G7 Charlevoix Progress Report

Women’s Economic Empowerment as a Driver for Innovation, Shared Prosperity and Sustainable Development

G7 Accountability Working Group (AWG)

Accountability and transparency are core G7 principles that help maintain the credibility of G7 Leaders’ decisions. At the Summit in 2007 in Heiligendamm, Germany, G8 members introduced the idea of building a system of accountability. In 2009, the Italian Presidency formally launched this mechanism in L’Aquila and approved the first, preliminary Accountability Report and the Terms of Reference for the G7 Accountability Working Group (AWG). Since the first comprehensive report was issued at Muskoka in 2010, the AWG has produced a comprehensive report reviewing progress on all G7 commitments every three years, along with sector-focused accountability reports in interim years. These reports monitor and assess the implementation of development and development-related commitments made at G7 Leaders’ Summits, using methodologies based on specific baselines, indicators, and data sources. The reports cover commitments from the previous six years and earlier commitments still considered to be relevant. The AWG draws on the knowledge of relevant sectoral experts and provides both qualitative and quantitative information. For 2018, the Canadian Presidency chose Women’s Economic Empowerment as the theme for the Charlevoix Progress Report.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Chapter 1 - An Approach to Growth and Sustainable Development that is Responsive to and Inclusive of Women - the G7 Development Agenda

- Chapter 2 - G7 Policy Priorities and Funding for Women’s Economic Empowerment

- Chapter 3 - Making Strides in Women’s Economic Empowerment: G7 Initiatives

- Chapter 4 - Conclusions

- Annexes

Executive Summary

G7 Leaders are committed to supporting women’s economic empowerment to help ensure women and girls achieve their full potential. Gender equality, the empowerment of women and girls, and the promotion and protection of their human rights are critical to building peace, reducing poverty, growing inclusive economies and achieving sustainability for a prosperous world. To advance women’s economic empowerment, it is crucial to promote relevant public policies across all socio-economic sectors. This includes equal access to quality education, quality health care and economic opportunities, including land, capital, and credit as well as global value chains. It is also essential for women to participate equally in decision-making at all levels, and for all to benefit fully from social protections that prevent and address exploitation and abuse. When women have full and equal ability to participate in the economy, countries and communities experience broader economic growth and lasting change that benefits everyone.

As such, G7 members identified women’s economic empowerment as a shared development priority in 2015. The Charlevoix Progress Report outlines the progress made by the G7 in implementing the 2015 Elmau commitment on women’s economic empowerment, specifically to “support our partners in developing countries and within our own countries to overcome discrimination, sexual harassment, violence against women and girls and other cultural, social, economic and legal barriers to women’s economic participation.” In both 2015 and 2016, G7 members have allocated 28% of their official development assistance (ODA) funds to help developing countries build and strengthen women’s economic empowerment across various sectors. G7 members and the EU have also supported projects and programs to help eliminate violence against women allocating US$ 529 million towards this goal in 2015 and 2016.

In 2017, G7 Leaders further committed to advancing this objective by adopting the G7 Roadmap for a Gender-Responsive Economic Environment. During its 2018 G7 Presidency, Canada continued this work by focusing on investing in growth that works for everyone, emphasizing women and girls as a central component of these efforts. Canada created the Gender Equality Advisory Council for its presidency to ensure that gender equality and women’s empowerment are integrated across all themes, activities and initiatives while amplifying women’s voices and leadership.

As the first detailed G7 progress report on women’s economic empowerment, The Charlevoix Progress Report provides a preliminary analysis of the issues women and girls are facing and highlights the efforts made by G7 countries and the European Union to economically empower women in developing countries. It showcases G7 members’ commitment to strengthening and supporting women’s economic empowerment through their international assistance policies, strategies and priorities, as well as through their financial contributions. The various examples included in the Report also highlight the important role played by civil society, women’s rights groups and the private sector in promoting women’s economic empowerment, and the necessity of positively engaging men and boys.

G7 members have made considerable investments in fostering an enabling environment for gender equality and women’s economic empowerment, but much still remains to be done. The G7 will continue to focus on addressing these barriers, in order to foster sustainable growth so that no one and no country will be left behind.

Chapter 1 - An Approach to Growth and Sustainable Development that is Responsive to and Inclusive of Women - the G7 Development Agenda

Snapshot

- The G7 sees women’s economic empowerment and entrepreneurship as drivers for innovation, inclusive economic growth and sustainable development.

- The G7 recognizes the large number of barriers to women’s economic empowerment including restrictive social norms or cultural barriers, an uneven burden of unpaid work and care, unequal access to information and to digital technologies, marginalization in decision-making processes, discriminatory laws and lack of legal protections, violence against women, sexual exploitation and abuse, inadequate access to health care, and malnutrition.

- The G7 remains committed to strengthening women’s equal access to well-paid job opportunities, quality education and training, productive resources, land, financial and digital assets, as well as promoting an equal distribution of unpaid care work.

- G7 and other international commitments to gender equality and women’s and girls’ empowerment must be complemented by improved, sex-disaggregated data collection methodologies and measurements to enhance accountability.

Gender equality is an important part of the foundation for a prosperous world. Without dedicated efforts to address and eliminate gender inequality and discrimination experienced by women and girls, global development targets will remain elusive. Studies indicate that an increase in female labour force participation results in faster economic growth.Footnote 1 A new report released by the World Bank Group finds that if women have the same lifetime earnings as men, global wealth would increase by US$23,620 per person, on average, in the 141 countries studied for a total of US$160 trillion per annum.Footnote 2 At the 2015 Summit, G7 Leaders emphasized that: “Women’s economic participation reduces poverty and inequality, promotes growth and benefits all. Yet women regularly face discrimination which impedes economic potential, jeopardizes investment in development, and constitutes a violation of their human rights.” At the same Summit, G7 Leaders also committed to investing in women’s entrepreneurship as “a key driver of innovation, growth and jobs.”

G7 members are committed to taking concrete action to support women and girls, to allow them to realize their full potential. Evidence shows that gender equality, as well as the empowerment of women and girls are significant factors to building peace, reducing poverty and achieving sustainability.

Removing systemic barriers and increasing greater access to and control over assets such as land, housing and capital, advances gender equality and the empowerment of women which positively impacts the economy of all nations. Women already generate nearly 40% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP), and there remains an untapped potential for further growth led by women. The OECD estimates that a 50% reduction in the gender gap in labour force participation could lead to an additional gain of about 6% in GDP by 2030, and a further 6% gain (12% in total) if gender gaps are completely eliminated.Footnote 3 The socioeconomic benefits of gender equality cannot be ignored.Footnote 4

This chapter provides an overview of the evolution of women’s economic empowerment. This G7 priority aligns with recent international development frameworks, which put women and girls at the centre of development efforts.

1.1 - Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: Pillars for Transformative Growth and Development

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, the World Humanitarian Summit’s Agenda for Humanity and the Grand Bargain, the Paris Agreement, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, and the United Nations Global Compact, all include references to gender equality or equity, and in some cases also include concrete commitments and actions to achieve gender equality and to empower women and girls. These international frameworks build on the foundational work of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, and offer increased impetus towards achieving gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. Women’s economic empowerment is critical to achieving the 2030 Agenda. [See Textbox 1: Definition of Women’s Economic Empowerment].

Textbox 1: Definitions of Women’s Economic Empowerment

While there is currently no single definition of women’s economic empowerment (WEE), the OECD’s version is widely employed: “the capacity of women and men to participate in, contribute to and benefit from growth processes in ways that recognize the value of their contributions, respect their dignity and make it possible to negotiate a fairer distribution of the benefits of growth.”Footnote 5

Other comprehensive definitions expand on the OECD definition to bring in elements of agencyFootnote i and resilience. A Policy Brief from UN Women (2012) defines women’s economic empowerment as “increasing the ability of women to bring about change that drives valuable outcomes as a result of their increased economic capabilities and agency”Footnote 6 including elements of participation (in markets, labour) but also in effecting changes to markets, the gender division of labour, access to resources and influencing institutions. The significance and centrality of agency is further reinforced in Laszlo et al.’s 2017 definition noting that women who are economically empowered are increasingly able to “acquire access to, and control over, economic resources, opportunities and markets, enabling them to exercise agency and decision-making power to benefit all areas of their lives.”Footnote 7

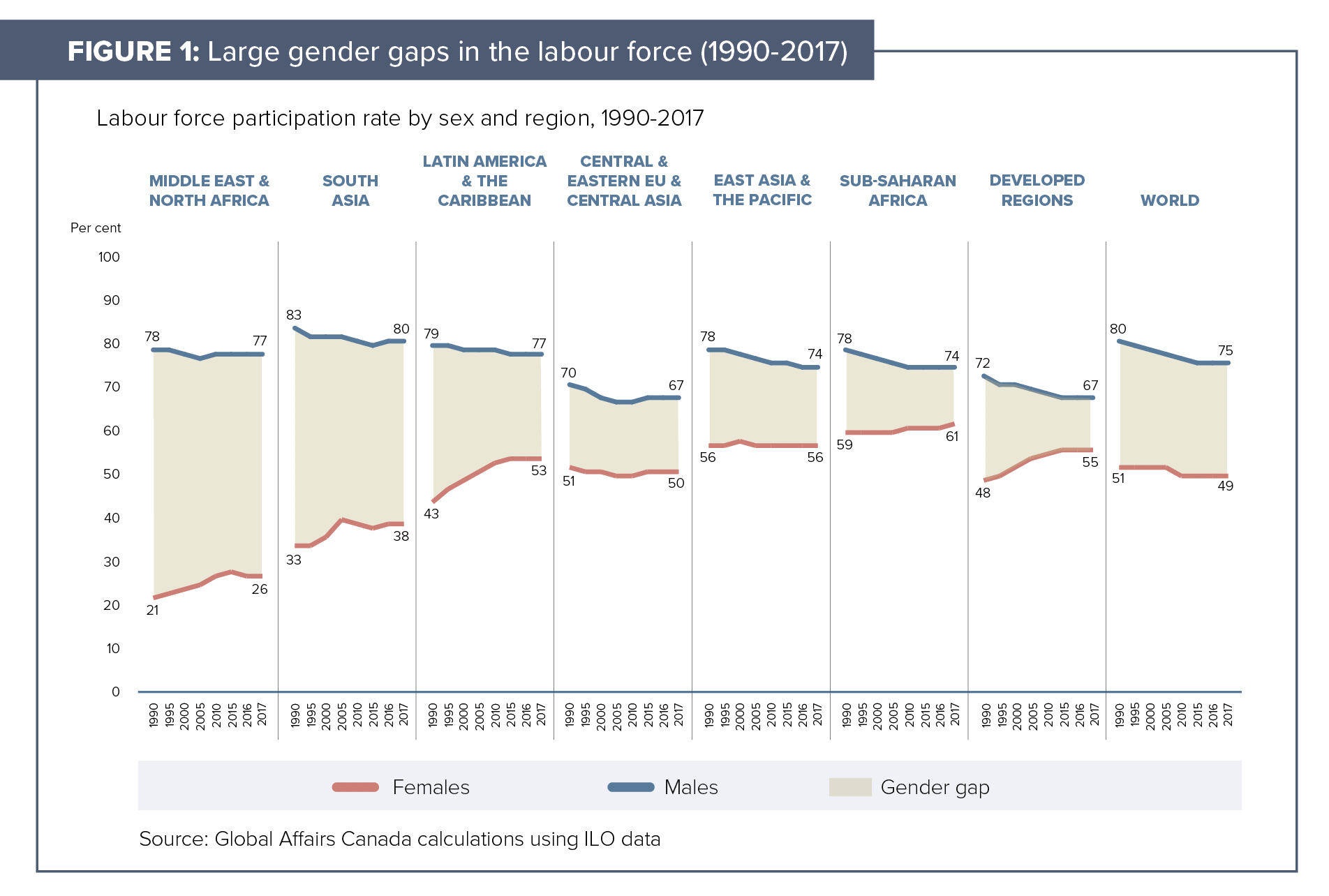

Despite some important social development gains for women over the past three decades (including reduced maternal mortality and improved access to primary education),Footnote 8 progress on gender equality has overall been uneven, and the gains made, in many instances, are fragile and women’s economic participation remains weak. The 20-year review of the Beijing Platform for Action: inspiration then and now found that “discriminatory norms, stereotypes and violence remain pervasive, evidencing gender-based discrimination that continues to be deeply entrenched in the minds of individuals, institutions and societies.” The review also documents the many other barriers and constraints to empowerment and equality including vulnerabilities arising from conflicts, financial and economic crises, climate change and volatile food prices.Footnote 9 The prevalence of women in informal employment and in poor working conditions, as well as the overwhelming burden of care work that women and girls carry and its associated impacts on women’s participation in the labour market, earnings, pension gaps and retirement savings, also limits equality between men and women, and women’s economic empowerment (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Large gender gaps in the labour force (1990-2017)

Text version

| Central & Eastern EU & Central Asia | Developed Regions | East Asia & the Pacific | Latin America & the Caribbean | Middle East & North Africa | South Asia | Sub-Saharan Africa | World | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| 1990 | 51 | 70 | 48 | 72 | 56 | 78 | 43 | 79 | 21 | 78 | 33 | 83 | 59 | 78 | 51 | 80 |

| 1991 | 51 | 70 | 48 | 72 | 56 | 78 | 44 | 79 | 21 | 78 | 32 | 83 | 59 | 78 | 51 | 80 |

| 1992 | 51 | 70 | 48 | 71 | 56 | 78 | 44 | 79 | 21 | 78 | 32 | 82 | 59 | 78 | 52 | 80 |

| 1993 | 51 | 70 | 48 | 71 | 56 | 78 | 45 | 79 | 22 | 78 | 33 | 82 | 59 | 78 | 51 | 80 |

| 1994 | 51 | 69 | 49 | 70 | 56 | 78 | 45 | 79 | 22 | 78 | 33 | 82 | 59 | 77 | 51 | 80 |

| 1995 | 50 | 69 | 49 | 70 | 56 | 78 | 46 | 79 | 22 | 78 | 33 | 81 | 59 | 77 | 51 | 79 |

| 1996 | 50 | 69 | 49 | 70 | 57 | 78 | 46 | 79 | 22 | 78 | 33 | 81 | 59 | 77 | 51 | 79 |

| 1997 | 50 | 68 | 50 | 70 | 57 | 78 | 47 | 79 | 22 | 78 | 34 | 81 | 59 | 77 | 51 | 79 |

| 1998 | 50 | 68 | 50 | 70 | 57 | 78 | 47 | 79 | 22 | 77 | 35 | 81 | 59 | 76 | 51 | 79 |

| 1999 | 50 | 68 | 51 | 70 | 57 | 77 | 48 | 79 | 23 | 77 | 35 | 81 | 59 | 76 | 51 | 79 |

| 2000 | 50 | 67 | 51 | 70 | 57 | 77 | 48 | 78 | 23 | 77 | 35 | 81 | 59 | 76 | 51 | 78 |

| 2001 | 50 | 67 | 51 | 70 | 57 | 77 | 48 | 78 | 23 | 76 | 36 | 81 | 59 | 76 | 51 | 78 |

| 2002 | 49 | 66 | 52 | 70 | 57 | 77 | 49 | 78 | 23 | 76 | 37 | 81 | 59 | 76 | 51 | 78 |

| 2003 | 49 | 66 | 52 | 69 | 56 | 77 | 49 | 78 | 24 | 76 | 38 | 81 | 59 | 75 | 51 | 78 |

| 2004 | 49 | 66 | 52 | 69 | 56 | 76 | 50 | 78 | 24 | 76 | 38 | 81 | 59 | 75 | 51 | 78 |

| 2005 | 49 | 66 | 53 | 69 | 56 | 76 | 50 | 78 | 24 | 76 | 39 | 81 | 59 | 75 | 51 | 77 |

| 2006 | 49 | 66 | 53 | 69 | 56 | 76 | 51 | 78 | 25 | 76 | 39 | 81 | 59 | 75 | 51 | 77 |

| 2007 | 49 | 66 | 54 | 69 | 56 | 76 | 51 | 78 | 25 | 76 | 39 | 81 | 59 | 75 | 50 | 77 |

| 2008 | 49 | 66 | 54 | 69 | 56 | 75 | 52 | 78 | 26 | 76 | 39 | 80 | 60 | 75 | 50 | 77 |

| 2009 | 49 | 66 | 54 | 69 | 56 | 75 | 52 | 78 | 26 | 76 | 39 | 80 | 60 | 75 | 50 | 77 |

| 2010 | 49 | 66 | 54 | 68 | 56 | 75 | 52 | 78 | 26 | 77 | 38 | 80 | 60 | 74 | 49 | 76 |

| 2011 | 49 | 66 | 54 | 68 | 56 | 75 | 52 | 78 | 26 | 77 | 37 | 79 | 60 | 74 | 49 | 76 |

| 2012 | 50 | 67 | 54 | 68 | 56 | 75 | 53 | 77 | 26 | 77 | 37 | 79 | 60 | 74 | 49 | 76 |

| 2013 | 50 | 67 | 55 | 68 | 56 | 75 | 53 | 77 | 26 | 77 | 37 | 79 | 60 | 74 | 49 | 76 |

| 2014 | 50 | 67 | 55 | 67 | 56 | 75 | 53 | 77 | 26 | 77 | 37 | 79 | 60 | 74 | 49 | 76 |

| 2015 | 50 | 67 | 55 | 67 | 56 | 75 | 53 | 77 | 27 | 77 | 37 | 79 | 60 | 74 | 49 | 75 |

| 2016 | 50 | 67 | 55 | 67 | 56 | 74 | 53 | 77 | 26 | 77 | 38 | 80 | 60 | 74 | 49 | 75 |

| 2017 | 50 | 67 | 55 | 67 | 56 | 74 | 53 | 77 | 26 | 77 | 38 | 80 | 61 | 74 | 49 | 75 |

The UN High-Level Panel (HLP) for Women’s Economic Empowerment found four systemic barriers to women’s economic empowerment that affect women’s ability to participate in the economy: discriminatory laws and a lack of legal protection; the failure to reduce and redistribute unpaid household work and care; a lack of access to financial, digital and property assets; and adverse social norms.Footnote 10 Barriers to women’s economic participation also have negative impacts on businesses, communities and national economies. Tackling economic disparities must therefore address the broad-ranging social and other systemic barriers to gender equality and women’s participation in the workforce, as well as the practical constraints to transformative growth and development.

Improving the livelihoods of women and fostering equal economic opportunity is a universal challenge (see Figure 2 on Inequality in the Workforce between Women and Men – UN Stats, The World’s Women, 2015). The World’s Women Report further highlights that in 2015 only 50% of working-age women were in the labour force, compared to 77% of working-age men.Footnote 11 Addressing gender equality in the world of work must begin with an examination of the barriers to women’s economic empowerment.

1.2 - The G7 Agenda for Women’s Economic Empowerment

Gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls have been long-standing priorities for the G7 (see Textbox 2: Brief History of G7/G8 commitments to gender equality and women’s economic empowerment). Building on these commitments, women’s economic empowerment was identified as a top G7 development priority in 2015. More recently, as part of the 2017 Roadmap for a Gender-Responsive Economic Environment, G7 countries affirmed the importance of eliminating violence against women and girls in public and private spheres, and to address structural barriers to women’s economic empowerment linked to discriminatory practices, gender stereotypes, negative social norms, and to harmful attitudes and behaviours.

G7 Leaders at the 2017 Taormina Summit further focused on the structural policies that are likely to have the greatest impact on promoting gender equality through enabling women’s labour-force participation, entrepreneurship and economic empowerment. The Taormina Roadmap outlines three core priorities, as well as corresponding actions and recommendations to foster the economic empowerment of women and girls. The core priorities are:

- Increasing women’s participation, and promoting equal opportunities and fair leadership-selection processes at all levels of decision-making;

- Strengthening the foundation of women’s access to decent-quality jobs; and,

- Eliminating violence against women and girls throughout their lives.Footnote 12

(See Annex A for the G7 Roadmap for a Gender Responsive Economic Environment).

During Canada’s 2018 G7 Presidency, gender equality – which is fundamental for the fulfillment of human rights and is a social and economic imperative– is a top priority. Two of the five themes of the Charlevoix Summit are: Investing in Growth that Works for Everyone; and Advancing Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment. Furthermore, Gender Equality Advisory Council for Canada’s G7 Presidency helped promote a transformative G7 agenda, and supported Leaders and ministers in ensuring that gender equality and gender analysis are integrated across all themes, activities and outcomes of Canada’s G7 Presidency.

Textbox 2: Brief History of G7/G8 commitments to gender equality and women’s economic empowerment

1990: Houston, USA – Committed to improved educational opportunities for women and their greater integration into the economy (Economic Declaration, para 53).

1998: Birmingham, UK – Committed to recognize that all people, men and women deserve the opportunity to contribute to and share in national prosperity through work and a decent standard of living (Final Communiqué, para 13).

2002: Kananaskis, Canada – Committed to improving education for girls in all countries with significant gender disparities (A New Focus on Education for All, page 3).

2004: Sea Island, USA – Committed to launch microfinance initiatives to increase economic opportunities and business training for empowering women (G8 Action Plan: Applying the Power of Entrepreneurship to the Eradication of Poverty).

2007: Heiligendamm, Germany – Committed to investing and being responsible in gender equality for the social dimension of globalization (Summit Declaration: Growth and Responsibility in the World Economy, para 21).

2008: Hokkaido Toyako, Japan – Committed promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment as a principle in G8 development cooperation through mainstreaming and specific actions. (Leaders Declaration, para 41).

2010: Muskoka, Canada – Committed, endorsed and launched the Muskoka Initiative to significantly reduce the number of maternal, newborn and under five child deaths in developing countries (Declaration: Recovery and New Beginnings, para 9).

2011: Deauville, France – Committed to support democratic reform around the world and to respond to the aspirations for freedom, including freedom of religion, and empowerment, particularly for women and youth (Leaders’ Declaration, para 2).

2014: Brussels, EU – Committed to show unprecedented resolve to promote gender equality, to end all forms of discrimination and violence against women and girls, to end child, early and forced marriage and to promote full participation and empowerment of all women and girls (Summit Declaration, para 40).

2015: Elmau, Germany – Committed to women’s economic empowerment, entrepreneurship, vocational training, maternal health, and overcome sexual violence in conflict, and ending violence against women (Leaders’ Declaration).

2016: Ise-Shima, Japan – Committed to creating a society where all women and girls are empowered and actively engaged for sustainable, inclusive and equitable economic growth through education and training, and promoting active role in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) fields (Leaders’ Declaration).

2017: Taormina, Italy – Committed to mainstreaming gender equality into all the G7 policies and welcomed the important contribution provided by the W7. To foster the economic empowerment of women and girls, G7 members furthermore adopted the first “G7 Roadmap for a Gender-Responsive Economic Environment” (Leaders’ Declaration, para 18).

Chapter 2 - G7 Policy Priorities and Funding for Women’s Economic Empowerment

Snapshot

- G7 members have made important investments in fostering an enabling environment for women’s economic empowerment, helping to overcome discrimination, sexual harassment, violence against women and girls, and other cultural, social, economic and legal barriers to women’s participation in the economy.

- G7 members have made notable contributions to advancing women’s equal rights and economic empowerment through specific policies, and international-assistance programmes and initiatives as illustrated in the chapter.

- The active engagement of partners, such as civil-society organizations, women’s rights organizations and movements, and private companies, within their own and in partner countries, is seen as essential to achieving women’s economic empowerment, as is the positive engagement of men and boys.

G7 members play an important role in strengthening and supporting women’s economic empowerment. To promote gender equality and to advance women’s economic empowerment, G7 members have integrated this commitment into their international-assistance priorities, policies and strategies as outlined below. Significant financial contributions have been made to increase women’s access to economic opportunities and to assist countries in the establishment and implementation of laws, policies and institutions supporting women’s economic empowerment.

This report assesses progress on implementing the 2015 Elmau commitment by measuring two indicators. The first is G7 support that directly enables women’s economic participation by targeting gender equality as a principal or significant objective in economic and productive sectors and in enabling sectors (such as education and training). Section 2.2 Table 1 provides a breakdown of G7 official development assistance (ODA) in these areas.

The second indicator focuses on support for women to overcome violence, which harms them and reduces their ability to participate economically. Section 2.2 Table 2 provides a breakdown of ODA focused on eliminating violence against women. In addition to drawing on data from the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC), the commitment to eliminate violence against women allows G7 members to report on their own activities in support of overcoming of barriers to women’s economic participation, in keeping with the flexible approach and broad views expressed in the commitment’s language.

2.1 - Policy Priorities

Canada

Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy and Commitments to Women’s Economic Empowerment

Canada is committed to gender equality and women’s economic empowerment as the most effective approach to achieving sustainable growth that works for everyone. Its Feminist International Assistance Policy recognizes the transformative impact women and girls, including adolescent girls, can have when they are able to reach their full economic potential.

A Holistic Approach

In keeping with Agenda 2030, Canada recognizes that global challenges are interconnected and require a coordinated response. To best increase women’s economic empowerment, Canada uses a holistic approach - one that includes diplomacy, trade, security and the expertise of various partners, including a wide range of Canadian government departments and agencies, and the private sector. This approach seeks innovative solutions and partnerships to challenge traditional models of international assistance and accelerate progress towards sustainable development. For example, Canada has established its new development-finance institute, FinDev Canada, to build more partnerships with businesses in developing countries, especially those operated by women and youth. Canada is also committed to a progressive trade agenda that fully considers gender equality during trade negotiations and incorporates greater gender considerations in its free trade agreements (FTAs), demonstrated by the new trade and gender chapter of the modernized Canada-Chile FTA.

Canada also believes it is essential to create an enabling environment for women’s economic rights to be realized and upheld. To this end, it committed $650 million over three years to close the persistent gaps in sexual and reproductive health and rights for women and girls, recognizing that women must have control over their own sexual and reproductive health choices to take full advantage of economic opportunities. Canada also seeks to promote women’s access to technical and vocational education and training, as well as to advance women’s integration in dynamic value chains that are economically and environmentally sustainable. This increases accesses to decent work, helps women and girls become more competitive and innovative, and increases their employment and market opportunities. By seeking to expand the ability of governments to enable women’s full participation in decision-making through support of gender-based analyses and gender-responsive budgeting in public management, Canada is also helping to support women’s leadership in businesses, communities and institutions, and tackle their economic and political marginalization.

The sustainability of economic empowerment can be fragile, as a change in one’s conditions can quickly erase the gains of years of hard work, leading to destitution and disempowerment. As such, financial inclusion, improved social protections, and the adoption of techniques that mitigate the impacts of climate change, are important policy objectives for Canada to increase women’s economic resilience, particularly in rural areas.

Further examples of concrete initiatives for Canada to increase women’s economic empowerment are noted below:

Advancing Women’s Economic Rights and Leadership

In 2017, Canada made a strategic decision to make women’s rights organizations and movements key partners in the design and implementation of international assistance initiatives, recognizing their critical role in achieving social change for gender equality. Canada committed $150 million to the Women’s Voice and Leadership Program to support local women’s organizations and movements that advance women’s rights in developing countries.

Canada’s International Development Research Centre’s Growth and Economic Opportunities for Women Program opens promising avenues with new approaches to address disempowerment resulting from the disproportionate burden of care shouldered by women. This seeks to address gender norms, particularly social and family expectations regarding unpaid work, which constitute a systemic barrier to women’s economic empowerment.

Decent Jobs and Women-Led Enterprises

Canada contributed $20 million to the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative, a World Bank mechanism that aims to promote women’s entrepreneurship in developing countries and $15 million to the Digital Livelihoods: Youth and the Future of Work at Scale project, which trains women and youth to use digital tools.Footnote ii These initiatives help women entrepreneurs access capital, networks and markets in higher value-added sectors.

France

Women’s economic empowerment, a priority for France’s external action

France considers women’s economic empowerment as a driving vector of progress and sustainable development. In full conformity with President Macron’s commitment to make gender equality the “great cause” of his five-year term, France adopted its gender strategy for 2018–2022 at the last Interministerial Committee for International Cooperation and Development (CICID) in February, 2018. The strategy outlines France’s priorities for the promotion of gender equality in its external action and acts as a roadmap for the French Ministry of Foreign affairs’ implementing agencies, such as the French Agency for Development (AFD).

As professional inequalities continue to undermine women’s full potential, and have a direct economic impact on societies, France highlights women’s economic empowerment as one of its five priorities. In accordance with its commitment to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, France is strongly committed to making women take the lead to reach sustainable development. To take concrete steps to make gender equality a reality, France commits to increase girls’ and women’s access to services and more particularly to social services such as lifelong education and sexual and reproductive health and rights.

France also identifies access to land property, financial services, transport infrastructures, legal services, and information and communication technologies as essential conditions for women’s economic empowerment. More specifically, France targets the elimination of gender stereotypes in the world of work, helping women to successfully integrate into sectors where they are currently under- represented, they are active but not recognized such as in climate change and ecological transition or to create their own profitable companies. It also recognizes the role of public policies in guaranteeing women’s employment, social protection, and services and security at the workplace.

France promotes humanitarian-aid programmes designed to guarantee women’s livelihoods in crisis and post-crisis situations. Finally, France promotes women’s role in mitigation and adaptation to climate change. By accounting for 60 to 80% of the agricultural production in developing countries, women contribute to rural economy and food security, a sector that is essential but under threat by climate change. Climate variations put women in a very vulnerable and insecure economic position. France strongly defended the integration of a gender dimension in the Paris Climate Agreement and in the Gender Action Plan of the UNFCCC to specifically integrate these variations into climate change policies, negotiations and finances at the local and international level.

France’s recommended approach

A rights-based approach

Gender inequality in the workplace is often fomented by patriarchal and cultural standards. The fact that women are not always aware of their rights exacerbates their silence and can lead to resignation. France fosters a rights-based approach to development programmes so that women gain better knowledge of their country’s constitutional and international commitments, and to delegitimize professional discrimination.

A cross-cutting and lifecycle approach

Cultural and structural factors contribute to unequal access to economic opportunities. Women’s access to economic opportunities depends on their access to education and professional training, to sexual and reproductive health and rights, their right to decide when to marry and have children, the distribution of domestic and family responsibilities, etc. Therefore, France understands gender issues as cross-cutting and all-encompassing, and encourages a lifecycle approach, centered on specific need and age categories. Young girls and adolescents deserve special attention as they face particular challenges that can increase their vulnerability, such as unequal access to education, child marriage and early pregnancy.

Engaging men and boys

Gender equality cannot be achieved without the involvement of men and boys. They play a critical role in terms of improved health outcomes, fighting gender-based violence and promoting the elimination of harmful stereotypes and practices. Young men and boys are targeted through programmes that focus on youth and adolescent sexual and reproductive health, such as the French Muskoka Fund, implemented in eight West and Central African countries.

Example of a French flagship programme aimed at improving women’s economic empowerment

AFD and TSKB’s project for female-friendly companies in Turkey

In 2017, AFD and the Turkish Development Bank (TSKB) launched a programme to foster women’s economic empowerment, with the aim of improving occupational health and safety conditions, and promoting women’s employment in Turkey.

Thanks to a €100,000,000 loan from AFD, TSKB will dedicate a credit line to fund Turkish companies’ investments in these areas to encourage female-friendly companies.

TSKB will raise companies’ awareness of issues concerning women’s employment and professional equality by giving them training and tools on topics such as equal treatment in labour relations and salaries, specific economic rights such as maternity leave and gender-based violence.

Germany

Gender Equality – a key priority for German Development Cooperation

Gender equality is a target of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and an explicit goal, a principle and a quality criterion that runs throughout German development cooperation. To this end, the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) has made a commitment to follow a human rights based approach.

With its 2014 cross-sectoral strategy on Gender Equality in German Development Policy, BMZ established a three-pronged-approached to the promotion of gender equality and women’s empowerment consisting of gender mainstreaming, empowerment and policy dialogue.

The Development Policy Action Plan on Gender Equality 2016- 2020 (GAP II) lays down concrete steps for implementing the binding gender equality strategy and the three-pronged approach. Annual road maps implement GAP II. Thematic areas and strategic goals are selected each year and measures for implementation are presented. Women’s economic empowerment is a key goal in the Gender Action Plan and thus a priority for German Development Cooperation.

Germany is also committed to promote gender equality domestically, and passed several new legislative and non-legislative initiatives to promote women’s economic empowerment. In 2015, the Act on the Equal Participation of Women and Men in Leadership Positions in the Private and the Public Sector came into effect. In July 2017, a new Act to Promote Transparency in wage structures went into force. Further, Germany amended its Parental Allowance and Parental Leave legislation, to promote partnership and improve the reconciliation of family and work. Finally, woman empowerment is also measured within the German Sustainable Development Strategy.

The following domestic and international initiatives can serve as best practice examples:

Economic Integration of Women in the MENA region (EconoWin)

“When women work, economies win”. Since 2010, the GIZ EconoWin programme, has successfully improved the conditions for the economic participation of women in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia. Private sector, civil society and governmental partners have thrived jointly in promoting the active participation of all men AND women.

The project worked in four areas: 1) addressing societal and cultural stereotypes within the area of ‘women and work’ through an initiative 2) promoting female talent through female mentoring, professional orientation and career guidance, 3) professionalizing the management of gender diversity in the private sector and 4) integrating women from rural areas into the labour market and upscaling their products.

The project has produced tremendous results. 6,000 participants were reached through 325 film events on the subject women and work; 150 sector representatives publicly discussed the implementation of supportive labour laws for women and families at roundtable talks; and 30 regional business advisors and 25 business associations were introduced to the concept of gender diversity management.

CAADP: Agricultural Technical Vocational Education and Training (ATVET) for Women in Africa

The project aims to ensure that labour market-oriented, income-boosting training opportunities for women in the agri-food sector are taken up in the TVET systems in the selected pilot countries Kenya, Malawi, Ghana, Benin, Burkina Faso and Togo.

The training improves women’s access to formal and informal education in the agri-food sector and gives them the skills to earn a living through employment or self-employment. In the six partner countries the project targets women in formal vocational training, female smallholders who lack access to training and women who run small or micro businesses. The approach takes women’s diverse needs and social roles into account. As a priority, it therefore offers access to informal and flexible training options, such as evening and weekend courses. Furthermore, mentoring programmes are offered and teaching methods that are suited to women with little experience of attending school are promoted.

Strong in the work place – Migrant mothers get on board

With the ESF-programme "Strong in the work place – Migrant mothers get on board" the German government aims to enable mothers with a migrant background to sustainably secure their livelihoods. Women receive individual support on their path towards employment, and access to existing labour market integration services is improved. Since February 2015, around 80 project locations throughout Germany have been funded. The projects pursue both target-group-specific and structure-related approaches. In addition to targeted awareness-raising measures aimed at activating these women, the aim is also to raise business awareness of the potential of mothers with a migration background.

Italy

The Italian Development Cooperation (IDC) has always placed gender equality and women’s empowerment (GEWE) at the core of its policies and actions. Italy promoted GEWE by adopting a multidimensional and holistic approach: not only recognizing it as a fundamental condition to fulfill women’s human rights, but also unleashing women’s agency through transformative strategies for poverty eradication.

Women's social and economic empowerment, in fact, is key to women's ability to enjoy all other human rights, while recognizing the deep connection of the economic dimension to other sectoral dimensions.

Italy advocated for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls to be a stand-alone goal on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDG5), as well as a transversal component of the Agenda, and aligns its development actions with relevant International Bodies’ recommendations (i.e. UN, EU, G7 and G20).

Dedicated guidelines of the Italian Development Cooperation were adopted to translate into practice the promotion of the full participation of women in the socio-economic-development processes of partner countries. This is also reflected in the three-Year Programming and Policies Planning Document (PPPD) 2016–2018 and 2017–2019 of the IDC. The review of the IDC guidelines on gender equality and women’s empowerment is on-going and it will strengthen the methodology for the gender mainstreaming and its application in all the IDC activities, in line with the Agenda 2030 and its Sustainable Development Goals.

The Italian Strategy is based on a twin-track approach pursued over many years, while respecting national sectoral plans and policies of partner countries:

- The gender mainstreaming approach to be applied in all development activities;

- The implementation of dedicated project initiatives in favour of girls and women.

This IDC action follows a multidimensional and intersectoral focus where the complexity of women’s life and all discriminations, barriers and obstacles affecting their empowerment process are fully recognized and addressed. Furthermore, most IDC initiatives include the improvement of sex-disaggregated data collection systems and the implementation of gender budgeting. This ensures that women’s multidimensional well-being and the contribution of their unpaid work to the macroeconomic policy are taken into account in policy-making process at both local and national levels.

Italy also works with international organizations and recently new multilateral initiatives have been undertaken with UN Women, UNFPA, CIHEAM-IAMB, IOM, UNIDO and FAO.

IDC’s gender work in Senegal and Ethiopia, as well as the humanitarian initiative for Syrian women, are three relevant examples of this approach.

The bilateral Integrated Programme of Economic and Social Development in Senegal contributes to addressing the needs of women and vulnerable groups, in partnership with the Ministry of Gender Affairs, local institutions and civil-society organizations, while pursuing SDG 5 targets. By identifying women’s economic and social potential, and their needs, as well as gender barriers and discrimination, the initiative promotes women’s economic empowerment and agency through three components: 1. Promotion of access to economic resources and opportunities including jobs, financial specific services, property and other productive assets, skills development and market information; 2. Implementation of the Senegalese Gender-Based Violence strategy (prevention, support for survivors and their families, and promotion of responsive legal and justice systems); 3. Strengthen women’s participation and voice in the political decision-making process, including supporting women’s negotiating capacities, strengthening women’s entrepreneurial networks, promoting gender-sensitive budgeting and creating two Local Economic Development Agencies for women’s empowerment.

Women Economic Empowerment and Social Integration Project in Ethiopia. This bilateral pilot initiative aims at the integrated empowerment of socially and economically vulnerable women (women inmates, victims of trafficking, schoolgirls who reject harmful traditional practices) and promotes gender mainstreaming at the governmental level. It fosters the protection of the rights of women and girls at the community level, including through awareness-raising actions, while increasing the reporting on harmful practices and facilitating greater acceptance of women as entrepreneurs and leaders. Three pillars articulate this project: 1. Research and Gender Analysis focused on the women/girls’ voice approach to enhance their participation in the definition of gender-sensitive initiatives; 2. Capacity and knowledge building at institutional and community levels on gender roles and women’s rights to promote attitude change; 3. Economic empowerment to promote entrepreneurial skills, self-esteem and micro enterprises.

The new multi-bilateral initiative Assistance To and Empowerment of Syrian Refugee Women and girls and vulnerable women and girls of Host Communities in Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon is part of the IDC’s response to the Syrian crisis, with the main goal of improving the living conditions of Syrian refugee women and girls, while also providing them with opportunities to acquire the skills and expertise needed to rebuild their lives after returning to Syria. The economic-empowerment component is combined with reproductive and sexual health, and GBV response components. The participation of Syrian refugee women in peace negotiations and future reconstruction of this country is also promoted.

Italy has also actively advanced gender equality and women’s empowerment at the domestic level. Legal reforms and dedicated assistance frameworks are in place, including the promotion of social and economic integration of migrant women and girls. The Department of Equal Opportunities of the Italian Presidency of the Council of Ministers has launched – pursuant the first National Action Plan against Trafficking and Serious Exploitation of Human Beings (2016) – two annual calls for proposal to fund assistance projects for victims of human trafficking, including women and girls (for a total of €37 million in the biennium). Furthermore, the protection and empowerment of migrant women and girls are also considered by the National Strategic Plan on Male Violence against Women 2017–2020.

Japan

Creating a society where all women can shine has been one of Japan’s priority issues and various policies have been implemented toward achieving this goal. Under Prime Minister Abe’s initiative, Japan has strongly promoted international cooperation for gender equality and women’s empowerment with the belief that creating "a society where women shine" will bring vigour to the world.

In May 2016, Japan launched the Development Strategy for Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment as one of its thematic policies under the Development Cooperation Charter. The Strategy focuses on 1) promoting women’s and girl’s rights, 2) improving an enabling environment for women and girls to reach their full potential, and 3) advancing women’s leadership in politics, the economy and other public fields. On the occasion of the G7 Ise-Shima Summit (May 2016), Japan announced its plan to train approximately 5,000 female administrative officers and assist the education of approximately 50,000 female students over the three-year period of 2016–18.

Moreover, at the World Assembly for Women: WAW! 2016 (December 2016) that Japan has hosted since 2014 to create “a society where women shine” both in Japan and beyond, inviting top leaders from around the globe, Prime Minister Abe announced more than US$3 billion in total assistance for women in developing countries by 2018. These initiatives are steadily being implemented.

As part of these initiatives, Japan has implemented various projects to promote women’s economic empowerment, such as the African women's business-development seminar, capacity building and policy dialogue on catalyzing women entrepreneurship in Malaysia, capacity development of women’s union in support of gender-sensitive inclusive finance in Vietnam, and smallholder horticulture empowerment and promotion in Kenya, Tanzania, Madagascar, Palestine and Egypt.

Japan also supports women entrepreneurs in developing countries through its contribution to the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative (We-Fi) launched at G20 Hamburg summit in 2017.

Japan is one of the top donor countries to UN Women and contributed around US$22 million to UN Women projects in Africa and the Middle East regions in 2017. Especially, Japan supports the “Women’s Leadership, Empowerment, Access & Protection in Crisis Response (LEAP)” programme. LEAP provides a comprehensive response to the urgent needs of women in crisis situations, including protection from sexual violence and promotion of women’s participation. Japan, as a champion of LEAP, co-hosted the high-level LEAP roundtable with UN Women in New York City in March, 2018. Prime Minister Abe is selected as one of the 10 Heads of State in the UN Women “HeForShe Campaign” for encouraging the engagement of men and boys in the promotion of gender equality.

Japan is also one of the leading contributors to the office of the Special Representative of the Secretary General (SRSG) against Sexual Violence in Conflict and supports a number of projects to enhance response capabilities against sexual violence in such countries as Somalia, Congo Republic and Iraq. Japan formulated its “National Action Plan” on the UNSCR 1325 in September 2015 and has steadily implemented it.

Also, Japan has supported initiatives in sexual and reproductive health and rights for approximately 50 years through contributions to UNFPA and IPPF to empower women and girls all over the world. These initiatives include the provision of sexual and reproductive-health services, prenatal checkups, emergency obstetric care and Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP), as well as outreach activities through mobile clinics. Health is the basis for women’s and girls’ economic and political empowerment. Japan promotes universal health coverage (UHC) to enable women and girls to better protect their physical and mental health by accessing essential services. In December 2017, Japan co-hosted UHC Forum 2017 with World Bank, WHO, UNICEF, UHC 2030 and JICA to actively discuss the promotion of UHC internationally. More than 600 people attended the Forum in Tokyo.

Japan is also committed to make every effort both domestically and internationally to achieve the SDGs, and considers gender equality vital to achieving these goals. In May 2016, Japan established the “SDGs Promotion Headquarters” that is led by Prime Minister Abe and consists of all Ministers. The Headquarters formulated the “SDGs Implementation Guiding Principles” in December 2016, along with the “SDGs Action Plan 2018” in December 2017, which includes “empowerment of next generations and women” as one of its three pillars.

United Kingdom

Women’s economic empowerment is central to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals and as such, is a key component of the UK Department for International Development’s (DFID’s) approaches to both economic development and gender equality.

DFID’s Economic Development Strategy (launched in early 2017) seeks to transform economies and ensure that growth delivers for everyone. Long-term change will come from more-productive jobs with higher pay and better working conditions. This means moving into higher- productivity sectors such as manufacturing and boosting productivity within existing sectors such as agriculture. Trade, increased investment and private-sector growth, will all be critical to creating more and better jobs. Barriers need to come down so that opportunities are more fairly distributed and no one is left behind.

The strategy commits to ensuring that: all economic-development work addresses gender discrimination, with a focus on better jobs in high-growth sectors; increasing returns from, and improving conditions in, the sectors where women already work; and removing gender-specific barriers to opportunities, including access to assets, time poverty, and discriminatory laws and norms.

DFID’s Strategic Vision for Gender Equality (launched in 2018) commits to continued leadership and to investment in the four foundations where DFID has a track record, building on results achieved to date and taking them to scale:

- Ending all forms of violence against women and girls

- Universal sexual and reproductive health and rights

- Girls’ education

- Women’s economic empowerment and inclusive growth

DFID will also use its expertise and networks to step up leadership on a fifth foundation – women’s political empowerment – which, delivered together with the above four, will transform the lives of girls and women.

DFID will support girls and women to be economically empowered through better access to, and choice over, jobs in high-growth sectors with improved working conditions; and better access to digital, financial, land and property assets. The UK will address the gender-specific barriers to both, including the laws and social norms that adversely affect women, e.g. the unequal burden of unpaid care work, harassment, violence and discrimination. This approach builds on the conclusions of the UN Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Women’s Economic Empowerment (2016 and 2017), which the UK Government was proud to support.

Examples of DFID’s innovative approach to the economic empowerment of women and girls are set out below:

Work and Opportunities for Women (WOW): Will work with global and British business to provide 300,000 women with improved access to better jobs in supply chains in agriculture, manufacturing or other global sectors.

SPRING – Assets to Adolescent Girls Programme: (A joint programme with USAID and DFAT). A business accelerator supporting businesses to reach adolescent girls with products and services to help girls learn, earn, save and stay safe.

Ethiopia Land Investment for Transformation: Support to the Government of Ethiopia in the provision of map-based land certificates to farmers in four regions. The project aims to secure land ownership for 6.1 million households and to implement a second-level land certification process to register 14 million parcels of rural land, with 70 percent of holders being women, either jointly or individually.

DFID will continue to equip its staff and delivery partners with the skills, tools and knowledge to better integrate gender equality into policies and programmes, and to join up across sectors to take a gender-equality portfolio approach. This will include embedding gender equality more fully into business systems to ensure more-effective delivery, tracking of expenditures and results, and greater accountability to the women and girls whose lives we are seeking to change, and to the UK taxpayer, for delivery on the ground.

United States of America

The United States is resolute in its commitment to promote women’s economic empowerment as a fundamental component of U.S. foreign policy. As stated in President Trump’s 2017 National Security Strategy, “Societies that empower women to participate fully in civic and economic life are more prosperous and peaceful.”

When women are empowered economically, they invest back into their families and communities, producing a multiplier effect that spurs economic growth and creates more peaceful societies. Accelerating women’s economic empowerment around the world is also integral to supporting developing countries to achieve economic self-reliance and enabling women to realize their own economic aspirations.

In practice, the United States recognizes that women’s economic empowerment requires simultaneously addressing complex constraints, challenges and opportunities. This requires a multi-pronged approach to address the many facets of this problem. In broad terms, the United States works to:

- Reduce disparities in women’s access to, control over, and benefit from resources, wealth, opportunities, and services – whether economic, social, political, or cultural;

- Prevent and respond to gender-based violence, and sexual exploitation and abuse and their harmful effects on individuals, communities, and nations; and,

- Develop the capabilities of women and girls to realize their rights, determine their life outcomes, and influence decision-making in households, communities, and societies.

The United States implements its National Security Strategy through programs that enable women and girls to obtain the skills, means, and opportunities to realize their economic potential. These efforts follow three, inter-linked, reinforcing pillars: workforce-development and skills-training; entrepreneurship and access to capital; and improvements in the enabling environment, including laws, regulations, policies, and social and cultural norms.

Workforce development and skills-training for women and girls help pave the way for economic empowerment. Improving women’s and girls’ access to quality education and training, including training opportunities closely linked with employer needs, can lead to higher-paying jobs, including in high-growth, in-demand occupations, such as those in the STEM fields. Moreover, the United States is working to close the gender digital divide through programs such as WomenConnect, an effort to enable women’s equal access to digital services that provide tools for entrepreneurship, access to education and life-enhancing information.

Women entrepreneurs are an emerging market force, and serve as an important source of innovation and job creation. The United States will continue to support women who want to start and scale their businesses, to create prosperity and stability for their families, communities, and countries. For this reason, the United States co-hosted with India the 2017 Global Entrepreneurship Summit to focus specifically on women’s entrepreneurship.

Women’s equal access to the capital and networks to fund and expand their businesses is fundamental to the success of women entrepreneurs in emerging markets. Through activities like the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative, the United States is mobilizing financing to improve access to capital, provide technical assistance, and invest in women-owned businesses in emerging markets. Through its development finance activities, the United States also supports businesses owned and run by women, as well as businesses that enhance women’s economic participation and access through their policies and practices, as well as their products and services.

Changes to discriminatory laws, policies and norms are important drivers of women’s economic empowerment. The United States assists development partners to identify and reduce the policy, legal, and regulatory barriers to women’s participation in the economy and promote women’s economic empowerment.

European Union

The EU has a strong internal and external policy related to gender equality and women’s empowerment.

Internally, the Commission adopted legislative proposals for improving work-life balance for working parents and caregivers; an Action Plan to close the gender pay gap; and a quota of 40% for the under- represented sex on companies’ executive boards. In the meantime, the Commission is leading by example, aiming at reaching the same target by the end of its current mandate (2019). In 2017, women were the 37% of the middle and senior managers.

The European Consensus on Development places gender equality at the core of the EU’s values, and identifies women as agents of development and change. With the Consensus, the EU and its Member States committed to promote women's and girl’s economic and social rights, as well as their empowerment. In the EU Global Strategy, gender equality and women's empowerment are indicated as cross- cutting priories for all polices. And finally, the II EU Gender Action Plan (2016–2020) - GAP II identifies Women's Economic Empowerment (WEE) as a central pillar of the EU's strategy to close the gender gap and to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

In particular, the so-called GAP II sets specific objectives and targets to be reached by 2020. One objective is to mainstream gender actions across 85% of all new initiatives. The target is not reached yet, but progress is undeniable: an average of about 65% of all initiatives adopted in 2017 mainly or significantly aim to promote gender equality and/or women’s empowerment, compared with averages of 47.3% in 2015 and 58.8% in 2016.

Gender analysis became mandatory for informing the design of all new initiatives and clear top-level support is ensured for implementation of GAP II.

Finally, many initiatives are taken to keep women’s rights at the top of the international agenda. The most recent one is the EU-UN Spotlight Initiative, which steers a significant amount of funds toward combating violence against women and girls. Backed by their initial contribution of 500 million euros, Spotlight will focus on particular forms of VAWG that are prevalent or prominently emerge in specific regions, such as femicide in Latin America; trafficking in human beings and sexual and economic (forced labour) exploitation in Asia; sexual and gender-based violence and harmful practices in Africa; specific forms of domestic violence in the Pacific and the Caribbean regions. The Spotlight Initiative will work closely with civil society, UN agencies and governments to provide comprehensive, high-quality interventions that can save women and girls’ lives. Our ambition is to see this initiative being transformational for the lives of women and girls worldwide, in particular for young people and those living in the most marginalised and vulnerable situations. A special focus will be put on reaching women and girls that are most at risk of violence and whom traditional programmes do not reach leaving no one behind.

Regarding WEE, the EU supports several programmes and projects at the regional and national levels:

- The External Investment Plan (EIP) promotes gender equality and empowerment of women, providing opportunities for them in all five investment windows (sustainable agriculture, sustainable energy and connectivity, micro small and medium enterprises, digital for development and sustainable cities). Moreover, the third pillar of the EIP aims to promote a conducive investment climate through a structured dialogue with the private sector, and gender-policy reform is one of the thematic to cover.

- Several projects on sustainable value-chains in the garment sector (dominated by women – 75% of workforce) as examples: 1) The action "Promoting responsible value chains in the garment sector" (€19 million), which supports ILO on child and forced labour in cotton supply chains, the G7 Vision Zero Fund on occupational health and safety, and a call for proposal on transparency and traceability in the garment sector. 2) The partnership with the International Trade Center (ITC) to strengthen fashion value-chains and boost job creation in Burkina Faso and Mali. 3) Within the SWITCH Africa program, the Green Tanning Initiative focuses on environmental sustainability in the leather industry in Ethiopia.

- Women and entrepreneurship: The DG DEVCO of the European Commission is finalizing a €10 million project that aims to promote women's economic empowerment and financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan countries. The specific objective is to promote women's economic empowerment and financial inclusion through improved access to financial products and services, and access to essential critical skills and capacity-building services, and decent jobs.

- Women and Sustainable Energy: The Commission has also developed the Electrification Financing Initiative (ElectriFI), a €115-million programme promoting access to energy in developing countries by stimulating the private sector (including women-lead businesses) and mobilizing financiers. Gender-related issues form an integral part of the programmes, including the promotion of women's businesses and/or women as end beneficiaries. The EU has also finalised the evaluation of the €20 million call for proposals for projects that foster women's entrepreneurship in the sustainable-energy sector. Three projects have been selected that will contribute to sustainable energy promotion and gender equality.

- Women and agriculture: A €5 million project is being finalized that aims to promote gender-transformative approaches in rural areas. The project focuses on removing structural, legal and institutional barriers to gender equality in agriculture value-chains.

The EU is supporting multi-stakeholders dialogue and private-sector engagement for women's economic empowerment through responsible business conducts with two projects during 2018–2021: one targets G7 countries and one targets Latin American countries.

Moreover, the EU Strategic engagement for gender equality 2016–2019 focuses on priorities including: increasing female labour-market participation and equal economic independence; reducing the gender pay, earnings and pension gaps; and promoting equality between women and men in decision-making.

The EU enshrines the issue of women’s economic empowerment in its process of economic-policy coordination among Member States. The 2018 Annual Growth Survey further called for more measures to foster work-life balance, noting that they are crucial to gender equality and to increased female labour-market participation.

The EU also supports projects strengthening gender equality and rewards inspiring initiatives that could be replicated across Europe. For instance, through the EU Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme, the EU helps to finance projects to incentivize the equal economic independence of women and men.

Recent policy initiatives to strengthen women’s economic independence and empowerment:

- In April 2017 the Commission adopted, in the context of the European Pillar of Social Rights, the initiative on work-life balance for working parents and careers. The initiative is a comprehensive package of policy and legal measures, including a proposal for a Directive to modernize EU legislation on family-related leave and flexible working arrangements.

- On 20 November 2017, the Commission adopted the 2017–2019 Action Plan to tackle the gender pay gap. It comprises a broad and coherent set of 20 actions to be delivered during the next two years.

2.2 Funding for Women’s Economic Empowerment

This section presents official development assistance (ODA) disbursements by G7 countries and the European Union (EU) in their efforts to implement the 2015 Elmau commitment to “support our partners in developing countries and within our own countries to overcome discrimination, sexual harassment, violence against women and girls and other cultural, social, economic and legal barriers to women’s economic participation.” To track progress against this commitment, the Accountability Working Group has identified two indicators: the first indicator measures G7 and EU support that directly enables women’s economic participation; and, the second indicator focuses on the elimination of violence against women.

To measure economic support to gender equality and women’s economic empowerment, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) uses the Development Assistance Committee’s (DAC) gender equality policy marker. It is a qualitative statistical tool used to record aid activities that target gender equality as a principal or significant objective in economic and productive sectors and in enabling sectors such as education and training.Footnote iii

In 2015 and 2016, G7 members and the EU dedicated 28%, of their total ODA disbursements towards projects or programmes with a strong commitment towards women’s economic empowerment. Please refer to Table 1.

The second indicator focuses on support for women and girls to overcome violence.Footnote iv In 2015 and 2016, combined, G7 members and the EU dedicated over US$ 529 million towards mitigating violence against women. Please refer to Table 2.

The table below shows each donor's ODA gross disbursements in US$ millions, dedicated to economic-growth-related initiatives focused on achieving gender equality and women's empowerment as a percentage of total ODA screened. ODA screened represents the percentage of each donor’s funds that are focussed on women and girls. This is measured by drawing on OECD-DAC data to determine the proportion of gender-targeted ODA spent on economic and productive sectors. The economic and productive sectors assessed align with those used by the OECD-DAC Network on Gender Equality in its reporting (see Data Source). Sectors that support and enable women’s economic empowerment, such as those related to education and training, are also included.

| Donor | Principal* | Significant** | Screened, not targeted*** |

|---|---|---|---|

| * Principal means that gender equality is the main objective of the project/programme and is fundamental to its design and expected results. The project/programme would not have been undertaken without this objective. ** Significant means that gender equality is an important and deliberate objective, but not the principal reason for undertaking the project/programme. *** Total screened is the total of projects/programmes screened against the gender equality policy marker and marked as not targeted. | |||

| Canada | 12.00 | 334.88 | 106.05 |

| France | 1.64 | 557.97 | 1,791.27 |

| Germany | 13.89 | 1,553.54 | 3,539.12 |

| Italy | 3.11 | 81.85 | 121.24 |

| Japan | 7.34 | 936.84 | 4,965.93 |

| United Kingdom | 93.29 | 900.73 | 1,355.75 |

| United States | 162.12 | 881.84 | 1,991.68 |

| EU Institutions | 35.62 | 694.92 | 2,128.83 |

| Total (in US$ millions) | 329.01 | 5,942.58 | 15,999.85 |

| 28% | |||

| Donor | Principal* | Significant** | Screened, not targeted*** |

|---|---|---|---|

| * Principal means that gender equality is the main objective of the project/programme and is fundamental to its design and expected results. The project/programme would not have been undertaken without this objective. ** Significant means that gender equality is an important and deliberate objective, but not the principal reason for undertaking the project/programme. *** Total screened is the total of projects/programmes screened against the gender equality policy marker and marked as not targeted. v Between 2015 and 2016 there was a slight change in EU’s methodology to report all the markers of the EIB (extending agency 3) transactions to OECD. In 2015 the gender marker of EIB transactions was reported empty, meaning not screened, and in 2016 the gender marker of EIB transactions was reported with the value '0', meaning not targeted. | |||

| Canada | 8.56 | 387.20 | 105.45 |

| France | 14.74 | 399.69 | 1,847.26 |

| Germany | 16.22 | 1,405.45 | 3,310.37 |

| Italy | 2.35 | 76.17 | 70.90 |

| Japan | 5.50 | 1,706.38 | 4,885.80 |

| United Kingdom | 61.24 | 1,192.99 | 1,172.57 |

| United States | 412.05 | 989.62 | 1,579.22 |

| EU Institutions | 56.33v | 1,249.56 | 7,373.13 |

| Total (in US$ millions) | 577.38 | 7,464.75 | 20,344.71 |

| 28% | |||

Data source: OECD DAC-CRS Aid Activities Database

Transport and storage (purpose code 210), Communications (purpose code 220), Energy generation, distribution and efficiency (purpose code 230), Energy generation, distribution and efficiency – general (purpose code 231), Energy generation, renewable sources (purpose code 232), Energy generation , non-renewable sources (purpose code 233), Hybrid energy electric power plants (purpose code 234), Nuclear energy electric power plants (purpose code 235), Heating, cooling and energy distribution (purpose code 236), Banking and financial services (purpose code 240), Business and other services (purpose code 250), Agriculture (purpose code 311), Forestry (purpose code 312), Fishing (purpose code 313), Industry (purpose code 321), Mineral resources and mining (purpose code 322), Construction (purpose code 323), Trade policy and regulations and trade-related adjustment (purpose code 331), Tourism (purpose code 332), Urban development and management (purpose code 43030), Rural development (purpose code 43040), Secondary education (purpose code 113), Post-secondary education (purpose code 114), Medical education/training (purpose code 12181), Health personnel development (purpose code 12281), Education and training in water supply and sanitation (purpose code 14081), Environmental education/training (purpose code 41081), and Multisector education/training (purpose code 43081).

| Donor | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vi According to the Law n. 125 as of 11.8.2014, the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation was established January 1st, 2016. During that year, delivery capacity of programmatic activities was delayed due to new operational arrangements and mechanisms required by the law that had to be put in place. vii For self-reporting (2015 data and a part of 2016 data), Japan relied on ODA total disbursements of the projects sorted from the list of cases reported in the implementation status report in the Annual Report on the National Action Plan on Women Peace and Security. viii Total only includes principle VAWG programmes. The UK also has over 100 significant programmes contributing to VAWG outcomes. | |||

| Canada | 16.84 | 18.16 | |

| France | 0.45 | 3.54 | |

| Germany | 21.23 | 17.05 | |

| Italyvi | 15. 80 | 5.93 | |

| Japanvii | 33.03 | 45.86 | |

| United Kingdomviii | 44.63 | 62.61 | |

| United States | 98.4 | 108.7 | |

| EU Institutions | 20.02 | 17.21 | |

| Total (in US$ millions) | 250.4 | 279.06 | |

To establish the baseline figures for indicator 2, G7 members used the following methodological approaches:

- Self-reporting for projects addressing violence against women for 2015 and 2016; and,

- A combination of self-reporting and the Creditor Reporting System (CRS) purpose code 15180 - Violence against women as reported to the OECD-DAC for 2016.

Chapter 3 - Making Strides in Women’s Economic Empowerment: G7 Initiatives

Snapshot

- Making strides in women’s economic empowerment requires a multidimensional lifecycle approach that addresses constraints and fosters an enabling environment where women can succeed.

- Investing in women’s and girls’ health, education, skills development, employment and entrepreneurship help women realize their full potential. It is also an investment in sustainable, inclusive economic growth and the well-being of families and communities worldwide.

- Improving access to economic and productive sectors and overcoming cultural, social and legal barriers are essential to strengthening women’s economic participation.

- Advancing women’s agency increases their ability to assert their needs, aspirations and economic independence, and empowers them to participate in decision-making and influence the policies and programs that affect their lives.

G7 members have undertaken initiatives in seven action areas that are critical for strengthening women’s economic empowerment. These areas demonstrate measures adopted to improve women’s access to critical productive resources and opportunities, while overcoming key barriers to their full and equal participation in the economy. Focus is given to women’s voice and leadership because women’s political participation is linked to broader economic empowerment outcomes.

3.1 - Improving Access to Economic and Productive Sectors for Women’s Economic Empowerment

a. Inclusive Markets, Trade and Entrepreneurship

There is evidence that increasing women’s access to inclusive markets and global supply-chains yields important benefits in terms of women’s economic empowerment. Women’s labour-force participation and entrepreneurship, and their ability to sustain and grow businesses, lead to faster rates of economic growth and substantive equality for women. To enhance trade and entrepreneurship opportunities for women, it is necessary to prioritize women’s access to financial and business development services.

Women are less likely than men to own formal enterprises; only 30-37% of small and medium-sized enterprises in emerging markets are owned by women.Footnote 13 Studies reveal that women face a nearly US$300 billion credit gap when it comes to accessing financing, which stymies their ability to start or scale-up business ventures. Women entrepreneurs are also disproportionately represented in low-productivity, growth-limited sectors, which curtails their ability to expand their operations and personal incomes. For example, only 14-19% of International Financial Corporation loans are issued to women-owned small and medium enterprises, even though evidence shows that these enterprises perform just as well as those owned by men.Footnote 14 Furthermore, a study from across 20 countries (in five regions of the world) found that women’s businesses were less likely to be engaged in international trade than those businesses owned by men.Footnote 15

The G7 recognizes that gender gaps across sectors and industries leads to economic losses. It has therefore prioritized advancing trade by committing to align aid for trade with the needs of developing- country partners, and by providing technical assistance and capacity building that facilitates trade. This link between women’s economic empowerment and improved trade opportunities has been recognized in the Addis Ababa Agenda of ActionFootnote 16 and in the 2030 Agenda.Footnote 17 The G7 Leaders’ Declaration at the 2016 Ise-Shima Summit also committed to working with relevant stakeholders to promote quality infrastructure investments, responsible supply chains, and greater transparency in these and other efforts.Footnote 18 These commitments contribute to the G7’s work to enhance the economic participation of women.

Germany

Supporting women entrepreneurs in starting and growing their businesses

Worldwide, fewer women than men own enterprises: only 30% of formal small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) around the world are owned and run by women. In developing countries, women often face legal, social and financial barriers to start or grow a business. 70% of formal women-owned SMEs in developing countries are either shut out of financial institutions or can’t get the capital they need.

Germany is highly committed to the economic empowerment of women. Therefore, Germany and the US jointly initiated the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative (We-Fi), which was endorsed by G20 at the Hamburg Summit in 2017. The Fund is anchored at the World Bank and supports women entrepreneurs worldwide in starting and growing their businesses.

The 14 founding donors committed more than US$340 million to the We-Fi. Five are G7 members (Germany, US, Japan, Canada and the United Kingdom) and have pledged more than half of the total amount. The goal of the initiative is to leverage this amount and mobilize more than US$1 billion in additional financing from international financial institutions and commercial financing.