Archived information

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

International Trade and Its Benefits to Canada (2012)

Canada depends heavily on trade to sustain incomes and living standards of Canadians and the prosperity of the nation. Consider that, in 2011, Canada’s exports and imports of goods and services were approximately $1.1 trillion in total— which is, on average, about $31,600 for every person in Canada, or $3 billion each and every day—and that the overall size of Canada’s economy, as measured by its gross domestic product (GDP), was $1.7 trillion last year. Thus, the share of trade in the economy was about 63.3 percent in 2011. Indeed, the share of trade in the economy has risen over the decades, in particular during the 1990s when it climbed nearly 34 percentage points following the elimination of most of the trade-dampening tariff barriers between Canada and two of its most important trading partners—the United States and Mexico.

But statistics only partially highlight the importance of international trade to Canada and Canadians. Economic models and theories can also be used to ask the question of what is the benefit of international trade to Canada. The answer to the question is, however, multi-dimensional and not entirely computable. From one vantage, the trade data suggest, as a first order of approximation, that one in five jobs in Canada depend on exports, either directly or indirectly.Footnote 41 Yet this is simply an accounting of how much spending in the economy is accounted for by exports. Taken from another perspective, this vastly understates how dependent Canada is, and Canadians are, on trade. The structure and the organization of the entire economy are crucially dependent on trade and integration with regional and global trading networks.

The purpose of this special feature is to delve deeper into the benefits that trade brings to an economy and/or its citizenry. The focus is on Canada and, where possible, we bring forward evidence that pertains to, or can be applied to, Canada. The theoretical aspects of the analysis have been confined to a few broad sections. We have tried to keep these portions as short and non-technical as possible, perhaps too general for the more technical reader. However, the key message about the benefits of trade is intended for the average Canadian—who may never have realized how much trade improves the quality of the Canadian way of life.

The Importance of Trade

Many of the benefits of exports to Canadians are straightforward. Exports allow Canadians to sell their goods and services in exchange for foreign goods and services. They also help to support jobs in Canada, directly to those producing the goods and services, and indirectly to those providing supporting activities to the producers of Canadian exports. Other benefits are less tangible. For example, exports mean added production beyond that produced for the domestic market, which allows for economies of scale in production and lower average costs for producers, in turn lowering prices for consumers. Competing in export markets also means seeking out efficiencies and being innovative in all aspects of business. Rather than trying to produce many products, firms tend to focus on and specialize in products or services where they have an advantage. This drives up their productivity, allows firms to pay higher wages, and helps to increase the prosperity of the nation. Firms that rise to the challenges of the export marketplace increase their production volumes and become larger. They develop wider and deeper client bases and are better able to withstand downturns and softer market conditions in a region, thus becoming more secure and stable employers. For governments, larger and more-efficient firms are more profitable and thus pay more in taxes, providing additional revenues to the public coffer. These benefits, while indisputably real, are difficult to capture empirically.

The level of income in a nation is a reflection of the efficiency with which the resources of that nation are combined to produce goods and services and the relative value of the price of the nation’s goods and services that are exported compared to those imported (i.e. the terms of trade). As a small economy, Canada produces only a fraction of the goods and services it consumes and imports the rest. In a world devoid of international trade, it would be unrealistic to think that a country like Canada could make the necessary investments to produce the range of products and services it presently enjoys. In other words, Canadians’ access to a broad variety of foreign-made machinery, computers, and communications technologies, and to travel and entertainment services, for example, reflects Canada’s ability to sell Canadian-made goods and services in international markets.

Indeed, it would be very difficult to imagine a world without international trade for the average Canadian. The typical Canadian starts the day by awakening to the sounds of a clock radio. Inside that radio, the alarm mechanism is controlled by a microchip. That microchip, and indeed the entire clock radio, was most likely imported. Even the bed linen, whether cotton or polyester, is made of fibres that are likely imported. When the typical Canadian sits down to scan the day’s headlines while eating breakfast, the glass of orange juice or cup of coffee or tea on table are imported goods: the oranges, tea, and coffee originate from other parts of the world. And the headline news, about fiscal austerity in Europe or a natural disaster somewhere in the world, is a service imported into Canada from an international newswire.

Many of the cars the typical Canadian encounters on the daily commute have direct or indirect foreign connections. Roughly one third of new cars in Canada are built overseas, another third are transplants built in North America by foreign-owned manufacturers such as Toyota or Honda, and the remaining third are North American “big 3” carsFootnote 42 containing subcomponents sourced from countries around the world.

The typical Canadian’s cell phone and computer were likely manufactured in another country as well, with the subcomponents, such as microprocessors and RAM, produced and/or assembled in still other countries. The operating software and many of the software programs on these devices are also likely of non-Canadian origin. Likewise, many commonly used food products, ranging from spices and out-of-season fruits and vegetables to nuts and chocolate, and even many appliances in Canadian kitchens, are also imported. International trade enriches the lives of everyday Canadians in so many ways and through so many direct and indirect channels that it would be virtually impossible to disentangle its effects or to precisely measure the innumerable benefits and conveniences it brings.

But imports also have other effects on the economy beyond providing variety and choice for consumers. Imports provide inputs to producers and competition for Canadian producers. They provide jobs directly to people in the transportation, wholesale, and retail sectors and indirectly to many others whose activities support those involved in importing; the bankers, for example, who arrange for the exchange of currencies and transfer of payments.

Specialization, Comparative Advantage, and Gains from Trade

Economic theory has one central explanation for the process of wealth creation resulting from trade: let people do what they do best or, in one word, specialization. Throughout economic history, mankind has gradually increased its economic well-being through specialization. The division of labour, specialization, and the international exchange of goods and services have been key to improving economic conditions. As specialization increased, so has productivity and total output, leading to a larger economic pie to be divided among the population.

There are many instinctive reasons that make specialization more efficient. First, the specialist acquires more expertise and performs better over time. Second, specializing avoids the costs of switching between different activities. Third, specialization avoids the need to provide everyone with a different set of tools for all activities. Finally, economic agents can choose occupations that they enjoy more and thus be better at it.

Trade among nations further accentuates the importance of specialization by allowing the gains from specialization to be extended to a wider area.

In the context of international trade, economists have developed the concept of comparative advantage, in which one party is better than the other at producing all goods and services, but by a different margin. The concept of comparative advantage was first articulated by David Ricardo in 1817, using an example involving England and Portugal and two goods (cloth and wine). Ricardo showed that even when one of the two countries has an absolute advantage in producing both goods (i.e. it can produce more output with one unit of labour in both sectors) there is scope for mutually beneficial trade if both countries specialize according to their pattern of comparative advantage.Footnote 43 More precisely, it is said that a country has a comparative advantage in the production of good X if it is relatively more productive in the production of that good.

