Pandemic brings a crisis of care for women

Working on a report on the care burden borne by women and girls in developing countries, Melani O’Leary knows well how unpaid work affects women’s nutrition, health, education levels and livelihoods in such contexts. But she doesn’t have to look far to find parallels at home—or to see how the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the amount of domestic labour done by women everywhere.

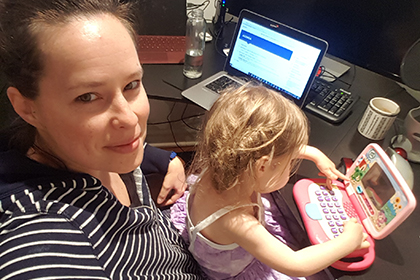

Melani O’Leary does her job as a health technical specialist for World Vision Canada at home with her daughter, Trinity, on her lap.

O’Leary juggles her job as a health technical specialist for World Vision Canada with looking after her daughters Capri, 6, and Trinity, 3, while her family has remained at home in Toronto under the province’s shutdown orders.

“Even with a supportive husband, I still spend most of the day with 1 or both of my kids on my lap, while he gets much more undisturbed work time in his basement office,” she says. O’Leary appreciates that she can work remotely amid the global health crisis, but she feels the pressure of looking after her home and children. “It’s a struggle on both sides.”

She hears much the same lament from other women in the coalition of organizations developing a new framework to prevent malnutrition. The initiative looks at how gender roles and responsibilities, such as unpaid care work, trap women and girls around the world in a cycle of malnutrition, poverty and unmet potential.

COVID-19 has exacerbated the problem, the group has found, undoing decades of progress in giving women and girls access to nutrition and other essential services and possibly “changing the trajectories of their lives forever.”

The pandemic has brought to light the essential role of women as unpaid and paid care-providers and its effect on their well-being and economic prospects. Women globally perform about 3/4 of domestic duties, and while unpaid workloads have increased for all under COVID-19, women are taking on a greater intensity of care-related tasks and are leaving the work force more than men, according to a report titled Whose time to care? by UN Women. A study titled Care in the time of coronavirus, carried out by Oxfam in Canada, the United States, Britain, the Philippines and Kenya, found that almost half of women are feeling more anxious, depressed, overworked, isolated or physically ill because of the increased domestic workload stemming from pandemic containment measures. And Gender Inequality and the COVID-19 Crisis: A Human Development Perspective, a working paper by the United Nations Development Programme, shows that women have less capacity to absorb economic downturns from COVID-19. That is because women have lower earnings, savings and job security, and they are over-represented in informal employment, especially in developing economies.

Programs supported by Canada are addressing unpaid care work, informal employment and frontline roles for women and girls as they exacerbate gender inequality in developing societies around the world. And these efforts have been heightened to tackle the deepening crisis of care brought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

A ripple effect

Through Born on Time, a program of World Vision Canada, Save the Children Canada and Plan International Canada in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Mali, O’Leary sees the problem that their role as caregivers poses for women and girls. “It creates a ripple effect across their entire life,” she says. A vicious cycle can emerge: Women have no access to education or skills, and face constraints to engaging in even low-paid work, which diminishes their voice, value and decision-making opportunities within the household. It also further exposes them to harmful practices such as gender-based violence and child marriage.

O’Leary notes that women and girls are also more vulnerable, both directly and indirectly, to crises. “When you introduce another shock like COVID, it can really unhinge the delicate ecosystem that they’re already operating in,” she explains. “The impact of the pandemic on women and girls is so much more devastating than it is for men.”

Born on Time, which is supported by Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and Johnson & Johnson, helps women and girls recognize and act on their own power, O’Leary says. “It makes them the change agents they should be.”

The program helps women and adolescent girls to better understand their reproductive and sexual-health rights, as they also learn to make decisions about their nutrition and self-care. It also works with local women’s groups to establish revolving loan funds that women can use to pay for critical needs like medical appointments. This brings improved health outcomes, increasing the chances of women having healthy pregnancies and babies being born on time. Messaging on billboards and in radio spots targets gender stereotypes and risky behaviours, which reinforces efforts to lower rates of gender-based violence and early marriage, O’Leary says. The program also encourages men to take on more child-care and domestic chores, which has “shifted the power dynamics in households, a transformation that is much needed during the pandemic,” she comments.

A focus on fathers

A man helps his wife draw water from a well in Bangladesh. Photo: Plan International Bangladesh

Engaging men is a core strategy implemented in a gender-transformative project by Plan International Canada called Strengthening Health Outcomes for Women and Children (SHOW). It sets up “fathers’ clubs” that encourage “positive masculinities,” helping men to broaden their understanding of gender equality. This includes the need to protect and promote the health and well-being of their partners and children, as well as fostering a more equitable division of household labour.

Saadya Hamdani, director of gender equality for Plan, says the program has been ramped up through pandemic-response funding from GAC to deal with the impact of COVID-19 in Bangladesh, Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal. She notes that issues such as school closures, the need to fetch additional water, hygiene and sanitation duties as well as care for children, family elders and the sick, have resulted in time poverty, physical and emotional “unwell-being” for women and girls “and a retrenching of gender inequality.”

A member of a fathers’ club in Nigeria with his child. Photo: Plan International Nigeria

SHOW has pivoted to address this added care burden through targeted discussions in the fathers’ clubs. These now meet virtually, for example by using the WhatsApp platform online, with support from the program to pay for the devices themselves or extra data required. It also conducts outreach among community leaders and women’s groups to shift attitudes about cultural norms surrounding matters like household decision-making and conflict resolution, Hamdani says.

The program additionally encourages support for front-line workers—predominantly women—engaged in paid and volunteer health-care tasks, which have “gone up exponentially.” These jobs are often stigmatized, because they involve potential exposure to the virus, and the women also face the burden of unpaid care work at home, Hamdani adds.

Improving employment levels

Samar Omar works as a medical office assistant. Photo: Dima Al-Qutub

In Jordan, a project called Women’s Economic Linkages and Employment Development (WE LEAD), financed by GAC and implemented by a joint consortium that includes World University Service of Canada and Canadian Leaders in International Consulting, is working to enhance women’s empowerment by increasing the employment of women in the health-care sector. It does this by reducing gender-specific barriers in areas such as childcare, transportation, safe work environments and social norms.

The project works with national partners to provide vocational training and internships for women like Samar Omar, a mother of 5 who was able to get a job as a medical office assistant at a Jordanian hospital through WE LEAD. With the money she earns there, Omar contributes to her household living expenses, sends her children to school and has bought a family car. “After this experience, I will definitely encourage my children, particularly my daughters, to work and be independent,” she says.

WE LEAD also supported the establishment of a nursery at another hospital, which was a benefit to Rawand Laith after she had a baby. Staff turnover and absences at the hospital dropped once the daycare became available.

Rawia Na’oum, a gender-equality specialist with WE LEAD, says while the women have made strides as working mothers, when the pandemic hit, they were among the hospital employees who were let go for several months, because they had children to look after. WE LEAD is working to reverse this gender bias within the hospitals’ policies and practices. “It’s a long process to overcome these kinds of challenges,” says Na’oum, which she says requires interventions ranging from awareness-raising to policy changes. “We hope to have a positive impact.”

Women “left on the side”

Increasing employment opportunities for women is the focus of a project in Central America called Promoting Rural Economic Development for Women and Youth in the Lempa Region of Honduras (PROLEMPA). Evelyne Morin, a program manager at CARE Canada, says the goal is to improve the livelihoods of small entrepreneurs and producers, particularly women, youth and Indigenous people in the impoverished Dry Corridor of western Honduras. The program—which is being implemented in a consortium that includes CARE International, SOCODEVI, SAJE Montréal Centre, TechnoServe and CESO, as well as through the work of some 20 local partner organizations and institutions—supports the efforts of women to grow coffee and develop rural tourism. It also tries to increase women’s voices, decision-making power and meaningful participation in governance bodies there.

This is all challenging in the context of the COVID-19 lockdown measures and movement restrictions, Morin says. “Women have been left on the side.” Their businesses tend to be informal start-ups that have suffered, and women are less likely to use technology and get information about issues like pandemic mitigation efforts.

PROLEMPA helps by providing cell-phone credits as well as phones to women and community leaders to help them stay in touch with each other and learn about support programs. It offers food, hygiene kits and agricultural inputs like seeds and fertilizer. Advertisements and training raise awareness and warn about the risks of the unequal division of unpaid care work, educating men that “your wife is not the only one who should be doing domestic labour,” Morin says. Women in handicraft businesses have also been supported to switch to making facemasks or to grow and sell vegetables with the support of the program, she adds.

A dual purpose

In Kenya, a COVID-19 prevention measure focused on teaching women to make soap in West Pokot County in the country’s central Rift Valley region has turned into an important money-making venture. The enterprise falls under GAC’s pandemic funding support for the Enhancing Nutrition Services to Improve Maternal and Child Health in Africa and Asia (ENRICH) program established in Bangladesh, Kenya, Myanmar and Tanzania by World Vision Canada, Harvest Plus, Canadian Society for International Health and Nutrition International.

The Mbara Mothers Support Group in West Pokot County, Kenya, makes soap. Photo: ENRICH staff

Antonina Yona, 30, a mother of 4 who lives in the rural village of Tokorion, previously panned for meagre amounts of gold in the area’s muddy rivers from sunrise to sunset. Now she can stay at home and breastfeed her 2-month-old baby Methusela while she makes the soap, which “takes less time and the profits are good,” she says.

Like the other women in the Mbara Mothers Support Group, Yona spends some of the money she makes on nutritious food for her family. She’d like to invest in chickens for food and commercial production, and plans to use the money to grow vegetables and to pay school fees for her children.

Cleanliness has also greatly improved in Yona’s household and among her family members with their improved access to soap. Asrat Dibaba, chief of party for the ENRICH program, says that better hygiene is a long-term benefit of the new business in the region, where diarrheal infections among children and skin diseases are common. Another advantage is the fact that the women are learning to invest and save money, opening bank accounts and improving their standard of living.

With their communities hard hit by COVID-19 restrictions, the soap making “has a dual purpose” for the women, he says. “They have income, they control that income and that gives them a sense of power within the household and within their communities.”

A long way to go

Melani O’Leary of World Vision is encouraged by the success stories that have come about from programs like Born on Time, as well as the fact that the care burden is getting attention amid the COVID-19 crisis. But she’s worried about how the pandemic will affect women’s health and well-being in the years ahead.

“Where resources are pinched, women are going to fall at the bottom,” she says. Food shortages bring poor nutrition for women, making them more susceptible to COVID-19, and there are broader societal problems associated with the increased demand for caregiving.

“Even in Canada we have such a long way to go. Women are leaving the workforce, they’re cutting back hours, they’re abandoning leadership positions,” O’Leary allows. “We continue to see our voices diminished and to lose control over our bodies, our well-being and our futures.”

For the coalition that she’s a member of, there’s much work to be done to “operationalize” the gender-transformative nutrition framework so that it can help to prevent malnutrition in the developing world. But programming that alters problematic cultural norms is an important start, O’Leary adds. “We’ve given women some skills to be more resilient in the context of this pandemic.”

- Date Modified: