Recommendation 2: To facilitate the achievement and sustainability of results, ensure that health programming promotes an integrated, multi-sectoral approach which addresses the broader determinants of health.

Recommendation 3: Strengthen and modernize corporate reporting systems, including both software and IT systems, which support all international assistance programming, especially thematic programming like MNCH. In addition:

- Ensure that staff receive direction from senior management and technical support on the systematic use of indicators, guidance tools, and compliance with reporting requirements.

- Ensure that the sequencing of corporate reporting systems is aligned to avoid the retrofitting.

Recommendation 4: For future health programming, ensure that projects have sufficient time for implementation and the greatest chance to achieve longer-term outcomes by considering project durations of up to ten years, where appropriate.

Recommendation 5: Provide staff with sufficient and timely access to internal technical expertise, particularly health and gender specialists. Access to gender specialists would ensure that project staff have the technical support they need to best respond to policy guidance and emerging requirements, including more recent expectations stemming from the Feminist International Assistance Policy.

Considerations for Future Programming

Policy Considerations

Health systems strengthening overarching theme: Given the widespread acceptance of health systems strengthening as a foundation for sustainable results, programs could consider adopting health systems strengthening as an overarching theme when proposing health investments. This would include the training of frontline health personnel, disease, nutrition, data, and other aspects of health programming. This would also help to ensure that health systems strengthening is considered in the design of all projects seeking to deliver health outcomes.

Communicate guidance on shifts in departmental priorities and policies in a timely manner: Knowing that there will always be changes inpriority commitments as contexts change, Global Affairs could embrace a more fulsome approach to change management. Specifically, the Department could review and develop streamlined processes to ensure that when commitments shift, the necessary guidance and support will be available to staff as soon as possible. These processes would increase the timeliness of implementing new departmental priorities and policies, such as Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights programming and the Feminist International Assistance Policy.

Programming Considerations

Timeliness of project and planning approval: In line with efficiency recommendations from recent evaluations such as South Sudan (2017) and Honduras (2017), as well as the Audit of the Harmonization of the Administration of Grant and Contribution Programs (2017), MNCH programming branches could work towards streamlining internal processes to reduce the time required to complete project agreements, as well as further standardize requirements.

Building learning for sustainability into projects: Sustainability is concerned with ensuring the benefits of an intervention are likely to continue after donor funding has ended. To support the sustainment of results, programs can better incorporate sustainability considerations into the planning and design phase of projects to ensure the appropriate transition of resources, skills and knowledge at the end of the intervention. For high-risk or innovative projects, programs could also experiment with new approaches to monitor whether results are actually sustained after funding has ended.

Reporting requirements: To minimize disruption and burden on partners, Global Affairs could consider the value of applying any newly developed reporting tool or process only to future projects rather than existing projects.

Initiative mapping: To inform program design, facilitate coordination and avoid duplication, global initiatives (like MNCH), could map current and planned initiatives, along with funding from all donors, in recipient countries. This could be done at the country level. For example, KFM has been working with CanWach on Project Explorer, which includes mapping of 134 MNCH projects funded by Global Affairs.

Management Considerations

Managing staff mobility and rotation: International assistance branches could identify best practices and develop procedures to ensure robust knowledge transfer to incoming staff.

Comprehensive Results Framework: Given that priority commitments change, a streamlined process could be established to develop and roll-out coherent Department-wide results framework (including program logic model, performance measurement framework with international best-practice aligned indicators, and methodology notes for partners). This should be done in a timely manner when new commitments are announced. The results framework should be in place as early as possible to inform the program plans that respond to priority commitments.

Appendix A: Evaluation Terminology and Limitations

Evaluation Terminology

Throughout the report, the terms “some,” “many” and “most” are used to denote percentages of qualified respondents on a topic: 25% to 49%; 50% to 74%; and 75% to 99.9%, respectively. “Qualified respondents” refers to interviewees who could knowledgeably speak to a given topic.

For example, pertaining to knowledge of Global Affairs’ bilateral MNCH programming in a specific country, interviewees with knowledge of that programming might include the officers responsible for that country (e.g. n=3); the deputy directors responsible for that country (n=2); the head of mission for that country (n=1); a Global Affairs health specialist (n=1); the implementing partners (n=5); beneficiaries (n=5); and a donor partner (n=1). Thus the total number of qualified respondents for the evaluation on this topic would be 18 (n=18).

In this context, “bilateral” programming is an internal Global Affairs term for programming disbursed by a country program within a geographically themed branch e.g. Sub-Saharan Africa Branch (WGM), rather than programming that is disbursed by the Global Issues and Development Branch (MFM) or by the Partnerships for Development Innovation Branch (KFM).

| Number | Description | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Project logic models and indicators did not usually align with the MNCH 1.0 or 2.0 performance measurement frameworks. This posed a challenge for the analysis of progress towards MNCH outcomes at the corporate level. | While the evaluation was unable to aggregate results of the Initiative, it identified examples of results achieved at the project and corporate level, as well as areas of challenges and successes. |

| Access to documents by project varied. In some cases, key documents could not be located due to gaps in information management and staff turnover. Despite large amounts of funding set aside for decentralized evaluations, few were commissioned. | The evaluation relied on the documents that could be located, and triangulated the information with data from interviews and site visits. Out of 73 projects, 23 project-level evaluations were available to the evaluation team. |