It is differences between the relative prices between countries (as reflected in costs of labour to produce the goods) that underpin the incentive to engage in trade.Footnote 44 The divergence between self-sufficiency and free trade prices only partially explains the gains from trade. A more complete explanation of those gains should also take into account the underlying factors that give rise to different prices, thereby creating the conditions for mutually beneficial trade. These factors are the ones that lie behind the sources of comparative advantage. They include such things as differences in technology and differences in natural endowments. In addition, there are other gains from trade that are not linked to differences between countries. In particular, countries trade to achieve economies of scale in production or to have access to a broader variety of goods. Moreover, if the opening-up of trade reduces or eliminates monopoly power or enhances productivity, there will be gains from trade beyond the usual ones. Finally, trade may have positive growth effects.

Differences in Technology

As already mentioned, differences between countries are one of the main reasons why they engage in trade. The Ricardian model and its extensions point to technological differences as the source of comparative advantage. This was illustrated in Ricardo’s example of England and Portugal by using labour as the only factor of production,Footnote 45 so that differences in technology show up as differences in the amount of output that can be obtained from one unit of labour. These differences allowed each country to exploit its comparative advantage and expand the size of the economic pie.

Differences in Resources Endowments

Given that the Ricardian model assumes labour as the only factor of production, differences in labour productivity thus provide the only possible source of comparative advantage between countries in that model. Clearly, however, differences in labour productivity are not the only source of comparative advantage. Differences in resource endowments also play a role. For example, countries that are relatively better endowed with fertile land than others are more likely to export agricultural products.

The idea that international trade is driven by differences in relative factor endowments between countries forms the core of the Heckscher-Ohlin trade model. Because this model focuses on another source of comparative advantage—factor endowments, it provides an additional explanation of trading patterns. The model rests on the theory that a country has a production bias toward, and hence tends to export, the good that intensively uses the factor with which it is relatively well endowed. However, the gains from trade in the Heckscher-Ohlin framework are fundamentally similar to those in the Ricardian model: that is, they are gains from specialization that arise because of differences between countries.

Empirical Results

While the concepts of comparative advantage and gains from trade appear straightforward, the benefits of trade are difficult to capture empirically. This is because there is considerable difficulty in translating the theories of Ricardo and Heckscher-Ohlin into forms that are testable by empirical research. Thus, very little is known about the empirical magnitudes of gains from international trade, and the mechanisms that generate these gains. In particular, limited evidence is available on how much specialization contributes to an economy’s overall prosperity.

The example of trade liberalization in Japan in 1858 provides one of the few cases in which a country moved from economic isolation (or self-sufficiency) to open trade. Using this example, Bernhofen and Brown (2005) estimate the size of gains from trade resulting from comparative advantage on national income. They found evidence that Japan’s trading pattern after opening up was governed by the law of comparative advantage and estimated the gains in real income from trade resulting from comparative advantage at 8 to 9 per cent of GDP.

The Jeffersonian trade embargo that cut off the United States from shipping between December 1807 and March 1809 provides a second test case. Here, the welfare cost to the United States of the nearly complete embargo on its international trade was estimated to be 5 percent of GDP. This cost, however, does not represent the total gains from trade because trade had already been restricted prior to the embargo (Irwin 2002).

The literature on testing and estimating Heckscher-Ohlin models is both voluminous and complex. Moreover, according to a 2008 review by the World Trade Organization most of the empirical work that attempted to test or estimate Heckscher-Ohlin models used inappropriate methods and is therefore largely irrelevant. In recent years, however, empirical work has been more about accounting for global trade flows than about testing hypotheses related to trade theories. Nonetheless, studies using appropriate methods have shown that if technological differences and home bias are included in the model and if the assumption of an integrated world is relaxed, there appears to be a substantial effect of relative factor abundance on the commodity composition of trade.

The “New” Trade Theory

The trade flow literature has highlighted the fact that traditional approaches, which attribute trade to differences between countries, have difficulties in explaining the existence and degree of trade in similar products within the same industry (i.e., what economists call “intra-industry trade”) and of trade between similar countries (in terms of technology or resources). To explain these phenomena, a “new” trade theory was needed. The best known approach is Krugman’s monopolistic competition model which provides a framework to explain these phenomena (Krugman 1979). The Krugman model employs two basic assumptions, both of which can be readily observed in the real world: “increasing returns to scale” and consumers’ “love of variety”. With increasing returns to scale (also called economies of scale), firms that double their inputs more than double their output.Footnote 46 Since goods can increasingly be produced more cheaply (i.e. more output for the same cost), producing at a larger scale becomes economically efficient. The reason why, at the extreme, economies do not rest on a single firm producing a single product is because consumers prefer to choose from different varieties for each product they buy rather than buy the same one each time. This is Krugman’s “love of variety”.Footnote 47 Consumers’ love of variety favours the existence of many small firms, each producing a somewhat differentiated product, while the exploitation of economies of scale makes it worthwhile to organize production in larger firms.

Under this approach, each firm produces a product “variety” that is “differentiated” from the varieties produced by other firms. Thus, each firm has some leeway to set prices without fear that consumers will immediately switch to a competitor for the sake of a small difference in prices. However, while these varieties are not exactly the same, they are substitutes for one another, and each firm continues to face competition from other producers in the industry. So what happens if two countries, each with identical industry technologies and factor endowments, open up to trade? According to traditional models on country differences, no trade would occur. In contrast, with differentiated goods and increasing returns to scale, trade opening enables firms to serve a larger market (and reduce their average costs) and gives consumers access to an increased range of product varieties. However, as consumers can choose among more varieties, they also become more sensitive to price. Hence, each firm can produce a larger quantity than before the trade opening (selling to both domestic and foreign markets), but each must sell their product at lower prices.

The gains from trade in such a scenario are threefold. Firms produce larger quantities and better exploit their economies of scale (“scale effect”). Consumers in both countries can choose from a wider variety of products in a given industry (“love-of-variety” effect). At the same time, in an integrated market, consumers pay lower prices (also known as a “precompetitive effect”). Because of these gains, it makes sense that similar countries trade with each other and export and import different varieties of the same good. However, while the “new” trade theory provides a framework explanation of why similar countries may find it beneficial to trade with each other, the usefulness of the theory can only be determined by the actual evidence of the predicted gains from liberalization. We thus turn to the economic literature for evidence on the various effects (e.g. scale, variety, and price), including the evidence for Canada.

Economies of Scale Results

According to “new” trade theory, firms are able to expand production within the domestic economy and enjoy lower costs through economies of scale by specializing in a variety for which they have a competitive advantage, thereby creating the conditions for intra-industry trade between countries. By engaging in international trade, firms can further expand production by offering their differentiated products to consumers in other countries, thereby lowering average costs and prices. This “economies of scale” hypothesis has been tested in the economics literature, and the evidence is mixed.

Following the conclusion of the Canada- U.S. Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA), almost all Canadian manufacturing industries exhibited substantial rationalization between 1988 and 1994. Head and Ries (1999) analyzed the impact of the CUSFTA on the size and scale of operations for 230 Canadian industries at the 4-digit SITC level. Trade liberalization was expected to have two opposing effects on the size of Canadian industries. On the one hand, a positive effect on the size of Canadian firms was expected as a result of the lowering of U.S. tariffs, due to enhanced opportunities to expand production by initiating or increasing exports to the U.S. market. In this respect, the study found that the average U.S. tariff reduction of 2.8 percent caused a 4.6‑percent scale increase among Canadian industries. On the other hand, an opposing negative effect due to increased U.S. penetration of the Canadian market was also expected. The study found that the average 5.4‑percent reduction in Canadian tariffs caused a 6.1‑percent scale decline in Canadian industries. Thus, the evidence on balance did not support an increase in the size and scale of Canadian industries as a result of Canada-U.S. trade liberalization, nor did it constitute a factor to explain the observed gains from economies of scale and specialization in many Canadian industries during the period following the introduction of the CUSFTA.

Baldwin and Gu (2006) analysed the impact of trade liberalization (the Canada-US FTA and NAFTA) on exporters and non-exporters in Canadian manufacturing industries. The analysis incorporated plant scale and production-run length both essential to achieving benefits from economies of scale—as well as product diversification. The principal conclusions suggested that trade liberalization in the form of tariff cuts reduced product diversification and reduced plant scale of non-exporters, but had little effect on their production-run length. In contrast, exporting firms reduced their product diversification and increased production-run length and plant scale when compared to non-exporters, taking advantage of the tariff cuts for further expansion.

The economies of scale benefits may thus be overstated. The likely explanation is that economies of scale at the plant level for most manufacturing firms tend to be small relative to the size of the market because most plants have already attained their minimum efficient scale. Average costs therefore seem to be relatively unaffected by changes in output; in other words, a large increase in a firm’s output does not lead to lower costs, and a large reduction in output does not lead to higher costs. When faced with competition from imports, many firms are forced to reduce output but production costs rarely rise significantly.

Variety Effects

The explanation for trade based on product differentiation suggests that many varieties of a product exist because producers attempt to distinguish their varieties from those of their competitors in order to win brand loyalty from consumers, or because consumers demand a wide spectrum of varieties. Although countries without substantial cost differences are not specialized at the industry level in international trade, they are, nonetheless, specialized at the product level within the same industry, which results in intra-industry trade.

With the opening of trade, each country increases its exports of varieties to other countries; at the same time, each faces increased competition from foreign varieties produced from abroad. As a result, a country undergoing free trade is expected to produce fewer domestic varieties due to foreign competition, but will receive a broader range of available varieties via imports. Moreover, there is a price effect associated with trade liberalization and increased competition, which lowers the price for each variety. Consequently, the sum of the varieties under freer trade would exceed the number of varieties available before the opening of trade (Feenstra, 2003).

Hillberry and McDaniel (2002) used detailed U.S. trade data to examine the extent to which the increase in NAFTA trade was associated with trade in new varieties. Their study decomposed the growth in U.S. trade with its NAFTA partners over the period 1992-2002 into price, volume, and variety effects. The variety effects are measured by the change in trade values due to trade in more or fewer goods using the Harmonized Tariff (HS) Schedule. During the 1993-2001 period, they found a 35‑percent increase in U.S. exports to Canada and a 69‑percent increase in Canadian exports to the United States. Of the measured 35 percentage point increase in U.S. exports to Canada, only 3.4 points represented trade in new goods. In other words, Canadian imports from the United States would have risen by 3.4 percentage points holding the prices and quantities of other pre-existing trade constant, due to new varieties. This represents a gain to consumers in Canada.

Chen (2006) used data on trademarks to quantitatively estimate the impact of the CUSFTA on the variety of goods available. He found that not only did the annual variety of products available to Canadians increase by 60 percent, but because of the size difference and positive relation between the size of the market and the number of varieties available in that market, Canada benefited more than the United States in terms of the number of new products available as a result of trade. The smaller Canadian economy gained access to some three times as many new U.S. varieties than U.S. consumers received from Canada.

Price Effects

A number of studies have examined the effect of foreign competition on pricing decisions by firms and concluded that trade liberalization has indeed reduced mark-ups of price over costs, although disentangling the price effect from other relevant factors has proven difficult. Badinger (2007) examined the effects on price-over-cost mark-ups using data across 18 sectors in 10 EU member states in relation to the creation of the European Union (EU) single market. After taking cyclical and technological factors into account, the study found that mark-ups in manufacturing declined by 31 per cent following integration while services mark-ups increased slightly. Badinger argued that the comparatively weak state of the single market for services and the persistence of anticompetitive strategies in certain services sectors might explain why services mark-ups did not behave as expected.

The WTO (2008) reported on several case studies that found significant price impacts arising from trade liberalization for several developing countries. For example, India posted important decreases in pricecost margins for most industries in response to a range of liberalization measures undertaken in 1991 (Krishna and Mitra 1998). Similar results were obtained for Côte d’Ivoire following the implementation of a comprehensive trade reform in 1985 (Harrison 1990). The relationship between the exposure to trade and price-cost margins at both the industry and plant levels was also examined across several developing countries—in particular, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Morocco, and Türkiye—and findings suggested that the price effects of increased import penetration were particularly strong in highly concentrated industries where firms had a degree of market power prior to trade opening (Roberts and Tybout 1991).

The trade literature therefore provides overwhelming evidence that trade liberalization fosters increased intra-industry competition. Exporting firms expand their production to serve a larger market, but given that most firms operate at an efficient plant size where output can be shifted considerably with minimal impact on costs, evidence of pronounced economies of scale is weak. Consumers, however, gain access to an increased range of product varieties following trade liberalization. Moreover, as competition in differentiated but substitutable products becomes more heated, prices fall.

