Evaluation of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada

Evaluation Report

Prepared by the Evaluation Division Global Affairs Canada

December 2021

Table of contents

- Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Executive Summary

- Evaluation Scope and Methodology

- Program Background

- Findings

- Conclusions

- Considerations and Recommendations

- Annexes

Acronyms and abbreviations

- ABAC

- APEC Business Advisory Council

- ABLAC

- Asian Business Leaders Advisory Council

- Act

- Asia-Pacific Foundation of Canada Act

- APEC

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

- APF Canada

- Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada

- CEO

- Chief Executive Officer

- CGA

- Conditional Grant Agreement

- CIGI

- Centre for International Governance Innovation

- CPI

- Consumer Price Index

- FOIP

- Free and Open Indo-Pacific

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GIC

- Governor in Council

- HR

- Human Resources

- ISED

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- PECC

- Pacific Economic Cooperation Council

- PGRF

- Post-Graduate Research Fellows

- OGDs

- Other Government Departments

Executive summary

This evaluation examined the operations and activities of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada during the period from 2014-15 to 2019-20. The objective was to assess the alignment of the Foundation's activities with the requirements of the Conditional Grant Agreement (CGA), along with the effectiveness of the Foundation's governance structure, progress toward outcomes, and the state of communication with Global Affairs Canada (GAC). This report presents the evaluation findings, conclusions and considerations as well as recommendations.

Starting in 2014, the Foundation's business model evolved toward a more action-oriented approach serving broader audiences. This new approach led to changes in programming and the adoption of a new business development strategy, as well as organizational changes. This evolution of the Foundation over the last five years set the backdrop for the evaluation and led to findings in three areas: programming, governance and management, and government relations.

The programming conducted by the Foundation produced solid results that aligned with, and were supportive of, the mandate outlined in the CGA. The broad mandate provided the flexibility required for the Foundation to undertake new and relevant programming that responded to changing contexts. Stakeholders found value in the Foundation's activities, particularly improved awareness of the Asia Pacific region through the publication of a large number of products. In addition, the Foundation played a positive convenor role between peoples and institutions of Canada and the Asia Pacific region through the fostering of various networks. An area identified to help strengthen research programming is a better utilization of the Distinguished Fellows network.

The evaluation found that the Foundation was well managed with a strong governance and organizational structure. The $50-million Endowment Fund, established through the CGA, provided a stable funding base. The Board has done an effective job of governing the Foundation and has made prudent financial decisions over the years. The Foundation has also been successful in mobilizing external funding sources. The organizational structure has evolved to reflect the needs of the current business approach and is well suited for the Foundation's activities. The grant requirement embedded in the CGA has impacted the Foundation's staffing strategy, resulting in the research team comprising a small number of senior staff and a large cadre of junior researchers. While the model provides flexibility for broad-based programming, the grant requirement was found to limit the Foundation's ability to change the staffing model if needed.

While examining government relations, the evaluation found a few areas in need of further clarification. There is a partial misalignment between the Act and the CGA in terms of independence and oversight. Although granted independence through the Act, the Foundation must still comply with a number of CGA and other government policy requirements. Global Affairs Canada's oversight role, and the extent to which the Foundation's work should be consistent with the Government of Canada's priorities, is unclear. In addition, the evaluation found that the Government of Canada has not consistently fulfilled its obligations to the Foundation under the CGA, such as appointing Governor in Council (GIC) Board members on a timely basis. Lastly, communications between the Foundation and the government have largely been ad hoc and transactional, causing an expressed need for more formal communication channels.

Summary of recommendations

APF Canada

- Undertake a strategic review or stock-taking exercise of the current business model in the context of the CGA review, the appointment of a new President and CEO in 2021 and the upcoming changes in the Board membership.

- Be proactive in engaging the Distinguished Fellows. The cohort of Fellows can offer expertise and regional experience to further support the Foundation's work.

Global Affairs Canada

- Clarify the department's oversight roles and responsibilities, or authority framework, with respect to the Foundation.

- Develop a funding framework for GAC to allow more flexibility and timely support of APF Canada to respond to additional departmental needs that fall outside of the CGA.

APF Canada and Global Affairs Canada

- Develop an operations and communications plan to address the requirements of the Act and the CGA, in particular:

- an operations plan that ensures an appropriate timeline for the process of GIC and Ministerial appointments

- a communication and consultation mechanism to allow for the regular exchange of information and the discussion of plans and priorities

Evaluation scope and objectives

Evaluation objectives

The overall objective of the evaluation was to provide neutral and evidence-based feedback to senior management regarding the relevance, effectiveness and efficiency of the Foundation, as well as its relationship with Global Affairs Canada since 2014-15.

In particular, the evaluation aimed to:

- assess the extent to which the activities of APF Canada continue to be aligned with its mandate, comply with the requirements of the CGA, and reflect the priorities of the Government of Canada and GAC for the Asia Pacific region

- assess the effectiveness of the current governance structure and determine whether appropriate management oversight is in place to support the implementation of the CGA and the efficient and effective administration and delivery of APF Canada's programs and activities

- determine the progress made and results achieved against stated objectives and strategic outcomes since 2014

- identify the extent to which GAC and APF Canada have leveraged opportunities for communication and effective collaboration

Evaluation rationale

The Asia Pacific Branch of Global Affairs Canada (GAC) recommended that an evaluation of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) be conducted in line with the provisions of the Conditional Grant Agreement (CGA) signed between the Foundation and the Minister of Foreign Affairs in 2005. As per Section 9(2) of the Agreement, the Minister of Foreign Affairs may undertake, "at the expense of the Department, evaluations of the Foundation by evaluators of his or her choosing". This is the second department-led evaluation of the Foundation; the first was conducted in 2008-09by the Diplomacy, Trade and Corporate Evaluation Division at GAC.

The evaluation process followed the Treasury Board Policy on Results and Directive on Results. In the Government of Canada, evaluation is defined as "the systematic and neutral collection and analysis of evidence to judge merit, worth or value. Evaluation informs decision-making, improvements, innovation and accountability. Evaluations typically focus on programs, policies and priorities and examine questions related to relevance, effectiveness and efficiency."

Evaluation scope

The evaluation covered the Foundation's operations and activities between April 1, 2014, and March 31, 2020. The evaluation also examined the effectiveness of the communication and engagement between the Foundation and the Government of Canada—notably, through GAC. Finally, the scope included a review of GAC's activities in support of APF Canada and examined opportunities for improvement with regard to fulfilling the department's responsibilities under the CGA.

Evaluation approach

The evaluation was conducted in-house by the Evaluation Division of Global Affairs Canada. The team was supported by an independent consultant with extensive evaluation experience and knowledge of GAC, including participation in the 2008-09 evaluation of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada.

An Evaluation Advisory Committee comprising representatives from GAC and APF Canada, including members of the Foundation's Board of Directors, was established as a consultative mechanism to provide the benefit of a transparent evaluation process. The Committee was engaged throughout the evaluation process and provided advice and comments on deliverables.

Concurrent with the evaluation, the firm KPMG conducted an external review of the CGA. The purpose of the review was to update and renew the Terms and Conditions of the CGA. The evaluation and review were coordinated to leverage synergies and avoid duplication.

Evaluation questions

| Evaluation Issue | Questions |

|---|---|

Programming | 1. To what extent do the priorities and activities of APF Canada continue to be consistent with the objectives of the Act and the CGA? 2. To what extent is APF Canada's programming relevant to, and meeting the needs of, its key stakeholders? 3. To what extent has APF Canada achieved its expected outcomes? |

Governance and Management | 4. To what extent has APF Canada established and maintained an effective governance structure? 5. To what extent has APF Canada used its financial and human resources efficiently and in compliance with the CGA? |

Government Relations | 6. To what extent has GAC exercised oversight and acted on commitments as per the CGA? 7. To what extent have relations between APF Canada and GAC been managed in an effective and efficient manner? |

Methodology

The evaluation team applied a mixed-method approach, using a range of data collection and analysis tools to assess each of the proposed evaluation questions. Five main methods were used to conduct this evaluation. See Annex A for additional methodology details and Annex G for a summarized list of sources per section.

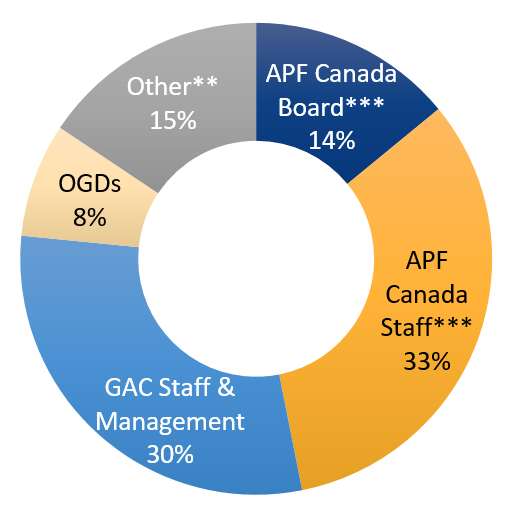

| Key Stakeholder Interviews (n = 64) | Document and File Review | Case Studies | Comparative Analysis | Review of APF Canada Media Analytics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 64 key stakeholders via telephone or teleconferencing platforms. Evaluators interviewed a representative sample of individuals from the following categories:

| The evaluation team conducted an in-depth review of departmental and APF Canada documents and files, including but not limited to: annual reports since 2014, past evaluations and reviews, financial data and statements, strategies, research and policy papers, APF Canada's website, and GAC internal documents and correspondence. The document review provided critical insights into the role and activities of the Foundation, its internal policies and management, financial data, and strategic approach. | APF Canada's 2016 report titled "Building Blocks for a Canada-Asia Strategy" was examined to explore the extent to which the Foundation's reports and policy advice were used by the Government of Canada to inform policy and decision making. This document presented a series of recommendations to the Government of Canada in general and GAC in particular. A case study report was developed to support the analysis of data. In addition, another case study was conducted on the 2020 report titled "Canada and the Indo-Pacific" to compare and contrast with the main case study. | A comparative analysis of APF Canada and other organizations with similar mandates, scope of activities, and resources was undertaken to assess outreach and influence. The comparison focused on a range of metrics such as social media reach, website traffic, publications and citations, and think tank rankings. | A review of APF Canada's analytics through an analysis of social media and hyperlinks provided insight into the usefulness of the Foundation's core activities, as well as identifying trends, demographics, and user preferences. The social media analysis was based on data obtained from the Foundation and considered Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and Instagram metrics over time. The backlink analysis used tools provided by the specialized software Ahrefs to examine user demographics as well as the popularity of APF Canada activities. |

