Evaluation of the Canadian Foreign Service Institute – FINAL REPORT

Global Affairs Canada

Office of The Inspector General

Evaluation Division

May 2016

Table of Contents

- Abbreviations, acryonyms and symbols

- Acknowledgements

- Executive summary

- 1.0 Introduction

- 1.1 Departmental Training Context

- 2.0 Evaluation Scope & Objectives

- 3.0 Evaluation Findings

- 3.1 Relevance Issue #1: Continued Need for the Program..

- 3.2 Relevance Issue #2: Alignment with Government Priorities

- 3.3 Relevance Issue #3: Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

- 3.4 Performance Issue #4: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

- 3.5 Performance Issue #5: Demonstration of Efficiency & Economy

- 5.0 Evaluation Findings on Performance of Training Models With OGDs

- 6.0 Conclusions of the Evaluation

- 7.0 Recommendations

- 8.0 Management Response And Action Plan

- Appendix 1: List of Findings

- Appendix 2: Functions of CFSI Centres

- Appendix 3: Evaluation Issues and Questions

- Appendix 4: List of Training Providers with GAC

- Appendix 5: Documents Reviewed

Abbreviations, acryonyms and symbols

- CBS

- Canada-Based Staff

- CFSC

- Centre for Intercultural Learning

- CFSD

- Centre of Learning for International Affairs and Management

- CFSI

- Canadian Foreign Service Institute

- CFSE

- Centre for Learning Advisory Services, eLearning and Administration

- CFO

- Chief Financial Officer

- CFSL

- Centre for Foreign Languages

- CFSS

- Centre for Corporate Services Learning

- CHRBP

- Common Human Resources Business Process

- CIDA

- Canadian International Development Agency

- CSPS

- Canada School of Public Service

- DFAIT

- Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade

- DFATD

- Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development

- DPR

- Departmental Performance Report

- DRAP

- Deficit Reduction Action Plan

- FSDP

- Foreign Service Development Program

- FTE

- Full-Time Equivalent

- GAC GL

- Global Affairs Canada General Ledger

- GoC

- Government of Canada

- HOM

- Head of Mission

- HRMS

- Human Resources Management System

- IMS

- Integrated Management System

- IPT

- Individual Professional Training

- IT

- Information Technology

- LES

- Locally-Engaged Staff

- LMS

- Learning Management System

- MAF

- Management Accountability Framework

- MCO

- Management and Consular Officer

- MOU

- Memorandum of Understanding

- OGD

- Other Government Department

- OLF

- Organizational Learning Fund

- PAA

- Program Alignment Architecture

- PSES

- Public Service Employment Survey

- ROI

- Return on Investment

- RPP

- Report on Plans and Priorities

- TB

- Treasury Board

- ZIE

- Evaluation Division, Office of the Inspector General

Acknowledgements

The Evaluation Division (ZIE), Office of the Inspector General, Global Affairs Canada (GAC), would like to thank all those individuals who shared their thoughts on the relevance and performance of the Canadian Foreign Service Institute (CFSI). ZIE also wishes to acknowledge the contribution of each of the CFSI centres in facilitating the generation of data in support of this evaluation.

Executive summary

Established in 1992, The Canadian Foreign Service Institute (CFSI) was tasked with the delivery of training to Foreign Service Officers. Since then, CFSI’s mandate has expanded and today it is responsible for offering continuous learning by providing training related to international affairs, professional and management development, corporate accountability, foreign languages and intercultural effectiveness.

In the 2012-2013 fiscal year, the former DFATD appropriation to CFSI was $15.3 million with Other Governmental Departments (OGDs) contributing an additional $3.2 million to CFSI for the provision of intercultural training. However, following the amalgamation with the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the majority of OGD contributions have ceased.

CFSI is responsible for implementing the government-wide Policy on Learning, Training and Development at GAC and advising on the development of individual and organizational learning plans. Organized into four centres of learning, CFSI’s clientele consists of nearly 10,000 employees, serving at headquarters and in more than 270 offices in 180 countries. CFSI offers extensive training to the Foreign Service, Canada-Based Staff (CBS), and Locally-Engaged Staff (LES). Training is delivered in-class, online, and through distance learning options, designed to support GAC’s leadership role in international affairs while providing learning opportunities to all occupational groups.

The last evaluation of CFSI was in 2007. Given the date of the previous evaluation, and given the expansion of services provided by CFSI with the amalgamation between CIDA and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT), it has become prudent to assess its continued relevance and performance within GAC. This evaluation covers the period between fiscal year 2010/2011 to 2014/2015.

Guided by an assessment of relevance and performance— as defined in the core issues of the 2009 Treasury Board (TB) Directive on the Evaluation Function— key informant interviews, focus groups, site visits, and a document review were carried out, with evidence interpreted and triangulated to determine client perceptions and experiences with CFSI, ultimately formulating this evaluation. This analysis was based on the data from 99 interviews and 30 program-related documents, in addition to documents containing financial and administrative dataFootnote 1 . The effectiveness and efficiency of CFSI training delivery vis-à-vis other departmental training providers was also assessed.

Overall, the evaluation found sufficient evidence to demonstrate that between 2010 and 2015, CFSI consistently delivered a wide range of courses to a large volume of clients. Furthermore, in addition to delivering training that was aligned with departmental and GoC priorities while being responsive to departmental training needs, CFSI made a significant contribution through intercultural effectiveness training, thus gaining recognition for the quality of this training by the former DFATD and Other Governmental Departments (OGD) clients.

The evaluation also found that despite acknowledged capacity limitations, CFSI has effectively supported the delivery of training for most providers throughout the Department. However, findings show that there is a need to update and re-examine some of CFSI’s core offerings to ensure that the training needs of employees continue to be met. Furthermore, evidence from OGD governance models points to the merits of a centralized training delivery (with centralized planning, curriculum design and delivery, governance, administration, national reporting, policy making, and evaluation) and decentralized functions related to subject-matter expertise. Evidence suggests, that by centralizing certain functions, administrative efficiencies in course delivery could be sought (by pooling resources to avoid any duplication of effort) and the consistency of course delivery could be assured.

Based on the evaluation’s findings, observations and analysis, the following four actions are recommended to improve the relevance and performance of CFSI, with a focus on nurturing a learning culture in the Department:

Recommendation #1:

It is recommended that the Department establish a corporate governance body to support the strategic prioritization and delivery of training within the Department. Other government departments have already adopted a centralized model of training delivery.

Recommendation #2:

Pursuant to Recommendation #1, it is recommended that the Department establish a strategy for training delivery. A training strategy would serve to establish a consistent approach to training needs assessment, planning and prioritization and allow for enhanced monitoring of training delivery in collaboration with other bureaus.

Recommendation #3:

It is recommended that the Department explore options for centralizing the core management functions related to CFSI training delivery (funding, curriculum design, learning advisory services, reporting, policy making, and evaluation) while establishing a standardized approach for collaboration with other bureaus on training delivery.

Recommendation #4:

It is recommended that CFSI, in consultation with departmental training delivery partners, should agree on a systematic evaluation strategy and performance measurement strategy, including a data collection mechanism for primary data from training participants, their managers/supervisors, peers, and/or subordinates.

1.0 Introduction

The evaluation of the Canadian Foreign Service Institute (CFSI) is part of the Five-Year Evaluation Plan, and it was conducted to meet the Treasury Board (TB) requirement that all direct program spending be evaluated every five years. This evaluation provides an evidence-based, neutral assessment of the relevance and performance (effectiveness, efficiency and economy) of the CFSI program, with particular attention paid to the training offered by CFSI. The target audiences of this evaluation include the Government of Canada (GoC), training recipients from Global Affairs Canada (GAC), GAC senior management and the Canadian Public.

1.1 Departmental Training Context

As the federal department responsible for foreign policy, trade and development, and as the international platform service provider for the GoC, GAC employees must be equipped with the knowledge, skills, and abilities to deliver federal priorities abroad. This mandate poses challenges on the training front, since training is required that may not be easily met by other learning providers.

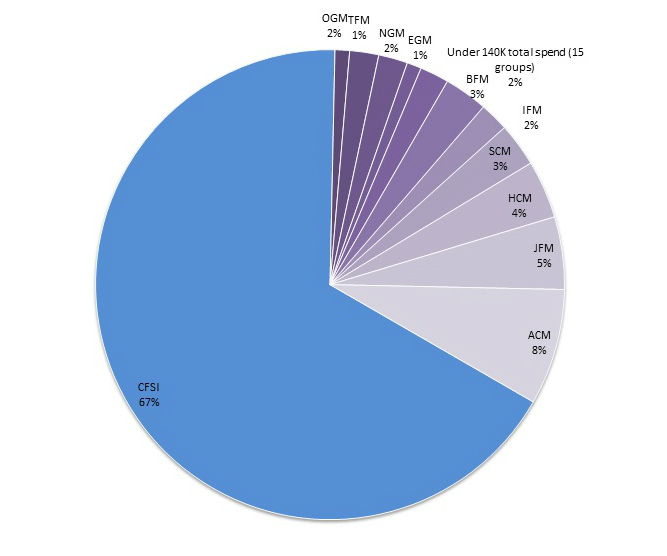

GAC training is delivered by a combination of training providers, including CFSI, bureau-based providers, and others e.g. the Canada School of Public Service (CSPS). In the past four years, from fiscal year 2011/2012 to 2014/2015, the average annual training expenditure across all GAC bureaus was $25.6 million. This total includes an average of $17.1 million from CFSI, which is approximately 67 percent of total departmental training expenditures (please see Table 1 for details).

Departmental training needs are driven by the need to fulfil GAC strategic priorities. Training needs are further shaped by functional communities at GAC and clients within and outside the Department.

1.2 CFSI context

Established in 1992, CFSI is responsible for the professional development and training of employees of GAC and other federal agencies on themes related to international affairs, corporate accountability, management and professional development, through classroom, distance, or eLearning methods. Comprised of four centres (or schools), CFSI offers learning advisory services to departmental and federal clients, delivering over 150 instructor-led and 50 online courses to over 10,000 students, including to overseas missions. Training efforts are monitored and reported upon by CFSI on behalf of departmental training providers, in compliance with the TB Directive on the Administration of Required Training.

CFSI’s primary clients are the nearly 10,000 GAC staff, approximately 40% of whom are locally-engaged staff (LES) (3,671). The remaining 6,187 employees of GAC personnel are non-rotational headquarters staff (approximately 30%) and rotational Canada-based staff (CBS) (approximately 30%), who work both at headquarters and on assignments at missions that last from one to five years. Also among CFSI clients are other government departments (OGDs) and non-governmental organizations who undertake work abroad.

CFSI’s mandate is based on the 2008 DFAIT Learning Policy, which applies to all GAC employees and is implemented in conjunction with the 2006 TB Directive on the Administration of Required Training and the 2006 TB Policy on Learning, Training, and Development.

CFSI is responsible for coordinating the implementation of the above policies and providing advisory services on the development of individual and organizational learning plans at GAC. CFSI supports the deputy ministers’ endorsement of leading-edge management practices, strengthened organizational leadership and the promotion of innovation.

1.3 CFSI Governance Structure and Core Activities

Until the amalgamation of former DFAIT and former CIDA took effect, CFSI resided in the Corporate Planning, Finance, and Human Resources (HR) Branch. CFSI now resides in the HR Branch. Organized into four centres of learning, each centre delivers a suite of training solutions:

- Centre for Intercultural Learning (CFSC)

- Centre of Learning for International Affairs and Management (CFSD)

- Centre for Foreign Languages (CFSL)

- Centre for Corporate Services Learning (CFSS)Footnote 2

The training and learning needs of the Department are served by each of the centres responsible for a given area of training and development. Full- or part-time courses include instructor-led classroom programs, distance learning, and online tutorials delivered to CBS and spouses, LES, and OGD clients. Each centre specializes in providing training in specific areas of study (see Appendix 2). International affairs curricula, for example, are centred on foreign language acquisition, foreign policy and global commerce effectiveness, and intercultural effectiveness.

In addition to the training services offered by the four centres, CFSI offers learning advisory services and an “organizational change and effectiveness” line of service. The latter of the two has been effective for courses related to teambuilding, change management, project and results-based management, communication, management and leadership training, and strategic planning.

1.4 CFSI Partners and Clients

CFSI partners consist of the CSPS and departmental managers, while its client base is GAC employees, managers and OGDs. Departmental managers (from both GAC and OGDs) play a central role informing the development of CFSI training programs. CFSI provides tailored learning advisory services and training initiatives to bureaus. Within GAC, bureaus provide training that is separate from CFSI training. For example, specialized training was provided on niche programs such as security reporting as well as program training for the trade commissioner’s service.

1.5 Program Resources

Table 1 reflects annual CFSI expenditures from 2010-2011 to 2014-2015.

CFSI has 120 employees across its four centres, with the majority of instructor-led courses delivered by contracted instructors. CFSI has offices and classrooms located at the Fontaine Building, Place du Portage, the Lester B. Pearson Building, as well as at a dedicated campus at the Bisson Centre.

| 2010-2011 | 2011-2012 | 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee Salaries | 6,152 | 6,246 | 6,525 | 6,398 | 6,260 | 6,316 |

| Operational Expenses (Training Design and Delivery, Travel) | 11,152 | 12,472 | 13,326 | 9,843 | 7,450 | 10,849 |

| Capital Expenditures | 0 | 6 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Total Annual Expenditures | 17,304 | 18,724 | 19,911 | 16,241 | 13,709 | 17,178 |

2.0 Evaluation Scope & Objectives

2.1 Scope

The evaluation assessed the relevance and performance of CFSI, including the training services delivered, in an attempt to assess delivery efficiencies. This involved examining the mandate, any duplication of effort, and cost-efficiencies or effectiveness related to the choice of instructors (i.e. departmental or contract) and modes of course delivery (e.g. classroom, eLearning). The evaluation covered the period between fiscal year 2010/2011 to 2014/2015, with financial data up to and including March 31, 2014.

The objective of the summative evaluation was to provide a neutral, evidence-based assessment of the relevance and performance of CFSI as a departmental service provider of training, learning and development. The evaluation was also driven by the objective of determining whether GAC is best served by centralized or decentralized training services.

2.2 Objectives

The specific objectives of the evaluation were as follows:

- 1) To evaluate the relevance of CFSI by assessing: whether it continues to address a demonstrable need; the extent to which it is aligned with federal government priorities and the Department’s strategic priorities and training, learning development priorities; and the appropriateness of its current role;

- 2) To evaluate the performance of CFSI in achieving its objectives efficiently and economically; and

- 3) To assess the governance model in place for training delivery at GAC and to draw upon lessons learned from OGDs’ models of training delivery.

2.3 Methodology

The evaluation employed qualitative and quantitative methods and multiple lines of inquiry for systematic data collection, analysis, and the triangulation of data to support the validation of findings and delineating trends, similarities, or points of divergence. For example, course evaluation data was triangulated with CFSI client interviews to determine satisfaction with CFSI services. Performance and financial data was also triangulated with interviews with CFSI management and departmental and OGD clients to assess the efficiency of service delivery.

The evaluation methodology and associated level of effort were calibrated based on consultations and the quality of available information from the following sources:

- CFSI collects some performance information; it shared aggregated data for training delivery and most outputs and immediate outcome indicators;

- CFSI conducted two needs assessments related to foreign language training and management and leadership development;

- An evaluation of CFSI was conducted in 2007; and

- General Ledger (GL) data were available from the Integrated Management System (IMS), which aggregated department-wide training expenditures, including CFSI.

The evaluation employed a mixed-methods approach. Qualitative methods such as interviews and focus groups were primarily applied to respond to the questions of relevance and performance. These methods were complemented by other information sources and analyses, including quantitative analyses.

Two lines of evidence were used in this evaluation: (1) a document review and (2) interviews with direct clients and non-direct clients of CFSI. This also included focus groups with CFSI clients and management. Qualitative data derived from interviews and mission site visits constituted the primary data sources for the evaluation.

(1) Document review: Data was analyzed by evaluation indicators and questions related to CFSI training design, delivery, and evaluation. In addition, reports, CFSI documentation, learning evaluation-related literature, and financial and administrative data were reviewed. Other data sources were documents and program files (e.g. completed needs assessment studies, foundational GoC approval documents, and international as well as national research reports). See Appendix 5 for a list of documents reviewed.

The evaluation team also reviewed approaches to training evaluation across centres. Documents analyzed included strategic and work planning documents, annual reports, information and data on CFSI course offerings, and client evaluations of course offerings. Course satisfaction data was then triangulated with client interviews to assess levels of client satisfaction and employee participation in CFSI training and learning advisory services.

Performance and financial data reviewed included:

Performance data: analysis of available administrative data provided by CFSI staff on financial, human resource, and operations.

Financial data: analysis of departmental and CFSI training expenditures from 2010/2011 to 2014/2015 using established parameters for analysis to understand trends over that period. Bureaus with significant training expenditures outside of CFSI were analyzed, which were identified through an analysis of IMS data. These financial data were then vetted through financial management advisors and CFSI management. Budget and financial data from IMS using GL codes were used to assess the efficiency of CFSI’s operations.Footnote 4

(2) Interviews: Interviews were conducted with 99 key informants including representatives of missions abroad who were CFSI clients, departmental and OGD clients of CFSI, CFSI and departmental management, and OGD senior management who play a role in training delivery. Interviews were also held with Foreign Service institutes of three countries (Japan, Germany and India) to provide a basis for comparison of training models. A summary demonstrating the number and type of interviews conducted is provided in Table 2.

The interview data from the above sources was compiled using an interview summary matrix. Data was categorized according to themes from interview responses which were then triangulated with the document review data.

| Focus Group | Interviewed | Total # Interviewed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFSI client (GAC) | 6 | 13 | 25 |

| CFSI client (GAC Missions) | 11 | 5 | 50 |

| CFSI client (OGD) | 1 | 11 | 11 |

| CFSI Management | 1 | 5 | 8 |

| GAC Management | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Foreign Service Institutes | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| TOTAL | 99 | ||

On-site mission visits were undertaken for another evaluation being conducted in parallel with the evaluation of CFSIFootnote 5 . Thus, the evaluation team used the opportunity to conduct interviews with HOMs, Deputy HOMs, designated mission training/learning co-ordinators and LES at the following missions: Tokyo, Shanghai, Delhi, Tel-Aviv, Sao Paolo, Rio de Janeiro, Brasilia, and Berlin. In-person interview evidence therefore complements document and financial analyses to address the effectiveness or performance of CFSI.

2.4 Limitations

The primary source of data was based on qualitative information provided through interviews with a variety of CFSI clients, managers, and partners (n=99). Statistical analyses are descriptive in nature and costing analyses on operational efficiency are based on existing data verified with CFSI.

Evaluation coverage excludes outcomes related to the impacts of training services on learning acquisition and organization-level outcomes due to the unavailability of data. The scope of this summative evaluation was limited to the delivery of training services, with a focus on the continued relevance of CFSI.

The use of interviews presents the potential for respondent bias, which can limit the ability to generalize evaluation findings to the level of the Department’s view on the continued relevance and performance of CFSI. To mitigate this limitation, multiple sources of analysis are triangulated for evaluation questions about relevance, performance, and to a lesser extent, efficiency.

As noted in the evaluation findings, there were discrepancies between departmental and CFSI financial coding, resulting in inconsistent expenditure data. Consequently, a full cost-effectiveness analysis was not possible. Qualitative data derived from interviews was used for the assessment of cost-effectiveness.

Due to a lack of available data for the cost-effectiveness and efficiency analysis, it was not possible to compare costs across programs, delivery methods (in-class, distance, online), GAC training providers, or external training sources. Analysis of student-day costs can help determine which training delivery modes are more or less expensive, and which programs were delivered to the most students per dollar. Analyses based strictly on student-day costs are limited, however, and they reveal little on the learning obtained for these expenditures. For example, on a student-day basis, a self-directed online learning program may cost half as much as an instructor-led classroom-based learning program on the same subject, but students in the latter case may learn twice as much—in this situation the two delivery modes are equally cost-effective in learning terms. The training field speaks about the concept of “return on training investment,” or ROI. For the purposes of the present study, learning data—gain scores—that could be linked to student-day costs across programs or training modes were not available.

Additionally, given the unique mandate of GAC, reviewing comparable financial data from similar institutions from other countries is difficult. Here, differences in country size, country priorities, organizational structure and other factors would make direct comparisons problematic and would call for numerous qualifications, thus making the comparison unrewarding.

To mitigate these limitations, the cost-effectiveness and efficiency analysis took advantage of additional databases and analyses provided by CFSI and derived from the departmental financial database.

2.5 Evaluation Complexity: Challenges with the Kirkpatrick Model

The leading method for evaluating the effectiveness of training programs is the Kirkpatrick model, which espouses four levels of assessment:

1) learner reaction (satisfaction);

2) learning (knowledge or skills acquired);

3) behaviour (transfer of learning to the workplace); and

4) results (transfer or impacts on the organization).

CFSI has integrated feedback mechanisms with the majority of the training offered. These feedback mechanisms are useful to evaluate the effectiveness of the training from the first and second level outcomes of the Kirkpatrick model. The third and fourth level outcomes, which some might argue are most useful, are least utilized in evaluations of training effectiveness. This is also the case with CFSI as these two outcomes are complex to measure due to difficulties defining the learning context and the cost and level of effort required to obtain this information.

The former-CIDA Framework for Learning - 2011-2014 defines training, learning, and development as follows:

Training: the organized, disciplined way to transfer the knowledge and know-how that is required for successful performance on the job, occupation or profession. It is ongoing, adaptive learning, not an isolated exercise.

Learning: the acquisition of new knowledge and ideas that change the way an individual perceives understands or acts.

Development: the activities that improve self-knowledge and identify. It includes formal and informal activities, and it refers to the methods, programs, tools, techniques, and assessment systems that support human development at the individual level in organizations.

2.6 Questions Addressed

Each evaluation question, as well as sub-questions and indicators for each of the five core issues, are elaborated upon in Appendix 3.

2.7 Challenges to Implementation of Evaluation

The acquisition and validation of data presented challenges due to the multiple training providers at GAC, and the fact that there is no central holding place for CFSI data or consistent process for collecting data across CFSI centres. Each CFSI centre houses its own evaluation and performance data, with some of the course statistical data centralized in one centre.

3.0 Evaluation Findings

3.1 Relevance Issue #1: Continued Need for the Program

Finding #1: CFSI serves an important role in readying departmental and OGD staff for positions at headquarters and missions abroad.

CFSI’s relevance is linked to its ability to address training needs compared with other external and internal training providers (including approximately 26 internal training providers, see Appendix 4 for full list). Departmental financial data shows that training expenditures are dispersed, with approximately two-thirds of the Department’s annual training expenditures spent directly by CFSI. Training provided by the three other largest departmental training providers accounted for approximately 16 percent of the total (International Platform Branch (ACM), International Security and Crisis Response Branch (JFM), and Human Resources Branch (HCM - excluding CFSI).

Chart 1: Average Training Related Expenditures by Branch from 2011/12 to 2014/15

| Branch Name | 2011/12 | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branches / Bureaus: with total spending under $140k annually | 758,349 | 705,223 | 434,870 | 264,520 | 540,741 |

| TFM: Trade Agreements and Negotiations Branch | 334,720 | 305,837 | 327,510 | 190,323 | 289,598 |

| OGM: Asia-Pacific Branch | 365,404 | 441,400 | 400,092 | 365,575 | 393,118 |

| EGM: Europe, Middle East and Maghreb Branch | 440,134 | 208,022 | 374,833 | 500,731 | 380,930 |

| NGM: North American Branch | 405,770 | 861,080 | 367,415 | 272,480 | 476,686 |

| IFM: International Security Branch | 804,323 | 407,665 | 262,240 | 439,138 | 478,341 |

| SCM (SWD): Financial Planning and Management Bureau | 965,379 | 1,007,171 | 560,800 | 507,600 | 760,237 |

| BFM: International Business Development Branch | 802,351 | 817,740 | 921,025 | 623,480 | 791,149 |

| HCMFootnote 6 : Human Resources Branch (does not include CFSI) | 985,605 | 1,607,395 | 975,502 | 779,749 | 1,087,063 |

| JFM: Consular, Legal and Security Branch | 1,125,093 | 1,136,416 | 1,424,802 | 1,622,273 | 1,327,146 |

| ACM: International Platform Branch | 1,813,376 | 1,878,746 | 1,779,233 | 2,265,916 | 1,934,317 |

| SUB-TOTAL (without CFSI) | 8,800,504 | 9,376,696 | 7,828,320 | 7,831,785 | 8,459,326 |

| CFSI | 18,724,329 | 19,910,550 | 16,241,225 | 13,709,188 | 17,146,323 |

| TOTAL | 27,524,833 | 29,287,245 | 24,069,545 | 21,540,972 | 25,605,649 |

| Training Expenditure | Average Expenditure | Percentage of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Training Courses, Seminars and Tuition | $4,417,870 | 51% |

| Purchases related to Training | $166,720 | 2% |

| Teacher and Instructor costs | $719,520 | 8% |

| Language Training Includes English, French and other; not related to pre-posting language training | $1,492,720 | 17% |

| Training Consultants | $1,880,890 | 22% |

| TOTAL: | $8,677,720Footnote 7 |

Not including CFSI expenditures, training costs between 2011/2012 to 2014/2015, the Department spent an average of $8,677,720 per year on training. This includes all non-CFSI training courses, seminars, tuition costs, training related purchases, teacher costs, language training and training consultants.

Evidence of client training needs being met points to CFSI serving a continued need; CFSI also enables training delivery in other parts of the Department. This finding is based on the continued demand for CFSI services, the volume of training offered and the large number of clients served between 2008 and 2014. It is also based on the generally positive feedback received about CFSI training, both within and outside GAC. This is evident in the interview results which indicate the common sentiment that CFSI fulfills central and ongoing training needs of departmental staff.

Although there is a continued need for CFSI, training needs are also being met by bureau providers. CFSI serves as a delivery partner for departmental bureaus.

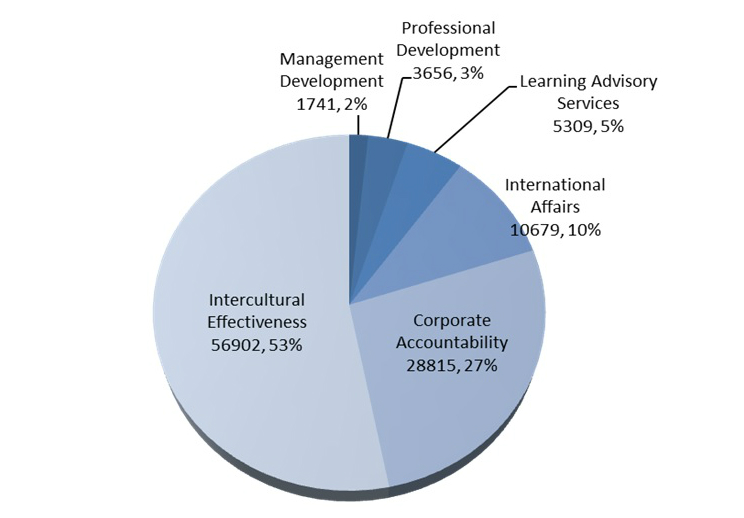

The document review demonstrated that between 2009 and 2014, CFSI delivered a suite of training programs and services to over 96,000 clients. More than half of those received intercultural effectiveness training (56,902), with the majority of those trainees (two-thirds) from OGDs. Nearly 30,000 students were trained in corporate accountability, 70% of which was self-directed online training (courses in communications and interpersonal skills, financial and human resource management, IMS, values and ethics, and information management and technology). Over this period, CFSI delivered over 4,400 training sessions (or 628 sessions annually) using in-class, distance instructor-led, or distance self-directed methods.

There is an ongoing need for CFSI training, learning advisory services, and learning management system provision to continue meeting the training needs of the Department. Alongside the continued need for CFSI training, the need for specialized training delivered by the bureaus remains.

3.2 Relevance Issue #2: Alignment with Government Priorities

Finding #2: CFSI continues to be aligned with departmental and federal priorities.

There is a continued need for training because training, learning and development and continuous improvement are central GoC priorities. CFSI addresses a need in training delivery and supports the delivery of department-wide training. CFSI has a leadership role as mandated by the departmental Learning Policy and is well-placed as the departmental focal point for training and as a facilitator of learning design and delivery, along with training planning and evaluation.

Evidence from the document review and interviews demonstrate that CFSI activities are consistent with GoC priorities and departmental and federal strategic outcomes. CFSI training activities are expected to contribute to the success of the strategic outcomes of Canada’s International Agenda, International Services to Canadians, and Canada’s International Platform. Its activities are also linked to GAC’s Program Alignment Architecture (PAA), contributing to five of the seven program-level PAA outcomes: International Policy Advice and Integration; Diplomacy and Advocacy; International Commerce; Consular Services and Emergency Management; and Governance, Strategic Direction and Common Service Delivery. CFSI also offers courses related to emerging priorities like risk-based management and management development, and provides security-related training.

Alignment with federal and departmental priorities and strategic training outcomes is demonstrated through the mandate of the DFAIT Learning Policy, which aligns with the TB Policy on Learning, Training and Development. In addition, it was demonstrated in March 2014 that CFSI aligns with the Common Human Resources Business Process (CHRBP) outcomes for Managing Employee Performance, Learning, Development, and Recognition.

Training is also an integral feature of HR management. The integrated departmental HR Plan emphasizes that, despite fiscal restraints and realignment of resources within the Department, there is a need for investment in the modernization of the workforce and employee retraining, as well as to fill identified gaps and to ensure that GAC continues to have a high performing, representative and responsive workforce.

Part of CFSI’s mandate is its responsibility for the implementation of the TB Policy on Learning, Training and Development. CFSI’s activities are also aligned with several departmental change management and corporate priorities, including:

- professional development and management development;

- performance management;

- management of organizational transformation and amalgamation; and

- the GAC Common Human Resources Business Process for managing employee performance, learning, development and recognition.

CFSI identifies departmental training needs in “learning roadmaps” for employee occupational groups; these are then aligned with the mandatory training requirements identified in the TB Policy on Learning, Training and Development and its associated directive. Learning roadmaps identify training for eleven functional communities (classified as highly recommended, recommended, based on assignment, and optional training). Learning roadmaps also include suggested courses for improving job performance for each group, making this a relevant tool for multiple areas of the Department. Notably, CFSL identifies foreign language training needs per position, in a comprehensive exercise that is conducted annually. Foreign language needs are then captured in HRMS, which is readily available for manager consultation. Finally, a “Leadership Portal” provides access to leadership development resources within GAC. Learning roadmaps and the Leadership Portal, therefore, allow CFSI to reach the three groups of employees stipulated in the TB directive. These tools help CFSI meet training requirements for three groups of employees as stipulated in the TB Learning Directive (new employees, managers at all levels, and functional specialists) and address one of the Clerk of the Privy Council’s four core functions of public service excellence: management.

According to GAC’s 2013-2014 Integrated HR Plan, GAC’s strategic priorities will be met by ensuring that it continues to “recruit, train, retain, and support talented and knowledgeable personnel”, and to support international policy coherence.

During the evaluation some interviewees suggested that cost-effectiveness can be ensured if the right subject matter is taught; with “right” defined as subject matter aligning with departmental priorities. To a large extent the alignment issue is addressed through CFSI’s needs assessment exercise. However, it was suggested that there is perhaps room for more effort in this respect.

3.3 Relevance Issue #3: Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Finding #3: Not only is CFSI training aligned to Departmental priorities, but the management and implementation of CFSI is also an appropriate role for the federal government and for GAC.

Interviews with CFSI management, senior GAC management, as well as the document review identify training, learning, and employee development as primary responsibilities of the federal government, while developing a competency-based workforce is one of GAC’s central responsibilities.

The acquisition of skills and knowledge and the development of management and leadership are critical for an effective public service and are considered the foundation of a responsive, accountable and innovative government.

CFSI’s activities are reflected in two elements of the Management Accountability Framework (MAF), a performance management tool used by the GoC. These elements are: 1) People; and 2) Learning, Innovation and Change Management.

The GoC’s training and development policies are outlined in two documents:

The 2013 Report of the Clerk of the Privy Council: reinforces the importance of knowledge building and sharing, emphasizes the importance of fostering a learning culture; and

The TB Policy on Learning, Training, and Development empowers deputy heads to guide organizational learning.

Training, learning, and development fall within the mandate of GAC as stated in the DFAIT Learning Policy and departmental planning and performance documents including the Report on Plans and Priorities (RPP), the Departmental Performance Report (DPR), the Integrated Corporate Risk Profile, and the Integrated Corporate Business Plan. The Integrated Corporate Business Plan identifies learning and performance management as an HR priority and internal service.

The document review demonstrated CFSI’s progress toward supporting organizational-level outcome data. Both the Department’s annual MAF submission and the Common Human Resources Business Process (CHRBP) revealed that CFSI is contributing to the departmental management of employee learning and development. This was evidenced by the successful implementation of all seven process areas of the CHRBP. Through CHRBP, GAC ensures that departmental HR services respect a common, government-wide method, enabling government-wide performance measures.

3.4 Performance Issue #4: Achievement of Expected Outcomes

Finding #4: CFSI offers a wide range of training opportunities with most clients expressing satisfaction with these services provided.

CFSI course evaluation data show consistently high levels of satisfaction with course relevance and applicability, including self-rated increases in knowledge and/or skills as a result of training. The exception to this view was for online course offerings, which had satisfaction ratings that were slightly lower than for in-class courses.

Nearly all CFSI clients interviewed within and outside the Department either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “CFSI services have contributed to the achievement of my strategy/operational objectives; I am satisfied with CFSI’s services.”

The departmental clients that either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the above statement cited a lack of capacity and pedagogical expertise for effective course offerings. Some mission training coordinators who were asked about the quality of CFSI services noted that while course offerings and the quality of course material are good, CFSI’s portfolio of courses do not address all training needs. The common view among individuals involved in training delivery was that CFSI should not be offering courses for which subject matter expertise is stronger elsewhere in the Department or with OGDs. In addition, mission interviews with CFSI and CFSL clients revealed challenges with regard to foreign language training; these challenges consisted of the timing of language training in relation to other pre-posting training courses.Footnote 8

For intercultural effectiveness training, a strong majority of client perceptions within and outside GAC were positive. Intercultural effectiveness training constitutes the largest share of CFSI training, with more than half of CFSI training over the last four years devoted to intercultural effectiveness, and two-thirds of those students coming from outside the Department (45,000). The majority of CFSI intercultural effectiveness clients interviewed consider it to be a niche service that cannot be easily obtained elsewhere.

Variability of views on training usefulness ranged widely containing feedback from both polarities, pointing to the need to undertake a review of CFSI curricula to ensure a clear review and renewal process in assessing the training needs of employees and how training can be improved. Understanding learning needs in terms of competencies (mission-specific, required or recommended), individual learning and career paths, or in the context of curriculum design could contribute to the Department’s ability to meet training needs and organizational priorities.

CFSI has a number of memoranda of understanding (MOU) with OGDs for intercultural effectiveness training, and it has established targets for increasing this number. Although CSPS is considered a learning partner, there is no formalized partnership between CFSI and CSPS. CFSI has supported the participation of Foreign Service officers in leadership courses offered by CSPS. According to one mission, this support resulted in positive views about CFSI for facilitating and promoting such partnerships; it also served to increase CFSI’s profile. Work remains to formalize the relationship with CSPS in order to clarify the respective roles of CFSI and CSPS in international affairs training. Partnerships with bureau clients are also not formalized.

CFSI’s portfolio of courses does not address all training needs, particularly in cases when subject matter expertise resides elsewhere in the Department. Capitalizing on the subject matter expertise of OGDs requires a measure of standardization (such as a government-wide portal to facilitate access to training). CFSI does not currently perform this function.

In addition to course offerings, CFSI delivers organizational effectiveness support through its Organizational Learning Fund (OLF), which allocates approximately $3,500 per request for clients at headquarters and missions. Nearly two-thirds of training applications for OLF services are from missions.

In terms of determining departmental training needs, CFSI conducts periodic needs assessments and reaches out to staff where feasible. As a result, there is some variability across the Department in how learning needs are assessed and addressed. For example, mission interviews revealed that CFSI does not normally reach out to missions. Instead, missions generally develop and implement learning plans independent of CFSI.

Taking the above into account, the evaluation findings underscore the continued need for both CFSI and bureau training. As one interviewee stated, “we don’t think about who offers the training, we think about business lines.” Most missions interviewed are satisfied with the level of support received from CFSI, noting that in most cases CFSI courses and advice were well-suited for pre-posting preparation or for the specifics of positions abroad.

Finding #5: CFSI awareness tools such as its internal website are effective at reaching a large number of people. This has assisted with the high volume of clientele using CFSI’s services each year.

CFSI’s relevance and performance are also demonstrated by the extensive scope of CFSI course offerings as well as CFSI’s role in facilitating the fulfillment of the TB Policy on Learning, Training and Development. This is accomplished by increasing employee awareness of and access to training. CFSI reaches a high volume of clientele every year. These clients are generally satisfied with training service, but as mentioned above, a few have expressed that the trainings are too generic.

Between 2011 and 2014, the “CFSI Virtual” internal website received an average of 1.6 million hits annually, and in 2014, the website received more than 10,000 unique visitors.

CFSI training was provided to CBS (3,654), LES (10,509), and close to 57,000 OGD clients in intercultural effectiveness, over 6,000 of whom were GAC clients.

As seen in Chart 2 below, the majority of training was delivered in corporate accountability and intercultural effectiveness; with the former primarily based in online self-directed learning. In addition to delivering training, CFSI houses a central learning management system for course registration (including for courses delivered by other bureaus).

The chart below illustrates the distribution of training by subject between 2009 and 2014. The primary employee groups served by these curricula are FS, EC, CO, EX, and AS.

Chart 2: Students Trained by CFSI: 2009-2014*

CFSI’s learning management system and its learning advisory services are considered to be “essential” and “critical” by bureau clients for enabling the delivery of bureau-specific training. Respondents referred to CFSI’s efficient service delivery and ability to build a knowledge base as something bureaus are unable to do without CFSI support.

CFSI contributes to learning design and provides operational support by providing platforms (classroom, online interface) and helping to hire qualified instructors. One interviewee stated that without CFSI, there would have been no funding or expertise to design effective training or to undertake needs assessments in his/her bureau. Some departmental clients identified a lack of CFSI support, commenting that CFSI could improve support for online learning.

Finding #6: A learning culture at GAC is in its infancy.

Interview evidence suggests that there is a need to support a learning culture at GAC. Suggestions included investing in learning “coaches” who could support employee career planning and development, as well as increasing managers’ participation in the employee learning process (e.g. undertaking pre- and post- assessments of learning outcomes and on-the-job effectiveness). Another suggestion was to improve knowledge sharing after learning events among peers, which would encourage organizational learning and, at a more practical level, facilitate transitions in a department with a large number of rotational positions.

According to the learning evaluation literature, the single most influential factor for the application of training is social support. Targeted interventions with both trainees and the people who interact with trainees (e.g. coworkers, supervisors) are most likely to result in a supportive training and learning environment.

A notable finding from the literature review is that while the Kirkpatrick evaluative model is most common, its application at the organizational level is rare given the difficulties of measuring organizational impacts of individual training. This is evident with CFSI, which has a reasonably high response rate (about 73%) of evaluations for Level 1 and Level 2 outcomes (reaction and behaviour related to training), but has little to no data on Level 3 and 4 outcomes.

GAC has informal and formal mechanisms in place for the planning and delivery of training and learning. These include the following networks/working groups, which have a learning component or are entirely learning-focused:

- DFATD Trainers Network: brings together trainers and learning facilitators from all bureaus to share information and best practices, to encourage networking between group members and to establish partnerships for new learning projects. The network is expected to represent a significant resource for all trainers;

- CFSI eLearning Network: shares information and best practices for eLearning, encourages networking between CFSI and GAC employees who are interested in eLearning and provides a forum for CFSI and GAC employees to share information on eLearning projects under development;

- Mission Learning Coordinators Network: is a forum for all learning, training and development issues concerning mission staff. It allows coordinators to share ideas and best practices and to collaborate across the globe. CFSI is the focal point at headquarters, liaising and collaborating with program managers who are responsible for training at the missions.

- Consular, Security and Emergency Management Learning Advisory Committee (LAC):responds to the need for more and specialized consular training. This need was identified by staff at mission conferences (2008), in Mission Inspection reports (2004-2007) and in the TB Submission on Consular Services and Emergency Management (2008).

- Distance Learning Network: meets bi-monthly and includes fifteen OGDs who share best practices and new trends in the area of eLearning.

In addition to the above networks/working groups there are the Trade Learning Committee, the Heads of Learning Forum, the Security Working Group, the MCTP/MCO Renewal Committee, and the LES Governance Committee.

Some missions have set up training committees, tasked with identifying the training needs of personnel and developing a training budget. There are, however, no standard terms of reference for these committees or formalized roles and responsibilities (e.g. training coordinator job description, even though each mission is expected to have one). As a consequence, the effectiveness of these training committees varies, with the attendant consequence of unfulfilled training needs and expectations.

CFSI participates in consultative networks across bureaus, which focus on identifying training and learning priorities in the political, trade, and management streams. The extent to which the existence of these networks serves a strategic coordination role is unclear. It is also unclear whether these networks nurture a “learning culture” within GAC, and if so, how. There exists the potential to leverage these networks or to consider strategically how they may serve the promotion of a GAC learning culture more broadly.

Finding #7: CFSI has made progress towards the achievement of outcomes related to training delivery, yet there is a lack of centralized performance monitoring and evaluation of learning and organizational training, learning, and development outcomes.

| Expected Outcomes | Examples of Indicators Used to Measure Change in Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Meeting GoC’s training commitments/ requirements |

|

| Satisfied employees confident representing Canada to the world |

|

| CFSI sought/seen as the Centre of Expertise in Learning in international affairs for all of the GoC |

|

The evaluation compared outputs and outcomes against expected outcomes, as noted in Table 5. The table provides examples of indicators used to measure progress toward outcomes. Because CFSI only collects data related to the reaction of students and learning (Level 1 and Level 2 outcomes data as per the Kirkpatrick model, see pg.13 2.4) only three impact-related outcomes were reported in this evaluation.

Based on interviews, CFSI documents, and course-level data, evidence indicates that progress has been made toward the achievement of the following outputs and immediate outcomes:

Outputs:

- Departmental training policy

- Training needs assessments (completed two in 2008-2013 period)

- Course catalogue and materials (available electronically)

- Classroom, distance learning, and eLearning offerings

- Course/program evaluations

- MOUs with partners

Outcomes:

- Meeting GoC commitments/requirements for training

- Employees equipped with required knowledge or skills

- CFSI sought out by OGDs for expertise in international affairs training

Document and interview evidence identified gaps affecting the achievement of CFSI outcomes:

- A lack of centralized performance monitoring and evaluation of learning and organizational training, learning, and development outcomes; and

- An absence of a strategic approach to training planning at the departmental level.

Finding #8: While CFSI is fulfilling its role as a central training provider and making progress in the coordination of training delivery, it is difficult to measure the overall impact on the organization resulting from CFSI training.

CFSI demonstrates that it meets departmental training needs with its generally high levels of client satisfaction, as validated in interviews and course evaluation data. This evidence demonstrates CFSI responsiveness to training priorities and emerging training needs for departmental and OGD clients. These results do not, however, take into account higher-level learning outcomes related to the application of training (behaviour change) and the organizational impact of training (return on investment). Although perceptions of the relevance and design of CFSI training are consistently positive, no higher-level training outcomes at the individual and organizational levels are available to ascertain the impacts of training.

Due to the difficulty of measuring behaviour (the transfer of learning to the workplace) and results (transfer or impacts on the organization) under the Kirkpatrick model (see pg. 13), there is a lack of available data on some potential areas for improvement. This is primarily due to the fact that course evaluations do not assess the impacts of training on trainee behaviour or on the organization as a whole. Thus, there are no apparent links between training evaluation and the performance management process.

Efforts are made to improve training (e.g. running pilots to enable a more nimble and responsive curriculum). At CFSD for example, 80% of courses have been changed over the last two years. However, there is no formalized approach for training (re)design, curriculum review, and needs assessment within CFSI or the Department.

The course development process is also not formalized, and CFSI is not always consulted for course development, particularly in bureaus that deliver their own training and hire learning specialists (e.g. the trade and political streams). Some bureaus that deliver training do not have learning specialists in place, and as a result training products do not always incorporate adult learning methods. CFSI management note the lack of consultation for course design, attributing it to the gap of subject matter expertise at CFSI. They referred to the potential value of CFSI as a “one-stop shop”, where all learning advisors and expertise could be co-located.

Finding #9: CFSI has taken steps to be an effective training program, but the absence of a departmental strategy for training or a broader governance framework limits CFSI’s performance.

While CFSI’s governance is clearly articulated within the Institute, departmental management accountability and oversight roles are less clear. There does not appear to be a strategic integrated portfolio management for the planning and implementation of training.

Across all interviews and the document review, the need was identified for a governance framework that supports the strategic prioritization and delivery of training within the Department. With more than 25 training providers, it is challenging to strategically manage training-related expenditures. Analysis revealed several gaps in GAC’s efforts to strategically plan and prioritize training and to link training efforts to improved performance and results.

Two notable factors which influence performance are: (1) the fact that training is not part of the strategic planning process at the departmental level, (2) the fact that there is not a department-wide training and learning strategy that can be informed by CFSI’s expertise. CFSI also lacks a systematic, comprehensive needs assessment process for training that incorporates all bureaus and overseas posts. These factors contribute to the potential for overlap or duplication of effort.

There were diverging opinions regarding the role that CFSI should play. Certain interviewees across bureaus felt that CFSI should continue to provide administrative support to facilitate the delivery of non-CFSI training within the Department, with subject matter expertise remaining within bureaus. Others felt that training-related services should be centralized within CFSI, with learning specialists co-located within CFSI.

Some interviewees advocated for the consolidation of various funding sources for training into a single pool with common terms and conditions. Sources of training funds currently come from a variety of sources, each with their own terms and conditions. For example, some mandatory training for mission staff is only offered in Ottawa, but eligible expenses related to course participation do not include travel costs, which must be drawn from other funding sources. Some funding sources are only available during limited periods of the year (often the second half of the fiscal year).

With the amalgamation of former-CIDA and former-DFAIT, there is opportunity to establish a combined learning policy and governance framework. Synergies and strengths from the former CIDA’s Framework for Learning – 2011-2014 and the DFAIT Learning Policy could form the basis of a new, department-wide governance strategy for training, learning, and development.

According to the document review, CFSI recommended that it become mandatory for managers to complete and share learning plans with CFSI and the Learning Network. Related recommendations were that managers include competency gaps in their human resource and learning plans, and that a governance structure and associated management system linking performance to learning be established (allowing cascading learning priorities and needs to be linked to business priorities).

In this regard, a strategic planning framework that assesses how CFSI plans, designs, implements, and evaluates training would be useful. It could oversee all four elements of a training program including planning, design, implementation and evaluation. This type of framework is similar to what OGDs do in their type of delivery models (described in greater detail in section 5.0).

A comparison of course offerings from CFSI’s four centres, other departmental providers and CSPS revealed that there is little or no overlap within the department and some overlap between CFSI and CSPS courses. For example, CSPS, as a part of its international services, offers “How China Works” and “How the EU Works” courses to senior executives and public service clients. CFSI was approached to provide input into the design of these courses.Footnote 9

The extent of overlap in course content between CFSI and CSPS is unclear, and there is no evidence of plans to delineate the roles of CFSI and CSPS for the delivery of international affairs training. CFSI would benefit from clarification to target clientele, course content, and training objectives vis-à-vis CSPS.

3.5 Performance Issue #5: Demonstration of Efficiency & Economy

The evaluation team engaged the services of a consultant to assess the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of CFSI. Evaluation findings and recommendations are based on the synthesis of qualitative observations as well as costing analyses of operational efficiency.

Training expenditures were assessed across bureaus to determine the extent to which the current training delivery model meets GAC and GoC needs. For example, significant spending on external training providers for a particular subject may indicate a gap that is not currently filled by CFSI.

In addition to examining CFSI, OGD training delivery models were reviewed to provide a basis for comparison for departments with similar training characteristics to GAC. This evidence was gathered to determine whether a centralized or decentralized delivery model is optimal. Several observations were made regarding these OGD training delivery models; however, an in-depth analysis was not possible within the timeframe of the evaluation due to the differences in mandates, activities, funding, budgets, and information availability.

The assessment of efficiency and economy, based on key informant interviews and a document review, considered the following measures:

- Any identified duplication of effort within CFSI and across the Department;

- Training demand, frequency and volume of delivery, and delivery modes, in conjunction with perceptions of training quality, usefulness and applicability;

- Cost-benefit analysis for modes of course delivery (distance, in-class, or online) and types of instruction (in-house or contract instructors); and

- Average training expenditures per student-day.

Findings from the cost-effectiveness and efficiency analysis contribute to the assessment of whether the current system of training delivery and resource allocation is optimal, or whether there are alternative, more effective or economical ways to achieve the same results or better.

Finding #10: There is evidence of efficiency. Actions have been taken by CFSI to balance the efficiency, reach, and quality of course delivery. CFSI continues efforts to identify cost-effective approaches to training delivery.

As demonstrated in Table 8 (page 32), it was found that the number of students per session, averaged across four major CFSI program areas, increased between 2008-2009 and 2011-2012 from 7.28 students per session to 18.36 students per session. Qualitative evidence suggests that CFSI employees, most of whom are learning specialists, have worked to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of CFSI’s courses and programs. CFSI representatives interviewed described measures taken to increase efficiency in such areas as procurement/contracting, use of internal or lower-cost subject matter experts, cancellation of courses with too few registrants, continuous improvement of courses based on systematic observations and evaluations, use of inexpensive training venues, and minimization of travel for training.

With regard to the cost-effectiveness of training delivery at missions, courses offered online or through webinars are rapidly becoming the preferred delivery option. There is a trend toward instituting electronic course delivery as more cost-effective than alternatives (e.g. sending trainers to mission, bringing mission staff to Canada for training).

Interviews with CFSI management revealed that efforts have been made to review training needs at missions (beginning in fall 2011), particularly for LES. For example, LES training was previously offered only at headquarters four times annually in groups of twenty for two weeks of training. Given the high costs involved ($400,000 to reach 80 LES), training has now moved from being two weeks in duration to one week, delivered regionally rather than at headquarters. In addition, the teaching approach is blended, with online courses provided prior to the in-class session.

CFSS also introduced LES-to-LES coaching, which is described as an effective training method for new LES. Delivery has also been changed, with common training delivery points established to reduce travel costs.

Finding #11: The largest expenditure for the CFSI was foreign language training provided by CFSL—representing 36 percent of expenditures.

Table 6 summarizes expenditures, student-days, and costs per student-day across the four centres and for CFSI’s central functions.

| CFSI Central Functions | CFSL | CFSC | CFSD | CFSS | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $000s | ||||||

| Salaries | 224 | 1,440 | 844 | 1,191 | 2,658 | 6,357 |

| Operational CostsFootnote 10 | 105 | 4,809Footnote 11 | 501 | 1,068 | 1,211 | 10,772 |

| Travel | 13 | 57 | 8 | 171 | 506 | 755 |

| Capital Costs | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 17 |

| TOTAL | 329 | 6,252 | 1,353 | 2,259 | 3,882 | 17,146 |

| Average Student-days | ||||||

| Instructor-led Classroom | 12,625Footnote 12 | 10,536 | 3,425 | 2,628 | 29,214 | |

| Instructor-led Online | 0 | 0 | 13 | 470 | 483 | |

| Self-directed Online | 0Footnote 13 | 244 | 391 | 1,677 | 2,312 | |

| TOTAL | 12,625 | 10,780 | 3,829 | 4,775 | 32,009 | |

| Average Cost per Student-dayFootnote 14 | ||||||

| $342 | $126 | $611 | $830 | $723 | ||

While efforts are being made to improve training efficiencies abroad, missions continue to develop their own training. One reason, according to the interviews, is that headquarters are not fully meeting the training demand. CFSI management expressed the importance of being involved from the planning stages of training to facilitate training needs identification. In a similar vein, allowing CFSI to sit on the corporate management committee was suggested as a means of ensuring that training needs be aligned with corporate priorities.

As shown in Table 6, the average annual total CFSI expenditure between 2011/12 to 2014/15 was $17,146,320. This figure does not include infrastructure costs or costs associated with the salaries of the employees in training and of GAC employees serving as subject matter experts in courses. The travel expenditures shown in the table do not cover travel associated with travel covered by the employee’s mission or home bureau.

The largest expenditure, representing 36 percent of the total, was for foreign language training provided by CFSL, followed by corporate and administrative training provided by CFSS (23 percent), international affairs and management training provided by CFSD (13 percent), and intercultural training provided by CFSC (8 percent). CFSI central function expenditures accounted for the remaining two percent of CFSI’s average expenditures.

For CFSL, all training is designed and delivered by contract instructors; contract instructor fees are CFSL’s largest expense. CFSL also transfers funding for foreign language training to missions and other GAC bureaus; these transfers are CFSL’s second largest expenditure.Footnote 15 Student-day figures provided for CFSL do not include training days covered by transfers; cost per student-day calculations were therefore based on total annual expenditures without including transfers to missions/other bureaus.

By way of comparison, the Canada School of Public Service (CSPS) currently advertises classroom-based instructor-led courses ranging from $311 to $1,582 per student-day. The Niagara Institute, a private, not-for-profit organization that is part of the Conference Board of Canada, currently advertises classroom-based instructor-led courses ranging from $958 to $3,345 per student-day. Student-day fees at CSPS and the Niagara Institute include infrastructure costs and the costs of all subject matter experts, but do not include travel and travel related costs. It is important to note that many of the CFSI training courses include international travel (ex: Locally-Engaged Staff training).Costs per student-day for training provided by other providers within GAC could not be calculated due to the lack of student-day information. However, as shown in Table 7 the three largest training providers (besides CFSI) spent a combined annual average of $8,387,000 on training.

| BTR – Trade Commission Service | CLD – Consular Policy & Advocacy | CEP – Policy Emergency Planning & CET – Policy Training | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $000s | ||||

| Salaries | 1,647 | 2,898 | 1,560 | 6,105 |

| Contractor Costs | 159 | 379 | 99 | 637 |

| Travel | 264 | 494 | 207 | 965 |

| Ancillary Costs | 60 | 521 | 99 | 680 |

| TOTAL | 2,130 | 4,292 | 1,965 | 8,387 |

CFSL’s funding was increased significantly in 2011-2012 as a result of a TB decision to increase GoC support for foreign language training. At the same time, CFSL’s accounting methods were improved. Although this change facilitates analysis of foreign language training expenditures, it also makes it difficult to compare expenditures from before and after 2011.

Finding #12: With instructor-led classroom training being the most prevalent form of training with CFSI, it is unlikely that the self-directed online learning is being used to its full potential.

A direct comparison of the various course delivery modes is not possible with available data, since expenditure data is not broken down by delivery mode. It may be observed, however, that the four centres use different blends of the three main learning modes (in-class, distance, online). Observations can therefore be made with respect to student-day costs associated with each centre and the potential influence of delivery modes on these costs.

Instructor-led classroom training is the most prevalent delivery mode by far, accounting for 91% percent of the 32,009 student-days provided by CFSI in an average year (see Table 6). With self-directed online and instructor-led online courses only accounting for 9 percent of the student days, there may be room for expansion of these types of courses. However, given that most centers have a mixture of both in-class and online courses, it is difficult to determine what is the most economical method for course delivery.

Despite the fact that students generally indicate their preference for in-class and experiential learning methods over online learning, 60 out of 150 courses are currently offered online. There have been no studies undertaken regarding their usefulness for the material being delivered vis-à-vis other methods of delivery and/or as a measure of cost-effectiveness. Thus, this is an area that needs more study.

Finding #13: During the years covered by the evaluation, CFSC spent nearly ten times more on intercultural training for individuals from outside the Department (on a cost-recovery basis) than it did for GAC employees.

Most CFSC training is designed and tested internally by CFSC employees, then delivered by contract instructors. During the years covered by the evaluation, CFSC spent nearly ten times more on intercultural training for individuals from outside Department (on a cost-recovery basis) than it did for GAC employeesFootnote 16 . In three of the four years for which expenditure data were collected, fees charged to individuals from outside of the Department supplemented departmental funds to help pay for GAC employee training.

Finding #14: There is little consistency between the staffing models between the four centres of CFSI. Thus, it is impossible to determine the cost-efficiency of the student costs between the different centres.

Each of the four centres has its own subject matter and training objectives as well as its own learning specialists. Staffing models also vary between centres: in some cases training is developed and delivered by centre staff, in other cases these services are contracted out.

Ordered from highest student-day costs to lowest, the following list summarizes the different staffing models across centres:

- CFSS: employees design and deliver most training; 35 percent of student-days were spent with self-directed online learning, 10 percent with instructor-led online learning, and the remainder with instructor-led classroom learning. CFSS employees design and deliver most of the centre’s training.

- CFSD: contractors design and deliver all training; 10 percent of student-days were spent with self-directed online learning, and the remainder with instructor-led classroom learning. CFSD employees attend instructor-led classroom training as observers both to provide administrative support and for quality control purposes.

- CFSL: contractors design and deliver all training; all of which was delivered with instructor-led classroom learning.

- CFSC: employees design training, contractors deliver training; seven percent of student-days were spent with self-directed online learning, and the remainder with instructor-led classroom learning.

With competing explanations, it is impossible to conclude whether or not student-day costs are higher or lower at different centres due to the centres’ particular staffing/contractor mix.

Finding #15: Employees can monitor less-than-effective activities and correct and improve problems with regular in-class observations and course evaluations. Nonetheless, to improve efficiency, there is a need for empirical monitoring and the existence of one database to collaborate information between the four centres.

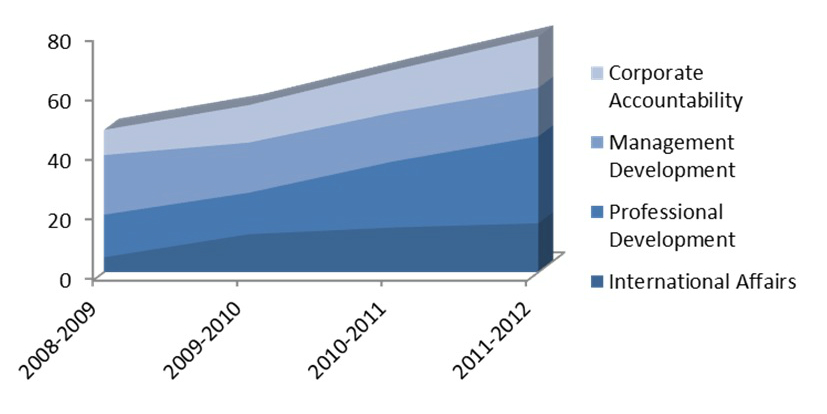

| 2008-2009 | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011 | 2011-2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Accountability | 8.42 | 12.52 | 14.21 | 17.13 |

| Management Development | 19.90 | 16.75 | 16.33 | 16.21 |

| Professional Development | 14.22 | 13.84 | 22.09 | 29.04 |

| International Affairs | 4.97 | 12.67 | 14.91 | 16.32 |

| AVERAGE TOTAL | 7.28 | 12.83 | 15.87 | 18.36 |

Chart 3: Students per Session by Major Area

As can be seen in Table 8 and visually in Chart 3, the total number of students per session increased substantially between 2008-2009 and 2011-2012 from an average of 7.28 students per session to an average of 18.36 students per session. Only the management development program showed a slight decrease in students per session.

CFSI’s efforts to monitor training efficiencies are in large part anecdotal. Most CFSI employees are capable of identifying inefficiencies or otherwise less-than-effective activities, and correcting or improving problems. With systematic measures such as regular in-class observation and course evaluations, it could be argued that CFSI staff has the tools to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of its courses.

There is, however, a lack of empirical monitoring. CFSI expenditures are not recorded by delivery mode or subject matter in a way that would allow CFSI officials to address questions and compare approaches empirically. The fact that different databases had to be accessed for the present study to obtain accurate data for the four centres suggests that there is room for improvement in this regard.

CFSI collects little in the way of learning gain data. The absence of such data inhibits CFSI’s assessment of training ROI, and thus the cost-effectiveness of CFSI training. The exception is CFSL, which tests foreign language proficiency before and after training allowing gains to be precisely calculated. Although it currently does not do so, CFSL could correlate gains with training expenditures and compare training efficiency across such indices as delivery modes, programs and subject matter (e.g. languages of varying difficulty).

CFSI has a mandate to coordinate department-wide training, to provide common registration and other administrative services to all GAC training providers, and to provide expert advice in areas like needs assessment and training design. Take-up of these services is inconsistent, which may lead to either duplication or potentially lower quality services. At a time when many GoC departments have a single “one-stop-shop” source for all formal training and related learning services (typically housed in the HR Branch), the fact that there are 20 to 25 training providers within GAC suggests that there may be inefficiencies. Cost-effectiveness is not just a matter of CFSI delivering its training in the most efficient way possible; it is also about CFSI fostering efficiency in training across the Department, regardless of who is delivering the training.

As reported by interviewees, there is the lack of integration between various systems employed to manage GAC training. CFSI uses a learning management system (LMS), which tracks participant registrations and completions. Nonetheless, the LMS is not integrated with the Department’s human resource management system (HRMS). This causes relevant training-related data to reside in one system or the other but often not both, creating gaps in the databases and reducing potential for analysis. Furthermore, it can create a situation of potential duplication which may reduce the overall efficiency of training at GAC. Without complete information, personnel-related decisions may not be well-informed. For example, if a broad skill gap is identified among a certain employee group, it may be possible to fill the gap more easily and inexpensively through recruitment rather than through training.

CFSI’s LMS has the potential to serve the entire Department. It could help reduce administrative duplications, enhance consistency, gain economies of scale, and support the kind of monitoring described above. As the LMS is not used uniformly across departmental training providers, these benefits have not been realized. Thus, while interviewees reported that there is “no duplication of courses in the Department” there may well be duplication of course administration activities. Interviewees reported having observed instances of a lack of coordination across training functions and activities (e.g. missed opportunities to offer a coordinated series of courses from CFSI and other providers to LES when they are brought to Canada).

5.0 Evaluation Findings on Performance of Training Models With OGDs