The “New” New Trade Theory

The new trade theory, however, has one major drawback: it is based on the assumption of a representative firm. This contradicts the evidence generated by micro-level datasets covering firms and plants, which shows that differences among firms are crucial to understanding world trade.

Equally important, the predictions arising out of the new trade theory did not coincide with some features of trade in the real world. In particular, exporting industries do not export to all countries as implied by their theoretical cost advantage and importcompeting industries sometimes experienced productivity gains following trade liberalization, despite smaller scales of production. The analysis thus shifted from the industry level to the firm level in order to better understand trade flows (e.g., Melitz 2003).

Melitz showed that differences between firms were an additional source of comparative advantage: although, on average, no firm within a specific sector might be productive enough to export, given the dispersion of firm productivities, there might still be some firms left which would be productive enough to do so. This insight was important as it explained why countries might export (or import) in sectors where they may have a comparative disadvantage (advantage). Another major insight was that trade liberalization not only led to resource reallocations between sectors but also to allocative efficiency gains within sectors as resources are reallocated from lower-efficiency firms to higher-efficiency firms (Melitz 2003). These insights laid the foundation for the “new” new trade theory.

Under “new” new trade theory, comparative advantage can be determined at a very low level of aggregation—even within the firm at the component or task level. Such an approach can thus help us understand the increasingly granular nature of international trade and the emergence of global value chains.

Gains from Trade to Canada

The discussion thus far has addressed the broad benefits that trade brings to an economy, covering the key economic concepts, models, and theories. Clearly, many aspects of trade are intertwined. For example, liberalized trade brings about increased competition in domestic and foreign markets, increases product variety and puts downward pressure on prices. It also induces firms to specialize and produce more, but in fewer product lines, and use their particular talents, resources, and factor endowments most efficiently to their benefit. These effects, in turn, lead to supplementary benefits such as greater productivity, higher wages, and increasing prosperity. The following sections address some of these supplemental benefits of trade in the Canadian context.

Trade and Specialization in Canada

Trade in international markets is driven by the search for goods and services produced elsewhere at a relatively lower price than the opportunity cost to produce them at home. In exchange for the comparatively low priced international goods, Canada supplies goods in which it specializes. The outcome is an international division of labour that produces economic welfare gains from increased specialization. Canada stands to increase growth, firms to increase output, workers to receive higher wages, and consumers to access higher quality products at reduced prices.

Canadians have the opportunity to gain from specialization in two forms: a one-time shift in resources from less to more efficient sectors or firms, and in an ongoing form as workers, firms, and the nation as a whole focus their efforts on what they do best— and become increasingly better at doing it. One-time shifts can be understood as welfare- enhancing structural changes. Here gains derive from the movement of resources from a less to a more efficient sector. However, moving forward, while a country may specialize by moving its factors of production into more efficient sectors, it is natural that, with practice, their ability to produce the goods in which they specialize would improve with time. This type of adaptation, or learning by doing, is suggestive of the second form of specialization—ongoing or dynamic specialization. Gains in this case come from increased productivity (output per hour) through a “learning by doing” process in the same sector.

While most easily understood at the industry level (for example, the auto industry), specialization can occur at finer levels as well, such as at the firm level or plant level. Nonetheless its impact can be felt throughout the economy. Research has identified the link between specialization and trade liberalization at the plant level in Canada. Baldwin et al. (2001) found a strong relation between the export intensity of plants in manufacturing industries and their specialization following a period of increased trade liberalization in the late 1980s and implementation of the CUSFTA. The average nominal tariff (customs duties paid divided by imports) decreased from 6.5 percent in 1973 (as part of the Kennedy Round) to 1.1 percent in 1996, over which time the export intensity increased, for example, from 31 percent in 1990 to 47 percent in 1997. Likewise, commodity specialization at the plant level increased sharply with the implementation of the CUSFTA. About 30 percent of Canadian manufacturing firms that operated continuously from the early 1980s to the early 1990s reduced the diversity of their output. Within this group of firms, between 1983 and 1993 some 38 percent more firms switched from multiple-plant to singleplant firms than switched from single-plant to multiple-plant firms, further suggesting a move toward increased specialization.

Furthermore, given that Canada comprises many diverse regions, it was not surprising that the impact of increased trade liberalization and specialization yielded different impacts across the country. Brown (2008) has shown that the impact of trade liberalization on specialization was found to be greater in regions outside of urban areas and outside of Canada’s industrial centres of Ontario and Quebec. As in the case for Canada as a whole, plants with higher export intensities in these regions were found to have increased levels of specialization in the industries under investigation.

The key benefit from specialization lies in the fact that as plants specialize they become increasingly productive, either through a one-time shift in resources or through an ongoing process of learning or exploitation of scale economies. As specialization has been shown to increase at the plant-level in tandem with trade liberalization, so too has plant-level labour productivity. Trefler (2004) found that 14 percent of export-oriented industries increased productivity following the implementation of the CUSFTA; and furthermore, productivity improvements across industries were shown to grow at a compound annual rate of 1.9 percent. As a whole, labour productivity in Canadian manufacturing rose about 6 percent with the implementation of the CUSFTA—strong support for the welfareimproving nature of specialization.

Along with labour productivity, output and wage growth were also shown to increase with the implementation of the CUSFTA (Trefler 2004). On the other hand, while export-market participation in Canada is linked to higher plant specialization and productivity growth, employment growth was found to be lower in exporting firms, likely a reflection of exporters employing a more skilled, more productive workforce and operating less labour-intensive plants.

The impact of specialization on Canada’s trade has also been analyzed using computable general equilibrium (CGE) models, which have the capacity to assess the gains from trade on a per-agreement basis. Typically, CGE models estimate the economic welfare gains from FTAs under the assumption of perfect competition.Footnote 48 As such, these models are best understood as estimates of the potential economic impacts of the FTA under investigation. Nonetheless, while a number of assumptions are made in the model, the results most likely understate the gains in output and economic welfare for a given amount of trade expansion. More specifically, under the assumptions made, the removal of tariffs has less of an effect on domestic prices, as the industries are already perfectly competitive, which is not the case in reality. Therefore, although the analysis does not separate out specialization in particular from gains overall, general economic gains are estimated— of which specialization is deemed to be one component. All of the four most recent joint studies released by DFAITFootnote 49 have shown that Canada stands to gain by eliminating tariffs and increasing trade liberalization.

A discussion of the positive impacts of specialization must also take into account the effects of technology on specialization. Indeed, countries specializing in the export of goods with higher technological contents experience elevated growth rates. By exporting products with higher technological intensity, countries have typically experienced higher growth rates (Lee 2011). Industries defined as having high technological content include aircraft, pharmaceuticals, and electronics. In this regard, Canada, with its highly educated workforce, is well positioned for higher growth, provided it focuses on producing innovative, technologyintensive exports.

Trade and Domestic Competition in Canada

An often overlooked aspect of open trade is the added competition imports create in the domestic market. If not for imports, domestic producers would have a higher degree of market power. This lack of competition could allow them to set higher prices, give them less incentive to innovate, and result in lower quality goods and services being supplied to the market place. Imports thus become an important source of added competition, requiring domestic firms to compete with companies from around the world. Foreign exporting companies are usually world-class producers, offering leading-edge, high-quality, or innovative goods and services, while others offer lower-cost goods from countries with more abundant labour. The very presence of foreign competitors compels domestic firms to seek out efficiencies and cost savings and to offer higher-quality goods at the same or lower prices. This, in turn, makes domestic firms leaner, more efficient, and more competitive, thus benefiting consumers. Although additional competition may force some domestic firms to exit the marketplace, this is more than offset from the productivity growth as more efficient producers take over, and the resulting gains are passed on to consumers.

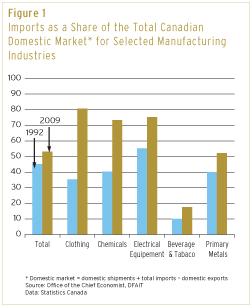

In reality, Canadian firms do face increasing competition from imports. As a percentage of the total domestic manufacturing market, imports have risen from 45 percent in 1992 to 53 percent in 2009 (latest data available). In some manufacturing sectors, such as clothing, chemicals and electrical equipment, this trend has been even more pronounced, while in others, such as beverages and tobacco, import penetration is less striking. Research indicates that the increased influence of imports has raised the competitiveness of Canadian manufacturers.

Figure 1

Imports as a Share of the Total Canadian Domestic Market* for Selected Manufacturing Industries

* Domestic market = domestic shipments + total imports – domestic exports

Source: Office of the Chief Economist, DFAIT

Data: Statistics Canada

Figure 1 Text Alternative

| 1992 | 2009 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 45.2% | 53.1% |

| Clothing | 35.3% | 80.7% |

| Chemicals | 40.4% | 73.4% |

| Electrical Equipment | 55.3% | 75.2% |

| Beverage & Tabaco | 10.0% | 17.6% |

| Primary Metals | 40.0% | 52.2% |

The impact of increased competition in Canada can be seen following the implementation of the CUSFTA and NAFTA. Increased competition from imports caused the number of firms in the domestic economy to decrease as smaller and less efficient firms closed, allowing more efficient firms to expand and become even more productive. In the six years following the CUSFTA, the number of manufacturing plants declined by 21 percent while output per plant in Canada increased by 34 percent. This reduction in number of firms was found to be largely induced by the reduction in tariffs (Head and Reis 1999).

The notion that increased imports from trade liberalization results in the closing of some domestic firms may at first appear to be a negative outcome. But it is important to realize that this is one of the main mechanisms by which increased competition makes the domestic market more efficient: firms that were compelled to shut down did so because they could not compete with the quality or price of foreign imports, while those domestic firms that remained were more efficient and better able to face the increased competition from abroad. In this way, imports cause a reallocation of domestic resources to more efficient uses. Plant turnover (closing of some companies and opening of others) contributed between 15 percent to 20 percent of manufacturing productivity growth during the 1988-1997 period (Baldwin and Gu 2002).

Not only does competition force out less productive plants, but the surviving firms are also compelled to become even more productive in domestic economy. Baldwin and Gu (2009) looked at 7,000 Canadian manufacturing plants for the period 1984 to 1990 and found that plants in industries with the largest tariff changes also experienced the largest increases in product-run length, and increased plant size. This was due both to increased competition from imports and from gains in exporting accruing from greater access to the U.S. market.

Studies from other countries support these findings. For example, Liu (2010) showed that greater import competition in the United States led multi-product firms to drop peripheral products and focus on core production. Gibson and Harris (1996) investigated the effect of trade liberalization on manufacturing in New Zealand and found that liberalization caused smaller-sized, higher-cost plants to close, while low-cost specialized plants were more likely to survive. In Chile, Pavcnik (2000) showed that the trade liberalization undertaken in that country in the late 1970s and early 1980s resulted in plant level productivity improvements that were mainly due to the reshuffling of resources and output from less to more efficient producers.

CGE models can also be used to show the impact of imports on competition. For example, Cox and Harris (1985) show that by incorporating scale economies, imperfect competition, and capital mobility into these models, the estimated gains from trade to Canada under the CUSFTA increase by a significant factor (in the order of 8 to 10 percent of GNP) through rationalization of industries, greater production runs, lower price-cost mark-ups, and increases in factor productivity.

Imports also encourage innovation in an economy, first, by obliging domestic producers to innovate to improve their products and production processes in order to compete with foreign goods and services; and second, the imports themselves produce spill-over effects by introducing foreign technology and ideas into the domestic marketplace to consumers and producers alike. Unfortunately there is little empirical evidence on the impact of imports in Canada in this regard, but there are some international studies that quantify the spill-over effect. One such study examined the impact of Chinese imports on a sample of 200,000 European firms and found that competition from Chinese imports led to technology upgrading within firms as well as resource reallocation to technologically intensive plants. Between 15 to 20 percent of technology upgrading in the EU between 2000 and 2007 was attributed to competition from Chinese imports (Bloom et al. 2009). A link between imports and innovation was also found in Mexican plants. Teshima (2008) documents that sectors affected by greater tariff reductions were induced to increase R&D expenditures. However, in that case, R&D expenditures were more likely to go toward upgrading processes as opposed to products, suggesting that competition from imports generated greater incentives to increase production cost efficiencies rather than to create new products or increase product quality.

Trade and Productivity in Canada

Productivity performance is central to economic growth, competitiveness, and standards of living. This section examines two avenues by which opening trade has contributed to improvements in Canadian productivity: improvements in allocative efficienciesFootnote 50 and improvements in productivity efficiencies.Footnote 51

Open economies tend to grow faster than closed economies because reduced barriers to trade improve productivity performance and support capital accumulation. For example, a recent study based on results from 14 OECD countries and 15 manufacturing sectors found that an increase in openness by one percentage point increased productivity in manufacturing by an average 0.6 percent (Badinger and Breuss 2008).

One of the best-known examples of open trade leading to improved productivity performance is the North American Auto Pact of 1965. Prior to the signing of the Auto Pact, the Canadian automotive industry produced most car models for Canadian consumers and the U.S. automotive industry did likewise for U.S. consumers. Since the Canadian auto market was much smaller than the U.S. market, the Canadian auto sector was at a substantial disadvantage in terms of scale of production in the Canadian market, and productivity in the sector was about 30 percent below that of the U.S. auto sector. The establishment of a free trade area for automotive products under the Auto Pact allowed manufacturers to consolidate the production of car models in one partner country, and export those models to consumers in the other partner country. This rationalization of production resulted in the reduction of the number of car models assembled in Canada. However, by concentrating resources into fewer models, total Canadian auto production actually increased while average costs for auto production decreased. Canadian auto products became much more competitive compared to the pre-Auto Pact era and exports of Canadian auto products to the United States surged. Moreover, a few years after the inception of the Auto Pact, Canada’s productivity gap with U.S. auto industry had virtually disappeared (Wonnacott and Wonnacott 1982).

Other examples of gains in efficiency arising from increased intra-industry trade include empirical research into the effects arising from the implementation of the CUSFTA conducted by Baldwin, Beckstead and Caves (2001), Baldwin, Caves, and Gu (2005), and Baldwin and Gu (2006), who documented a dramatic reduction in the number of manufacturing products produced in Canada following the implementation of the CUSFTA in 1989. In particular, Baldwin, Caves, and Gu (2005) report that the decrease in the number of products produced in Canada was accompanied by substantial increases in production runs for individual products.

Moreover, because of productivity differences between firms, when trade barriers are removed (or reduced), more productive firms tend to thrive and expand, while less productive firms contract or possibly exit. This generates another type of allocative efficiency gain known as the “reallocation” effect. In essence, market share is reallocated from less efficient firms to more efficient firms—with the result that overall efficiency in the industry improves.

Using firm-level data, Lileeva and Trefler (2010) examined the significance of this “reallocation” effect in raising Canada’s overall manufacturing productivity in the wake of the Canada- U.S. FTA. Analysing plantlevel exports between 1984 and 1996, they found that as the United States lowered its tariffs against imports from Canada under the CUSFTA, Canadian exporters grew by exporting to the U.S., thereby raising overall productivity. A market share-shift analysis showed that this raised average manufacturing productivity by 4.1 percent.

At the same time, corresponding Canadian tariff cuts pressured some Canadian firms to contract and even exit in the face of foreign competition. This selection effect also generated overall productivity gains in the Canadian manufacturing sector since the contracting and exiting plants were substantially less efficient than the average Canadian firms. Trefler (2004) estimated that this selection effect increased overall Canadian manufacturing productivity by an estimated 4.3 percent.

Thus, the allocative efficiency gains via reallocation and the selection effects induced by the CUSFTA combined to generate a productivity gain of 8.4 percent (i.e. 4.3 percent plus 4.1 percent) for Canadian manufacturing.

Beyond those gains associated with differences in efficiency between firms, gains also arise from within individual firms themselves. As exporting firms become larger because of open trade, it becomes attractive for some firms to invest in innovation and technology, skills and knowledge, thereby raising their profits and productivity. The development of new products and processes, and adapting these to foreign markets, also involves substantial fixed costs, so only the larger, integrated markets can support the sales volumes needed to justify incurring the high fixed costs of innovation and investment. While adapting to local conditions in foreign markets is often a dynamic and timeconsuming learning process, it is by learning through exporting that many exporting firms improve their productivity.

For evidence on within-firm productivity gains, Lileeva and Trefler (2010) divided 5,000 firms that had not exported prior to the CUSFTA into two groups: those that started exporting in the CUSFTA implementation period and those that did not. The study found that the CUSFTA raised the productivity of new exporters by 15.3 percent, and furthermore that these new exporters accounted for 23 percent of Canadian manufacturing output, and were therefore responsible for raising Canada’s overall manufacturing productivity by 3.5 percent (i.e. 15.3 percent multiplied by 0.23). In addition to these new exporters, existing exporters, or firms that had already been exporting to the United States prior to the CUSFTA, also responded to improved market access by increasing their exports: this contributed to an overall 1.4‑percent productivity growth for Canadian manufacturing. Finally, productivity gains came from increased imports of intermediate inputs imported from the United States under the CUSFTA, which contributed an additional 0.5‑percent increase in total productivity to Canada’s manufacturing industry.

The gain from the CUSFTA on overall Canadian manufacturing productivity is therefore 13.8 percent—the sum of the allocative gains (between firms) and the productive gains (within firms)—a remarkable trade-related achievement.

| Allocative efficiency gains (between firms) | Growth of most productive exporters | 4.1% |

|---|---|---|

| Contraction and exit of least productive exporters | 4.3% | |

| Productive efficiency gains (within firms) | New exporters invest in raising productivity | 3.5% |

| Existing exporters invest in raising productivity | 1.4% | |

| Improved access to U.S. intermediate inputs | 0.5% | |

| Total | 13.8% | |

Sources: Trefler (2004) and Lileeva and Trefler (2010)

Trade and Prosperity in Canada

Trade and prosperity go hand-in-hand. Trade allows consumers to buy products and services to which they would not otherwise have access. It is as a result of international trade that Canadians are able to eat fresh fruit and vegetables in the winter, have access to coffee and chocolate, and to the choice of more than 300 models of carsFootnote 52 and 197 models of cell phone.Footnote 53 Because of trade, almost everything that Canadians consume daily is cheaper than it otherwise would be, stretching Canadian incomes even further.

Through higher wages, trade puts more money in the pockets of Canadians to spend on necessities like food, shelter, and government services like education and healthcare or on discretionary items like flat-screen TVs and the occasional vacation. Because trade encourages companies and workers to specialize in what they do best, to innovate, and to grow large by serving global markets, the productivity of firms improves, which in turn drives up wages for workers and increases Canada’s prosperity. The end result is increased standards of living.

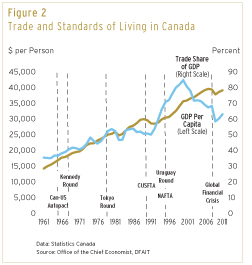

Figure 2

Trade and Standards of Living in Canada

Figure 2 Text Alternative

| Trade Share of GDP | GDP Per Capita | |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 41.07% | $19,930 |

| 1972 | 42.24% | $20,773 |

| 1973 | 44.72% | $21,950 |

| 1974 | 48.69% | $22,444 |

| 1975 | 46.44% | $22,522 |

| 1976 | 44.82% | $23,384 |

| 1977 | 46.34% | $23,911 |

| 1978 | 49.49% | $24,610 |

| 1979 | 52.95% | $25,295 |

| 1980 | 54.02% | $25,511 |

| 1981 | 52.79% | $26,081 |

| 1982 | 47.12% | $25,036 |

| 1983 | 47.30% | $25,463 |

| 1984 | 53.40% | $26,690 |

| 1985 | 53.90% | $27,712 |

| 1986 | 54.39% | $28,102 |

| 1987 | 52.15% | $28,914 |

| 1988 | 52.41% | $29,961 |

| 1989 | 51.06% | $30,199 |

| 1990 | 51.24% | $29,804 |

| 1991 | 50.54% | $28,820 |

| 1992 | 54.28% | $28,731 |

| 1993 | 60.15% | $29,081 |

| 1994 | 66.57% | $30,146 |

| 1995 | 71.19% | $30,674 |

| 1996 | 72.48% | $30,846 |

| 1997 | 76.74% | $31,832 |

| 1998 | 80.58% | $32,862 |

| 1999 | 82.44% | $34,399 |

| 2000 | 85.17% | $35,864 |

| 2001 | 81.11% | $36,112 |

| 2002 | 78.40% | $36,771 |

| 2003 | 72.12% | $37,124 |

| 2004 | 72.38% | $37,922 |

| 2005 | 71.71% | $38,697 |

| 2006 | 69.58% | $39,386 |

| 2007 | 67.80% | $39,820 |

| 2008 | 68.78% | $39,626 |

| 2009 | 58.96% | $38,059 |

| 2010 | 60.7% | $38,826 |

It is hardly coincidental that the Canadian standard of living and Canada’s openness to international trade (both exports and imports) are closely linked. Each incremental opening to international trade has been linked to further improvements in the Canadian standards of living (Figure 2). This relationship between trade and improved standards of living has been formally tested in a large project on understanding economic growth undertaken by the OECD. Using the data from 21 advanced countries over nearly 30 years, the OECD reported that, controlling for other factors, every 10‑percentage point increase in trade exposure (as measured by trade share of GDP) contributes a 4‑percent increase in GDP per capita. Employing a different methodology than that used in the OECD, Frankel and Romer (1999) found further evidence supporting the link between international trade and economic growth for developing countries in particular. Here, a 1‑percent rise in trade share produced a rise in per capita incomes of between 0.8 and 2.0‑percent. This finding suggests that openness to trade is a key factor in economic development.

Trade and Wages

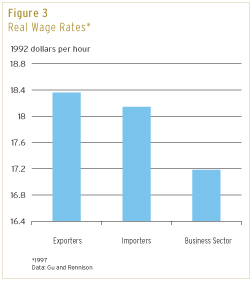

Figure 3

Real Wage Rates (1997)

Data: Gu and Rennison

Figure 3 Text Alternative

Real Wage Rates (1997) in 1992 dollars per hour

- Exporters: $18.36

- Importers: $18.14

- Business Sector: $17.18

Trade has a significant impact on workers through its effect on wages. While some firms may shrink or exit when faced with the additional competition that trade brings, others will meet the challenge. Research shows that the latter will be the most productive firms. In addition, as these firms grow and expand abroad they will become even more productive and innovative, allowing them to pay higher wages while also increasing their employment. This was the case in Canada following the implementation of both the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement and NAFTA. Gu and Rennison (2006), for example, find a significant and growing wage premium in traded sectors (both exports and imports) compared to the economy overall once the public sector is removed from consideration.

Because exporting firms are more productive, they are thought to pay their employees higher wages. Indeed, Bernard and Jensen (1999) estimated that U.S. exporters pay, on average, wages that were 9.3 percent higher than those paid by non-exporters. Similarly, a 25‑percent export wage premium was found by Arnold and Hussinger (2005) for German manufacturers. However, other factors, such as manufacturing plant size, capital intensity, degree of foreign-control, and multi-unit firm status, as well as certain individual worker characteristics, are also factors positively associated with higher wages. A recent paper by Breau and Brown (2011) performed plant-level regressions controlling for such factors. Canadian exporters paid wages that were, on average, about 14 percent higher than those paid by nonexporters; however, this wage premium fell to slightly over 6 percent, once plant characteristics were taken into account and was further reduced to slightly under 6 percent once controls for indivual worker characteristics were included.

Conclusions

International trade is driven by the search for goods and services produced at relatively lower prices than the opportunity cost to produce them domestically. As trade is liberalized, competition for markets heats up. Except for those firms (and their employees) that are the least productive, the increased competition is beneficial. Competition from imports prevents firms that hold power in domestic markets from over-charging, or under-producing, for the market. More importantly, competition from imports causes domestic firms to realign their resources, to drop less-profitable lines of production, and to specialize in one variety (or on a “differentiated” product) for which the firm has a comparative advantage. The outcome is an international division of labour and increased economic welfare.

This was the case following the CUSFTA and NAFTA. Economic evidence suggests that increased competition from imports induced a number of smaller and less-efficient firms to close and allowed more efficient firms to expand. At the plant level, Canadian plant sizes increased and production runs lengthened due to gains accruing from greater exports to the United States.

Moreover, following both agreements, Canadian consumers were introduced to a greater variety of products than before. One estimate found that the agreements increased the annual variety of products available to Canadians by 60 percent, which was about three times as great as the new varieties introduced into the United States from Canada. A separate study found that roughly 10 percent of the increase in U.S. exports to Canada represented trade in new goods.

As firms narrow production lines, concentrate on differentiated products, extend production-run lengths and face new entrants in their markets, they are induced to compete in prices as well. Evidence suggests that trade liberalization also brought about reduced mark-ups over costs—to the benefit of consumers.

Liberalized trade is also expected to have an impact on productivity levels. Between 1984 and 1996, following the CUSFTA, Canadian manufacturing productivity rose by an estimated 13.8 percent. The expansion of exports and realignment from lessefficient to more-efficient producers following that agreement accounted for about 60 percent of the overall increase in productivity, or 8.4 percentage points. Better access to intermediate products combined with increased productivity from new and existing exporters contributed the remaining 5.4 percentage points in improvement of productivity.

Empirical evidence strongly supports the observation that firms that export pay higher wages. Higher wages (wage premiums) are induced by increased productivity, and Canadian exporters are indeed productive, paying wage premiums compared to non-exporters.

