Initial Environmental Assessment of the Canada-Indonesia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA)

Table of contents

- Executive summary

- 1. Background and study objectives

- 2. Stakeholder consultations

- 3. Preliminary environmental impact assessment

- 4. Chapter-by-chapter review of enhancement and mitigation options

- 5. Existing environmental legislation, policies and actions

- 6. Conclusion and next steps

- Annexes

- Bibliography

Executive summary

Since 2001, the Government of Canada has conducted environmental assessments of its international trade negotiations, in line with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals. This approach has allowed for the identification of potential environmental impacts of a trade agreement and the identification of ways to mitigate possible negative impacts, either through the course of negotiations or through domestic measures. The purpose of these assessments is to fully integrate environmental considerations into the negotiating process, contribute to informed decision-making, and improve overall policy coherence.

On June 20, 2021, Canada and Indonesia announced that they would begin negotiations on a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA). Both countries recognized the potential for a CEPA to support long-term job creation and economic growth, reduce costs for businesses and consumers, and increase bilateral trade and investment. In line with the Government's commitment to advance an inclusive approach to trade - which recognizes that trade policies need to respond and contribute more meaningfully to overall economic, social and environmental policy priorities - the Government of Canada committed to conduct an expanded impact assessment on the negotiations to include environmental, labour, and gender impacts.

This report presents the Initial Environmental Assessment (IEA) of a possible Canada-Indonesia CEPA. Its purpose is to identify potential impacts on the environment within and outside Canada that may result from a CEPA, assess the significance of these impacts, and identify possible enhancement or mitigation options that may be addressed in the negotiations. The IEA uses Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) economic modelling and environmental data to estimate the potential effects of a Canada-Indonesia CEPA on the Canadian environment. These effects are assessed by first determining how the economies of Canada, Indonesia, and the rest of the world could change as a result of the proposed CEPA, with changes to economic output and consumption behaviour. Then, the impact on the environment is determined by how the new composition of the economies could change greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and the emission of air pollutants.

The modelling reveals that a CEPA with Indonesia is expected to lead to minimal increases in GHG emissions (0.096 Mt CO2e by 2040) and air pollutant emissions by 2040Footnote 1. For both Canada and Indonesia, most of the expected increases in GHG emissions and air pollution are projected to come from the energy sectors, transportation sectors, and sectors that stand to benefit most from tariff liberalization such as electronic products, chemical products, and machinery and equipment. For Indonesia, most of the increases in GHG emissions are projected to come from increased demand for electricity, petroleum and coal products as the Indonesian economy is expected to grow due to a CEPA. Other sectors that could benefit from tariff liberalization, such as textiles, apparel and other manufacturing products are expected to account for the remainder of the increase in GHG emissions. For both Canada and Indonesia, the sectors that are projected to contribute the most to the increase in air pollutants resulting from a CEPA include the transportation and energy sectors.

Recognizing that the modelling approach to environmental impacts is limited in scope and does not capture effects that may not be directly related to changes in output and consumption levels, the study also conducts a qualitative assessment to expand on these environmental indicators and identify other environmental impacts that may result from increased commercial and investment flows between Canada and Indonesia. The qualitative assessment observes the possible environmental concerns and benefits of: GHG emissions, air pollution, deforestation, biodiversity loss, water quantity and quality, marine litter and plastic waste, and managing harmful chemicals.

Based on the results of the model analysis of impacts and the broader review of environmental linkages, the IEA concludes that a Canada-Indonesia CEPA's impacts on the environment are expected to be negligible. Rather, the potential impacts are expected to be limited in extent and scope, and are concentrated in the energy and transportation sectors. Further, the overview of the Government of Canada's existing environmental legislative framework, including statutes, regulations, policies and actions for the prevention and management of environmental risks, suggests that Canada is well positioned to mitigate any potential domestic environmental impacts of an agreement, including through future improvements in the environmental performance of Canadian economic sectors. The CEPA also offers an opportunity to enhance positive impacts or mitigate negative effects from trade through the pursuit of specific outcomes in the agreement. In particular, the chapter-by-chapter review points to several areas for environmental collaboration and risk mitigation, including through environmental provisions, expanded market access for environmentally-friendly products, services and technologies, mechanisms to increase sectoral, technological and institutional cooperation between Canada and Indonesia in key areas, and various investment and government procurement-related provisions.

1. Background and study objectives

In negotiating a CEPA with Indonesia, the Government's objective will be to create new opportunities and meaningful benefits for Canadian business, workers and families, through the elimination of tariffs and a wide variety of non-tariff barriers. In doing so, the Government will seek to ensure that the benefits and opportunities of trade with Indonesia are widely shared, including with traditionally underrepresented groups, such as women and women-owned businesses, Indigenous peoples and Indigenous-owned businesses, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In addition to seeking new commercial opportunities, negotiations will seek to uphold labour rights and standards, ensure that environmental protection is upheld, and prevent parties from lowering environmental standards to promote trade or attract investment, while recognizing that trade policies need to respond and contribute more meaningfully to overall economic, social and environmental policy priorities.

1.1 Economic relationship between Canada and Indonesia

Indonesia is the world's fourth-most populous country with a population of over 275 million and is Southeast Asia's largest economy. With two thirds of its population of working age and a growing middle class, Indonesia is a rapidly emerging country with significant growth potential, including a strong and increasing demand for cereals, wood pulp, and fertilizers. Thus, it is no surprise that Indonesia is Canada's largest export market among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries. In 2019, Canada exported $2.3 billionFootnote 2 in goods and services to Indonesia and imported $1.8 billion in goods and services. Indonesia is also the second-largest destination for Canadian direct investment in Southeast Asia, with a total stock of $3.9 billion in 2019.Footnote 3 There have been consistent levels of investment into Indonesia for the last 20 years.

Canada and Indonesia have enjoyed strong diplomatic relations for over 70 years. The two countries have worked together in many areas, including trade and investment, advancements in human rights, poverty reduction and decentralization of governance.

The proposed CEPA between Canada and Indonesia is intended to benefit businesses through the elimination of tariffs, the liberalization of services and foreign direct investment (FDI), and improved access to public procurement markets. These measures could lead to an array of gains for economic agents in both countries, such as providing a wider selection of products to consumers, lower prices, job growth and enhanced access to South East Asian supply chains.

1.2 Objectives of the proposed Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement

Free trade agreements such as a possible Canada-Indonesia CEPA are binding treaties between countries that open markets for businesses by eliminating or reducing a variety of tariff and non-tariff barriers; establish the terms of market access in areas such as services, investment and government procurement; and set out rules for fair and transparent treatment.

The proposed CEPA aims to address areas beyond the traditional focus of, for example, liberalization of trade in goods and services, investment and government procurement, to also include provisions such as those related to sustainable development, trade and gender, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and trade and Indigenous peoples. For a detailed description of the objectives of each proposed CEPA negotiating area, please refer to Annex A.

1.3 Framework for environmental assessment of trade negotiations

In 2001, pursuant to the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals, the Framework for the Environmental Assessment (EA) of Trade Agreements (the "Framework"), was developed by Global Affairs Canada to evaluate the environmental impacts of Canada's trade policy initiatives.

In 2021, the Framework was renewed to take into account progress on methodologies in conducting EAs and provide updated guidance to trade negotiators to support the continued application of the Directive to future trade negotiations. Based on the principles of flexibility, timeliness, transparency and accountability, evidence-based, and continuous improvement, the objectives of the new Framework are to:

- Assess the environmental risks and opportunities that a potential trade agreement may create within and beyond Canada;

- Assist Canadian negotiators to take into account environmental considerations during the negotiating process, with a view to mitigate risks and enhance benefits and mainstream relevant environmental provisions across the agreement;

- Support the identification of possible additional domestic measures to further mitigate risk and enhance benefits;

- Report to Canadians on how environmental factors are being considered over the course of trade negotiations; and

- Utilize governance structures expected to be established following entry into force of the final agreement to assess and monitor environmental risks identified in the EAs and leverage cooperation activities as well as stakeholder engagement to support mitigation strategies identified during the negotiations.

To ensure that the new Framework is consistent with Canada's inclusive approach to trade, which seeks to ensure that Canada's trade policies more effectively support Canada's economic, social and environmental priorities, and also is consistent with and advances the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy (FSDS), the EA analysis has three complementary components:

- Quantitative and qualitative assessments

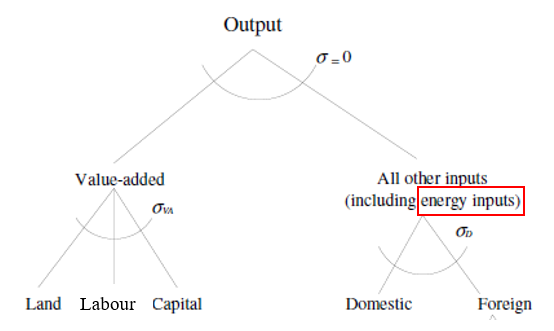

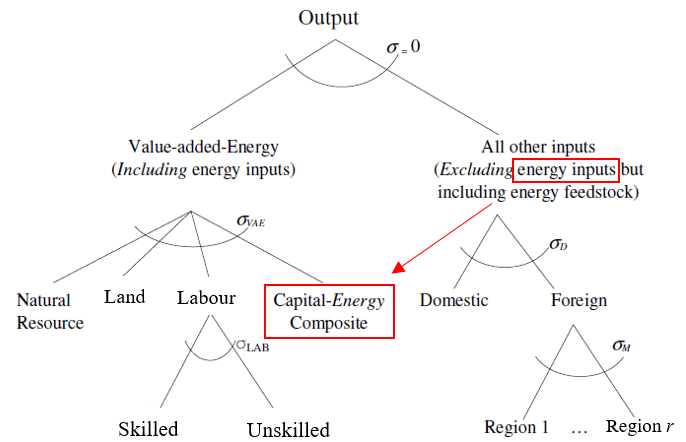

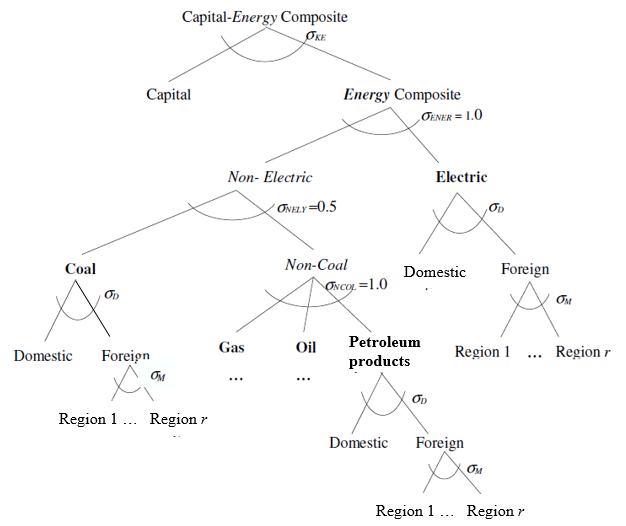

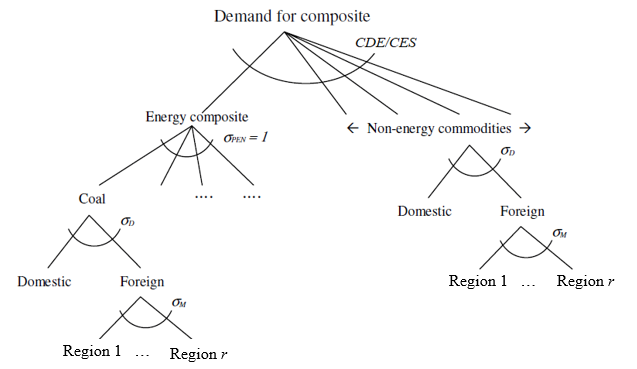

- Quantitative assessment based on the GTAP-e economic model which allows for the comparison of the baseline scenario to the post-liberalization scenario after the agreement's implementation.

- Qualitative assessment and case studies to assess aspects such as impacts outside of Canada or in specific sectors in cases where quantitative data is limited.

- Review of trade agreement provisions

- Generally conducted on a chapter-by-chapter analysis, the review of trade policy aims to provide an opportunity for the trade negotiators to effectively address the findings of the quantitative and qualitative analysis in trade policy to mainstream environmental considerations across the agreement.

- Review of existing environmental legislation, policies, and actions in Canada

- The trade agreement is reviewed in the context of domestic laws, policies and actions to prevent and manage environmental risks in Canada as well as to identify opportunities for additional domestic policy responses.

The EA of trade negotiations benefits from the active support and advice from the following five critical actors: (1) federal departments and agencies, (2) provincial and territorial governments, (3) Indigenous peoples, (4) the Environmental Assessment Advisory Group (EAAG), and (5) the general public.

The Framework follows 4 phases of assessment:

- Initial EA analysis and reporting: the EA process is initiated upon the launch of exploratory discussions and focuses on: (1) activating communication channels with all players of the analysis and (2) establishing the methodological approach and scope of the analysis.

- Integration of environmental considerations: Consolidation of Phase 1 analysis through in-depth quantitative and qualitative measures and integration of environmental considerations into the preparation of Canadian positions. Informal consultations with environmental experts across the government are ongoing throughout negotiations.

- Final EA analysis and reporting: Final EA on the final agreement.

- Monitoring and ex-post reporting: Implementation phase with follow-up and monitoring which may include ex-post environmental studies, ongoing reporting on cooperation activities, and continuous improvement of the EA process through regular consultations and strategic reviews.

2. Stakeholder consultations

In conducting consultations on trade agreements, the Government engages a number of stakeholders and partners, including the public, provincial and territorial governments, Indigenous peoples, Canadian businesses, and civil society organizations, all of which help inform Canada's approach. With respect to the initial EA, the Government also consults with the non-governmental Environmental Assessment Advisory Group (EAAG). The EAAG is made up of persons drawn from the business sector, academia, and non-governmental organizations, and provides advice in its own capacity on the EA undertaken by GAC. At the conclusion of each assessment phase (i.e. Initial, Draft, and Final), EAs are shared with provincial and territorial representatives and the EAAG for feedback before being released for public comment.

Within the Government of Canada, contributions to the environmental assessment comes from a number of federal government departments. This approach facilitates informed policy development and decision-making throughout the negotiations.

This section presents the comments and input that were received from the public, provincial and territorial governments and the EAAG throughout public consultations on a potential Canada-Indonesia CEPA and as a part of the preliminary environmental assessment.

2.1 Consultations – What we heard

Under Global Affairs Canada's revised Environmental Assessment Framework, there is a new commitment to report on the feedback received during public consultations regarding environmental considerations. A Notice of Intent to conduct impact assessments, including an initial environmental assessment on a possible Canada-Indonesia CEPA was published on January 9, 2021, and invited interested parties to submit their views by February 23rd. This process intended to seek the views of all interested Canadians on the potential impacts and opportunities that a Canada-Indonesia CEPA may have with respect to the environment. Although the consultation process has formally closed, the Government will continue to accept submissions.

The Government did not receive any submissions in direct response to the Notice of Intent, however, it did receive valuable input from Canadians related to the environment as part of its broader consultations on a possible Canada-Indonesia CEPA. Out of the total 83 submissions received through this process, 17 submissions mentioned environmental issues. A summary of the feedback received has been published online.

The majority of environmental concerns highlighted by stakeholders focussed on issues related to possible increases in deforestation in Indonesia and carbon emissions. Stakeholders indicated concern with Indonesia's environmental regulations, including the capacity to detect and enforce violations, particularly with respect to sustainable natural resource management. Stakeholders underscored Indonesian sectors that contribute to environmental degradation due to apparel manufacturing, tourism, and palm oil production. Some stakeholders expressed concern that liberalizing trade with Indonesia could result in carbon leakage and a loss in competitiveness for certain Canadian industries due to regulatory incongruity.

Many stakeholders identified commercial opportunities for Canadian companies, particularly as Indonesia is dedicating portions of its post-COVID-19 stimulus funding to sustainable growth. Submissions highlighted opportunities for the clean technology sectors such as renewable energy and waste-management technology, in particular, if ongoing regulatory challenges in the Indonesian market are resolved and improvements are made to its business development environment. Furthermore, certain stakeholders suggested that Canada leverage its low-carbon emission advantage, particularly in sectors such as metals and fertilizer. Stakeholders stressed that the government should maintain a consistent science-based approach to negotiating mutually supportive, robust environment provisions. Stakeholders also indicated that a CEPA could be an opportunity for Canada to work with Indonesia on responsible business conduct (RBC) and environmental policy, share best practices for green growth, and eliminate or reduce barriers for environmental goods and services, and collaborate on waste management, management of harmful chemicals, and international sustainable certification systems.

The Government of Canada received a high-level of engagement from provinces and territories on a possible Canada-Indonesia CEPA throughout the general consultations, including six written submissions that touched on environmental considerations. Provinces indicated that a Canada-Indonesia CEPA should include strong provisions that ensure that trade and environmental protection are mutually supportive and comparable to Canada's existing FTA commitments. Submissions from provinces supported the inclusion in a CEPA of environmental provisions for environmental protection, including those that promote sustainable practices in forestry management, address climate change and conservation of biodiversity, while cautioning against the creation of unnecessary barriers to trade.

2.2 Other consultations

2.2.1 Interdepartmental consultations

Many federal government departments were involved in drafting and reviewing the IEA of a potential Canada-Indonesia CEPA, including Global Affairs Canada; Environment and Climate Change Canada; Employment and Social Development Canada; Natural Resources Canada; Canadian Heritage; Finance Canada; Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada; Canada Border Services Agency; Transport Canada; Fisheries and Oceans Canada; the Public Health Agency of Canada; Health Canada; and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

2.2.2 Environmental Assessment Advisory Group

Members of the EAAG were also engaged in the drafting of the IEA. Given the variety of expertise and approaches represented on the EAAG, the comments received from the group during the initial research phase and drafting phase contributed to the final version of this document. In particular, EAAG members' feedback on the IEA indicated a need to refine the analysis of both countries' government programs for the environment and to elaborate on certain areas of the environmental and clean technology sector.

3. Preliminary environmental impact assessment

The purpose of the IEA is to identify potential impacts on the environment within and outside Canada that may result from a CEPA between Canada and Indonesia and to assess the significance of these impacts. The IEA first uses an integrated trade and environmental model and environmental data to estimate the expected changes to GHG emissions and the emissions of air pollutants as a result of estimated changes in consumption and production under a Canada-Indonesia CEPA.

Recognizing that this modelling approach does not capture other effects that may not be related to changes in output and consumption levels, the analysis also includes the review of other environmental impacts that may result from increased commercial and investment flows between Canada and Indonesia countries (Preliminary Qualitative Assessment). The Government of Canada has further refined its approach to focus on the environmental impact within and outside Canada. Such implications are important to consider in order to provide the level of information and analysis required to contribute to informed decision-making throughout trade negotiations.

3.1 Preliminary economic modelling

Results on the potential economic and trade impact of a Canada-Indonesia CEPA were based on simulations using a dynamic CGE model of global trade. The simulation compares a baseline scenario (prior to implementation of the agreement) to a post-liberalization scenario (following the full implementation of the agreement, by year 2040). The net effect of the agreement is quantified as the difference between the baseline and post-liberalization scenario expressed in terms of changes in GDP, exports and imports.

3.1.1 Limitations of the economic modelling

While the economic modelling analysis is a useful estimation tool, all economic models, by definition, represent a simplification of reality and rely on numerous assumptions. One of these is that the agreement would achieve complete elimination of all agricultural and non-agricultural tariffs between Canada and Indonesia, with no exception made for "sensitive products." Further, the model can reflect only the expansion of trade in products already traded bilaterally (known as the intensive margin of trade). Although the CGE model cannot predict the creation of new trade (or the trade of new products) resulting from a Canada-Indonesia CEPA (known as the extensive margin of trade), the Government has published an expanded economic impact assessment which includes an extensive margin analysis, which aims to enrich the CGE-based analysis by making qualified predictions on possible new trade opportunities resulting from an agreement. However, this extensive margin analysis is independent of the IEA and the resulting export opportunities identified are not factored into the environmental modelling analysis.

3.1.2 Expected impacts on GDP and trade

According to the CGE modelling analysis, the proposed CEPA could boost Canada's real GDP by $328 million (0.012%) by 2040, with the majority of GDP gains coming from increased household consumption and investment. Indonesia could see an increase in GDP by $1.4 billion (0.037%) by 2040.

This analysis projects that Canada's imports from Indonesia could increase by $1.1 billion (47%), primarily driven by imports of apparel and leather products. The increased imports of apparel ($693.9 million) and leather products ($290.4 million) from Indonesia would be offset by reduced imports of the same types of products from other countries such as China, Cambodia and Vietnam. This would limit the impact of the potential agreement on employment in Canada's domestic apparel and leather products industries.

Our projections suggest that Canadian exports to Indonesia could increase by $447 million (7.9%) by 2040, based on the assumption of full trade liberalization, compared to a baseline scenario without liberalization, with the benefits spread over a wide variety of industries, such as food products, chemical products, metal products, computer and electronic products, machinery and equipment and business services.

3.2 Preliminary environmental modelling

Based on estimated changes in GDP and trade presented in section 3.1.2, the preliminary environmental assessment estimates the quantitative environmental impacts of a possible agreement. The analysis also includes a qualitative review of other environmental linkages that may affect the environments within and outside Canada.

3.2.1 Updates to the environmental modelling

The Government of Canada has expanded its existing modelling capacity to incorporate energy-environment-trade linkages within the existing modelling framework (see Annex B for a more detailed explanation of the model). In addition to the typical analysis of GHG emissions, an air pollution database has been integrated into the model to account for possible changes in air quality resulting from a potential agreement.

The new model incorporates carbon emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels and accounts for changes in emissions from fuel substitution. It also incorporates air pollutant data linked with economic activity. For both emissions and air quality, each flow is associated with four possible drivers: output by industries, land and capital used by industries, intermediate input use by industries, and household consumption.

GHG emissions related to energy use include carbon dioxide (CO2) and the non-CO2 greenhouse gases nitrous oxide (N2O), methane (CH4) and fluorinated greenhouse gases (FGAS), which include hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons, sulfur hexafluoride and nitrogen trifluoride. These data are presented in megatonnes (Mt) of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2e).

Emissions related to air quality includes nine substances: black carbon (BC), carbon monoxide (CO), ammonia (NH3), non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOC), nitrogen oxides (NOX), organic carbon (OC), particulate matter 10 (PM10), fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and sulfur dioxide (SO2). This data is presented in gigagrams (Gg).

The base emissions and air quality data for all countries in the world were initially benchmarked to 2014. The data has since been updated to 2019 accounting for changes in economic growth and changes in trade patterns since 2014.

For the purpose of this analysis, complete elimination of all agricultural and non-agricultural tariffs between Canada and Indonesia is assumed, with no exception made for "sensitive products"—notwithstanding that trade and investment liberalization initiatives often contain provisions that exempt certain sectors from liberalization or restrict the applicable extent of liberalization.

3.2.2 Limitations of the environmental modelling

Calculations of changes in GHG emissions and air pollution are based on projected GDP and trade impacts, as measured by the economic simulation. Consequently, they inherit the same limitations as the economic modelling.

In addition, there are cautionary notes specific to the interpretation of environmental modelling results. Notably, projected changes in GHG emissions and air pollution reflect the impacts based on these indicators only, and do not address environmental health effects or capture the breadth of environmental issues that could occur as a result of CEPA. Likewise, this analysis does not take into account any independent events or actions, such as natural disasters, that may adversely affect the environment. This analysis also does not take into account possible technological advances that could reduce emissions of either or both countries in the future. In general, advances in technology are expected to reduce emissions associated with increased economic activity. As a result, it is possible that the figures reported in this analysis overstate the possible impact in the future. Further, this analysis does not reflect future changes to climate or environment-related policies designed to reduce the production of GHG and air pollutant emissions locally and globally.

Furthermore, although the expanded environmental assessment methodology improves upon the previous Environmental Impact Framework, solving some of the prior limitations, it has also moved away from gauging certain environmental variables. For example, the expanded methodology does not take into account key variables such as change in energy usage and water usage. Although the expanded methodology does not take into consideration the change in energy usage by terajoules (TJ), it does include a robust assessment module that uses energy usage as an intermediate input when assessing change in GHG emissions. However, since the expanded methodology does not take into account water usage, the assessment of a possible Canada-Indonesia CEPA's impact on water usage will be further considered in the "Other Linkages" section.

Finally, the projected air pollutant results from the environmental module reflect changes in air pollutants in association with changes in trade and production patterns as a result of a potential CEPA; however, it does not have a mechanism to address capital investment enhancement to mitigate air pollutants. Global Affairs Canada is working to further improve the capacity of this model to more accurately project the association between change in production as a result of a Canada-Indonesia CEPA and the change in air pollutant emissions in Canada and Indonesia.

3.2.3 Impacts on GHG emissions and air pollutants

a. Changes in GHG emissions

Based on the assumption of full tariff liberalization, it is estimated that a potential agreement would have a negligible impact on GHG emissions in both Canada and Indonesia. This result is expected as the trade agreement is expected to have a modest impact on the economies of Canada and Indonesia.

Table 1: Projected Change in Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Canada by 2040, resulting from the potential agreement, Mt CO2e

| Change | Proportion of Total | |

|---|---|---|

| CO2 | ||

| CO2 | 0.063 | 66.2% |

| Non-CO2 | ||

| N2O | 0.004 | 4.2% |

| CH4 | 0.012 | 12.0% |

| FGAS | 0.017 | 17.7% |

| Total | 0.096 | 100% |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist

Source: Office of the Chief Economist

In Canada, GHG emissions would be expected to increase by 0.096 Mt CO2e by 2040 as a result of increased economic activity resulting from the potential agreement, representing an increase of less than 0.01% compared to the base level of GHG emissions for Canada projected to be 1,092 Mt CO2e in 2040. This baseline is based on current activity and absent any environment or climate-related policies intended to reduce GHG emissions.Footnote 4 Roughly two-thirds of the increased emissions are expected to come from CO2 directly.

Table 2: Change in Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Indonesia by 2040, resulting from the potential agreement, Mt CO2e

| Change | Proportion of Total | |

|---|---|---|

| CO2 | ||

| CO2 | 0.802 | 81.0% |

| Non-CO2 | ||

| N2O | 0.024 | 2.4% |

| CH4 | 0.172 | 17.4% |

| FGAS | -0.008 | -0.9% |

| Total | 0.990 | 100% |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist

Source: Office of the Chief Economist

In Indonesia, GHG could increase by 0.99 Mt CO2e by 2040, or 0.04%, compared to the projected base emissions of 2,451 Mt CO2e in 2040. Approximately 81% of this increase would be due to direct CO2 emissions, while the majority of the remainder would stem from increased methane emissions.

Table 3: Change in Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Source by 2040, resulting from the potential agreement, Mt CO2e

| Canada | Indonesia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | Proportion | Change | Proportion | |

| Production | 0.084 | 87.8% | 0.835 | 84.4% |

| Consumption | 0.012 | 12.2% | 0.155 | 15.6% |

| Total | 0.096 | 100% | 0.990 | 100% |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist

Source: Office of the Chief Economist

For both Canada and Indonesia, increased production resulting from the potential free trade agreement would account for the majority of the increase in GHG emissions. The increase in production would account for as much as 87.8% of the increased GHG emissions in Canada's case and 84.4% in Indonesia's case.

Table 4: Change in Carbon Dioxide Emissions vs. Non-CO2 Emissions by Source by 2040, resulting from the potential agreement, Mt CO2e

Change in CO2 Emissions

| Canada | Indonesia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | Proportion | Change | Proportion | |

| Production | 0.052 | 81.9% | 0.650 | 81.0% |

| Consumption | 0.011 | 18.1% | 0.153 | 19.0% |

| Total CO2 | 0.063 | 100% | 0.803 | 100% |

Change in Non-CO2 Emissions

| Canada | Indonesia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | Proportion | Change | Proportion | |

| Production | 0.032 | 99.2% | 0.186 | 98.8% |

| Consumption | 0.000 | 0.8% | 0.002 | 1.2% |

| Total Non-CO2 | 0.032 | 100% | 0.188 | 100% |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist

Source: Office of the Chief Economist

This split between production and consumption holds when considering carbon dioxide emissions only, as can be seen in Table 4. However, non-CO2 emissions are driven almost entirely by changes in production and not consumption. It should be noted that the analysis presented in this study captures not only changes in GHG emissions in the sectors directly affected by the CEPA, but also changes in GHG emissions resulting from the expansion of economic activities in production and consumption resulting from the CEPA. Overall, as demonstrated in table 4, the majority of CO2 and non-CO2 emissions are generated by the production within these sectors rather than the consumption (i.e., the end use) of these products.

Table 5: Top 10 Sectors in Canada Contributing to Change in Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2040, resulting from the potential agreement, Mt CO2e

| Sector | Change | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Land and pipeline transport | 0.019 | 19.5% |

| Petroleum, coal products | 0.014 | 14.9% |

| Computer, electronic and optical products | 0.012 | 12.4% |

| Chemical products | 0.006 | 6.2% |

| Gas | 0.006 | 6.2% |

| Water | 0.005 | 5.0% |

| Air transport | 0.004 | 4.6% |

| Machinery and equipment | 0.004 | 4.1% |

| Cereal grains | 0.004 | 4.0% |

| Water transport | 0.004 | 3.9% |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist

Source: Office of the Chief Economist

When it comes to the sectors that would contribute the most to the increase in GHG emissions resulting from a potential free trade agreement, in Canada, there are three sectors that make up almost half of the expected increase: land and pipeline transport; petroleum and coal products; and computer, electronic and optical products.Footnote 5 As can be seen in Table 5, the sectors that are expected to contribute the most to increased GHG emissions in Canada would be energy sectors as well as sectors that are expected to benefit the most from a trade agreement with Indonesia. These sectors include electronic products, chemical products, machinery and equipment and cereal grains. Together, the top 10 sectors account for 81% of the expected increase in GHG emissions in Canada.

Table 6: Top 10 Sectors in Indonesia Contributing to Change in Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2040, resulting from the potential agreement, Mt CO2e

| Sector | Change | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 0.389 | 39.3% |

| Petroleum, coal products | 0.189 | 19.1% |

| Water transport | 0.098 | 9.9% |

| Mineral products | 0.059 | 6.0% |

| Land and pipeline transport | 0.051 | 5.2% |

| Textiles | 0.044 | 4.5% |

| Wearing apparel | 0.041 | 4.1% |

| Trade | 0.031 | 3.1% |

| Other manufacturing | 0.030 | 3.0% |

| Construction | 0.017 | 1.8% |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist

Source: Office of the Chief Economist

In Indonesia, almost 60% of the expected increase in GHG emissions would be due to electricity, petroleum and coal products. Other sectors that would contribute to the increase in GHG emissions would be water and land and pipeline transport industries, in addition to industries that would be expected to benefit the most from tariff liberalization. These industries include mineral products, textiles and apparel, other manufacturing, and some services sectors. The top 10 sectors account for 96% of the increase in GHG emissions in Indonesia.

b. Change in Air Pollutant Emissions

It is expected that the proposed agreement would have a minimal impact on air quality in both Canada and Indonesia.

Table 7: Change in Air Pollutant Emissions in Canada by 2040, resulting from the potential agreement, Gg

| Change | Proportion | |

|---|---|---|

| BC | 0.007 | 0.4% |

| CO | 0.800 | 45.2% |

| NH3 | 0.077 | 4.4% |

| NMVOC | 0.211 | 11.9% |

| NOX | 0.390 | 22.1% |

| OC | 0.007 | 0.4% |

| PM10 | 0.058 | 3.3% |

| PM2.5 | 0.053 | 3.0% |

| SO2 | 0.164 | 9.3% |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist

Source: Office of the Chief Economist

In Canada, almost half of the air pollutant increase is expected to be from increased carbon monoxide emissions, while another approximately 40% would be explained by increases in emitted air pollutants, including from emitting nitrogen oxides (NOx), non-methane volatile organic compounds (MNVOCs) and sulfur dioxide (SO2).

Table 8: Change in Air Pollutant Emissions in Indonesia by 2040, resulting from the potential agreement, Gg

| Change | Proportion | |

|---|---|---|

| BC | 0.345 | 0.4% |

| CO | 59.045 | 70.9% |

| NH3 | 0.905 | 1.1% |

| NMVOC | 8.472 | 10.2% |

| NOX | 5.521 | 6.6% |

| OC | 0.838 | 1.0% |

| PM10 | 4.264 | 5.1% |

| PM2.5 | -0.293 | -0.4% |

| SO2 | 4.211 | 5.1% |

| Total | 83.309 | 100% |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist

Source: Office of the Chief Economist

In Indonesia, over 70% of the air pollutant emissions increase is expected to be due to increased carbon monoxide emissions, with an additional 10% resulting from non-methane volatile organic compounds.

Table 9: Top 10 Sectors in Canada Contributing to Change in Air Pollutant Emissions by 2040, resulting from the potential agreement, Gg

| Sector | Change | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Land and pipeline transport | 0.478 | 27.1% |

| Petroleum, coal products | 0.380 | 21.5% |

| Water transport | 0.340 | 19.3% |

| Ferrous metals | 0.126 | 7.2% |

| Cereal grains | 0.090 | 5.1% |

| Chemical products | 0.078 | 4.4% |

| Machinery and equipment | 0.042 | 2.4% |

| Vegetables, fruit, nuts | 0.040 | 2.3% |

| Electricity | 0.031 | 1.7% |

| Business services | 0.029 | 1.6% |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist

Source: Office of the Chief Economist

In terms of the sectors that would contribute the most to the anticipated increase in air pollutant emissions resulting from a potential free trade agreement in Canada, almost 70% of the increase would be explained by increased activity in land transport, petroleum and coal products, and water transport. In addition to the energy and transportation sectors, other sectors that would contribute the most to increased air pollutants in Canada are expected to be ferrous metals, cereal grains, chemical products, raw milk, machinery and equipment, and vegetables, fruits and nuts. Together, the top 10 sectors account for 92.6% of the expected increase in air pollutants.

Table 10: Top 10 Sectors in Indonesia Contributing to Change in Air Pollutants by 2040, resulting from the potential agreement, Gg

| Sector | Change | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Petroleum, coal products | 49.744 | 59.7% |

| Land and pipeline transport | 8.754 | 10.5% |

| Electricity | 5.189 | 6.2% |

| Trade | 4.021 | 4.8% |

| Other manufacturing | 3.830 | 4.6% |

| Textiles | 2.813 | 3.4% |

| Wearing apparel | 2.541 | 3.1% |

| Mineral products | 1.956 | 2.3% |

| Accommodation, Food and Service activities | 1.708 | 2.1% |

| Public Administration and Defense | 1.640 | 2.0% |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist

Source: Office of the Chief Economist

In Indonesia, almost 60% of the increase in air pollutants would be derived from the petroleum and coal products sector alone. An additional 10.5% of the increase in air pollutants in Indonesia would be from increased land and pipeline transport activity. Other sectors that would be expected to contribute to increases in air pollutants would be some sectors that are expected to benefit from the potential agreement including other manufacturing, textiles and apparel, mineral products and some services sectors. In total, the top 10 sectors would account for 98.7% of the expected increase in air pollutants in Indonesia.

c. Modelling Conclusions

Based on the above results, which included modelling the effect of removing trade barriers between Canada and Indonesia, and enhancing economic cooperation between the two countries is desirable; a potential CEPA would generate economic benefits for both economies while having a minimal effect on the environment for both parties.

Although the expected change in GHG emissions in both Canada and Indonesia are insignificant in absolute terms, it is evident that Indonesia is expected to experience a disproportionately higher change in GHG emissions and air pollution relative to Canada. This analysis projects that Indonesia's change in GHG emissions (0.99 Mt) would be approximately ten times higher than that of Canada (0.096Mt), notwithstanding Indonesia's projected increase in exports ($1.1B) is only 2.5 times higher than that of Canada ($446.5M). Indonesia is projected to emit four times more GHG emissions than Canada per dollar increase in exports as a result of a Canada-Indonesia CEPA.

Similarly, Indonesia is expected to experience a disproportionately higher change in air pollutant emissions relative to Canada. This analysis projected that Indonesia's change in air pollutants (83.3 Gg) would be approximately forty-seven times higher than that of Canada (1.77 Gg). Indonesia's emissions of air pollutants are projected to be almost 19 times higher than Canada's per dollar increase in exports as a result of a Canada-Indonesia CEPA. Given that air quality in Canada is generally better than that of Indonesia, these emissions could be expected to add to the burden of exposure already being experienced in the country. The impact to Canada's air quality is likely to be significantly less, particularly considering Canada's significant land mass and lower population density in comparison to Indonesia.

While significant in relative terms, projected increases in GHG emissions and air pollution are limited in absolute terms and expected to be spread over a long period of time (by year 2040). This report will seek to identify some of the possible measures than can be achieved through negotiations, or exist domestically, that could potentially mitigate this outcome.

3.3 Preliminary qualitative assessments

The potential environmental impacts of a CEPA between Canada and Indonesia extend beyond those captured by the environmental indicators above. In order to capture a broad view, it is necessary to expand the analysis beyond the economic and environmental modelling, to scan other potential environmental impacts that may result from increased commercial and investment flows between Canada and Indonesia.

This section is intended to provide an overview of some of the additional risks and benefits that are not captured in the previous modelling. This analysis provides more qualitative analysis of the possible effects of GHG emissions and air pollutants by observing the linkages of a possible CEPA and climate change and transboundary air pollution. Beyond expanding on these environmental indicators, the qualitative assessment extends to other areas of possible environmental concerns and benefits, including deforestation, biodiversity loss, water quantity and quality, marine litter and plastic waste, and managing harmful chemicals.

3.3.1 Greenhouse gas emissions

As illustrated in the quantitative analysis above, an increase in international trade as a result of a CEPA between Canada and Indonesia is likely to be associated with growth in production and consumption of goods and services and an increase in foreign direct investment abroad that are associated with or contribute directly to changes (both increases or decreases) of GHG emissions.

An increase of trade and investment could also contribute to higher activity in the international shipping industry, which accounts for a significant amount of global GHG emissions. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 90% of the world's merchandise trade travels by sea, which represented 10.7 billion tonnes of goods moved in 2018. Taking into account the geographical location of Canada and Indonesia, the additional trade flows generated by a CEPA are likely to translate into more intensive use of maritime transportation.

Although the domestic fossil fuel industry is likely to continue production (particularly the Canadian Oil Sands), Canada is on track to exceed its previous Paris Agreement GHG emissions reduction target of 30% below 2005 levels by 2030 and has committed to an enhanced 2030 reduction target of 40-45% below 2005 levels. Canada's economy has grown more rapidly than its GHG emissions, with emissions intensity declining by 36% since 1990 and 20% since 2005. This decline can be attributed to the decrease in carbon emissions by electricity and heavy industry, and declining emissions intensities from oil and gas operations, which have offset the increases in absolute emissions from the oil and gas and transportation sectors. Similarly, technological and operational efficiency improvements have resulted in a reduction in oil sands emissions intensity of 36% from 2000 to 2018Footnote 6. In addition, oil sands producers recycle about 75% of water used in oil sands mining and 86% of the water used for in-situ production. The impact of a Canada-Indonesia CEPA on Canada's heavy industry emissions is expected to be minimal. Increased international trade would also generate revenue that could lead to funding to deploy decarbonisation technologies and support innovations to further mitigate carbon emissions in Canada.

Furthermore, the Government of Canada actively maintains mitigation measures, particularly for the agriculture and agri-food sector, such as funding to support the implementation of on-farm actions in the form of Beneficial Management Practices (BMPs). Many mining companies have made bold Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG) commitments including reduction in GHG emissions. Increased sales will provide increased revenue that could facilitate the adoption of new technologies and processes to reduce GHGs, especially in the agricultural and agri-food sector where Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) and provincial governments are already working with farmers and processors to reduce their emissions.

3.3.2 Air pollution

As illustrated in the quantitative analysis, an expected increase in air pollutant emissions within certain industries could be attributed to an increase in international trade resulting from a CEPA between Canada and Indonesia. Anthropogenic sources of transboundary air pollution include emissions from transportation, energy production and use, heavy industry, and from the burning of forests for agricultural needs. Transboundary air pollution is an ongoing concern as the world's factories and agro-forestry projects grow and cluster in manufacturing and resource-intensive regions, including in both Canada and Indonesia. The quantitative analysis reveals that although the majority of Canada and Indonesia's increases in air pollutant emissions as a result of a CEPA is expected to come from some of these sectors, their impact will be minimal.

While the environmental modelling presented in the previous section captures emissions originating from Canadian-owned and Indonesian-owned transportation service providers, it does not include emissions originating from intermediary foreign service providers. An increase of trade and investment could also contribute to higher activity in the international shipping industry, which is a significant source of pollution. The transportation sector is also responsible for the emission of air pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, sulphur oxides, volatile organic compounds and particulate matter.

Any impact would be marginal in Canada due to the implementation of policies that seek to mitigate transboundary air pollution. In Canada, addressing air pollution is a shared responsibility among federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal governments. The federal government collaborates with provincial and territorial governments to implement Canada's Air Quality Management System (AQMS), which includes Canadian Ambient Air Quality Standards (CAAQS), industrial emissions requirements, provincial air zones and interprovincial airsheds, as well as reporting to Canadians. In addition, the federal government has put in place a number of regulatory and non-regulatory measures to address air pollutant emissions from industrial sources, as well as from transportation sources and consumer and commercial products.

Through its domestic actions to meet commitments under the Canada-U.S. Air Quality Agreement, Canada has made significant progress domestically to reduce emissions of sulphur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), which cause acid rain and emissions of NOx and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that form ground-level ozone, key components of smog. All of these pollutants negatively affect human health. Canada's total SO2 emissions decreased by 69 percent between 1990 and 2017, and Canada's total NOx emissions decreased by 59 percent between 2000 and 2017 in the area covered by the Agreement.

3.3.3 Deforestation

DeforestationFootnote 7 is a significant environmental issue due to its linkages to loss of biodiversity, reduced soil and water quality, habitat degradation, and climate change. Deforestation is often a direct result of unsustainable industrial activity (i.e., logging, agriculture, mining, energy development and production, and infrastructure development), which can be associated with increases in international trade and investment.

Canada has one of the lowest deforestation rates in the world (0.02%). According to laws, regulations and policies in place across Canada, all areas harvested on public land must be reforested, either by replanting or through natural regeneration. About 94% of Canada's forests are on public land, predominantly provincial. The increase in trade and investment with Indonesia in specific products and sectors (e.g. mining) could contribute directly to deforestation. In the case that a CEPA leads to an increase in mining activity, any new mining projects would be subject to the Impact Assessment Act, which would require proper consideration of environmental risks, including deforestation. Provinces and territories also have their own legislative and regulatory frameworks for environmental assessments and approvals for projects under their constitutional jurisdiction.

Canada could potentially risk contributing to deforestation in Indonesia, due to a possible increase in consumption of imported palm oil and rubber products. From 2017 to 2019, Canada imported an annual average of CA$51.1M worth of palm oil from Indonesia. The production of palm oil in Indonesia is driven by global demand and from 2017-2019 Canada imports only accounted for 0.2% of Indonesia's total annual global exports of the product (2017-2019 average). Virtually all of Canada's palm oil imports from Indonesia are refined, which enter the country tariff-free. Canada currently applies a tariff of up to 6% on imports of crude palm oil from Indonesia, which Indonesia may seek to reduce or eliminate through negotiations of a CEPA. However, Canada does not generally import crude palm oil. Given that the existing tariff is already relatively low, its reduction or elimination is unlikely to alone significantly increase its importation of crude palm oil. Any increase of palm oil from Indonesia would likely be the result of import substitution from other major exporters such as Malaysia.

A CEPA is not likely to have a significant effect on Indonesian palm oil production given that Canada is a minor importer of this commodity in terms of both its global share and absolute value of imports. However, during the negotiations Canada could seek opportunities to help de-link palm oil and other agricultural production from deforestation through strengthened policy dialogue and government-to-government collaboration. Lastly, there is growing momentum in multilateral fora (such as the OECD, and the G7) toward deforestation free supply chains, which could lead to a further shift away from unsustainable palm oil production.

3.3.4 Biodiversity loss

Both Canada and Indonesia rely on the biodiversity of their ecosystems to maintain their access to domestic ecological goods and services (EG&S), on which their economies rely. Although Canada and Indonesia face different pressures, as is the case globally, similar factors contribute to biodiversity loss in both countries. These include habitat degradation and fragmentation, landscape and land-use changes, overexploitation, illegal fishing, illegal logging, illegal wildlife trade, pollution, climate change, and invasive alien species.

In Canada, responsibility for conserving biodiversity and ensuring the sustainable use of biological resources is shared between all levels of government. Although Canada has implemented a number of laws and policies to mitigate loss of biodiversity, populations of species at risk continue to decrease. Loss of biodiversity in Canada continues to be driven by the cascading effects of habitat loss, climate change, pollution, invasive alien species, and in some cases unsustainable natural resource management. As a result, Canada continues to monitor the harvesting and trade of, for example, fish and seafood in order to maintain biodiversity and sustainable harvest levels, and prevent the overexploitation of resources. However, according to the quantitative analysis presented in this study, these sectors are not expected to be affected by a Canada-Indonesia CEPA to a degree where there would be significant environmental impact in this area.

The trade of wildlife is also a contributing factor to biodiversity loss. Canada is party to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which is a treaty protecting wild plants or animals from the threat of international trade. However, pressures on wild populations of species in other countries can lead to decimation, which, in turn, can lead to the poaching and illegal trade of Canadian species, such as turtles, black bear and eels.

3.3.5 Water quantity and quality

International trade and the expansion of industry can have negative effects on water quantity and water quality. Key drivers in the decrease of water quantity and quality include climate change, infrastructure development, agricultural land use, and water demand for commercial use. Additionally, toxic industrial waste can contaminate fresh water sources when dumped intentionally or accidentally.

Although Canada is a water-rich country with a supply far exceeding the population, its fresh water sources are not evenly distributed and there are regional water quantity and water quality issues. About 60% of fresh water in Canada flows to the north, away from the majority of the population. Because northern communities – both Indigenous and non-Indigenous – are often downstream, they are particularly affected by water issues. Flooding and drought can lead to negative economic impacts such as crop failure and damage to infrastructure (i.e., roads, bridges and buildings). Additionally, low water levels could impact Canadian seaways (i.e., Great Lakes-St. Lawrence system), which are integral to Canada's participation in international trade.

Increased trade could increase water pollution from sectors such as agriculture (e.g. harmful algal blooms), mining/heavy industry (e.g. waste rock, acidic drainage, leaching of minerals), and forestry (e.g. pulp and paper effluents released into rivers). However, the quantitative analysis above has projected that a CEPA would likely only have a modest impact in these sectors. Industry is a major water user, however, an increase in international trade is not expected to place greater pressure on Canada's fresh water supply. Additionally, international trade would generate revenue that could lead to the adoption of new technologies and innovations to address key fresh water issues, including those related to improving water quality, water use-efficiency, water recycling, and water monitoring.

The Government of Canada has committed to a new Canada Water Agency (CWA) to find the best ways to keep Canada's water safe, clean, and well managed. Throughout 2020 and 2021, the Government of Canada conducted initial discussions and engagement with provinces and territories, Indigenous peoples (ongoing), stakeholders, experts and the public, to inform the development of the CWA. The CWA would work with partners to safeguard freshwater resources for generations to come, including by supporting provinces, territories, and Indigenous partners, in developing and updating river basin and large watershed agreements.

3.3.6 Marine litter and plastic waste

Global plastic production has been increasing over the past several decades at a rate faster than that of any other material. The improper management of plastic waste has led to the contamination of shorelines, surface waters, sediment, soil, groundwater, and local animal life.

Canada has one of the largest coastlines in the world and is a significant consumer of plastic. In Canada, total sales of plastic are estimated at $35 billion (2017), with approximately 4,667kt introduced to the Canadian market in 2016. Plastics are used in a variety of industrial sectors, and demand for plastic products continues to grow. Every year Canadians throw away 3 million tonnes of plastic waste, and only 9% of this waste is recycled, meaning that the vast majority of plastics end up in landfills and 1% finds its way into Canada's natural environment, including as micro-plastics. To address this issue, Canada is implementing a comprehensive approach towards its vision of zero plastic waste by 2030. This includes the implementation of the Oceans Plastics Charter and Canada-Wide Strategy and Action Plan (Phase 1 and 2) on Zero Plastic Waste. According to the analysis presented in this study, an increase in Canada's imports of rubber and plastic products as a result of a Canada-Indonesia CEPA are expected to be limited. However, Canada's imports of textiles and apparel are expected to increase significantly, a sector, which accounts for approximately 6% (267kt) of end-use markets for plastic products in CanadaFootnote 8. With respect to other sectors that stand to benefit, none of these are expected to have a significant impact with respect to plastic waste.

3.3.7 Managing harmful chemicals

Global hazardous chemicals production and use are rapidly increasing, particularly in emerging economies. At the same time, supply chains for products are more globalized and increasingly complex. These represent sources of pollution and exposure to harmful chemicals – from environmental transport through the air, water and migratory species, and imported products from countries that may have less comprehensive or robust chemicals management regimes than that of Canada.

Despite strong domestic actions, Canada remains a recipient of harmful chemicals from international sources and imported products. According to the analysis presented in this study, a Canada-Indonesia CEPA is expected to have a limited effect on Canada's imports of chemical products. Furthermore, any risk to Canadians of exposure to harmful substances would be mitigated by Canada's existing robust laws, regulations, and practices in this area.

Chemicals management is a long-standing core function of the federal government. In Canada, chemicals are notably managed under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, and other federal statutes such as the Fisheries Act, the Pest Control Products Act (PCPA), the Food and Drugs Act (FDA), the Hazardous Products Act (HPA), and the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act (CCPSA), and by the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC). Several provinces also have their own frameworks in place.

Launched in 2006, Canada has a robust Chemicals Management Plan to assess and manage risks from harmful chemicals as defined in Schedule 1 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (e.g. persistent organic pollutants, heavy metals, air pollutants). Thousands of substances have been assessed to identify environmental or health risks, with action taken by Canada on over 500 toxic chemicals. More than 400 risk management measures are in place, such as regulations, pollution prevention plans, public health advice, and voluntary measures.

3.3.8 Indonesia preliminary qualitative assessments

With respect to the environmental impacts of a CEPA for Indonesia from a qualitative perspective, relevant issues are identified below. Our preliminary analysis indicates that a Canada-Indonesia CEPA and the corresponding increase in overall trade activity is not expected to directly or indirectly contribute to the exacerbation of these issues in any significant way. A CEPA would, however, present opportunities to positively contribute to previously existing or expected environmental issues in Indonesia

Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Overall, Indonesia's emissions remain on an upward trajectory. However, Indonesia has a plan to reduce its GHG emissions by at least 29% by 2030, with renewable energy representing 50% of total emission reduction targets from the energy sector and aims to increase the share of renewables in its total energy mix to 23% by 2025.Footnote 9 Indonesia has also introduced a new carbon trading policy to help achieve those objectives.Footnote 10 While Indonesia's energy policies contain elements that support the uptake of renewable energy, the general investment environment currently still favours large-scale, fossil-fuelled power. A CEPA could contribute to a reduction of the environmental footprint of those hard-to-abate sectors in Indonesia through increased trade and investment in clean technologies, such as carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) technologies, and professional services, such as environmental consulting.

Air Pollution: Energy production, heavy industry as well as palm oil production upstream processes are among the main emitting industries in Indonesia. Regulation of air pollution remains complicated due to multiple sources of pollution, including land use, transportation, and industrial activity, which make it difficult to identify specific national sources and implement effective mitigation measures. Similar to GHG emissions, a CEPA could play a positive role in reducing the environmental footprint of certain sectors in Indonesia through increased trade and investment in clean technology products and environmental services that have been developed as part of Canada's efforts to reduce domestic air pollutant emissions.

Deforestation: Indonesia's deforestation rate is estimated at 1.8% per year and the palm oil industry is playing a significant role in this. Direct impacts include an increase in GHG emissions from forest fires as well as the destruction of key peatlands. A CEPA will allow Canada to engage further with Indonesia on this issue, as sustainable forest management provisions are part of Canada's model approach to the environment in its free trade agreements, as is expanded upon in Chapter 4.

Biodiversity Loss: Although Indonesia is a party to CITES, the trade of wildlife is still a contributing factor to biodiversity loss in Indonesia. Indonesia is home to a number of critically endangered species such as the orangutan and Sumatran tiger that are threatened by forest habitat loss. More broadly, the ASEAN region is also a source and consumer of the wildlife trade, including both legal and illegal trade. While biodiversity loss could be associated with an increase in trade if expanded production causes damage to natural ecosystems, a CEPA could also help mitigate these effects through dedicated environmental provisions as highlighted in section 4 of this document.

Water Quantity and Quality: Rapid population growth, an expanding manufacturing sector, insufficient infrastructure, and water privatization issues affect access to potable water and water pollution in Indonesia. A Canada-Indonesia CEPA, especially one that includes investment promotion and protection provisions and which liberalizes trade in services, could further incentivize Canadian environmental and environmentally-related services companies, such as wastewater treatment companies, to enter the Indonesian market and help contribute to the reduction of the environmental impacts related to water quantity and quality issues.

Marine Litter and Plastic Waste: Indonesia is the world's largest archipelagic nation with 70% of the population living in coastal areas and with an ocean economy that generates one quarter of Indonesia's GDP. However, recent estimates suggest that Indonesia faces roughly US$459 million in direct costs to its fishing/aquaculture, shipping, and tourism industries due to marine debris. Similar to the case of Canada, the analysis presented in this study suggests that Indonesia's increase in imports under a CEPA in sectors that would contribute to plastic waste are expected to be very limited. The Government of Canada is also investing in programs to address the global challenges associated with marine litter and plastic waste. For instance, to support the Oceans Plastics Charter adopted on June 9, 2018, Canada made a financial investment of $100 million to support developing countries, including investing $6 million in, and co-chairing, the World Economic Forum Global Plastic Action Partnership (GPAP), which supported the development of Indonesia's National Plastic Action Partnership (NPAP) that aim at achieving a 70% reduction in its marine plastic leakage by 2025.

Managing Harmful Chemicals: Indonesia is a significant producer of chemicals, and under the "Making Indonesia 4.0" initiative, the Government of Indonesia is seeking to grow its chemical industry as one of five priority sectors. This, combined with rapid urbanization in Indonesia, which will rely on construction chemicals (e.g. concrete, coatings), is expected to influence the global market for chemicals. A CEPA with Indonesia, which is expected to increase Canada's exports of chemicals to Indonesia by 4.8%, could present opportunities to Canadian companies active in environmental remediation and green chemicals to offer alternatives to mitigate impacts of the chemical sector in Indonesia.

3.4 Conclusion of the preliminary environmental assessment

As a scoping exercise, this IEA focused on identifying the likelihood of significant positive or negative effects of a Canada-Indonesia CEPA on the Canadian environment. According to the modelling analysis, a CEPA could boost Canada's real GDP by $328 million (0.012%) by 2040 while Indonesia could see a $1.4 billion (0.037%) increase in GDP within the same timeframe. Based on these economic projections, this analysis concluded that GHG emissions are expected to increase by 0.096 Mt CO2e by 2040 in Canada and by 0.99 Mt CO2e in Indonesia, compared to their respective projected baselines. Additionally, air pollutant emissions are expected to increase by 1.77 Gg by 2040 in Canada and by 83.31 Gg in Indonesia compared to their respective projected baselines. Based on these estimates it appears that the net impact of increased production and trade under a CEPA with Indonesia would represent minor increases in aggregate GHG emissions and air pollutants, coming mostly from the transportation sector, energy sector, and sectors that would benefit most from tariff liberalization.

Complementary to this analysis, the qualitative review of other environmental linkages aims to broaden the analysis of potential risks related to a CEPA with Indonesia. While this review does not identify any significant positive or negative impacts on the environment within or outside Canada from such an agreement, it did highlight general environmental concerns related to deforestation, biodiversity loss, water quantity and quality, marine litter and plastic waste, and managing harmful chemicals, which should be considered by the Government of Canada when negotiating a Canada-Indonesia CEPA.

Considering these limited risks, the next sections review the existing environmental legislative framework at the federal level in Canada (Chapter 4), as well as the enhancement and mitigation options that could be considered more specifically in the context of a Canada-Indonesia CEPA (Chapter 5).

4. Chapter-by-chapter review of enhancement and mitigation options

A Canada-Indonesia CEPA could also help to enhance positive impacts and/or mitigate environmental risks, as described in the following section. As the final analytical stage of the environmental impact assessment, this section identifies areas for environmental enhancement and risk mitigation that may be addressed in a potential Canada-Indonesia CEPA. This preliminary analysis aims to respond to the risks identified in section 3, as well as broader environmental considerations, in trade policy terms, with a view to inform ongoing negotiations. For more information on the purpose of each of the negotiating areas mentioned below, please see Annex A.

For the purposes of this report, the assessment has been broken down into five groups of related provisions:

- Environment

- Goods and Services

- Investment

- Government Procurement

- Trade and Indigenous Peoples

Negotiating areas not included in the above groupings are those that are not expected to significantly enhance or mitigate environmental impacts of the agreement.

4.1 Environment

Canada seeks to advance an ambitious, comprehensive and enforceable Environment provisions in all of its FTA negotiations. This includes obligations to ensure that high levels of environmental protection are maintained as trade and investment are liberalized, as well as commitments to address a range of global environmental issues. In addition, Canada includes environment-related provisions in other areas of its FTAs as appropriate, including in the preamble and in the broader initial provisions and general exceptions articles.

In the context of the Canada-Indonesia CEPA, there are opportunities to seek provisions to improve environmental governance and pursue cooperation between the parties and address environmental challenges, not only in relation to the risk areas identified in section 3 of this report but more broadly.

In particular, Canada could use the opportunity of a CEPA with Indonesia to advance four key objectives:

- Strengthen environmental governance by pursuing core obligations to maintain high levels of environmental protection, including commitments to effectively enforce environmental laws, to not derogate from such laws to encourage trade or investment, and to promote transparency, accountability and public participation. In the context of a CEPA with Indonesia, commitments by parties to maintain high levels of environmental protection and improve their respective laws and policies may help mitigate the minor increases expected in GHG emissions and air pollutant emissions identified earlier in this report.

- Support efforts to address a range of global environmental challenges in areas that affect Canada's environment, economy, and health. In addition to potentially helping address specific risk areas identified in section 3 related to GHG emissions, air quality, chemicals management and invasive alien species, environment provisions in a CEPA with Indonesia would provide an opportunity to enhance efforts related to areas such as illegal wildlife trade, resource efficient and circular economy, marine litter and plastic waste, and conservation of biodiversity. An agreement could also include a binding commitment on climate change, which would support broader climate change objectives and align with the 2019–2022 Federal Sustainable Development Strategy (FSDS) goal of promoting substantive climate change provisions in Canada's FTAs. Further, parties could use a CEPA to reaffirm their respective commitments to multilateral environment agreements, and other legal and voluntary and international commitments. Overall, these provisions would support each Party's respective national, bilateral and international commitments to strengthen environmental protection and help advance solutions to current and future global environmental challenges.

- Promote mutually supportive trade and environment objectives through, for example, commitments to promote voluntary best practices of corporate social responsibility and responsible business conduct, voluntary measures to enhance environmental performance, and trade and investment in environmental goods and services. In particular, and subject to a willing partner, such provisions could encourage the promotion of trade in environmental goods and services, including those of particular relevance to the risk areas identified earlier in this report, and to broader climate change mitigation and adaptation goals. Overall, this could also contribute to sustainable growth and the creation of jobs, and would align with the 2019-2022 FSDS goal to grow Canada's clean technology industry and exports.

- Support sustainable management of natural resources by pursuing provisions related to a resource-efficient and circular economy, and sustainable fisheries, agriculture and forest management. Given the importance of natural resources and their significant role in the Canadian and Indonesian economies, these provisions would reinforce the importance of sustainable resource management. These provisions may also help mitigate negative impacts, notably in relation to the agricultural practices highlighted earlier, as well as the generation of waste, illegal logging, overfishing of limited fish stocks, or illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

In addition to the above objectives, Canada's approach to the environment provides an opportunity to build upon existing cooperation activities between Canada and Indonesia on broader environmental issues by establishing a framework for cooperation on matters of mutual interest. Key examples include:

- Since 2004, Canada has been collaborating with Indonesia through the International Model Forest Network (IMFN), a Canadian initiative focused on sustainable forest management and inclusive governance at a landscape scale.

- Canada's $2.65 billion climate finance commitment (running from 2015 to 2021) to support developing countries transition to low-carbon, climate-resilient economies. This includes over $70 million in initiatives benefiting Indonesia. Examples include: The Eastern Indonesia Renewable Energy Project funded through the Canadian Climate Fund for the Private Sector in Asia – Phase 2; the Integrated Disaster Management Project delivered through the Asian Development Bank and; the Sustainable Landscape Climate-Resilient Livelihoods Project delivered by the World Agroforestry Centre (more information available on other initiatives at https://climate-change.canada.ca/finance/). In June 2021, the Government of Canada announced the doubling of its previous climate finance commitment to CAD$5.3 billion over the next five fiscal years. Canada is also a significant contributor to the Green Climate Fund and Global Environment Facility, which also support initiatives underway in Indonesia.

- As a founding member of the Global Plastic Action Partnership, Canada remains actively involved in Indonesia's National Plastics Action Plan. Canada supports activities under Indonesia's Action Plan such as the launch of Indonesia's Financing Roadmap. Canada will provide technical assistance to help unlock financing opportunities as part of the Financing Task Force.

- Canada and Indonesia work closely through two regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs): The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) with a view to using a science-based approach to the sustainable management of Pacific tuna species, in each of these convention areas. We are seeking to negotiate a CEPA with robust fisheries policy and management provisions that would seek to prevent biodiversity loss, and negative impacts on jointly managed fish stocks.

- Under the Forum for International Cooperation on Air Pollution, there are opportunities for Canada and Indonesia to take part in the international exchange of information and mutual learning on both the scientific/technical and policy levels of air pollution. The Forum is a repository for scientific/technical information on air quality and a convenor of countries and organizations with the goal of increased international cooperation on addressing air pollution. Canada intends to participate. While under the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), this forum is not limited to UNECE countries and as such, seeks to broaden cooperation on air pollution beyond the UNECE. Several Asian countries, as well as Latin American countries, have expressed interest in participating.