Evaluation limitations and mitigation measures

| Limitations | Mitigation Measures |

|---|---|

| Confidentiality and bias Evaluators from Global Affairs Canada conducted the evaluation of the Foundation. Evaluation participants may have questioned the ability of the evaluators to remain unbiased. In addition, interview participants may have been reluctant to criticize the Foundation for fear of comments being attributed to them or of future impacts on the Foundation. This concern may have resulted in hesitancy by interview participants to provide candid responses to questions. |

|

| Coverage of APF Canada's activities The Asia Pacific Foundation undertakes a large number of activities and programs varying in objectives, making it challenging to evaluate the performance and impact of every activity within the planned evaluation time frame. |

|

| Identification of comparable think tanks The comparative analysis selected nine similar think tanks to compare outputs and other indicators. This proved challenging as there are no identical organizations with the same objectives, undertaking the same activities, or offering the same services. |

|

Program background

The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada

The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada is an independent, not-for-profit organization established by the Asia-Pacific Foundation of Canada Act in 1985 as a result of the Government of Canada's identified need for stronger relations with the Asia Pacific region. The Act laid the basis for APF Canada's purpose, mandate, governance and reporting.

In 2005, the Minister of Foreign Affairs signed a Conditional Grant Agreement (CGA) with the Foundation. The CGA provided a $50-million conditional grant for the establishment of an Endowment Fund to ensure predictability of APF Canada's finances and to allow for longer-term planning. The CGA was also intended to enhance the Foundation's ability to develop a granting program and maintain several formal affiliations with regional organizations to help strengthen Canada's relations across the Asia Pacific region. To ensure that the funds were managed in accordance with the Policy on Transfer Payments, the CGA contained a number of requirements for governance, reporting, programming, and the management and use of the grant.

Mandate

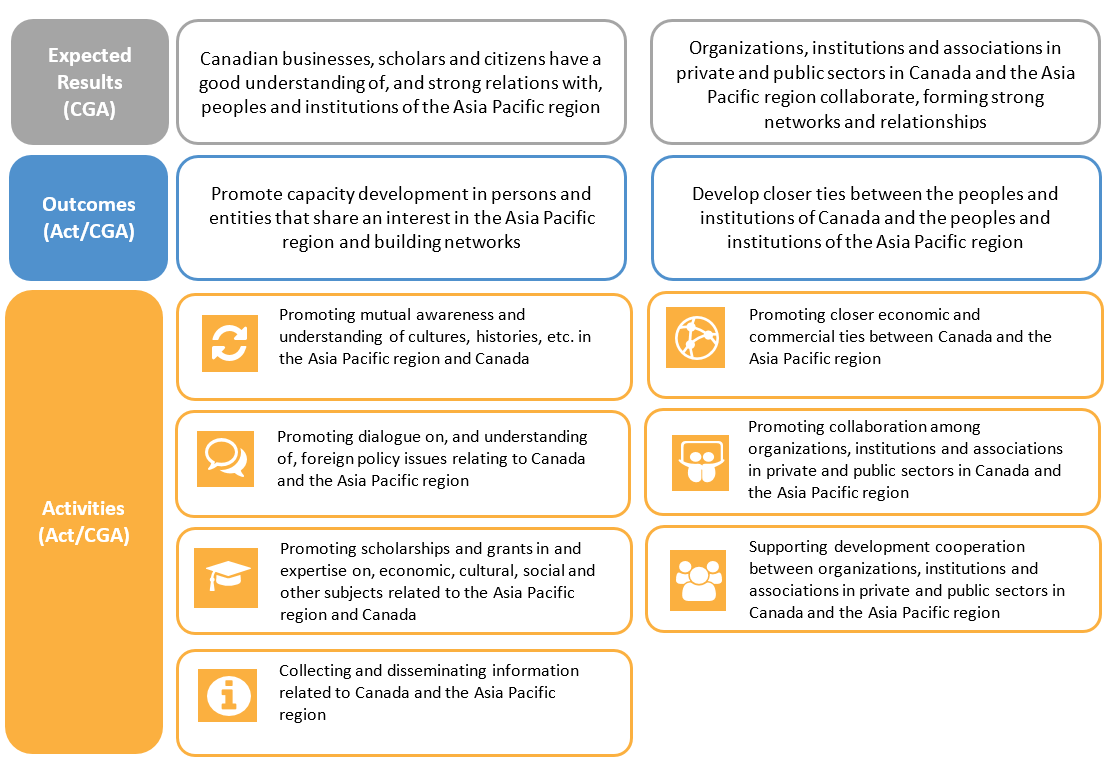

The Act and the CGA clearly outline the Foundation's purpose and mandate, which is in essence to build networks and develop closer ties between the peoples and institutions of Canada and the peoples and institutions of the Asia Pacific region. Figure 1 illustrates the Foundation's theory of change using language from the Act and the CGA.

Figure 1: Theory of change

Text version

(Left Column)

Expected results (CGA):

- Canadian businesses, scholars and citizens have a good understanding of, and strong relations with, peoples and institutions of the Asia Pacific region

Outcomes (Act/CGA):

- Promote capacity development in persons and entities that share an interest in the Asia Pacific region and building networks

Activities (Act/CGA):

- Promoting mutual awareness and understanding of cultures, histories, etc. in the Asia Pacific region and Canada

- Promoting dialogue on, and understanding of, foreign policy issues relating to Canada and the Asia Pacific region

- Promoting scholarships and grants in and expertise on, economic, cultural, social and other subjects related to the Asia Pacific region and Canada

- Collecting and disseminating information related to Canada and the Asia Pacific region

(Right Column)

Expected results (CGA):

- Organizations, institutions and associations in private and public sectors in Canada and the Asia Pacific region collaborate, forming strong networks and relationships

Outcomes (Act/CGA):

- Develop closer ties between the peoples and institutions of Canada and the peoples and institutions of the Asia Pacific region

Activities (Act/CGA):

- Promoting closer economic and commercial ties between Canada and the Asia Pacific region

- Promoting collaboration among organizations, institutions and associations in private and public sectors in Canada and the Asia Pacific region

- Supporting development cooperation between organizations, institutions and associations in private and public sectors in Canada and the Asia Pacific region

Organizational structure and finances

APF Canada's organizational structure and finances have evolved considerably since the previous evaluation conducted by the department in 2008-09, shortly after the Foundation was hard hit by the financial crisis. The Foundation underwent major staffing cuts in 2007 and saw the market value of the Endowment Fund fall below $50 million by October 2008. Since that time, the Foundation has recovered, and various management and structural changes were made between 2008 and 2014, which were not reviewed as part of this evaluation.

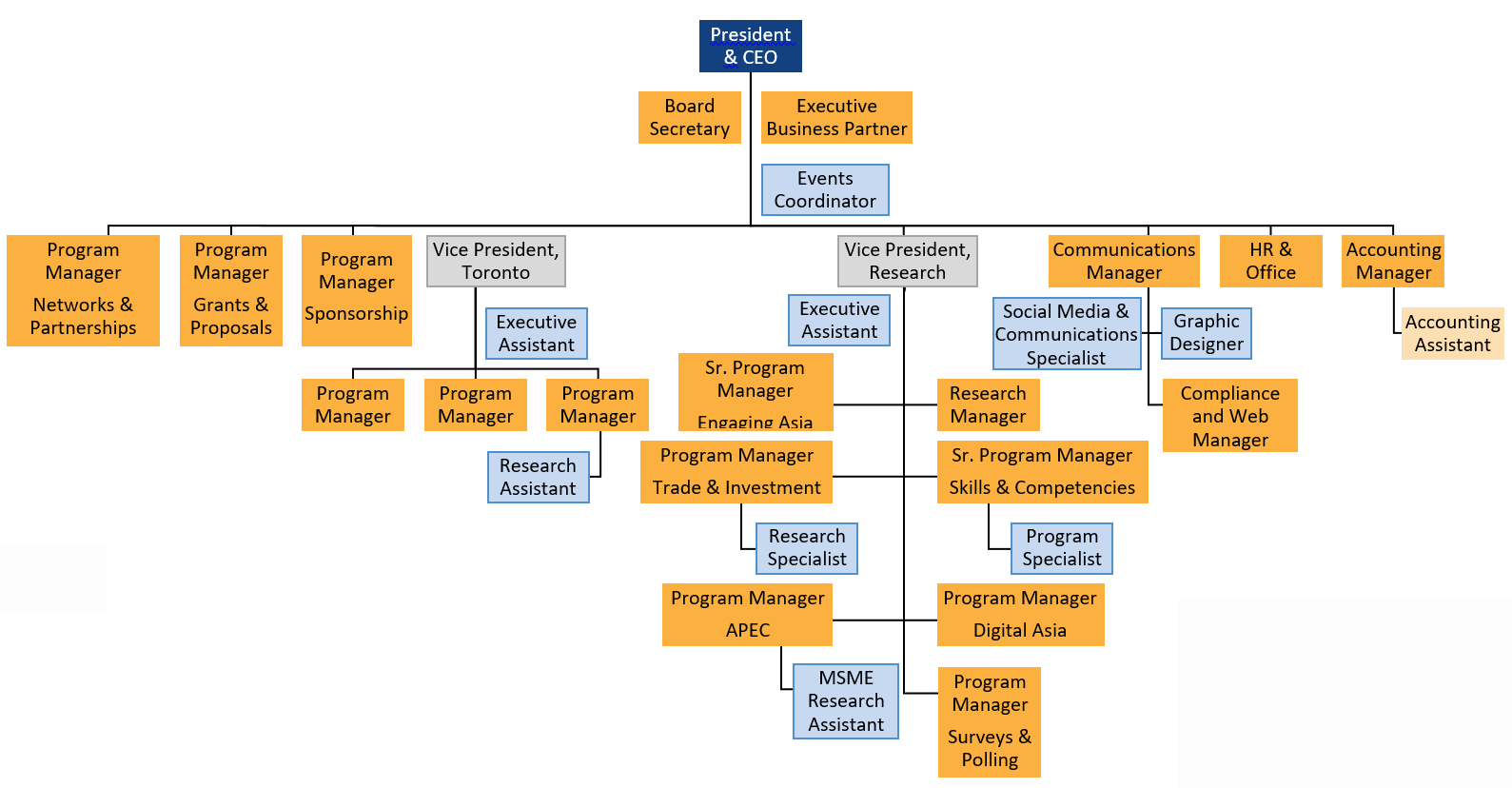

As of 2020, the Foundation is governed by a Board of Directors and managed by the President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO), who provides additional oversight and leadership. There are currently 39 full-time equivalent staff within the organization. Although the organization's main office is based in Vancouver, British Columbia, the Foundation has since expanded to include a satellite office in Toronto, Ontario. See Annex B for an adapted organizational chart as of May 2020.

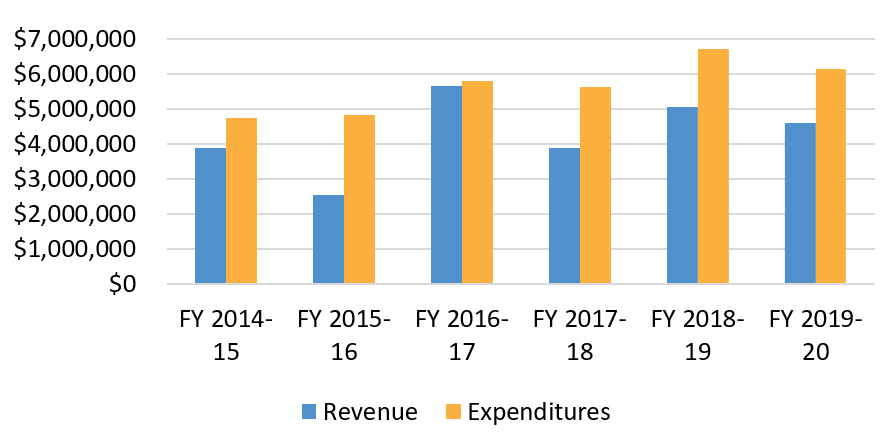

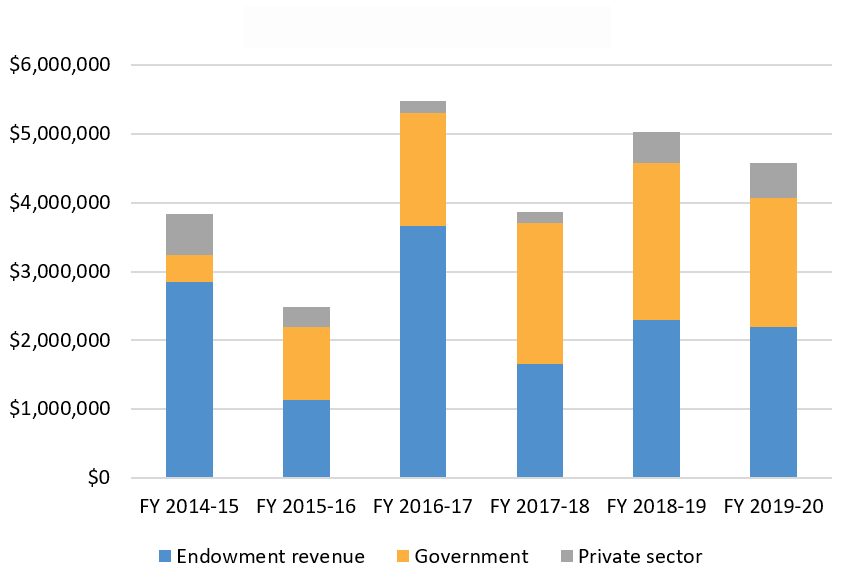

The Foundation is funded through the proceeds of the Endowment Fund and through outside contracts and grants. The yearly budget for the Foundation is approved by the Board and has steadily increased over the last five years as new revenue sources were added. During the evaluation period, the Foundation's expenditures have grown from $4.8 million in FY 2014-15 to a high of $6.7 million in FY 2018-19.

Figure 2: Revenue and expenditures

Text version

Revenue:

FY 2014-15: $3,879,993

FY 2015-16: $2,538,366

FY 2016-17: $5,653,481

FY 2017-18: $3,871,595

FY 2018-19: $5,050,069

FY 2019-20: $4,599,167

Expenditures:

FY 2014-15: $4,755,782

FY 2015-16: $4,817,001

FY 2016-17: $5,789,315

FY 2017-18: $5,638,114

FY 2018-19: $6,715,283

FY 2019-20: $6,129,803

The revenue figures include net investment income for the year from the Endowment Fund along with revenues from other sources, such as government contracts and the private sector. The yearly shortfall is covered by the generation of capital gains on the investments during the year or through draws from the unrestricted funds—investments over $50 million. Investment income fluctuates each year depending on market returns. Even with yearly withdrawals from the unrestricted funds, the investments overall have continued to grow.

The majority of external funding generated has been from government sources. Global Affairs Canada and other Canadian government departments have contributed approximately 60% of the government funds to the Foundation, with the Kakehashi Project, funded by Japan, contributing most of the remaining government funds. The Foundation's two largest government contracts are the $2.3-million GAC-funded Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)-Canada Growing Business Partnership and the $2-million Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED)-funded Women's Business Missions through the Women Entrepreneurship Fund.

Introduction to findings

"With a measured and strategic approach, the Foundation has shifted from a 'think-tank' to a 'do-tank' over the past five years, not only producing research that provides high-quality, relevant, and timely information, insights, and perspectives on Canada-Asia relations, but also working with business, government, and academic stakeholders to provide actionable policy considerations and real-time business intelligence."

APF Canada's 5-Year Organization and Activities Review – 2015-2020

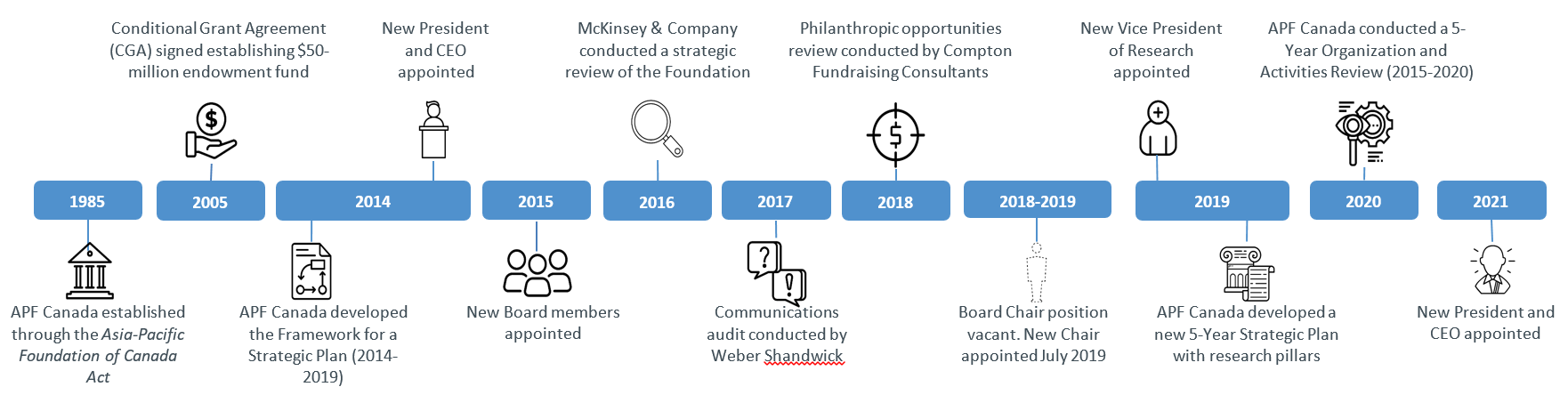

Starting in 2014, the Foundation began to change its business model. With the arrival of a new President and CEO, a decision was made in conjunction with the Board to move the Foundation toward a more action-oriented approach serving broader audiences. Over the evaluation period, changes were made in programming, financing and management of the Foundation to put this model in place.

While major reports and policy briefs continued to be published, new formats and content were developed for products including shorter, more timely analyses such as dispatches, blogs and podcasts. For example, the Asia News Service was transformed to Asia Watch, focusing on providing analysis of news, trends, and issues in Asia.

As part of the transition, APF Canada developed new programming for a range of stakeholders, such as pilot programs on curricula with British Columbia as well as internships and the fostering of new networks.

At the Board's direction, the Foundation adopted a business development strategy that focused on generating additional funding primarily from government sources and on monetizing products and services to match the research and programming agenda, such as the Investment Monitor where subscribers can pay to access specialized data and information.

In addition, the Foundation made a series of organizational changes. Human resources (HR) processes were put in place including an employment manual. The Communications Division was established to develop and manage communications strategies to reach key audiences including through social media. The Foundation reorganized itself to align with the pillars of the new Strategic Plan in 2019.

This evolution of the Foundation over the last five years set the backdrop for the evaluation. The changes made over the period were integrated into the analysis of the findings.

Figure 3: Timeline of key events

Text version

1985: APF Canada established through the Asia-Pacific Foundation of Canada Act

2005: Conditional Grant Agreement (CGA) signed establishing $50-million endowment fund

2014: APF Canada developed the Framework for a Strategic Plan (2014-2019)

2014: New President and CEO appointed

2015: New Board members appointed

2016: McKinsey & Company conducted a strategic review of the Foundation

2017: Communications audit conducted by Weber Shandwick

2018: Philanthropic opportunities review conducted by Compton Fundraising Consultants

2018-2019: Board Chair position vacant. New Chair appointed July 2019

2019: New Vice President of Research appointed

2019: APF Canada developed a new 5-Year Strategic Plan with research pillars

2020: APF Canada conducted a 5-Year Organization and Activities Review (2015-2020)

2021: New President and CEO appointed

Programming

1. The Foundation has adapted to an evolving context, developing new and relevant programming aligned with its broad mandate.

The Foundation's purpose, outcomes, and expected results are outlined in the Act and the CGA. Together, these two documents shape the Foundation's mandate, which covers a number of areas including education, capacity building, economic relations and network-building. Although providing flexibility, the mandate provides limited guidance on areas where the Foundation should focus. This has meant that the evolution of priorities by the Foundation over the last five years has resulted in a wide range of pertinent projects in areas such as energy policy, national security, public health, education, trade promotion, development programming, and more. See Annex C for the Evolution of Strategic Plans.

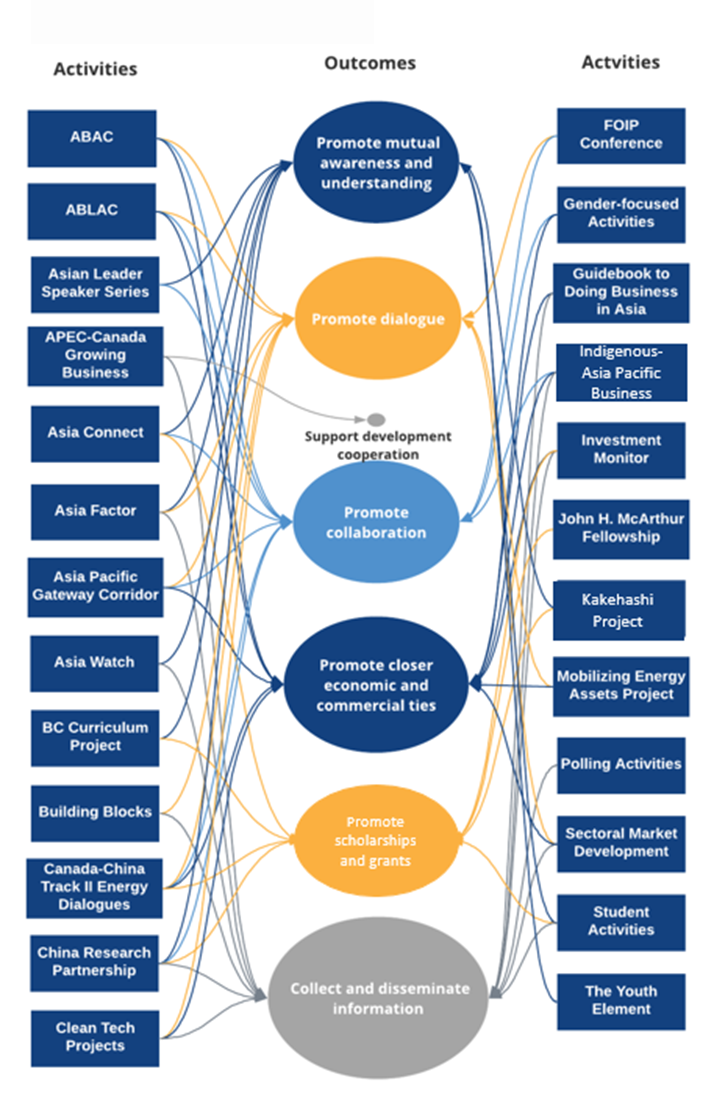

The evaluation conducted an analysis of 25 of the Foundation's activities undertaken over the last five years, known as points of impact. The analysis demonstrated consistency and alignment with the Act and the CGA. Virtually all activities aligned with more than one area of the Foundation's outcomes, with a weight toward promoting economic ties and collecting and disseminating information. For example, the Canada-China Track II Energy Dialogue, a dialogue series that convened government officials and environmental activists and organizations on Canada-China engagement surrounding energy issues, aligned with numerous areas of the mandate. The initiative promoted dialogue and understanding of foreign policy issues related to the region, promoted collaboration among organizations in private and public sectors, and promoted closer economic and commercial ties.

The broad mandate has provided the Foundation with the flexibility to undertake new and relevant programming that would have been otherwise not possible with a more rigid mandate. It has also allowed the Foundation to rapidly respond to changes in the Asia Pacific region. An example is the new "Mapping the Asia Pacific's COVID-19 Response" project launched in 2020, which tracks developments around COVID-19 policy responses in the region. This project aligns with the outcome of collecting and disseminating information and also aims to inform Canada's domestic pandemic response by identifying policy best practices.

The Foundation continues to have a clear niche in Canada as the only organization dealing with regional issues and Canadian relations. While its activities align with its mandate, a range of stakeholders wondered whether the breadth of the areas currently covered was too large given the budget. Was there a trade-off between breadth and depth to having an impact?

Figure 4: Analysis of activities

Text version

Analysis of activities depicts how 25 of the Foundation's activities align with the Foundation's outcomes: 1) promote mutual awareness and understanding; 2) promote dialogue; 3) support development cooperation; 4) promote collaboration; 5) promote closer economic and commercial ties; 6) promote scholarships and grants; 7) collect and disseminate information.

- ABAC aligns with outcomes 2, 4 and 5.

- ABLAC aligns with outcomes 2, 4 and 5.

- Asian Leader Speaker Series aligns with outcomes 1 and 4.

- APEC-Canada Growing Business aligns with outcome 3 and 7.

- Asia Connect aligns with outcomes 1, 4 and 6.

- Asia Factor aligns with outcomes 1, 2 and 7.

- Asia Pacific Gateway Corridor aligns with outcomes 2, 4 and 5.

- Asia Watch aligns with outcomes 1 and 7.

- BC Curriculum Project aligns with outcomes 1 and 6.

- Building Blocks aligns with outcomes 2 and 7.

- Canada-China Track II Energy Dialogues aligns with outcomes 2, 4, 5 and 6.

- China Research Partnership aligns with outcomes 1, 4, 6 and 7.

- Clean Tech Projects aligns with outcomes 2, 5 and 7.

- FOIP Conference aligns with outcomes 2 and 4.

- Gender-focused Activities aligns with outcomes 4 and 5.

- Guidebook to Doing Business in Asia aligns with outcomes 5 and 7.

- Indigenous-Asia Pacific Business aligns with outcomes 4, 5 and 7.

- Investment Monitor aligns with outcomes 6 and 7.

- John H. McArthur Fellowship aligns with outcome 6.

- Kakehashi project aligns with outcomes 1 and 6.

- Mobilizing Energy Assets Project aligns with outcome 5.

- Polling Activities aligns with outcome 7.

- Sectoral Market Development aligns with outcomes 5 and 7.

- Student Activities aligns with outcomes 6 and 7.

- The Youth Element aligns with outcome 1.

2. The Foundation is valued for its activities and programs that have contributed to increased awareness and understanding of the Asia Pacific region.

The Building Blocks for a Canada-Asia Strategy report, released in 2016, highlighted five key drivers of change in Asia and how each presented challenges and opportunities for Canada. While the uptake of the report could not be determined definitively, the report was widely read and continues to be referenced as shown by website backlinks from other organizations and think tanks. The evaluation found the success of the paper was likely due to a number of factors, including:

- incoming Liberal government looking for policy advice as they transitioned to power

- extensive consultations conducted during the development of the report

- reader-friendly format with clear and concise recommendations

- neutral tone maintained throughout the document

- dissemination strategies employed including a series of presentations

- Board engagement to bring the report to relevant policy tables such as the Government of Canada's Advisory Council on Economic Growth

To assess the Foundation's contribution to promoting capacity development on Asia Pacific issues, the evaluation examined 25 activities or points of impact highlighted in the Foundation's 5-Year Organization and Activities Review.

One such program is the Kakehashi Project, which was established in 2013 and was financed by the Japanese government and administered locally by APF Canada. This program provided youth exchanges between Japan and Canada to promote mutual trust and understanding. In total, over 1,000 exchanges have been conducted during the evaluation period.

The Foundation also conducted educational activities such as the development of curricula for middle- to high-school students in British Columbia. The curricula are well regarded as a resource to build Asia competencies for youth. Due to this success, the Foundation is interested in further expanding the curricula to other provinces.

In addition to activities focused on youth, the Foundation has a number of signature products such as National Opinion Polls, Asia Watch, and the Investment Monitor. Feedback on these products indicated that they were valuable tools for a range of stakeholders. Different platforms and products attracted different audiences. For example, a recent survey of Asia Watch readers revealed that a vast majority of the readers were from the private sector (26%), government (21%) and academia (23%). On the other hand, Twitter followers and visitors to the website had less representation from these three groups and more by the general public. LinkedIn provided the highest engagement rates and catered to professionals. The evaluation conducted a backlink analysis to determine the types of stakeholders referencing or linking to the Foundation's web pages on their websites. The analysis found that the online resources made available by the Foundation were primarily linked to by the general public, followed by business and academia. Overall, stakeholders interviewed viewed these products as useful and providing value.

Lastly, the Foundation's activities included contracted policy work by government and business stakeholders that provided insightful information and analysis on the region's markets. For example, one of the points of impact highlighted by the Foundation was Sectoral Market Development where the Foundation researched and published papers on topics such as liquefied natural gas markets in Asia and artificial intelligence.

Overall, the evaluation found that the Foundation's activities were successful in contributing to the promotion of capacity development in persons and in entities sharing an interest in the Asia Pacific region.

3. The Foundation's numerous publications have not translated into a high global think tank ranking.

According to the Act and the CGA, only part of the Foundation's mandate is directly related to research—to promote dialogue on and understanding of foreign policy issues and to collect and disseminate information. With a shift to the new business model, the Foundation stated that it aims to provide high-quality research as well as actionable policy considerations and business intelligence by working with stakeholders. While these objectives are in line with the work of global think tanks, the Foundation does not rank high when compared to other think tanks.

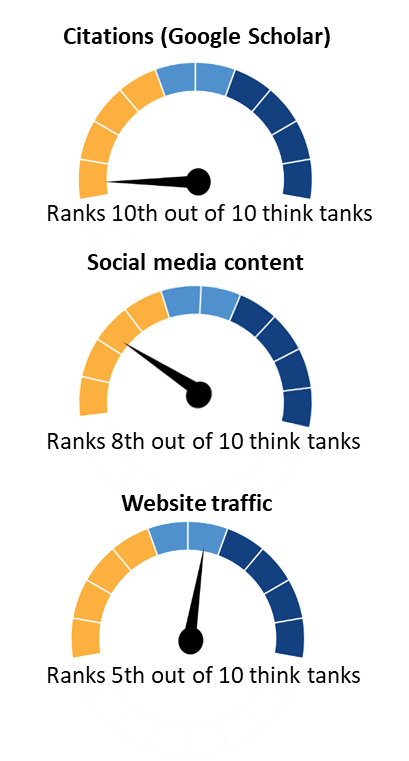

A think tank can be defined as an organization that engages in public policy research, analysis, and engagement to provide advice on issues to policy-makers and the public to help them make informed decisions. The evaluation conducted a comparative analysis between APF Canada and nine other think tanks of similar size and focus to assess the Foundation's outreach and influence. The comparison included metrics such as social media reach, website traffic, as well as publications and citations. While the Foundation ranked tenth for academic citations of its work on Google Scholar, it ranked eighth for social media content and fifth for website traffic, demonstrating its growing outreach efforts. It is important to note, however, that there were limitations in this analysis such as finding comparable organizations with similar funding models, objectives and activities. See Annex D for additional details on the comparative analysis.

The Global Go to Think Tank Index, based on an international survey of scholars, public and private donors, policy-makers, and journalists, ranks more than 6,500 think tanks using a set of 18 criteria. Metrics include peer ranking, public nomination, quality and reputation of leadership and staff, as well as academic performance and reputation including number and reach of publications. The 2020 report ranked APF Canada 38th out of 44 Canadian and Mexican think tanks. The ranking could be linked to the Foundation's focus and capacity to conduct more action-oriented policy work rather than developing academic, peer-reviewed research papers.

The Foundation has acknowledged its lower ranking among global think tanks, but does not believe the ranking is a true representation of its value. For example, the benchmarks used in the indexing model do not align with the Foundation's strategic plan and its priorities to provide more action-oriented research and business intelligence. The Foundation therefore did not see any value-added in focusing efforts on improving its ranking.

An option to increase the reputation of its research could be to better engage Distinguished Fellows. The Foundation has a network of Distinguished Fellows in place, which represents an important pool of expertise. The Fellows are subject-matter experts in various aspects of Canada-Asia relations and are available to provide a range of support including participating in dialogues and public events, providing commentary, responding to domestic and international media requests, and informing research projects. However, wide variations were seen in the involvement of the Fellows in various activities since the Foundation often relied on the Fellows to be proactive in how they wanted to engage. This has meant that the Foundation has not always leveraged the expertise of the Fellows effectively to provide support and guidance for the Foundation's research and policy work.

The evaluation found that while the Foundation's comparative think tank ranking is low, the Foundation has chosen to focus its efforts on producing a large amount of varied content, which is well aligned with its strategic plan and the Board's desire to produce content relevant to Canadians. Nonetheless, more effective approaches could be employed to better engage the Distinguished Fellows to support the Foundation's policy and research work.

Figure 5: APE Canada think tank comparative ranking

Text version

Figure 5 depicts APF Canada's think tank ranking in three categories. For academic citations on Google Scholar, APF Canada ranks tenth out of ten comparable think tanks. For social media content, APF Canada ranks eighth out of ten comparable think tanks. For website traffic, APF Canada ranks fifth out of ten comparable think tanks.

4. The Foundation has developed a positive convenor role through networking activities intended to contribute to developing closer ties between the peoples and institutions of Canada and the Asia Pacific region.

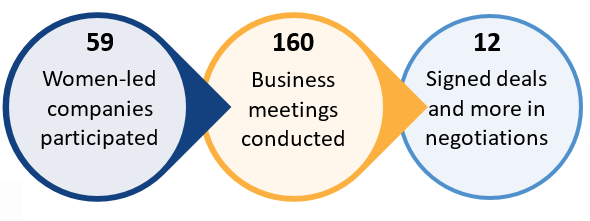

Over the past five years, APF Canada conducted several activities that contributed to building networks and developing closer ties. One such initiative was the Women's Business Missions, which has led, to date, to 12 deals between Canadian and Asian women entrepreneurs and businesses. These missions were piloted in Japan in 2019 as the first gender-based mission to Asia and have now been expanded to other economies such as South Korea and Taiwan. Female entrepreneurs were provided the opportunity to network with Asian partners while promoting their products or services to an international market.

Another set of network-building activities conducted by the Foundation as part of the CGA requirements was providing secretariat services to the Canadian members of the APEC Business Advisory Council (ABAC) and the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC). As part of the services provided, the Foundation supported the Canadian members in meetings and provided reports and summaries as needed. Both councils provided recommendations and promoted dialogue and cooperation between the members of the international network. The support provided by the Foundation to the Canadian members was highly regarded and was seen as contributing to policy and business development for Canada. While the CGA stipulates that the Foundation should provide secretariat services to these councils, it does not specify what costs the Foundation should cover for its secretariat work from the Endowment Fund and what costs are outside of the agreement. This lack of clarity has led to confusion and to several requests for additional resources to GAC and other sources to cover costs associated with conferences convened, but not considered by the Foundation as part of the secretariat work funded by the Endowment.

Created in 2016, the Asia Pacific Youth Council brings voice to Canadian youth interested in Canada-Asia relations. The program, which started in Vancouver and has since expanded to include a group from Toronto as of 2019, allowed youth members of the Council to share their perspectives on Canada-Asia topics with the Foundation. Both groups supported the Foundation in reaching a younger audience and led youth-oriented outreach and events.

Figure 6: Results from the women's business missions to date

Text version

- 59 Women-led companies participated

- 160 Business meetings conducted

- 12 Signed deals and more in negotiations

Another initiative by the Foundation was the inauguration and leading of the annual Asia Business Leaders Advisory Council (ABLAC) meetings since 2016. These high-level meetings brought together approximately 30 Canadian and Asian business and government leaders annually to create dialogue on strategic policy and build stronger relations and opportunities between Canada and Asia. The meetings touched on the economic relations between Canada and Asian nations relating to issues such as trade, technology, and sustainability. The Council is regarded as important by participants and the Foundation.

The CGA also called for the Foundation to act as the APEC Study Center of Canada. There are over 50 APEC Study Centers around the APEC region. Until 2019, the Foundation undertook few activities related to this requirement. However, since 2019, it is actively engaging with a number of APEC study centers and establishing work plans.

To better understand its reach, the Foundation conducts its own extensive media and social media monitoring and analysis. Although the Foundation's mission is to be Canada's catalyst for engagement with Asia and Asia's bridge to Canada, most of the Foundation's content was created in English, therefore all social media platforms, except for LinkedIn, are currently not accessible in many Asian countries without the use of a virtual private network. A communication audit in 2017 identified methods to increase the Foundation's reach, which the Foundation has been applying. The latest figures provided by the Foundation demonstrated that its reach has expanded over the evaluation period. Web visits and page views increased by 26% and 68%, respectively, while social media engagement numbers grew across various platforms including Twitter (+75%), Facebook (+86%) and LinkedIn (+9%). In addition, newly adopted platforms such as Instagram and YouTube have also experienced growth.

While the Foundation could put further effort into expanding its reach to become Asia's bridge to Canada by translating content into other languages or joining Asian-based social media platforms, the evaluation found that, overall, the Foundation's activities have contributed toward the building of networks and the development of closer ties between the peoples and institutions of Canada and the Asia Pacific region.

Governance and management

5. Over the past five years, the Foundation has managed the Endowment Fund well and made prudent financial decisions.

The Board, and specifically the Investment Committee, oversees the management of the Endowment Fund. A Statement of Investment Policy and Procedures is in place covering all the requirements listed in the CGA. In 2018, an independent firm was retained to assess the performance of the Fund and provide reports to the Board and the Investment Committee. These reports contain detailed analysis of the investment portfolio including its overall performance, analysis of returns compared to the market and commentary on market fluctuations that may impact the portfolio.