Overall, an open trade policy leads to higher wages for employees, lower prices and greater variety for consumers, and greater productivity in business operations through less costly inputs and more efficient and longer production runs. The increased level of competition also creates an environment in which firms are facing incentives to innovate and control costs—to the benefit of all Canadians.

Bibliography

Arnold, J.M. and K. Hussinger (2005), “Export Behaviour and Firm Productivity in German Manufacturing: A Firm-Level Analysis,” Review of World Economics, 141-2: 219-243.

Badinger, Harald (2007), “Has the EU’s Single Market Programme Fostered Competition? Testing for a Decrease in Mark-up Ratios in EU Industries,” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69, 4: 497-519.

Badinger, Harald and Fritz Breuss (2008), “Trade and Productivity: An Industry Perspective,” Empirica, Springer, vol. 35 (2): 213-231.

Baldwin, John R., Desmond Beckstead, and Richard Caves (2001), “Changes in the Diversification of Canadian Manufacturing Firms (1973-1997): A Move to Specialization,” Statistics Canada, No. 11F0019 No. 179, 2001.

Baldwin, John R., Richard Caves, and Wulong Gu (2005), Responses to Trade Liberalization: Changes in Product Diversification in Foreign- and Domestic-controlled Plants. Economic Analysis (EA) Research Paper Series. Catalogue No. 11 F0027MIE2005031. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Baldwin, John R. and Wulong Gu (2002), “Plant Turnover and Productivity Growth in Canadian Manufacturing,” Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 15, Issue 3, June: 417-465.

Baldwin, John R. and Wulong Gu (2006), “The Impact of Trade on Plant Scale, Production-Run Length and Diversification”, Statistics Canada, Economic Analysis Research Paper Series.

Baldwin, John R. and Wulong Gu (2009), “The Impact of Trade on Plant Scale, Product –run length and Diversification,” Producer Dynamics: new evidence from Micro Data, NBER chapter 15.

Bernard, Andrew B. and J. Bradford Jensen (1999), “Exceptional Exporter Performance: Cause, Effect, or Both?” Journal of International Economics, 47, I: 1-25.

Bernhofen, Daniel M. and John C. Brown (2005), “An Empirical Assessment of the Comparative Advantage Gains from Trade: Evidence from Japan,” American Economic Review, 95, I: 208-225.

Bloom, Nicholas, Mirko Draca, and John Van Reenen (2009), “Trade Induced Technical Change? The Impact of Chinese Imports on Innovation, Diffusion and Productivity,” NBER Working Paper No.16717, Cambridge, MA.

Breau, Sébastien and W. Mark Brown (2011), “Global Links: Exporting, Foreign Direct Investment, and Wages: Evidence from the Canadian Manufacturing Sector,” The Canadian Economy in Transition Series, Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 11-622 – No. 021, August 2011.

Brown, W. Mark (2008), “Trade and the Industrial Specialization of Canadian Manufacturing Regions 1974-1999,” International Regional Science Review, 31, 2: 138-158.

Chen, Shenjie (2006), “The Variety Effects of Trade Liberalization,” in NAFTA@10, John Curtis and Aaron Sydor Editors, Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, 2006: 43-72.

Cox, David and Richard Harris (1985), “Trade Liberalization and Industrial Organization: Some Estimates for Canada,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 93, No. 1, Feb: 115-145.

Feenstra, Robert C. (2003), Advanced International Trade: Theory and Evidence, Princeton University Press, Chapter 5.

Frankel, Jeffrey A. and David Romer (1999), “Does Trade Cause Growth?” American Economic Review, Vol. 89, No. 3. June 1999.

Gibson, John and Richard Harris (1996), “Trade Liberalisation and Plant Exit in New Zealand Manufacturing,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 78, No. 3, pp.521-529.

Gu, Wulong and Lori Rennison (2006), “The Effect of Trade on Productivity Growth and the Demand for Skilled Workers in Canada,” in NAFTA@10, John Curtis and Aaron Sydor Editors, Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, 2006: 105-124.

Harrison, Ann E. (1990), “Productivity, Imperfect Competition and Trade Liberalization in Côte d’Ivoire,” Policy Research Working Paper No 451, The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Head, Keith and John Ries (1999), “Rationalization Effects of Tariff Reductions,” Journal of International Economics, 47, 2: 295–320.

Hillberry, H. Russell and Christine A. McDaniel (2002), “A Decomposition of North American Trade Growth Since NAFTA”, International Economic Review, May/June 2002, U.S. International Trade Commission.

Irwin, Douglas A. (2002), “The Welfare Costs of Autarky: Evidence from the Jeffersonian Trade Embargo, 1807-1809,” NBER Working Paper No. 8692, Cambridge, MA.

Krishna, Pravin and Devashish Mitra (1998), “Trade Liberalization, Market Discipline and Productivity Growth: New Evidence from India,” Journal of Development Economics, 34, 1-2: 115-136.

Krugman, Paul (1979), “Increasing Returns, Monopolistic Competition, and International Trade,” Journal of International Economics 9, 4: 469-479.

Lee, Jim (2011), “Export Specialization and Economic Growth Around the World,” Economic Systems, 35: 45-63.

Lileeva, Alla and Daniel Trefler (2010), “Improved Access to Foreign Markets Raises Plant-Level Productivity … for Some Plants,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, CXXV, 3: 1051-1099.

Lui, Runjuan (2010), “Import Competition and Firm Refocusing,” Canadian Journal of Economics, Vol. 43, No. 2, May: 440-466.

Melitz, Marc J (2003), “The Impact of Trade on Intra-industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity,” Econometrica, Vol. 71, No. 6, November: 1695-1725.

Pavcnik (2000), “Trade Liberalization, Exit, and Productivity Improvements: Evidence from Chilean Plants,” NBER Working Paper No. 7852, Cambridge, MA.

Roberts, Mark J. and James R. Tybout (1997), “The Decision to Export in Colombia: An Empirical Model of Entry with Sunk Costs,” American Economic Review, 87: 545-564.

Teshima, Kensuke (2008), “Import Competition and Innovation at the Plant Level: Evidence from Mexico,” Columbia University Mimeo.

Trefler, Daniel, “The Long and Short of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 94 No. 4, September 2004.

Wonnacott, Paul and Ronald J. Wonnacott (1982), “Free Trade Between the United States and Canada: Fifteen Years Later,” Canadian Public Policy VIII (Supplement): 412-427.

World Trade Organization (WTO) (2008), “Trade in a Globalizing World”, Chapter II in World Trade Report 2008 — Trade in a Globalizing World, Geneva.

- Date Modified: