Minister of International Development - Briefing book

2021-10

A. Key portfolio responsibilities

Strategic overview

Issue

- Poverty and inequality, violence and fragility matter for Canadian stability and prosperity. As such, Canada’s official development assistance (ODA) is an important part of Canada’s wider foreign policy toolkit for engaging and exerting influence in a turbulent world.

- Amid significant and complex shifts to the international development landscape and already record levels of humanitarian needs, Canada and its development partners are focused on addressing the unfolding impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on global poverty, which are expected to be long-lasting, and on efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

- As a respected member of the international donor community, Canada will continue to have opportunities to make a valuable contribution to sustainable development through its international assistance in a manner that reflects its values and interests.

Context

As Minister of International Development, you have lead responsibility for delivering Canada’s international development priorities in a department that brings together Canada’s foreign policy, trade and international assistance capabilities in an integrated way to advance Canada’s interests in the world under the rubric of the government’s broader feminist foreign policy. You will be particularly focused on implementing the Feminist International Assistance Policy so that Canada’s international assistance fosters sustainable development and poverty reduction in developing countries. You are also accountable for Canada’s response to humanitarian crises in developing countries.

Canadian international assistance is guided by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a landmark global agreement that sets out 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and provides the globally-recognized blueprint for pandemic recovery.

The majority of Canadian international assistance is composed of ODA and is subject to Canada’s Official Development Assistance Accountability Act (2008). The act requires that Canadian aid support poverty eradication efforts, consider the perspectives of the poor and be consistent with international human rights standards.

International assistance enables Canada to effect long-term, transformative change abroad that cannot be achieved through other means. Canada’s contributions over the past decades has extended life expectancy, reduced poverty, improved education outcomes, built better government systems and strengthened countries’ resilience to external shocks.

Canada’s international assistance programming includes initiatives to advance peace, security and governance that require close collaboration with the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Canada’s aid also complements the work of the Minister of International Trade, strengthening and stabilizing the economies of low- and middle‑income countries, creating opportunities for mutually beneficial trading partnerships and contributing to wider sharing of trade benefits.

To advance your portfolio, you are supported by the Deputy Minister of International Development and a dedicated team of international assistance experts based in Ottawa and in Canadian embassies around the world.

The international development landscape

The last 18 months have seen Canada’s international assistance policies and programming confront unique challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic has reversed 3 decades of development gains, leading to the first rise in global poverty rates in 2 decades and contributing to the single greatest increase in global hunger recorded to date.

Global Affairs Canada has focused its efforts on fighting the pandemic by strengthening capacities and reinforcing the delivery of health services; stabilizing economies through restored global supply chains and enabling financial stability; and supporting the most vulnerable, both through its humanitarian response and by addressing longer term impacts of the pandemic. The health, economic and social impacts of COVID-19 continue to evolve and will require a long-term, well-coordinated international response.

Canada is collaborating with bilateral, multilateral and Canadian partners to consider the long-term investments required to support a sustainable pandemic recovery. This involves addressing, in particular, vaccine requirements, health systems strengthening, the serious economic setbacks that have contributed to increasing global poverty and inequality, the shadow pandemic related to a rise in gender-based violence, and the unprecedented increase in global hunger and malnutrition. Canada and the wider international community continue to be confronted by complex global issues, such as climate change, humanitarian crises and challenges to human rights, democracy and rule of law that are key constraints to accelerating progress toward achieving the SDGs.

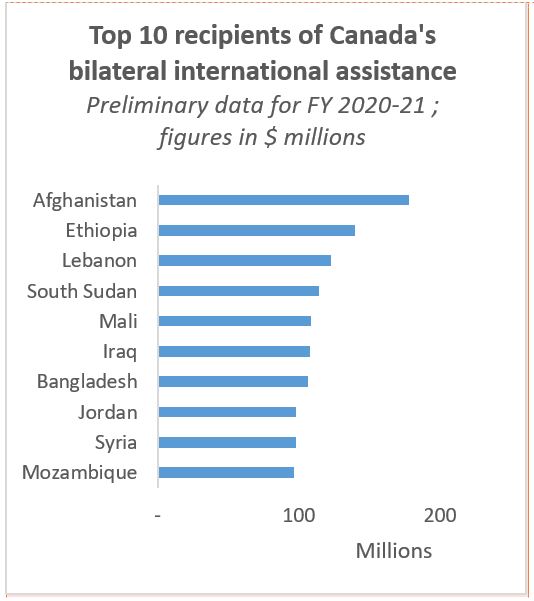

Moreover, fragility, conflict and instability in Afghanistan, Haiti and Ethiopia – among the top recipients of Canadian aid – have highlighted that international development assistance efforts on their own are insufficient to procure stability, peace and prosperity. While development assistance can help create the conditions that lead to stability – for instance, by moving people from poverty to the middle-class, and empowering women and girls to be active leaders in their communities – complex processes of social, political and economic change take time and do not happen in a vacuum.

Indeed, the development community has learned that development efforts must be well-coordinated with humanitarian assistance and peacebuilding activities, and help set in place strong, locally-led institutions and enabling environments to build resilience and safeguard development gains over time.

The global issues that fall under your remit as Minister of International Development are unfolding against a shifting international development landscape where development actors are diversifying and development challenges are increasingly interconnected and complex. There is an increasing competition of ideas around the norms and approaches to delivering international assistance.

In addition to traditional donors and private sector and philanthropic actors, emerging donors are presenting alternative development models. Countries such as China, Brazil and India are investing in international development, bringing their own perspectives and approaches to bear, which are not always aligned with Canada’s values and interests. This increasingly dynamic landscape presents opportunities for Canada to continue to evolve its engagement and forge common ground with a broad spectrum of development partners – donor and recipient countries alike.

Canada's contribution to eradicating global poverty and addressing humanitarian crises

Canada has a long and well-respected tradition of working internationally to help eradicate global poverty. Canada has been an active and engaged international donor since the 1950s. It has earned a reputation for effective collaboration with developing-country partners in Asia, Africa, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, in areas such as gender equality, health and nutrition, education and skills development, humanitarian assistance, and human rights and inclusion.

Canada’s international assistance contributes to global public “goods” (such as reducing carbon emissions, improving food security and addressing health emergencies) that have long-term benefits for Canada and Canadians. International assistance is an important foreign policy tool, helping to strengthen Canada’s relations with bilateral partners and allies and facilitating collaboration with stakeholders in key multilateral forums such as the UN system, the Commonwealth and La Francophonie.

In June 2017, Canada launched its Feminist International Assistance Policy, which outlines what, how and where Canada will deliver its international assistance. The policy seeks to eradicate poverty and build a more peaceful, inclusive and prosperous world. It emphasizes that promoting gender equality and empowering women and girls is the most effective approach to achieve this goal.

Building on Canada’s strong leadership on gender equality since the 1980s, the policy lays out ambitious targets. For example, at least 95% of Canada’s bilateral development assistance should either target or integrate gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls by 2021/22. Concretely, this has meant investments in actions that enhance women and girls’ participation in decision-making, advance their human rights and access to resources, and their ability to fully benefit from development.

Canada is supporting women’s rights organizations and movements around the world and is one of the few donor countries that has committed funding ($100 million over 5 years) to address inequalities in paid and unpaid care work. In 2019/20, Canada reached more than 28.9 million people with projects that helped prevent, respond to and end sexual and gender-based violence; and improved the sexual and reproductive health and rights of over 3 million people, including at least 2.3 million womenFootnote 1.

Investments in health have been crucial to increasing life expectancy and to reducing infant, child and maternal mortality. Canada has been a global thought-leader and investor in health and nutrition for 2 decades. Following on 2 previous global health commitments, in 2019, Canada committed to increase its funding for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health and nutrition around the world to $1.4 billion annually by 2023. Canada has continued its leadership in the health sector throughout the pandemic, committing $2.6 billion in international assistance to the global response to COVID-19. This includes more than $1.3 billion in funding for the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator, through which Canada is supporting the COVAX Facility in the procurement, distribution and delivery of over 165 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines to 86 low- and lower-middle-income countries. The need to give increased attention to future pandemic preparedness can be expected going forward.

Canada’s international assistance also supports education and skills training; promotes inclusive governance and human rights; improves food systems; and addresses environmental and climate change issues – including with its recent commitment of $5.3 billion to support developing country efforts to adapt to and mitigate the impacts of climate change. Canada is also recognized for its leadership and commitment to women, peace and security. For instance, in 2019‑2020, Canada supported 532 civil society organizations, including women’s organizations, to increase participation of women in peace negotiations and conflict prevention.

Canada’s international assistance investments have made an impact over the longer-term in countries where we work. For example, through Canada’s more than $2.38 billion in international assistance to Tanzania since its independence in 1961, significant achievements have been made in health, education and economic growth. In the health sector, Canada’s successful partnership with the Government of Tanzania has contributed to a remarkable 58% reduction in the mortality rate of children under 5 since 2000.

In addition to its investments in long-term sustainable development, Canada has been a significant contributor to global humanitarian action. Canada is seen as an engaged and constructive supporter of the international humanitarian system, and has played a role in developing and/or negotiating key international agreements (e.g. Grand Bargain, Global Compact on Refugees) that seek to strengthen the global humanitarian response to crisis and enhance resilience to shocks. In 2019/20, Canada allocated $872 million in humanitarian assistance, which helped to save or improve the lives of over 98 million people in 60 countries, and respond to 37 natural disasters.

Canada delivers its international assistance in line with internationally agreed development effectiveness principles and promotes innovative approaches, using evidence and experimentation to find solutions to today’s complex development challenges. In the last several years, a number of new mechanisms have been created, including Canada’s development financing institution, FinDev Canada, as well as two new mechanisms that use blended finance and repayable contributions to mobilize and leverage private sector investments in sustainable development (the International Assistance Innovation Program and Sovereign Loans Program).

Canada also works with a range of partners including governments, civil society organizations, international organizations and private sector entities. Your regular engagement with Canadian and international partners will provide opportunities both to shape the international development agenda and advance Canada’s international assistance and foreign policy priorities.

Minister of International Development’s key portfolio responsibilities

Issue

- The Minister of Foreign Affairs has overall responsibility for conducting the external affairs of Canada, including international trade and commerce and international development, as outlined in the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Act (2013).

- In that context, the act further specifies that the Minister of International Development’s role is “to foster sustainable international development and poverty reduction in developing countries and to provide humanitarian assistance during crises.”

Context

International assistance is a key part of how Canada engages with the world and an essential element in our Global Affairs toolkit. As Minister of International Development, your role is to provide specific leadership in overseeing Canada’s development and humanitarian assistance activities as part of a wider team of ministers focused on Canada’s role in a dynamic global context. In 2020‑2021, Canada’s International Assistance Envelope (IAE) totalled over $7.6 billion, although this reflects some extraordinary investments due to COVID-19 Footnote 2.

Supported by the Deputy Minister of International Development, your key responsibilities include:

- Providing strategic direction for policy and programming on international development and humanitarian action, and working closely with other ministers in support of coherent Canadian action across the development-humanitarian- peace and security-trade landscape;

- Managing Canada’s IAE together with the ministers of foreign affairs and finance, including attention to effectiveness and results;

- Reporting on Canada’s international assistance activities and expenses, including via 2 annual reports: the Report to Parliament on the Government of Canada’s International Assistance and the Statistical Report on International Assistance; and

- Providing governance oversight for the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and tabling its annual reports in Parliament.

You will work with ministers, deputy ministers and other senior officials across the department to implement Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy, advance Canadian values of democracy and inclusion, promote development effectiveness and innovation and actively engage with Canadian stakeholders and priority international aid organizations.

You will also work with other Cabinet colleagues to advance joint portfolio responsibilities, such as the Minister for Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) on implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) on the migration file, and the Minister of Finance on international financial institutions (IFIs).

You will attend high-level events and meetings, deliver speeches and make announcements about Canadian aid goals and results. You will also interact with Canada’s international assistance partners in developing countries, and meet with local government officials, members of the development community, civil society organizations and private sector stakeholders. At home, you will play a lead role in engaging Canadians on global issues and in mobilizing their participation in international development initiatives. Through these and other actions, you will help shape Canada’s brand abroad, and strengthen key partnerships.

In carrying out this work, you will be supported by a team of officials with international assistance expertise, based in Ottawa and at Canadian missions abroad.

International Assistance Envelope

The IAE is the Government of Canada’s dedicated pool of resources and main budget planning tool to support international assistance objectives. The IAE funds most of Canada’s official development assistance (ODA) and non-combat security and stabilization activities in support of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

As per its Cabinet-approved management framework, the IAE is co-managed by the ministers of foreign affairs, international development and finance. Alongside your colleagues, you will exercise a leadership role in developing consensus on policy direction for the IAE, in consultation with central agencies. IAE ministers also have specific spending authorities which can be described in conjunction with IAE pools for which they/you are responsible.

Programming Responsibilities

As Minister of International Development, you will play an important role in guiding the allocation of most aspects of Canada’s international assistance funding for programs and specific initiatives, based on Cabinet decisions and government priorities.

Global Affairs Canada follows a rigorous due diligence assessment process when preparing projects. This includes a gender equality plus assessment, which, among other things, rates a project’s level of integration of gender equality and the partner’s capacity in gender‑based analysis. Projects must also be in line with Canada’s Official Development Assistance Accountability Act (2008). The ODAAA requires that, with the exception of humanitarian assistance, projects contribute to poverty reduction, take into account the perspectives of the poor and are consistent with international human rights standards. In accordance with the Impact Assessment Act (2019) and the Cabinet Directive on Strategic Environmental Assessments, all proposed projects are also analysed for environmental risks and opportunities, to ensure they protect the environment and do not result in significant adverse environmental effects. Multilateral, civil society and private sector organizations and governments of international assistance recipient countries are all potential implementing partners of the Government of Canada.

Governorship of development banks

The Minister of International Development is Canada’s governor to the:

- African Development Bank (AfDB);

- Asian Development Bank (ADB);

- Caribbean Development Bank (CDB);

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

These regional IFIs have been established by multiple countries to support international cooperation and help manage the global financial system. For some other IFIs, like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Minister of Finance is the Canadian governor.

IFI programs and projects aim to:

- Reduce poverty;

- Support sustainable economic and social development; and

- Promote regional cooperation and integration, using loans to middle-income countries and through concessional loans and grants to the poorest countries, including fragile states.

As a governor, you are responsible for Canada’s oversight and overall governance of these institutions, including their strategic policy direction, accountability, institutional effectiveness, and financial and programming decisions. Executive directors represent Canada on the boards of directors of these institutions, which are responsible for overseeing their general operations.

International Development Research Centre

The International Development Research Centre (IDRC) is a Crown corporation established by an act of Canada’s Parliament in 1970 (the IDRC Act) with a mandate “to initiate, encourage, support and conduct research into the problems of the developing regions of the world and into the means for applying and adapting scientific, technical and other knowledge to the economic and social advancement of those regions,” with gender equality as a cross-cutting theme.

IDRC is governed by a board of up to 14 governors, whose chairperson reports to Parliament through the Minister of International Development. As per the IDRC Act, you receive the Auditor General’s annual audit report of IDRC, which you then table in Parliament, as part of the centre’s annual report. You are also responsible for tabling the annual report on IDRC’s administration of the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act, and making recommendations on Board of Governors appointments to the Governor-in-Council. On an annual basis, IDRC seeks agreement from the Minister of International Development on the centre’s estimates, and will consult with you on CEO performance agreements and performance evaluation.

FinDev Canada

Canada’s Development Finance Institution (FinDev Canada), launched in February 2018, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Export Development Canada (EDC). FinDev Canada expands Canada’s development finance toolkit by investing in the private sector in developing countries using a gender lens approach to promote economic growth and reduce poverty. Addressing and mitigating the impacts of climate change is also a key priority.

To date, FinDev Canada has signed commitments for 26 investments worth over US$338.3 million (approximately Can$436 million). Starting in 2023-24, FinDev Canada will receive a $300 million recapitalization over 3 years – drawn from EDC’s retained earnings – allowing it to build a portfolio totalling an estimated $1.4 billion.

As per the Export Development Act, the Minister of International Trade is accountable for EDC, but works in consultation with the Minister of International Development on matters related to FinDev Canada’s mandate. As such, you will review and provide advice on FinDev’s strategic priorities, corporate planning and annual reporting, and legislative and regulatory matters.

*See also Department at a Glance.

Ministerial high-level events

November 2021

- 26th Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – Glasgow (Scotland), UK – October 31-November 12

- Co-host SheDecides Champions meeting with 25x25 – Virtual – Early November

- Grand Challenges Annual Meeting – Virtual – November 8-11

- Canadian Conference on Global Health – Virtual/Canada/Ghana – November 24-26

- Canada's Together for Learning Campaign: Made in Canada high-level event – Virtual – November

- Generation Equality Forum (GEF) – Virtual, November

Fall events to be confirmed

- 38e Conférence ministérielle de la Francophonie – Hybrid, location TBD

- UNRWA International Conference – Jordan/Sweden TBC

- Development Ministers Contact Group – Virtual

- Canada-France Conseil ministres – Location TBD

December 2021

- Co-Chair the COVAX AMC Engagement Group Meeting – Virtual – December 6

- Tokyo Nutrition for Growth (N4G) Summit to conclude the Year of Action on Nutrition – Tokyo, Japan – December 7-8

- Global Financing Facility’s 3rd campaign event on the margins of the N4G Summit – Virtual – December 7-8

- Second G7 Foreign and Development Ministers’ Meeting, Liverpool, United Kingdom– December 10-12

- Canada's Together for Learning Campaign: Third ministerial roundtables with the Refugee Education Council (REC) – Virtual – December

PM LEVEL EVENTS

Global Affairs Canada ministers may be asked to participate in the events with the Prime Minister

- North American Leaders’ Summit Meeting – Location TBC - Fall 2021

- ASEAN Leaders’ Summit and related meetings – Virtual, October 26-28

- G20 Leaders’ Summit – Rome, Italy - October 30-31

- Heads of State and Government Summit of the International Coalition for the Sahel – October or November

- COP26 – Scotland, United Kingdom – November 1-12

- APEC Leaders’ Summit – November 11-12

- U.S hosted leaders’ Summit for Democracy – Virtual – December 9-10

B. The department

The department at a glance

Issue

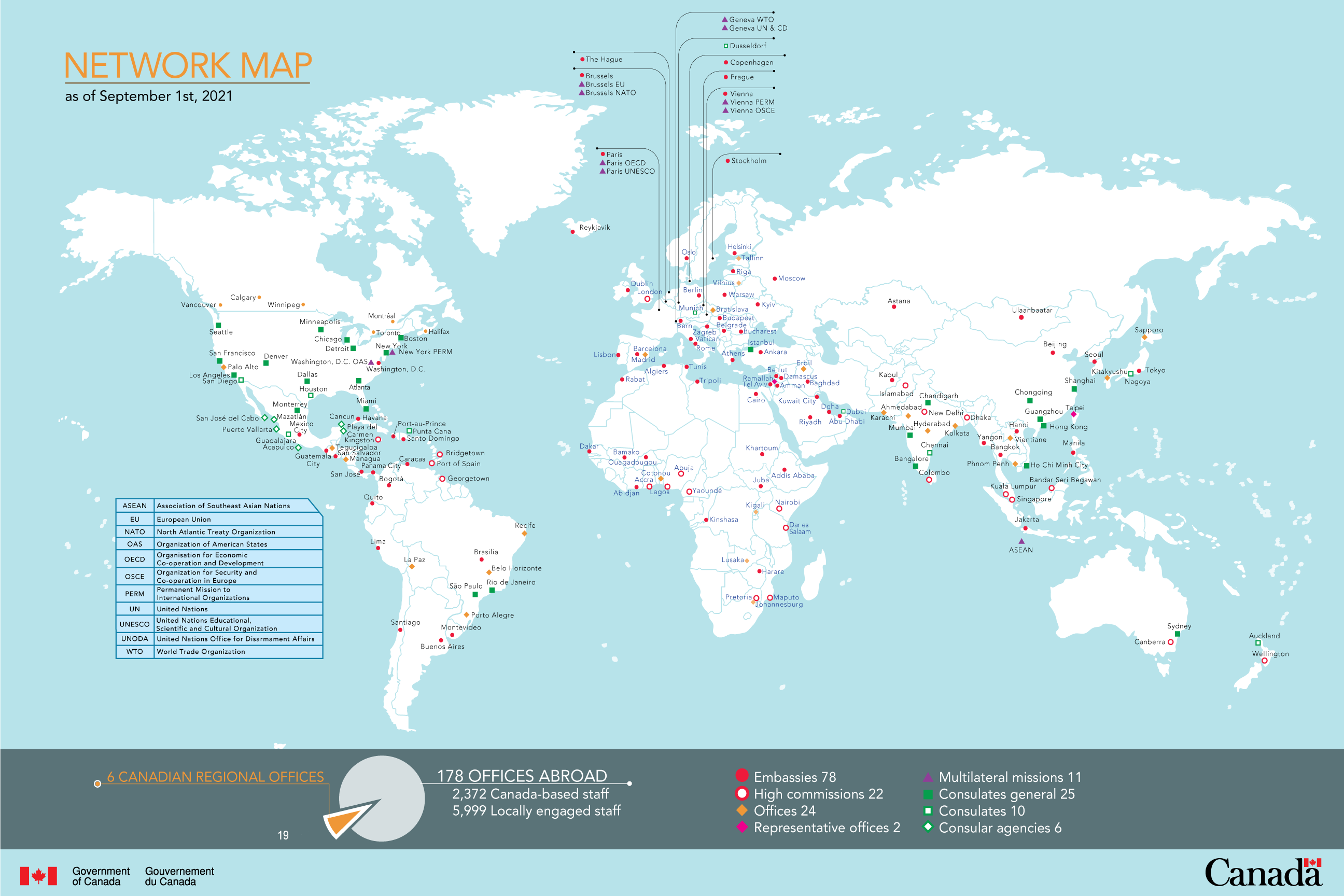

- Global Affairs Canada is responsible for shaping and advancing Canada’s integrated foreign policy, trade and international assistance objectives, and supporting Canadian consular and business interests. We are a networked department with 12,737 employees working in Canada and 110 countries (at 178 missions), with a total budget of $6.7 billion.

Who We Are

Canada’s first foreign ministry was established in June 1909. At punctual moments since then, the department has been renewed to reflect the changing international environment. The most significant adaptations include its amalgamation with the Department of Trade and Commerce in 1982 and with the Canadian International Development Agency in 2013.

While its legal name remains the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (as per the June 2013 act), its public designation under the Federal Identity Program is Global Affairs Canada.

What We Do

The department manages Canada’s diplomatic and consular relations with foreign governments and international organizations, engaging and influencing international players to advance Canadians’ security, prosperity and health in a dynamic global context. It advances a coherent approach to Canada’s political, trade and international assistance goals based on astute and evidence-based analysis, consultation and engagement with other government departments, Canadians and international stakeholders. The department is constantly monitoring global developments and assessing their potential implications on the government’s ability to deliver on its mandate.

The department’s work is focused on five core responsibilities:

- International advocacy and diplomacy: promote Canada’s interests and values through policy development, diplomacy, advocacy and engagement with diverse stakeholders. This includes building and maintaining constructive bilateral and multilateral relationships to Canada’s advantage, primarily through our network of missions; taking diplomatic leadership on select global issues and negotiations; and supporting efforts to build strong international institutions and respect for international law, including through the judicious use of sanctions.

- Trade and investment: support increased trade and investment to raise the standard of living for all Canadians. This includesbuilding and safeguarding an open and inclusive rules‑based global trading system; support for Canadian exporters and innovators in their international business development efforts; negotiation of bilateral, plurilateral and multilateral trade agreements; administration of export and import controls; management of international trade disputes; facilitation and expansion of foreign direct investment; and support to international innovation, science and technology.

- Development, humanitarian assistance, peace and security programming: contribute to reducing poverty and increasing opportunity for people around the world. This includes alleviating suffering in humanitarian crises;

reinforcing opportunities for inclusive, sustainable and equitable economic growth; promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment; improving health and education outcomes; and bolstering peace and security through programs that counter violent extremism and terrorism, support anti-crime capacity building, peace operations and conflict management. - Help for Canadians abroad: provide timely and appropriate travel information and consular services for Canadians abroad, contributing to their safety and security. This includes visits to places of detention; deployment of staff to evacuate Canadians in crisis situations; and provision of emergency documentation.

- Support for Canada’s presence abroad: deliver resources, infrastructure and services to enable a whole-of-government and whole-of-Canada presence abroad. This includes the management of our missions abroad and the implementation of a major duty of care initiative to ensure the protection of Government of Canada personnel, overseas infrastructure and information.

Through these 5 pillars of action, Global Affairs Canada provides an integrated and agile platform from which to deploy and leverage a strong and diverse toolkit, including those skills and assets that come from Canada’s Parliament, other orders of government, the judiciary, Canadian civil society, research institutions and the private sector. These efforts are aligned carefully with government priorities and are amplified through targeted public diplomacy, including on social media.

The department is also supported by a 24/7 Emergency Watch and Response Centre in Ottawa which is always on guard to assist Canadians in need of consular assistance abroad or to respond in real time to natural disasters and complex emergencies around the globe.

Legal responsibilities

The department is the principal source of advice on public international law for the Government of Canada, including international trade and investment law. Global Affairs Canada lawyers develop and manage policy and advice on international legal issues, provide for the interpretation and analysis of international agreements, and advocate on behalf of Canada in international negotiations and litigation. There are also a number of Department of Justice lawyers at the department, who provide legal services under domestic law, including on litigation and regulations such as sanctions implementation.

Our workforce

To deliver on its mandate, the department relies on a workforce that is flexible, competent, diverse and mobile.

The department counts 12,737 active employees; 7,235 of them are Canada‑based staff (CBS), serving either in Canada or at our missions abroad. The remaining 5502 employees are locally engaged staff (LES), usually foreign citizens hired in their own countries to provide support services at our missions. Currently, 56% of CBS are women (compared to 59% of LES) and 59% of the CBS population has English as their first official language (41% French).

A distinctive human resources system allows the department to meet its complex operational needs in a timely manner.

Our staff work in some of the most difficult places on earth, including in active conflict zones. Among the various occupational groups and assignment types, a cadre of rotational employees supports delivery of the department’s unique mandate through assignments typically ranging between 2 to 4-year periods, alternating between missions abroad and headquarters or Canadian regional offices. They are foreign service officers (in trade, political, economic, international assistance, and management and consular officer streams), administrative assistants, computer systems specialists, and executives, including our

heads of mission.

Heads of Mission serve the Minister further to a cabinet appointment. They develop deep expert knowledge of their countries

of accreditation, establish wide networks, and provide advice and guidance on pressing matters of bilateral and international concern. They are responsible for Canada’s “whole of government” engagement in their countries of accreditation and for the supervision of all federal programs present at mission.

Our finances

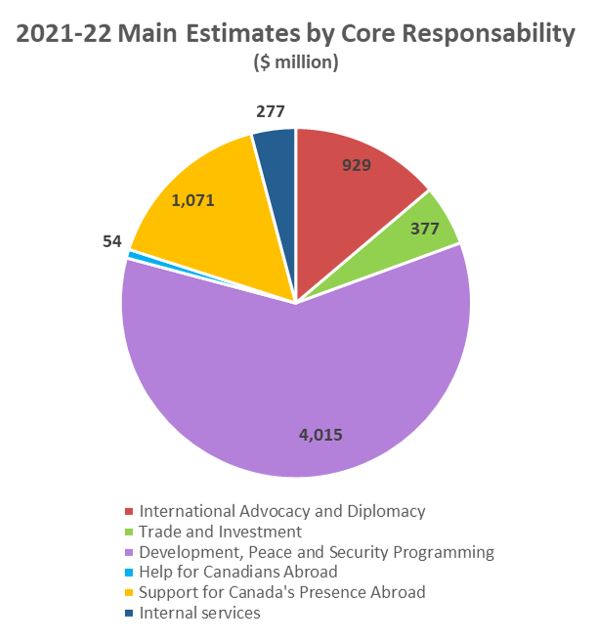

The department’s total funding requested in the 2021-22 main estimates was $6.7 billion. This amount is broken down as follows:

- Vote 1 (Operating): $1,878.2 million

- Vote 5 (Capital): $106.4 million

- Vote 10 (Grants and Contributions): $4,275.9 million

- Vote 15 (LES pension, insurance, social security programs): $85.5 million

- Statutory items (e.g. direct payments

to international financial institutions; contributions to employee benefit plans): $377.3 million.

The budget distribution by core responsibility of the department in the 2021-22 Main Estimates was reported as follows:

Alternative Text

| International Advocacy and Diplomacy | 929 |

| Trade and Investment | 377 |

| Development, Peace and Security Programming | 4015 |

| Help for Canadians Abroad | 54 |

| Support for Canada's Presence Abroad | 1071 |

| Internal Services | 277 |

Chart summarizing 2021-2022 planned spending by core responsibility:

International Advocacy and Diplomacy: $929 million

Trade and Investment: $377 million

Development, Peace and Security Programming: $4015 million

Help for Canadians abroad: $54 million.

Support for Canada’s presence abroad: $1071 million

Internal services: $277 million

Our network

The department’s extensive network abroad counts 178 missions in 110 countries (see attached placemat for an overview of the network). They range in type and status from large embassies, to small representative offices and consulates.

The department’s network of missions abroad also supports the international work of 37 Canadian partner departments, agencies and co-locators (such as Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; National Defence; Canada Border Services Agency; Public Safety; Royal Canadian Mounted Police; Export Development Canada), and provinces and territories.

The department’s headquarters offices are located in the Ottawa-Gatineau region. Most staff are located in the first 3 buildings:

- Lester B. Pearson Building (125 Sussex)

- John G. Diefenbaker Building

(111 Sussex) - Place du Centre (200 Promenade du Portage)

- Queensway Corporate Campus

(4200 Labelle) - Cooperative House (295 Bank)

- National Printing Bureau

(45 Sacré-Coeur) - Fontaine Building (200 Sacré-Coeur)

- Bisson Centre (the Canadian Foreign Service Institute Bisson Campus)

The department also has six Canadian regional officesto engage directly with Canadians, notably Canadian businesses, located in Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montréal and Halifax.

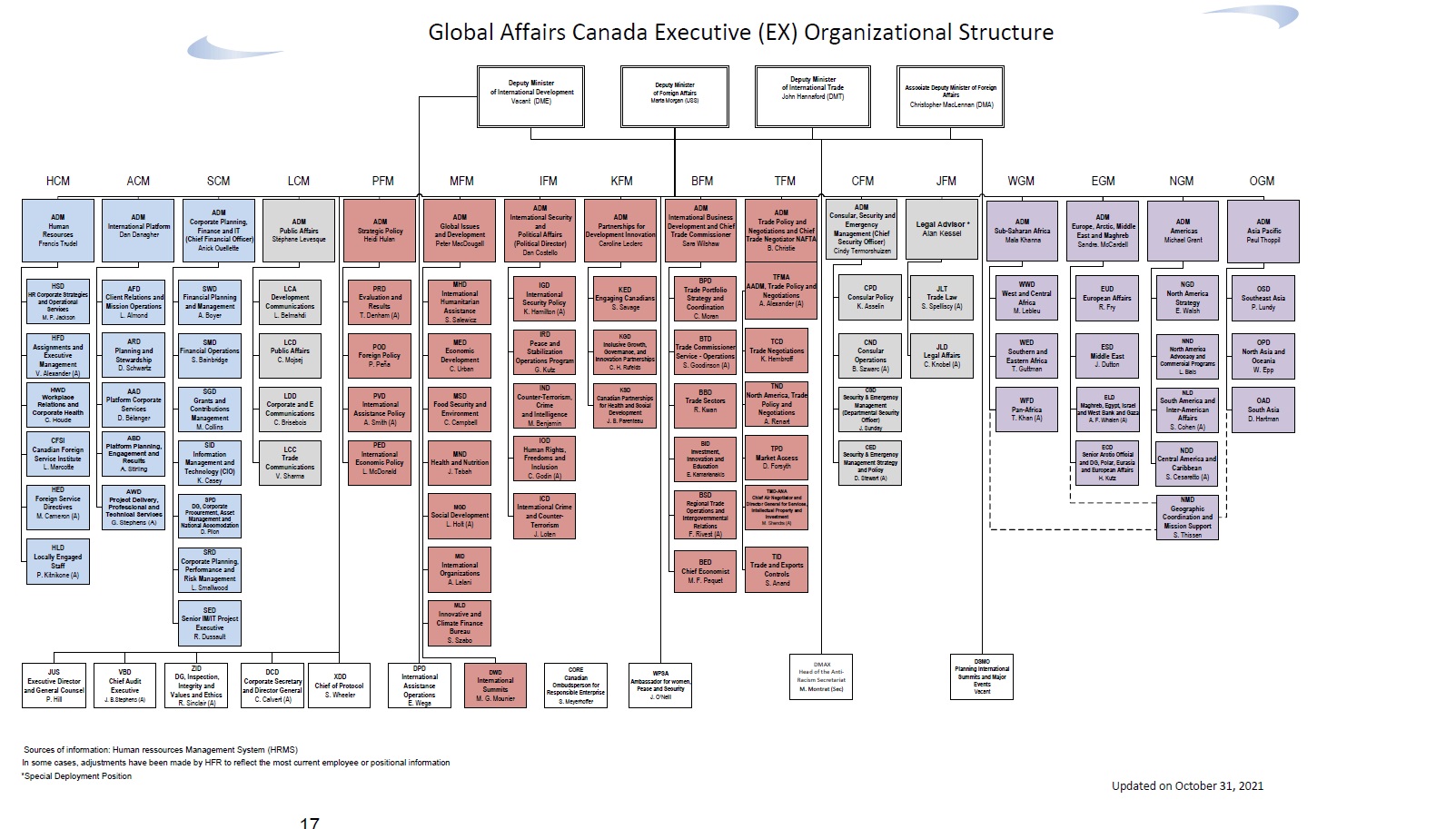

Senior leadership and corporate governance

In support of ministers, the department’s most senior officials are the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs (USS); the Deputy Minister of International Trade (DMT); the Deputy Minister of International Development (DME); and the Associate Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs (DMA). See attached biographies for USS, DMT and DMA.

Sixteen branches, headed by assistant deputy ministers, report to the deputy ministers and are responsible for providing integrated advice across all portfolios, ranging from geographic regions to functional and corporate issues.

The department has a robust corporate governance framework with specific committees for audit, evaluation, security, financial operations, corporate management, policy and programs, and diversity and inclusion. Senior managers from headquarters and the mission network manage and integrate the department’s policies and resources in this context to maximize our assets, and ensure accountability for the delivery of departmental programs and results.

Alternative Text

Chart summarizing 2021-2022 Corporate Governance Committee Structure:

External Committee: Departmental Audit Committee

DM-chaired Committees: Executive Committee; Performance Management and Evaluation Committee

ADM-chaired Committees: Security Committee; Financial & Operations Management Committee; Corporate Management Committee; Policy & Programs Committee; Diversity & Inclusion Council. (All 5 ADM-chaired committees report to the Executive Committee)

Planning and reporting

The department’s annual planning and reporting process is structured around its Departmental Results Framework.

A Departmental Plan establishes the government’s foreign affairs, international trade and development agenda for the coming year. It provides a strategic overview of the policy priorities, planned results and associated resource requirements for the coming fiscal year. The document is approved by the ministers and tabled in Parliament (usually in March/April). The plan also presents the performance targets against which the department will report its final results at the end of the fiscal year through

a Departmental Results Report, typically tabled in Parliament in the fall.

The department’s top corporate priorities are identified each year to ensure that the enabling functions of the department (human resources, finance, IM/IT, accommodations, etc.) are able to provide optimal services to support the department’s mandate. As well, top departmental risks are identified and communicated in the Enterprise Risk Profile. For 2021-22, the department is focusing on mitigating risks related to its workforce (i.e. health, safety and wellbeing of staff, and human resources capacity), IM/IT capacity (i.e. digital transformation and cyber/digital security and resilience), and to the management and security of its real property and assets. Both the corporate priorities and risks are managed through the department’s governance system and re-evaluated on an annual basis.

In the context of COVID-19, there has been an intensified focus on advancing the digital transformation agenda. In particular, the pandemic has highlighted the need for the department to focus on transitioning towards newer digital solutions to enable the nimbleness and effectiveness required to deliver on its mandate and service Canadians. Investments in data driven decision-making, strong collaboration and engagement platforms, and a solid digital foundation will help the department move away from the traditional bricks and mortar and embrace more modern engagement methods to drive diplomacy, trade and international development.

Deputy ministers

Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Marta Morgan

On April 18, 2019, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau appointed Marta Morgan to the position of Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, effective May 6, 2019.

Prior to joining Global Affairs Canada, Ms. Morgan was Deputy Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship for three years. In that role she led the development of immigration policies and programs to support Canada’s economic growth, developed strategies to manage the significant growth in asylum claims and improved client service.

Ms. Morgan has had extensive leadership experience throughout her career in a range of economic policy roles both at Industry Canada and the Department of Finance. She provided leadership in telecommunications policy, spectrum policy, aerospace and automobile sectoral policy, and the development of two federal Budgets.

Ms. Morgan has also held positions at the Forest Products Association of Canada, the Privy Council Office, and Human Resources Development Canada.

Ms. Morgan attended Lester B. Pearson College of the Pacific, she has a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in Economics from McGill University and a Master in Public Policy from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

Deputy Minister of International Trade, John F.G. Hannaford

On December 7, 2018, the Prime Minister appointed John F.G. Hannaford as Deputy Minister of International Trade at Global Affairs Canada, effective January 7, 2019.

From January 2015 to January 2019, Mr. Hannaford was the foreign and defence policy adviser to the Prime Minister and Deputy Minister in the Privy Council Office of the Government of Canada.

Until December 2014, Mr. Hannaford was the assistant secretary to the Cabinet for foreign and defence policy in the Privy Council Office. Prior to December 2011, Mr. Hannaford was Canada’s ambassador to Norway. Before that, for two years, Mr. Hannaford was director general of the Legal Bureau of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. As a member of Canada’s foreign service, he had numerous assignments in Ottawa and at the Canadian embassy in Washington, D.C., during the early years of his career.

Mr. Hannaford graduated from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, with a Bachelor of Arts (First Class) in history. After earning a Master of Science in international relations at the London School of Economics, he completed a Bachelor of Laws at the University of Toronto and was called to the bar in Ontario in 1995.

In addition to his work as a public servant, Mr. Hannaford has been an adjunct professor in both the Faculty of Law and the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa.

Associate Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Christopher MacLennan

On February 7, 2020, the Prime Minister appointed Christopher MacLennan as the Associate Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs. Since May 28, 2021, he has also served as the Personal Representative (Sherpa) to the Prime Minister on the G20. Prior to this, Mr. MacLennan was the Assistant Deputy Minister for Global Issues and Development at Global Affairs Canada. In that role, he led on Canada’s development assistance efforts through multilateral and global partners, humanitarian assistance and priority foreign policy relationships with the United Nations, the Commonwealth and La Francophonie. In addition to this, Mr. MacLennan served concurrently as Canada’s G7 foreign affairs sous-Sherpa.

Previously, Mr. MacLennan was acting Assistant Secretary to the Cabinet for Priorities and Planning and Assistant Deputy Minister of Policy Innovation at the Privy Council Office. Prior to that, Mr. MacLennan was Director General for Health and Nutrition at Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. Mr. MacLennan led the team that organized the Prime Minister’s Saving Every Woman, Every Child Summit on maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) in 2014. This work followed his previous role on the G8 Muskoka Initiative on MNCH in 2010. Prior to this, Mr. MacLennan worked in various capacities at the Canadian International Development Agency, Environment Canada and Human Resources and Skills Development Canada.

Mr. MacLennan holds a Ph.D. from Western University specializing in constitutional development and international human rights and has written numerous publications including Toward the Charter: Canadians and the Demand for a National Bill of Rights, 1929-1960.

Organizational structure

04b - MINA-MINT-MINE - Organizational structure.pdf

Global Affairs Canada Executive (EX) Organizational Structure

Level 1 – Deputy Ministers and Coordinator

Deputy Minister of International Development – Vacant (DME)

Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs – Marta Morgan (USS)

Associate Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs – Christopher MacLennan (DMA)

Deputy Minister of International Trade – John Hannaford (DMT)

Level 2 – Assistant Deputy Ministers and Directors General

Reports to the Deputy Minister of International Development:

International Assistance Operations – E. Wega (DPD)

Reports to all Deputy Ministers:

Assistant Deputy Minister Human Resources – Francis Trudel (HCM)

Assistant Deputy Minister International Platform – Dan Danagher (ACM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Corporate Planning, Finance and IT (Chief Financial Officer) – Anick Ouellette (SCM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Public Affairs – Stéphane Levesque (LCM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Strategic Policy – Heidi Hulan (PFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Global Issues and Development – Peter MacDougall (MFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister International Security and Political Affairs (Political Director) – Dan Costello (IFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Partnership for Development Innovation – Caroline Leclerc (KFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister International Business Development and Chief Trade Commissioner – Sara Wilshaw (BFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Trade Policy and Negotiations and Chief Trade Negotiator NAFTA – B. Christie (TFM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Consular, Security and Emergency Management (Chief Security Officer) – Cindy Termorshuizen (CFM)

Legal Advisor – Alan Kessel (JFM) – Special Deployment Position

Assistant Deputy Minister Sub-Saharan Africa – Mala Khanna (WGM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Europe, Arctic, Middle East and Maghreb – Sandra McCardell (EGM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Americas – Michael Grant (NGM)

Assistant Deputy Minister Asia Pacific – Paul Thoppil (OGM)

Executive Director and General Counsel – P. Hill (JUS)

Chief Audit Executive – J. B. Stephens (A) (VBD)

Director General, Inspection, Integrity and Values and Ethics – R. Sinclair (A) (ZID)

Corporate Secretary and Director General – C. Calvert (A) (DCD)

Chief of Protocol – S. Wheeler (XDD)

Ambassador for Women, Peace and Security – J. O’Neill (WPSA)

Head of the Anti-Racism Secretariat – M. Montrat (Sec) (DMAX)

Planning International Summits and Major Events – Vacant (DSMO)

Level 3 – Directors General

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Human Resources

HR Corporate Strategies and Operational Services – M. P. Jackson (HSD)

Assignments and Executive Management – V. Alexander (A) (HFD)

Workplace Relations and Corporate Healthcare – C. Houde (HWD)

Canadian Foreign Service Institute – L. Marcotte (CFSI)

Foreign Service Directives – M. Cameron (A) (HED)

Locally Engaged Staff – P. Kitnikone (A) (HLD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister International Platform

Client Relations and Mission Operations – L. Almond (AFD)

Planning and Stewardship – D. Schwartz (ARD)

Platform Corporate Services – D. Bélanger (AAD)

Platform Planning, Engagement and Results – A. Stirling (ABD)

Project Delivery, Professional and Technical Services – G. Stephens (A) (AWD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Corporate Planning, Finance and IT (Chief Financial Officer)

Financial Planning and Management – A. Boyer (SWD)

Financial Operations – S. Bainbridge (SMD)

Grants and Contributions Management – M. Collins (SGD)

Information Management and Technology (CIO) – K. Casey (SID)

Corporate Procurement, Asset Management and National Accommodation – D. Pilon (SPD)

Corporate Planning, Performance and Risk Management – L. Smallwood (SRD)

Senior IM/IT Project Executive – R. Dussault (SED)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Public Affairs

Development Communications – L. Belmahdi (LCA)

Public Affairs – Charles Mojsej (LCD)

Corporate and E Communications – C. Brisebois (LDD)

Trade Communications – V. Sharma (LCC)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Strategic Policy

Evaluation and Results – T. Denham (A) PRD)

Foreign Policy – P. Pena (POD)

International Assistance Policy – A. Smith (A) (PVD)

International Economic Policy – M. McDonald (PED)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Global Issues and Development

International Humanitarian Assistance – S. Salewicz (MHD)

Economic Development – C. Urban (MED)

Food Security and Environment – C. Campbell (MSD)

Health and Nutrition – J. Tabah (MND)

Social Development – L. Holts (A) (MGD)

International Organizations – A. Lalani (MID)

Innovative and Climate Finance Bureau – S. Szabo (MLD)

International Summits Programs – M. G. Mounier (DWD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister International Security and Political Affairs (Political Director)

International Security Policy – K. Hamilton (A) (IGD)

Peace and Stabilization Operations Program – G. Kutz (IRD)

Counter-Terrorism, Crime and Intelligence – M. Benjamin (IDD)

Human Rights, Freedom and Inclusion – C. Godin (A) (IOD)

International Crime and Counter-Terrorism – J. Loten (ICD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Partnership for Development Innovation

Engaging Canadians – S. Savage (KED)

Inclusive Growth, Governance and Innovation Partnerships – C. Hogan Rufelds (KGD)

Canadian Partnership for Health and Social Development – J.B. Parenteau (KSD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister International Business Development and Chief Trade Commissioner

Trade Portfolio Strategy and Coordination – C. Moran (BPD)

Trade Commissioner Service - Operations – S. Goodinson (A) (BTD)

Trade Sectors – R. Kwan (BBD)

Investment and Innovation – E. Kamarianakis (BID)

Regional Trade Operations and Intergovernmental Relations – F. Rivest (A) (BSD)

Chief Economist – M.F. Paquet (BED)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Trade Policy and Negotiations and Chief Trade Negotiator NAFTA

Associate Assistant Deputy Minister, Trade Policy and Negotiations – A. Alexander (A) (TFMA)

Trade Negotiations – K. Hembroff (TCD)

North America, Trade Policy and Negotiations – A. Renart (TND)

Market Access – D. Forsyth (TPD)

Chief Air Negotiator and Director General for Services, Intellectual Property and Investment – M. Shendra (A) (TMD-ANA)

Trade and Exports Control – S. Anand (TID)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Consular, Security and Emergency Management

Consular Policy – A-K. Asselin (CPD)

Consular Operations – B. Szwarc (A) CND)

Security and Emergency Management (Departmental Security Officer) – J. Sunday (CSD)

Security & Emergency Management Strategy and Policy – D. Stewart (A) (CED)

Reports to the Legal Adviser

Trade Law – S. Spelliscy (A) (JLT)

Legal Affairs – K. Knobel (A) (JLD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Sub-Saharan Africa

West and Central Africa – M. Lebleu (WWD)

Southern and Eastern Africa – T. Guttman (WED)

Pan-Africa – T. Khan (A) (WFD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Europe, Arctic, Middle East and Maghreb

European Affairs – R. Fry (EUD)

Middle East – J. Dutton (ESD)

Maghreb, Egypt, Israel and West Bank and Gaza – A. F. Whalen (A) (ELD)

Senior Arctic Official and Director General, Polar, Eurasia and European Affairs – H. Kutz (ECD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Americas

North America Strategy – E. Walsh (NGD)

North America Advocacy and Commercial Programs – L. Blais (NND)

South America and Inter-American Affairs – S. Cohen (A) (NLD)

Central America and Caribbean – S. Cesaratto (A) (NDD)

Geographic Coordination and Mission Support – S. Thissen (NMD)

Reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Asia Pacific

Southeast Asia – P. Lundy (OSD)

North Asia and Oceania – W. Epp (OPD)

South Asia – D. Hartman (OAD)

Level 4 – Outside of Main Organizational Structure

Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise – Sheri Meyerhoffer (CORE)

Source of information: Human resources Management System (HRMS)

In some cases, adjustments have been made by HFR to reflect the most current employee or positional information

Link to Global Affairs Canada Corporate Governance Structure

http://intra/department-ministere/assets/pdfs/committees-comites/CG_GC_OrgChart_Jan2017-EN.PDF

Updated on October 31, 2021

Network map

Alternative Text

| Canadian Regional Offices | 6 |

| Offices Abroad | 178 |

| Canada-based Staff | 2372 |

| Locally engaged staff | 5999 |

| Embassies | 78 |

| High Commissions | 22 |

| Offices | 24 |

| Representative Offices | 2 |

| Multilateral Missions | 11 |

| Consulates General | 25 |

| Consulates | 10 |

| Consular Agencies | 6 |

Response to international emergencies

Issue

- In response to an increasingly complex and volatile global context, Canada has in place a framework of crisis response tools and strategies.

- Canada provides consular services to Canadians in need, and technical and financial support for developing countries, as part of wider international life saving efforts.

- Global humanitarian needs have grown significantly in recent years, due to the increasingly protracted nature of conflict situations, rising food insecurity and forced displacement.

Context

Political violence, armed conflict and natural hazards are a prevalent feature of the current international context. Where the intensity demands a comprehensive global response, notably if catastrophic in nature or if the impact is transnational, Canada must be ready to react and contribute.

From 2010-2019 the number of active violent conflicts in fragile contexts has increased 128%. Absent political solutions, many of these conflicts are protracted with significant social, economic and security consequences. In addition, natural disasters, which affect some 350 million people each year, are increasing in magnitude and frequency due to climate change. In 2020, this resulted in $210 billion in financial losses. This type of emergency is highly visible and requires a timely response. These events have led to a near tripling in humanitarian need over the last decade and continue to rise. In 2021, approximately 235 million people across the world are in need of humanitarian assistance and protection, resulting in UN and Red Cross appeals exceeding US$37.5 billion. This is the highest of any annual global appeal to date.

At the same time, Canadians are increasingly mobile, and live and travel in areas of the world where civil and political instability, or the threat of natural disasters is more prevalent. Emergency management service demands are growing, as are Canadians’ expectations.

Coordination of international crises

Canada draws on a range of tools to respond to international emergencies, including: the network of Canadian embassies abroad; deployment of financial resources; or technical surge capacity and expertise as needed. In exercising its mandate to coordinate Government of Canada response to international crises, Global Affairs Canada provides a broad platform of facilities and personnel to enable a robust “all hazards” approach in preparing for, and mitigating against, impacts to Canadian interests overseas.

Global Affairs Canada monitors international incidents 24/7 to plan and prepare for international emergency response. When emergencies occur, Global Affairs Canada leads the coordination of interdepartmental task force groups and carries out cooperation with international and non-governmental entities, allies and partners.

Global Affairs Canada supports Canadians abroad through the delivery of consular services, including the provision of up-to-date travel advice and advisories for more than 230 destinations to ensure that Canadians are prepared for safe and responsible international travel. The Emergency Watch and Response Centre provides after-hours support to missions and consular clients through 24/7 operations. During a crisis, the centre may act as the first line of communication with Canadians abroad or with their families in Canada. Standing rapid deployment teams are trained and ready to deploy on short notice to provide surge capacity to the network of missions abroad.

The provision of emergency assistance, including the repatriation or evacuation of Canadians, is a function of the royal prerogative over international relations and is exercised by the Minister of Foreign Affairs pursuant to section 10 of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Act. Pursuant to the Emergency Management Act (2007), the Department is responsible for coordinating Canada’s response to international emergency events and supporting business continuity. The Minister of International Development has an important role in responses involving humanitarian assistance programming.

In 2020 and 2021, critical emergency consular operations included support to the Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752 (PS752) disaster and the repatriation of 62,580 Canadians and permanent residents from 109 countries during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Canada may also provide International Humanitarian Assistance in response to complex, protracted emergencies and natural disasters, and is among the top 10 contributors globally, providing over $800 million annually in recent years. This assistance is largely provided via humanitarian funding to experienced UN, Non-Governmental Organisation, and Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement partners. Humanitarian assistance represents a significant part of Canada’s total official development assistance (ODA).

In determining the level and composition of Canada’s funding in response to an emergency, the severity of the impact/crisis, the number of people affected, and the capacity of local/national authorities to respond is considered.

Canada’s humanitarian aid is people-centered, with a gender-responsive approach that is human rights-based and inclusive. It provides humanitarian assistance within a proven global system. Doing so avoids duplication of efforts, and allows for a proportional, timely, coordinated and needs-based response in line with consolidated and prioritized appeals.

Humanitarian assistance is guided by 4 core principles:

Humanity: Human suffering must be addressed wherever it is found.

Neutrality: Humanitarian actors must not take sides in hostilities or engage in activities of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature.

Impartiality: Assistance must be delivered solely on the basis of need, making no distinctions on the basis of nationality, race, gender, religion, class or political opinions.

Independence: Humanitarian assistance must be distinct from political, economic, military or other objectives.

The application of these principles helps organizations build trust and acceptance for their activities, particularly in armed conflicts, which is critical for establishing and maintaining access to affected populations.

In the case of natural disasters, Canada’s response to support the affected population is civilian-led, coordinated, needs-based, and provided upon request from the affected nation(s). A well-established, whole-of-government approach exists to respond to natural disasters abroad.

Depending on the scale of the disaster, Canada may need to deploy additional or targeted assistance beyond financial assistance to trusted partners. Canada’s tool kit supports:

- The provision of in-kind relief supplies and field hospitals, through partnership with the Canadian Red Cross;

- The deployment of humanitarian expertise; and,

- The use of a matching fund as a public engagement tool.

For example, in response to the recent Haiti earthquake (August 2021), Canada is providing $5 million to support humanitarian relief efforts as well as supplies from the stockpile managed by the Canadian Red Cross. In some cases, Canada may also launch matching funds with Canadian NGOs to increase public engagement and to support NGO fundraising efforts, as was done in response to Cyclone Idai (2019) in Malawi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

Following large-scale natural disasters, as a last resort when the ability to respond exceeds civilian capacity, the Canadian Armed Forces’ unique capabilities such as the Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) may also be engaged. Since 1998, Canada has sent the DART to help when natural disasters and crises have struck other countries and when local responders are overwhelmed. The most recent DART deployments include: Nepal earthquake (2015); Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines (2013); and Haiti earthquake (2010).

Beyond operational responses, Canada is actively engaged at the global level in multilateral and multi-stakeholder forums to enhance the effectiveness of the international humanitarian assistance system. Canada works to safeguard humanitarian access and uphold international humanitarian law through multilateral and country-level diplomatic engagement and advocacy, and has also helped establish international norms and standards on the protection of civilians.

Litigation update

Issue

Havana Syndrome

- A group of government employees and their dependants have commenced litigation against the Crown with respect to ‘Havana Syndrome’.

- The plaintiffs allege the Crown failed in its duty of care to them by not protecting their health and safety while at Canada’s embassy in Havana; [REDACTED].

- [REDACTED]

[REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

- [REDACTED]

Context

Havana Syndrome

In February 2019, an action commenced against the Crown in Federal Court by 9 employees of Global Affairs Canada and 18 of their dependants seeking damages in excess of $20 million as a result of what they referred to as ‘Havana Syndrome.’ The Attorney General has delivered a Statement of Defence on behalf of the Crown, denying any liability.

[REDACTED]

C. Global overview

Global trends

Issue

- A complex and destabilizing global landscape has repercussions for Canada’s international agenda. COVID‑19 has introduced further uncertainty, accentuating challenges to institutions, alliances, practices and norms, while demonstrating the importance of international cooperation. As Canada contributes to fighting the pandemic and promoting an inclusive, equitable and sustainable global recovery, it must do so with an eye to the geostrategic environment, and identify opportunities to shape the rules‑based system in a manner that supports its values and long-term national interests.

Context

Overview

Diverse inter-related geostrategic trends are imposing new strategic choices on Canada’s foreign policy. Four stand out. First, there has been a sharpening of great power competition, most importantly the rivalry between the United States and China, which affects the strategic choices of every country. Second, authoritarianism and illiberal populism persist in many countries, while even robust democratic systems are experiencing strains. Third, deepening inequality within and across countries is driving questions about who shapes and benefits from current national and global systems. This is occurring in tandem with deliberate action to roll back progress on human rights and gender equality in all regions and across some international bodies. Fourth, therole of technology, and those who develop and deploy it, is evolving rapidly. A more digital world offers significant potential to improve lives, but is also leading to increasing disruption across a wide range of economic, social and political spheres.

COVID-19 introduced new uncertainty to a global system already in flux, exposing the risks and opportunities of our interconnected world. The pandemic has exacerbated inequities and vulnerabilities, and significantly reversed poverty reduction and development gains, notably for women, children and marginalized groups. It has also demonstrated the importance of cooperation, and the key role played by multilateral bodies, including international financial institutions and many UN agencies, funds and programs. There has also been cooperation on global health and vaccines, such as the COVAX Facility, and for economic recovery, such as the World Bank COVID-19 Strategic Preparedness and Response Program. And yet, COVID-19 has also accentuated challenges facing institutions (such as the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), World Health Organization (WHO) and World Trade Organization (WTO)), and sparked reflections about self-reliance in strategic sectors. With the development of new vaccines, though inequitably distributed, there is a new focus among policy makers on the future strategic landscape and opportunities to revitalize a strained rules-based system.

Geopolitical competition, peace and security

The historic shift of geopolitical and economic power from the Atlantic to the Pacific is still underway as emerging Asian countries (including China and India) are projected to continue growing at a faster rate than advanced transatlantic economies. This is occurring at a moment when the system of agreed international laws and institutions that govern inter-state behaviour are under strain due to a confluence of factors, all of which contributes to an unpredictable international strategic environment. Shaping this environment is a key focus of the Biden administration, which has swiftly sought to re-establish U.S. leadership on a range of international issues, including by re-joining the Paris Agreement, re-engaging with the UN Human Rights Council, arranging high-level meetings with China and Russia, initiating nuclear discussions with Iran, hosting a climate summit, planning a summit for democracy and seeking to improve transatlantic cooperation. The quick agreement on a Roadmap for a Renewed Canada-U.S. Partnership outlines how our 2 countries can face a range of challenges, including on multilateral issues. While these shifts are welcome, [REDACTED]

For its part, China continues its economic, political and military ascent, overtly using levers of influence [REDACTED]. China is becoming a systemic actor in some areas, including technology, outer space, climate and energy, [REDACTED] while seeking to shape the context across multiple issues, regions and forums to align with the goals of the ruling regime. [REDACTED] (China was viewed unfavourably by majorities in every country in a 2020 Pew survey of 14 advanced economies).

The pandemic has sharpened a U.S.-China rivalry, and both are increasing pressure on third countries to align on key issues. While some bilateral cooperation and much trade will continue, the United States and China are seeking some degree of strategic decoupling, especially in advanced technology, putting the world on a path towards less digital and technological interoperability. [REDACTED]

Increased rancor between democratic and authoritarian states is another key trend whereby assertive authoritarian states such as [REDACTED]interfere in democratic processes abroad, seek to weaken multilateral work on democracy, human rights and media, and use coercive tactics for diplomatic and economic leverage, including arbitrary detentions of foreign citizens. Illiberal populists in [REDACTED] also weaken democratic institutions in the pursuit of nationalist goals [REDACTED]

These dynamics hinder multilateral action, including on global security challenges. Just in the last year, there have been coups in Myanmar and Mali, evidence of egregious human rights violations by Chinese authorities in Xinjiang, conflict in Tigray and Nagorno Karabakh, fighting between Hamas and Israel, border clashes between India and China, and political protests and violence in Colombia, Belarus and Haiti. Violent extremists (e.g. Daesh, Boko Haram, Al-Qaeda) continue to threaten, compounded in fragile states with low resilience. Protracted crises, notably in Syria, Libya, the DRC, Lebanon, Venezuela, Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Sahel, destroy lives and livelihoods with regional and international implications. Currently, no fragile and conflict affected state (FCAS) is on track to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals on hunger, health, gender equality and women’s empowerment, and millions of people continue to be displaced due to conflict and instability.

More peaceful regions and issues are also vulnerable to increased contestation. The Arctic, for example, is changing rapidly in the face of climate change, further opening to maritime navigation and resource exploration. While Arctic states remain committed to a rules-based, peaceful and stable Arctic region, growing interest from non-Arctic states will make this more challenging. Nuclear non‑proliferation challenges also remain (e.g. Iran, North Korea) though the revival of negotiations regarding Iran under the Biden administration is being met with cautious optimism. Non-traditional security issues, from health security (e.g. infectious diseases prevention and preparedness, concerns over the potential weaponization of biological agents) to space security, have also been given added primacy by the pandemic. Cyberspace is an increasingly active domain for geopolitical rivalry and criminal action, with a multiplication of malicious state-sponsored cyber activities, including misinformation and disinformation campaigns, and industrial espionage efforts.

More broadly, rising geopolitical tensions may make it more difficult to reach agreement among major powers, or to advance major multilateral initiatives. To address these challenges, multilateralism will continue to be practiced by the vast majority of states, but the mechanisms by which this proceeds will evolve.Where old forums no longer meet the challenge, it may be necessary to create new forums (i.e. ad hoc coalitions and plurilateral groupings) to address emerging issues in different ways.

Democracy, human rights and gender equality

Achieving greater respect for human rights, gender equality, and inclusion is a significant challenge in the face of eroding respect for human rights and democracy globally. For 2020, Freedom House recorded the 15th consecutive year of overall decline in democracy around the world. Connected with this trend, segments of the population in many countries feel excluded from decision-making or economic opportunities. In some liberal democracies, political polarization has increased the visibility of narratives questioning the integrity and effectiveness of democratic institutions and systems.

At the same time, a deliberate anti-human rights and gender backlash is targeting feminist movements and women’s rights, including sexual and reproductive health rights, gender equality and the rights of LGBTQ2+ persons. Meanwhile, Indigenous, Black, Asian and other racialized people feel the consequences of systemic racism and discrimination both in Canada and abroad. Persons with disabilities encounter barriers to accessing health care, social protection and employment, and are more susceptible to poverty, exclusion and violence. Indigenous peoples suffer disproportionately high rates of landlessness, malnutrition, maternal mortality, and displacement. Due to the pandemic, women and girls face particular health and socioeconomic threats, exacerbated by intersecting forms of discrimination and violence. Women remain systematically underrepresented in decision-making and leadership positions, whether in elected office, civil services, the private sector or academia, which increases the risk of their specific needs and interests being overlooked in policies, plans and budgets.

New and emerging technologies are double-edged swords for democracy and human rights. Such technologies allow regimes to violate human rights and weaken democratic institutions, and are used by non-state actors to commit abuses and undermine democracies. These technologies also enable and connect civil society, human rights defenders, and pro-democratic voices in support of freedom of expression and association, facilitating citizen engagement and the monitoring of rights violations.

Development, economics and trade

Economically, with divergent recoveries underway, much remains to be seen about how quickly vaccines will roll out beyond developed countries and how the evolving pandemic affects recovery efforts. The effects of the pandemic on global poverty and efforts to achieve the SDGs are expected to be long lasting. In 2020, the world experienced the single largest increase in global hunger ever recorded, and the World Bank estimated that COVID-19 pushed 119 to 124 million people into extreme poverty, representing the first increase in the global extreme poverty rate since 1998. Youth, women, workers with relatively lower educational attainment and the informally employed were hit hardest, and income inequality is likely to increase significantly, particularly in low-income and developing countries.

International migration experienced a significant shock from COVID-19. While regular migration routes have slowed/stopped, irregular migration routes have not, with significant negative impacts on migrants and the communities that host them. Despite COVID-19, remittance flows remained resilient in 2020, registering a small decline (1.6%). The fall in foreign direct investment (FDI) flows to low- and middle-income countries was more acute – excluding flows to China, those fell by over 30% in 2020.

Trade flows did better than had been feared in 2020 and are further rebounding in 2021. However, the international trade landscape may become more fragmented as geopolitical competition and activist industrial strategies create new distortions. The multilateral trading system, underpinned by the WTO, has struggled to accommodate emerging economic players and global issues. Two major challenges are the ongoing digital and technological transformation and the shift toward a greener global economy. New disruptive technologies and the rising power of big technology companies represent challenges for policymakers, notably as a growing share of economic activity as well as because everyday social and political interactions are mediated through digital tools and platforms.

The disruptions of the pandemic have also encouraged states to review their exposure to global risks and the resilience of key supply chains, notably for critical minerals, bio-manufacturing (pharmaceuticals, vaccines), food and high tech products and services. Many countries, including many of Canada’s larger trading partners, have leveraged pandemic recovery spending to reposition key sectors for a more digital and green future, and greater economic resiliency.

Meanwhile, international developmentremains an important domain for geopolitical influence among leading powers, including China, the United States and Japan. As the pandemic recovery continues, donors are struggling to preserve official development assistance levels due to domestic fiscal requirements. This has led to a renewed focus on aid and development effectiveness, including on “localisation” as a new way of approaching the ideal of local ownership, and greater coherence of humanitarian, development and peace efforts (triple nexus). Debt financing has become an acute issue as many developing countries had high debt loads before the crisis, which now limit their ability to respond to and move beyond the pandemic. International financial institutions are using all instruments at their disposal to help countries in need, offering unprecedented emergency financing facilities and new projects, while the G20 committed to temporarily suspend debt payments on the part of the poorest countries.

Looking forward

In this new and uncertain era, Canada needs all the tools at its disposal to navigate difficult terrain ahead. It will need to reinforce existing partnerships while pursuing non-traditional ones. It will need to invest, with others, in shaping the international order, including to protect, promote and reform elements of the existing rules-based system that are core to its interests and support its values. At the same time, Canada needs to be discerning and strategic in its prioritization of institutional and bilateral support, multilateral and technical initiatives, and domestic measures designed to protect national interests.

State of the global economy

Issue

- The global economy continues to rebound from the COVID-19 recession, but momentum is weakening. As a group, advanced economies are rebounding much faster and are expected to emerge from the pandemic with far less economic scarring than most emerging and developing economies, many of which are facing downgraded prospects in recent months.

- The Canadian economy is forecasted to grow by 5.7% in 2021 and 4.9% in 2022 (IMF), thanks to the ongoing vaccine rollout and robust U.S. demand.

- The pandemic has accelerated structural shifts towards the digital and green economy, with many countries launching recovery plans and investments to increase supply chain resilience and to support strategic sectors. Trends to watch include COVID-19 variants’ impacts on recovery; growing social and economic inequalities; exposure of highly indebted states; rapidly rising energy costs; and potential inflation.

Context

Global growth

The most recent quarterly economic outlooks released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) both project a continuing global economic recovery, albeit with slowing momentum and persistent divergences between the prospects for advanced and developing countries. The IMF’s current expectation is that after contracting by 3.3% in 2020, the global economy is projected to grow by 5.9% in 2021, and by 4.9% in 2022. While this represents a much better outcome than previously feared, global income will still be trillions of dollars less than was expected before the crisis hit, and below the headline indicators of the global recovery in progress, the prospects for many countries are being downgraded.

Both institutions also warn about similar broad risks in the recovery. First, that the economic rebound will be highly uneven within and between countries, threatening to leave many countries and more vulnerable people behind. Advanced economies, led by the United States, are expected to move more quickly toward closing the gap with what had been their pre-pandemic growth trend. The IMF projects that advanced economies will regain their pre-pandemic trend path in 2022 and exceed it by 0.9% in 2024. Meanwhile, many emerging market and developing economies, apart from China, face significant economic scarring in the form of lost growth relative to what had been forecast before the pandemic. The IMF projects that these countries will remain 5.5% below their pre-pandemic forecast in 2024 [REDACTED].

[REDACTED].