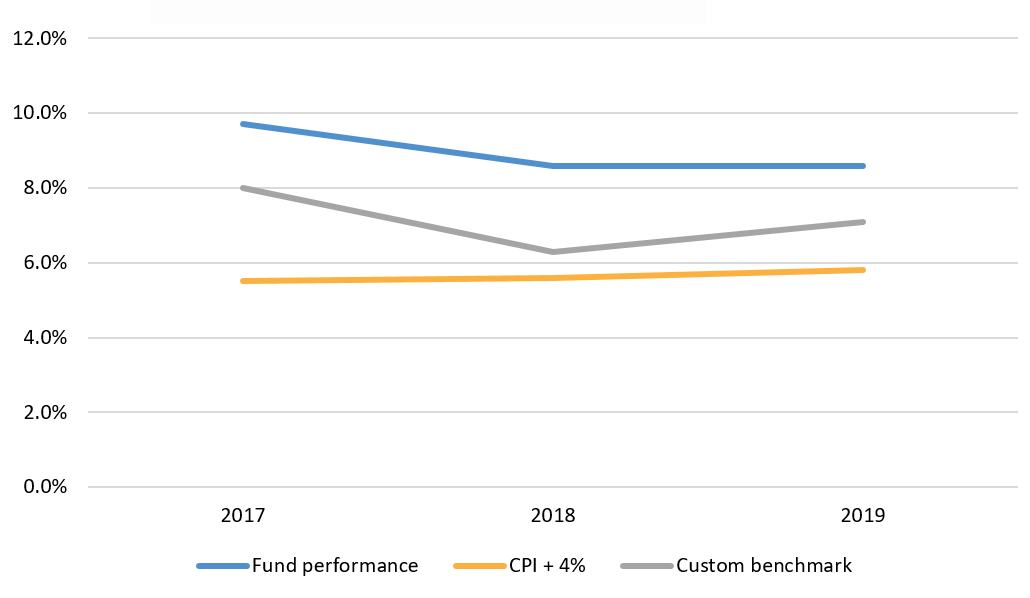

Figure 7: Rates of return against objectives

(4-year rolling average)

Text version

Fund performance:

2017: 9.7%

2018: 8.6%

2019: 8.6%

CPI + 4%:

2017: 5.5%

2018: 5.6%

2019: 5.8%

Custom benchmark:

2017: 8.0%

2018: 6.3%

2019: 7.1%

Two benchmarks are used to track the portfolio—Consumer Price Index (CPI) +4% and a custom benchmark based on the Fund's asset mix. On a four-year rolling basis, the Fund has outperformed both benchmarks. The Fund was also able to quickly recover from the 2020 market adjustment and has grown from $63.7 million in 2014 to over $72 million in 2021.

The Endowment Fund provided the Foundation with a base of funding that paid for operational and some programming costs as well as administering the grants program and secretariat work. The amount of annual distribution coming from the Endowment Fund has fluctuated between $3.4 million and $3.96 million per year during the evaluation period, based on the level of expenditure. The Board reviewed the returns on the Endowment and the potential future market volatility and decided to cap annual spending from the Fund to preserve the capital base. Caps of $3.5 million in 2020-21 and $3.25 million going forward were set, with further funding having to be mobilized from external revenue sources.

The CGA requires that 25% of the revenue of the Endowment Fund goes toward funding a grants program. The CGA was vague, however, on what "revenue" meant or how it was to be calculated. The Board decided in 2015 to move to an accrual system of accounting and set the grant level per year at $360,000 based on a rolling three-year average of income. This rolling average was established following changes in asset allocation in the Foundation's Endowment, which created unexpected revenue spikes that would originally have to be spent on grants in a single fiscal year. In April 2019, the Board sought to clarify the definition of "investment revenue" in relation to the CGA. The Foundation put forward a recommendation to GAC to exclude realized gains on investments from the calculation to allow these to be used to recapitalize the Endowment Fund. GAC approved that change in 2020.

Overall, the Endowment Fund has provided a stable base of funding, and the Foundation has managed the Endowment Fund well over the past five years. The changes to the grant allocations and calculations allowed the Foundation more flexibility in its funding model while maintaining a strong grants program. However, the evaluation found a lack of clarity in the CGA on the process for making and approving amendments such as those for the grant calculations.

6. The Foundation has been successful in mobilizing funding outside the Endowment Fund since 2014-15.

The latest 5-year Strategic Plan published in 2019 projected that the annual expenditure levels would continue to be approximately $6.0 million going forward. To support this level of expenditure required a continuing strong performance by the Endowment Fund and an increasing diversity of outside revenue from government and other sources.

During the evaluation period, an emphasis had been placed on expanding outside revenue sources. The Foundation was successful in this endeavour with the total non-Endowment revenue growing by over 130%. An independent study in 2018 on the potential for fundraising from the private sector indicated that there were limited opportunities. Most of the private sector funding received has been related to co-funding specific events.

The business development approach then focused on obtaining resources primarily from government sources. The proportion of total revenue coming from government sources (Canadian and foreign) grew from 10% in 2015 to a high of 53% in 2018. The funding was received from a wide range of government departments and agencies including GAC. For example, over the past five years, GAC has funded 19 projects for a total of $3.15 million.

Figure 8: Sources of revenue

Text version

Endowment Revenue:

FY 2014-15: $2,845,774

FY 2015-16: $1,136,100

FY 2016-17: $3,667,699

FY 2017-18: $1,652,972

FY 2018-19: $2,293,523

FY 2019-20: $2,191,994

Government:

FY 2014-15: $398,974

FY 2015-16: $1,058,380

FY 2016-17: $1,631,293

FY 2017-18: $2,047,635

FY 2018-19: $2,291,011

FY 2019-20: $1,879,461

Private sector:

FY 2014-15: $595,576

FY 2015-16: $293,301

FY 2016-17: $187,585

FY 2017-18: $170,813

FY 2018-19: $449,300

FY 2019-20: $511,391

However, many of these government contracts were of low value with a median value of approximately $25,000. These small contracts resulted in high transaction costs for both the Foundation and the government departments, making the contracts less efficient to administer. The 2016 Strategic Review indicated that small-scale proposals were valuable when they created a runway for future work, but otherwise could have a low return on investment by consuming significant management capacity. In addition, as the scope of Canada's interests and business needs within the region evolves based on emerging priorities, government stakeholders highlighted the lack of flexible funding mechanisms for GAC to swiftly task and fund APF Canada to undertake projects and activities that may not be explicitly supported by the CGA.

On the other hand, the multi-year contracts sourced by the Foundation provided funding stability for a particular programming area and longer time frames to achieve results. The Kakehashi Project has been in place since 2013; the APEC-Canada Growing Business Partnership has been in place since 2016, and the Women's Business Missions since 2019. For the latter two, counterpart funding was required under the contracts, and only certain costs were covered. This meant that the Foundation needed to use part of the $3.25‑million Endowment Fund allocation to cover the projects. The Foundation's overall budgets for the last three years indicate that contracted projects took from 4% to 12% of in-kind distributions from the Endowment Fund. Projects that are pursued should therefore be strategically selected and provide value to the Foundation beyond simply adding incremental revenue, otherwise there could be opportunity costs where less funding may be available for core products and services or for other initiatives that may be more important to the Foundation.

While the Foundation has been able to generate substantial outside revenue, which supports the intention of the CGA, some trade-offs are seen with the sources and scale of some of the funding.

7. The Foundation has established a strong governance structure, and the Board has been active in key decision making.

APF Canada Act:

Appointments to the Board should consider:

(a) the need to ensure, as far as possible, that at least one half of the membership has experience or expertise concerning relations between Canada and the Asia Pacific region

(b) the need for a membership that has sufficient knowledge of corporate governance, investment management, auditing and evaluations

(c) the importance of having a membership that represents Canadian society

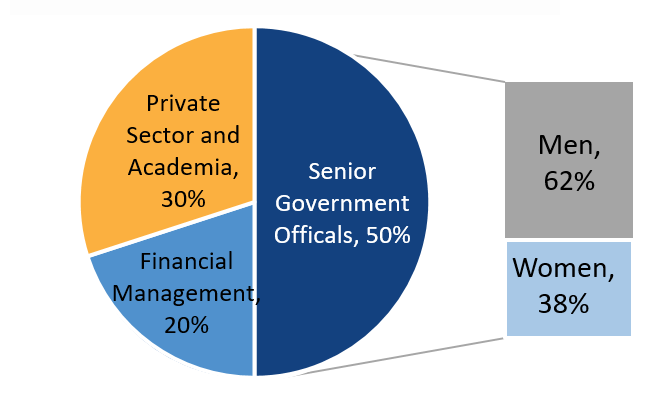

Figure 9: Board membership by sector and gender

Text version

Men: 62%

Women: 38%

Senior Government Officials: 50%

Private Sector and Academia: 30%

Financial Management: 20%

The evaluation found that the Foundation's Board members were highly engaged. The Board met biannually with strong attendance. The CGA's requirements for committees and composition have been fully met with the establishment of four committees—Executive; Governance, HR and Compensation; Investment and Revenue; and Audit and Evaluation. There was consistent reporting by the four committees to the Board. In addition, to improve efficiency, the Foundation had made changes to the committee structure, such as combining the Compensation and Governance committees in order to better balance committee membership and offset the gap in government appointments to the Board.

The Board has been active in the development of the new business model, supporting the push for outside funding and approving the operational and programming approaches and the new Strategic Plan. In 2016, an external strategic review was undertaken that provided Board members an opportunity to review feedback from stakeholders and better understand trade-offs in implementing the new approach. The move to the new business model was seen as a way to make the Foundation more sustainable and enhance its impact.

To select new Board members, a Board matrix was developed and implemented. This served to improve representation, diversity, and obtain a spectrum of people on the Board. The resulting Board members are prominent, well connected individuals who are able to promote the Foundation and its work in various circles. Some 50% of the Directors in 2020 were former senior officials of the federal and provincial governments including ex-ministers and an ex-premier. Some 20% were in financial management, and the remaining 30% were from the private sector and academia. Women comprised 38% of the Board membership.

While there have been improvements toward gender and geographic representation on the Board, the Board itself recognizes the potential for further improvement. There is an opportunity for change, such as adding civil society representation or more individuals with Asian backgrounds, as the terms of several Board members will end in 2021.

Overall, the governance structure has worked well. The Board members provided both guidance and expertise that has proven valuable to the Foundation and its achievement of outcomes to date.

8. The Foundation's organizational structure has evolved to reflect the new business model, resulting in four high-functioning divisions.

As the business model evolved over the last five years, changes were made to the mix of staff, how they were organized, and the HR policies. A Business Development Team was organized, and a Communications Manager was hired. A new Vice President of Research was selected in 2019 with geopolitical skills to support the broadening focus. HR policies were developed, and an HR Manager engaged. This evolution culminated in a new organizational structure in 2019 that reflected the needs of the current approach. The new structure saw the removal of the Vice President of Operations and Networks position and the shift to four divisions—Office of the President; Research Division; Toronto Office; and Communications Division. Feedback from the staff indicated that, after an initial adjustment to the new structure, it is now working well.

Figure 10: Organizational chart by functions based on May 2020 chart

Division – Office of the President

| Division – Research

| Division – Toronto Office

|

Division – Communications

|

Office of the President

The President and CEO remains the decision maker for both the strategic planning and the daily operations. The flat organizational structure adopted means that one third of the staff now directly report to the President. Besides the three Division heads, the President also directly supervises the activities around business development, networks and secretariats, grants program, HR and finances.

Research Division

The Research Division is structured in teams based on the Strategic Plan pillars or projects that meet the needs of a specific stakeholder. The senior research staff are responsible for the continuity of the teams' programming. This structure has allowed for flexibility to operate projects independently and create expertise and efficiency within the individual teams. However, the evaluation found that building a research team around the expertise of a specific senior researcher may be difficult for long-term planning when an employee with the specific expertise leaves the Foundation for other opportunities. For example, the research under the Sustainable Asia pillar is an important and relevant area of focus for the Foundation, but major projects under this pillar have slowed down since 2019 as the program manager position remains vacant.

Toronto Office

The Vancouver and Toronto offices run separate programs with Toronto handling two of the largest projects—Kakehashi Project and the Women's Business Missions—as well as other activities. Until 2020, there was coordination between Vancouver and Toronto around specific events or meetings such as ABLAC, but more limited collaboration between the offices in general. With the pandemic, weekly virtual staff meetings were instituted, which staff have described as improving communication and coordination between the two offices.

Communications Division

The Communications Division has developed a brand for the Foundation and rapidly expanded its social media presence. In 2015, the approach to communications was relatively ad hoc and relied on written documents and pamphlets. Since that time, the Division has developed a wide range of communications tools that have been tailored to different audiences and platforms, making the information more accessible. The Foundation has put in place a detailed monitoring system to review performance of a wide range of indicators on a monthly basis.

In general, the evaluation found that the revised organizational structure is well suited to manage and undertake the Foundation's wide range of activities.

9. The grant requirement in the CGA has impacted the Foundation's staffing model, increasing the reliance on young professionals.

The Foundation's approach to staffing its research program has relied on a small number of senior full-time researchers as well as a large cadre of junior and young professionals who have not done substantive research outside of an academic environment. This was partially driven by the grant program requirement in the CGA. While the turnover of permanent staff has been low, the fixed-term contract and grant recipients have been hired for short terms. Over the evaluation period, the grants program was used to hire 29 Post-Graduate Research Fellows (PGRF) and 56 Junior Research Fellows. While some of those receiving grants have stayed with the Foundation, a majority were there for short periods, sometimes as short as a few months.

The Foundation's grants program has provided the PGRFs with an opportunity to undertake research and gain experience. The program has been popular as demonstrated by the frequency of website traffic on the grants program web page, social media engagement, and the number of applications received. The PGRFs are required to provide program support in addition to their research and were chosen based on the extent to which their proposed research topics complemented the Foundation pillars and products. Prior to the pandemic, the frequency of travel each could undertake decreased. This, combined with the workload of program support, has sometimes resulted in some of the PGRFs being unable to finish research projects. In addition, current and former staff drew attention to the limited opportunities for career progression, prompting their move to the public sector or other organizations with stable, long-term job opportunities.

The staffing model of hiring many young researchers has suited the broad-based approach the Foundation has taken with respect to its programming. These researchers were able to support ongoing programming as well as pursue new areas of research. The Foundation was highly regarded by current and former staff, as well as by other stakeholders, as a training ground for the next generation of Asia Pacific experts. However, with the rotation of numerous young researchers hired only to work on specific projects, the Foundation has struggled with building longer-term institutional capacity and leveraging expertise developed in one project to other areas of the organization. Moreover, with the CGA requirement of $360,000 going to grants, it would be difficult to move to a different staffing and programming model if the Foundation chose to. For example, another option would be hiring more senior experts for specialized programming with fewer junior staff, as seen with other think tanks. With the grants program embedded in the CGA, the staffing options become more limited making it difficult to move to a different staffing model.

The evaluation found that the staffing model generally supports the current approach to programming and provides a unique opportunity for young professionals interested in gaining research experience in Canada-Asia relations. However, the CGA grant requirement makes changes to the staffing model difficult if the Foundation sought to hire additional senior researchers to focus on developing more specialized programming.

Government relations

10. There is a partial misalignment between the Act and the CGA in terms of independence and oversight.

Independence

The Act established the Foundation as independent, where it is not an agent of Her Majesty nor is it owned by the Crown. The Foundation is governed by a Board of Directors and is not part of the Financial Administration Act, where its employees, Directors, and Chairperson are not considered part of the federal public administration.

Oversight

The Act provides the Minister of Foreign Affairs with the responsibility for recommending the Chairperson and up to four other Directors through Governor in Council appointments, as well as tabling the Foundation's annual reports and five-year reviews in Parliament. The CGA further stipulates that the Minister of Foreign Affairs is responsible for reviewing a number of CGA requirements and is entitled to end the agreement and dispose of funds at his or her discretion. The Minister may also undertake an audit or evaluation at the expense of the department.

The Foundation's independence was established in the Act, while the CGA provided the Minister of Foreign Affairs with a number of oversight responsibilities. The evaluation found inconsistencies between stakeholders' understanding of roles and responsibilities with respect to the independence of the Foundation and the oversight responsibilities of Global Affairs Canada.

The Endowment Fund provided through the CGA is subject to the Policy on Transfer Payments, which aims to ensure that "transfer payments are managed in a manner that respects sound stewardship and the highest level of integrity, transparency, and accountability." Under the Directive on Transfer Payments, there are a number of provisions for upfront multi-year funding for which departmental managers are responsible for addressing in the funding agreement. The CGA includes these necessary provisions and provides the Minister a certain amount of oversight responsibilities to ensure compliance with a number of requirements.

Both the Act and the CGA indicate that the Minister must be provided copies of annual reports, strategic plans, corporate plans, audits and evaluations that may be tabled before Parliament. However, neither the Act nor the CGA reference the responsibility of the department to ensure compliance, which would allow GAC to advise the Minister whether or not CGA conditions are being met. The Policy and the Directive on Transfer Payments also do not clearly outline the department's responsibility to ensure compliance with specific provisions. The CGA requires that the Foundation's annual reports include 12 specific areas of information. However, the department has raised questions as to whether GAC can request changes to the annual reports to better comply with the CGA, or if this type of request conflicts with the independence provided in the Act.

The evaluation found that, in a few cases, the Foundation had only partially met the CGA requirements. This may be a result of duplicated or overlapping requirements listed in the CGA. For example, Section 5.11 of the CGA states that the Foundation agrees to carry out an evaluation of its activities by an independent third party every five years, to be approved by the Board, while Section 9.1 requires the Foundation to conduct follow-up evaluations every three to five years. Furthermore, Sections 9.1 and 9.2 provide the Minister with the authority to undertake evaluations at the expense of the department. See Annex E for a list of evaluation requirements as per the CGA.

In response to these requirements, the Foundation has prepared and submitted internal annual evaluations to the Board, as well as a 5-Year Organization and Activities Review published in 2020, meeting some of the CGA requirements. However, the evaluation standards used for internal reports did not meet the Government of Canada's definition of evaluation. In addition, the Foundation developed terms of reference for the Audit and Evaluation Committee. The terms do not clearly define evaluation, instead refer to performance evaluation of the Committee itself rather than the performance of the Foundation's activities. Lastly, the Foundation hired an independent third party to undertake a strategic review in 2016 that looked at areas such as governance, management and performance; however, the final report was not published.

The evaluation also found that the Foundation has only partially met requirements for the content of its strategic plans and annual reports. Both Foundation and GAC stakeholders interviewed identified a need to clearly define the requirements listed in the CGA as well as determine if certain requirements are still relevant and whether they should be embedded within the CGA.

11. The Government of Canada has not consistently fulfilled its commitments to the Foundation under the CGA.

As outlined in the Act and the CGA (and Annex F), the Minister of Foreign Affairs has a number of responsibilities related to governance and reporting. Over the five years covered by the evaluation, the Government of Canada did not fill the designated Governor in Council (GIC) appointments to the Foundation's Board of Directors in a timely manner. Staff and organizational changes at GAC meant that recommendations by the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the appointments were not put forward for approval, which had several implications.

The delayed appointments left gaps in various committees, affecting the Foundation's compliance with the CGA. This led to the Foundation appointing several Board members, which resulted in a large Board once the GIC appointments were made. In July 2019, the Government of Canada made appointments to replace the Chairperson and three Directors through the new open, transparent and merit-based approach to GIC appointments.

Other areas where the department did not effectively fulfill its commitments to the Foundation were related to the appointment of Canadian representatives to certain councils. The chair of the PECC has been in place since 2008 without an official appointment by the Government of Canada. Furthermore, GAC had not appointed all three members to the ABAC during the evaluation period, which has raised questions about Canada's commitment to these councils and general interest in the region. Despite the fact that the department has recently begun the process for appointing additional ABAC members, only one member has been appointed as of July 2021.

The evaluation found that over the past five years, GAC's engagement with the Foundation has been inconsistent. The liaison or oversight role in the department has changed over time, moving from one branch to another, based on individual interest or experience with the Foundation, rather than on a defined role. GAC staff were therefore not well versed on the conditions of the Endowment Fund and the number of contracts into which the Foundation has entered. Moreover, since 2011-12, GAC no longer reported on the upfront multi-year funding provided to the Foundation in its annual Departmental Results Report.

Lastly, there was no internal Government of Canada coordination regarding the funding strategy for the Foundation. There was no mechanism within the Government of Canada or particularly within GAC to collectively monitor the contracts granted to the Foundation. Government stakeholders interviewed were unaware of the number or total value of government contracts the Foundation had, despite the information being publicly available through government open-source data as well as through the Foundation's annual reports. The absence of a whole-of-government funding strategy for the Foundation has resulted in the funding of multiple one-off projects. At the same time, several GAC employees experienced barriers when trying to arrange for additional funding to the Foundation, outside of the CGA, to swiftly finance new opportunities within the region. Those interviewed expressed a need for more flexibility in the funding arrangement with the Foundation to allow for the expedient support of new and emerging priorities.

12. The extent to which the Foundation's work should be consistent with the Government of Canada's priorities is not clearly understood and may have impacted the Foundation's independence.

In 2020, the Foundation produced a number of outputs related to Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP):

- hosted a conference and published a summary report with support from the Embassy of Japan in Canada, Global Affairs Canada, the Department of National Defence, and other corporate sponsors, which brought together global experts to discuss issues around governance, economics, security, as well as FOIP's applicability to Canada

- published the policy paper "Canada and the Indo-Pacific: 'Diverse' and 'Inclusive' not 'Free' and 'Open'", which was subsequent to the conference and presented the Foundation's independent views on the topic

- drafted a peer-reviewed essay assessing the strategic implications for Canada and FOIP, which was published in the journal Asia Policy

The Foundation was critiqued on its subsequent policy paper as it was not seen as consistent with the Government of Canada's approach to the region at the time. APF Canada staff and external stakeholders interviewed noted the difficulty in finding a balance between meeting the needs of the Foundation's stakeholders while also producing independent views could put the Foundation at risk of being considered as an arm of the government, or potentially at risk of losing funding opportunities. The current decision by the Foundation to remain neutral in other policy debates had supporters as well as detractors both within and outside the Foundation.

A wide diversity of needs for policy research and advice exists within the Government of Canada. While the Foundation has found success in delivering some policy products, especially under specific government contracts, the overall lack of clarity regarding the expectations for the Foundation's policy work made it difficult to assess the extent to which the government's and other needs were being met.

In order to better meet needs, the CGA specifies that the "Foundation's Strategic Plans must be consistent with the Government of Canada's priorities with regard to the Asia Pacific region." The evaluation found an expectation by government stakeholders that the Foundation undertake research and provide policy advice for their consideration. However, federal government stakeholders have expressed either unfamiliarity with the Foundation's recent policy products or views that the products had not met their needs and that they were likely to consult other think tanks working on Asia Pacific issues.

Stakeholders interviewed, including APF Canada and GAC staff, noted the difficulty with striking a balance between being consistent with Government of Canada priorities and developing policy work that may or may not align with the government's current views. There was an understanding by stakeholders that the Foundation was independent and able to present policy options that differ from the current government's views. However, the Foundation has experienced a critique of its work when an opposing view was presented.

Both the Foundation and the Government of Canada have made their strategic priorities publicly available to a certain extent. The CGA includes a provision in Section 5.6 for the Foundation to develop and implement a results-based Strategic Plan in consultation with its clients and stakeholders. However, the evaluation found that the Foundation's strategic plans were developed internally without significant consultations with GAC. Government stakeholders interviewed stated a lack of understanding of or familiarity with the Foundation's current strategic plan and priorities exists, despite the fact that the Foundation published its priorities, including overall strategic pillars, on its website and within annual reports in both official languages. By comparison, the Government of Canada's priorities for the Asia Pacific region are available through public documents such as Mandate Letters and annual Departmental Plans. However, GAC management and staff acknowledged that the department's priorities for the region have been dynamic and could change rapidly, making them difficult to align with. The Foundation has expressed a desire for more input from the Government of Canada regarding the need for policy work.

13. There has been no formal mechanism for communication, consultation or coordination between the Foundation and the Government of Canada or Global Affairs Canada.

The Foundation maintained bilateral relations with various funding agencies and departments based on individual contracts. Working level communication lines were well established for contracted programs, such as the APEC-Canada Growing Business Partnership, as well as for specific working relationships such as ABAC and the Canada-China Track II Energy Dialogue. Interviewees reported particularly strong relationships between the Foundation and other government departments and agencies such as ISED and Invest in Canada.

In regard to the management of overall consultations between the Foundation and the Government of Canada, the evaluation found no formal mechanism for communication. Strategic communications surrounding priorities and program development over the past five years were described as ad hoc, transactional and informal. There are currently a number of former GAC employees working for the Foundation or on the Board, which has led to strong relations between the executive levels based on past, professional connections, which in turn has helped to facilitate some consultations and disseminate publications.

Some government stakeholders expressed a desire for better coordination and alignment of priorities. For example, some interviewees expressed concern over the Foundation using its own connections to obtain endorsements for a project before approaching GAC or submitting a proposal. There was also concern over potential duplication of efforts and an overreliance on GAC resources. These concerns have caused tension at times between the department and the Foundation. For example, the Women's Business Mission pilot project in Japan was funded by the Foundation but relied heavily on GAC's Trade Commissioner Service for implementation, requiring mission resources to assist the Foundation, which was not initially planned for by GAC. Additional Virtual Women's Business Missions in South Korea and Taiwan were funded by ISED and had received varying assistance from the Trade Commissioner Service.

The Foundation's senior management and Board have articulated a desire to have a GAC ex-officio member on the Foundation's Board to help improve coordination, collaboration and communication with the Government of Canada. While there are provisions in the Act and the CGA permitting federal public servants to serve on the Board as non-voting members, stakeholders interviewed expressed mixed views. On one hand, there were views that having a GAC representative on the Foundation's Board would improve the department's ability to exercise oversight and report to the Minister. Some felt that it would be beneficial in terms of better understanding the government's priorities. In fact, there was a GAC representative on the Board up until 2016. However, the department has recently decided not to permit a representative to be on the Board due to a potential or perceived conflict of interest. Some interviewees had concerns that the presence of a government representative could indirectly influence Board decisions and not allow an arms-length relationship to be maintained. It should be noted, however, that the department's decision was inconsistent as there are instances of GAC representatives on boards of organizations that are at arms-length and receiving GAC funding, such as the Centre for International Governance Innovation. To help clarify any issues, the department has recently issued an internal directive for assessing participation by employees on the committees and boards of external entities in 2021.

Despite the varying forms of engagement and differing views on communication mechanisms, there was a desire on both parts to improve overall communication and establish clearer roles and responsibilities.

Conclusions

With the arrival of a new President and CEO in 2014, a business model was developed with the Board that moved the organization toward a more action-oriented approach that could serve a larger audience. The Board has done an effective job of governing the Foundation including being actively involved in the changes. The organizational structure now reflects the new approaches being taken including the establishment of a business development team and research staff organized around the new pillars of the Strategic Plan 2019.

During the evaluation period, the Foundation produced solid results that fully align with and were supportive of the CGA outcomes. Its work remains relevant to a broad range of stakeholders including government, business, academia and the general public. The Foundation implemented a series of activities and programs that contributed to increased awareness and understanding of the Asia Pacific region, including education curricula, youth exchanges, National Opinion Polls, Asia Watch, and the Investment Monitor. It has played a positive convenor role through the creation of ABLAC, the secretariat support provided to ABAC and PECC, and the series of women's business missions. These, and other initiatives, have contributed to building networks and ties between Canada and the Asia Pacific region.

With six years of implementation of the business model, a number of trade-offs need to be considered going forward. First, the programming covers a wide variety of areas. Given the inherent limitations of the budget, many stakeholders wondered whether the breadth of the areas being covered was too large for the budget. Second, many of the contracts sourced have been small with a high transaction cost related to their management. On the other hand, while multi-year contracts can provide stable funding, they often require counterpart funding or additional funding from the Endowment revenue. This means that these projects should be strategically selected to ensure they provide a value to the Foundation beyond simply incremental revenue. Third, the CGA requires that 25% of the Endowment revenue generated is used for the grants program. During the period covered by the evaluation, these funds were used primarily for hiring a large number of Post Graduate Research Fellows and Junior Research Fellows. With the grants program embedded in the CGA, changing the staffing model to hire senior researchers and experts was found to be a limitation for the Foundation. However, the Foundation has established a network of Distinguished Fellows, which if fully utilized, could provide a strong pool from which the Foundation could draw expertise and further strengthen its research programming.