Voices at Risk: Canada’s Guidelines on Supporting Human Rights Defenders

On this page

- Introduction

- 1. Human rights context

- 2. Canada’s approach to supporting human rights defenders internationally

- 3. Guidelines to support human rights defenders for diplomatic missions

- 3.1 Mapping, information gathering and reporting

- 3.2 Relationship building, regular contact and information exchange with human rights defenders…

- 3.3 Enhancing visibility for human rights defenders

- 3.4 Recognizing efforts through awards

- 3.5 Building capacity and providing funding to human rights defenders

- 3.6 Fostering effective human rights defenders’ support networks

- 3.7 Engaging with local authorities

- 3.8 Cooperating with key regional and international actors

- 3.9 Attending trials and hearings and visiting detained human rights defenders

- 3.10 Making public statements and using social media

- 3.11 Supporting emergency assistance needs

- 3.12 Promoting responsible business conduct

- 4. Specific cases with a Canadian nexus

- 5. Implementation

- 6. Annexes

- 6.1 Women human rights defenders

- 6.2 LGBTI human rights defenders

- 6.3 Indigenous human rights defenders

- 6.4 Land rights and environmental human rights defenders

- 6.5 Disability rights defenders

- 6.6 Youth human rights defenders

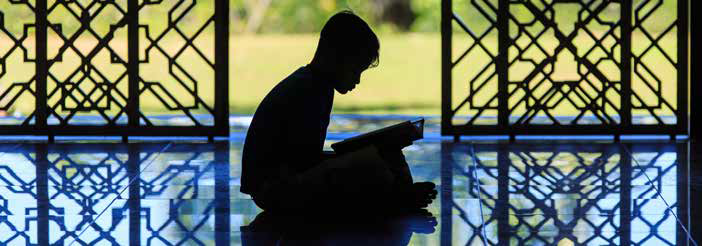

- 6.7 Freedom of religion or belief human rights defenders

- 6.8 Journalists

- 6.9 Human rights defenders in online and digital contexts

- Appendix A: Privacy Considerations

- Appendix B: Existing Guidelines on Human Rights Defenders

Introduction

Canadians care about human rights. They expect their government to help build respect for human rights at home and around the world.

Promoting respect for human rights is at the heart of Canada’s international policies and engagement. Canada works multilaterally, bilaterally and through international trade, development and consular assistance, to strengthen the rules-based international order that protects universal human rights, democracy and respect for the rule of law. The Government of Canada pursues these objectives by working closely with other governments, Indigenous peoples, civil society, international organizations and the private sector. Canada will continue to seek the promotion and protection of universal human rights, and to support those who work for their realization. All individuals shall have the equal protection of the law, including the universal rights to exercise their freedom of opinion and expression, peaceful assembly and association, online as well as offline.

Canada recognizes the key role played by human rights defenders in protecting and promoting human rights and strengthening the rule of law, often at great risk to themselves, their families and communities, and to the organizations and movements they often represent. Canada has a strong tradition of supporting these brave people in communities around the world as they hold governments and companies to account and keep respect for human rights alive. These are individuals who stand up for others who face discrimination — often at their peril.

Canada’s Guidelines on Supporting Human Rights Defenders (the Guidelines) is a clear statement of Canada’s commitment to supporting the vital work of human rights defenders. The Guidelines outline Canada’s approach and offer practical advice for officials at Canadian missions abroad and at Headquarters to promote respect for and support human rights defenders. Missions should do their utmost to implement these Guidelines, recognizing that each approach should be tailored to local contexts and circumstances, and respond to the specific needs of individual human rights defenders. Section 4 of these Guidelines provides detailed guidance for Canada’s diplomatic missions.

The Guidelines reflect the experience gained over the years by Canadian representatives working across the globe to support human rights defenders and are informed by the work and advice of Canadian civil society organizations. The 2016 edition of the Guidelines has been updated to reflect Canada’s feminist foreign policy, including an understanding that human rights defenders—and in particular women and LGBTI human rights defenders—have intersecting identities (such as race, age, disability, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and gender identity), and experience numerous and concurring forms of discrimination, harassment and marginalization. Specific guidance has been developed to better recognize the different experiences lived by human rights defenders belonging to one or more specific identifiable groups that face discrimination, in various contexts, including: women human rights defenders, LGBTI human rights defenders, Indigenous human rights defenders, land and environment rights defenders, disability rights defenders, youth human rights defenders, freedom of religion or belief human rights defenders, journalists, and human rights defenders in online and digital contexts (see Section 7 - Annexes). These groups are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive, nor hierarchical. The annexes should be read in conjunction and complementarity to one another, and to the guidance provided in the core document, recognizing that human rights defenders often have multiple and overlapping identities and experiences.

The Guidelines reflect Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy, which recognizes the particular importance of supporting the protection of women’s human rights defenders, as well as Canada’s Policy for Civil Society Partnerships for International Assistance—A Feminist Approach, which recognizes the need to facilitate a safe and enabling environment for civil society, including human rights defenders and women’s, LGBTI, and youth organizations and networks, as well as representatives of Indigenous peoples. The Guidelines also reinforce the Government of Canada’s expectation that Canadian companies operating abroad have a responsibility to respect human rights.

Canada’s approach to supporting human rights defenders is based on these key values:

- Human rights are universal and inalienable; indivisible; interdependent and interrelated.

- Do no harm—the safety and privacy of the human rights defenders are paramount.

- Consent—actions on specific cases should be taken with the free, full, and informed consent of the human rights defenders in question, wherever possible, or of their representatives or families, in the alternative.

The ultimate goal is to ensure that Canada continues to provide effective support to people around the world who work for human rights, by helping human rights defenders to be more effective advocates, ensuring they are able to carry out their work in a safe and enabled environment, and protecting them from harm. Human rights defenders help defend the vital and fundamental human rights that we all enjoy. We need to continue to be strong advocates for them.

1. Human rights context

1.1 Who are human rights defenders?

The term Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) refers to people who, individually or with others, act to promote or protect human rights through peaceful means, such as by documenting and calling attention to violations or abuses by governments, businesses, individuals or groups.

HRDs are identified above all by what they do. Many defenders do not identify themselves as such. Many begin by merely attempting to exercise their rights in the face of adversity and then take on an advocacy role. HRDs can be individuals of any background – community members, Indigenous leaders, workers, activists, students, business executives, journalists, and whistleblowers, for example. They can act as HRDs in a professional or non-professional context, and on a paid or voluntary basis. Whether they have notoriety is irrelevant. What matters is whether and how those individuals act to support human rights.

HRDs sometimes focus on specific categories of rights or the rights of specific persons. They may seek to promote and protect civil and political rights, as well as economic, social and cultural rights. They may also promote and protect the rights of specific groups: women, children, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) persons, persons with disabilities, Indigenous peoples, refugees, migrants and internally displaced persons, individuals belonging to religious, ethnic or linguistic minorities, or focus on specific themes such as labour rights, or rights related to land, natural resource management and the environment, and democratic governance, for example. They can also raise concerns about emerging issues, including in the areas of digital technologies and online activity.

HRDs must exercise their activities peacefully. Individuals or groups, who commit, propagate or condone acts of violence or discrimination—including through advocacy of hatred and incitement to violence—are not considered HRDs.

1.2 Role of human rights defenders in improving human rights

HRDs play an important role in the promotion and protection of human rights at the local, national, regional and international levels, including by collecting and disseminating information, by calling attention to violations by states of their obligations to promote and respect human rights, and by highlighting abuses of human rights by other actors.

HRDs are active in every part of the world: in states divided by armed conflict as well as in stable states; in states that are non-democratic as well as those that adhere strongly to democratic principles; and in both developing and developed economies. They are also active in transnational spaces through online and digital activities.

The work of HRDs can bring many benefits to their communities, from helping to make governments more accountable and fighting impunity, to protecting vulnerable communities from harm and providing assistance to victims, to enhancing respect for rights related to economic participation. Their work is a fundamental pillar of the international human rights system and is critical to inclusive, safe and prosperous societies.

“When human rights defenders are threatened the principles of the United Nations are under attack. Human rights defenders are a great asset in enhancing our work to sustaining peace and sustainable development. These individuals and organizations are often the first to set off alarm bells and provide us with early warnings of impending crises, and they are key actors in the development of potential solutions in all areas of life. Let us embrace and support human rights defenders everywhere so they can continue to do their essential work.” Remarks by the UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres to the General Assembly, 18 December 2018

1.3 Risks and threats to human rights defenders

The work of HRDs and civil society organizations can be dangerous. They are often subject to intimidation, threats, job loss and restrictions on their freedoms of movement, expression, association and assembly. In many countries, HRDs are increasingly at risk of violence, harassment and human rights abuses and violations including enforced disappearance, extrajudicial killing, arbitrary arrest or detention, unlawful imprisonment, torture, sexual violence and unfair trials. Individuals from vulnerable and marginalized groups are particularly at risk, including women, LGBTI people, and Indigenous peoples. For example, the challenges and threats faced by women HRDs may be greater and different in nature than those faced by male HRDs. HRDs with intersecting identities experience heightened and specific risks. The Annexes provide additional information on the risks faced by different groups.

In both democratic and non-democratic states, many governments seek to stifle civil society and jeopardize the work of HRDs, both online and offline, including by: enacting new legislation and regulations that limit the full enjoyment of fundamental rights and freedoms; imposing restrictions on civil society or media organizations, such as by taking away their legal status; criminalizing peaceful social protests; discriminating openly against individuals from marginalized and vulnerable groups; and using increasingly harsh tactics of intimidation, unlawful and arbitrary surveillance, threats and reprisals.

Non-state actors, such as businesses, individuals and groups, including criminal organizations or terrorist groups, may also target HRDs because of their work, often with the approval of governments, whether tacit or explicit. For example, in contexts where the activities of private enterprises are challenged by community members or corruption is being exposed, HRDs may be subject to targeted attacks to silence opposition and halt their work.

The impact of such violations and abuses on the individuals themselves, on their families and communities, and on respect for human rights and the rule of law overall, is profound. Attacks against HRDs are attacks against everyone’s human rights.

“Since the adoption of the Declaration (on human rights defenders in 1998), at least 3,500 human rights defenders have been killed for their role in the struggle for human rights. Countless other human rights defenders have suffered all forms of indignities and abuses.” Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, 23 July 2018

According to Front Line Defenders Global Analysis 2018, 321 human rights defenders in 27 countries were targeted and killed for their work in 2018. More than three-quarters of these were defending land, environmental or Indigenous peoples’ rights, often in the context of extractive industries and mega projects. At least 49% of those killed had previously received a specific death threat. In addition to physical attacks, the report highlights a continuing trend of restrictive legislation aimed at stifling human rights defenders.

1.4 International Framework

The main international documents and instruments for the protection of HRDs include:

- the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a foundational document to which all UN members subscribe;

- the Core International Human Rights Instruments, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and their monitoring bodies; and

- the Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (also known as the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders).

Core International Human Rights Treaties and Monitoring Bodies

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

- Human Rights Committee

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR)

- International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD)

- Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD)

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

- Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

- Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT)

- Committee Against Torture (CAT)

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

- Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)

- Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)

- International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (CPED) *

- Committee on Enforced Disappearances

- International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (ICMW)*

- Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (CMW)

* Canada has not ratified these treaties.

The Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, adopted by consensus by all UN member States in 1998, is a key milestone in recognizing the important work carried out by HRDs, as well as the need to create a safe and enabling environment, and to provide them with protection. It recognizes the legitimacy of their activities, defining HRDs by what they do—promoting and protecting human rights and fundamental freedoms through peaceful means—regardless of sex, gender, age, race, colour, religion, national or social origin, or any other grounds of discrimination. It also sets out that internationally recognized human rights, such as the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association, are cornerstone principles of their work.

“Everyone has the right, individually and in association with others, to promote and to strive for the

protection and realization of human rights and fundamental freedoms at the national and international levels.” UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, article 1

The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders is mandated to work with countries in support of the implementation of the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders and to gather information on HRDs around the world. The Special Rapporteur presents annual reports to the UN Human Rights Council and the General Assembly on particular topics, undertakes country visits and raises individual cases of concern with governments. Canada strongly supports the work of the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders.

2. Canada’s approach to supporting human rights defenders internationally

Canada’s support for HRDs takes many forms and responds to changing needs:

- Working in multilateral forums to strengthen international rules and norms, and advocate for open civic space and human rights;

- Engaging with local authorities through bilateral diplomacy;

- Leveraging partnerships with other countries, civil society, Indigenous peoples and the private sector, including Canadian business interests abroad, and building capacity, including through funding for human rights organizations; and

- Promoting responsible business conduct.

Global Affairs Canada works with HRDs and local, regional and international human rights organizations through its officials at Headquarters and at its missions abroad. This active cooperation helps to inform Canada’s human rights policies, priorities and activities internationally.

A state’s ability to address each HRD case through its diplomatic corps can be constrained by various factors. This is why Canada works collaboratively with a variety of partners and stakeholders in support of HRDs.

2.1 Engaging through multilateral institutions

Through its engagement in multilateral forums, Canada helps to strengthen and maintain respect for the rules-based international order and the promotion of human rights. Canada also uses these fora to advocate strongly for the protection of HRDs. This includes support to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and efforts to ensure that civil society and representatives of Indigenous peoples have the opportunity to participate in multilateral human rights forums as partners and stakeholders in constructive dialogue, without fear of reprisals.

The UN’s human rights institutions play a vital role in setting standards, monitoring conditions and encouraging and supporting states to meet their obligations. One of the key UN institutions is the Human Rights Council (HRC). Through the HRC’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR) mechanism, Canada makes constructive recommendations to all UN Member States to improve human rights promotion and protection, and to fulfill the commitments they made previously through the UPR or on the basis of their treaty obligations. The UPR also provides an opportunity for Canada to assess its human rights situation, through identifying strengths and recognizing challenges where improvements are needed.

Canada supports resolutions at the HRC and at the UN General Assembly that seek to promote and protect the rights of HRDs. Moreover, Canada engages in dialogue and delivers statements in those fora to express its support for HRDs. Canada also supports the active participation of civil society organizations and HRDs at the UN, and seeks areas for collaboration.

In addition, Canada actively participates in the Community of Democracies to advance democracy internationally through diplomacy, advocacy and information-sharing, including by addressing restrictive laws and regulations that stifle civil society, as well as calling attention to issues such as media freedom and safety of journalists. During Canada’s G7 Presidency in 2018, the G7 Rapid Response Mechanism was announced, with a mandate to strengthen coordination to prevent, thwart and respond to malign and evolving threats to G7 democracies.

“Attacks against human rights defenders are attacks against everyone’s human rights. No one should ever be threatened or face violence for peacefully promoting human rights, or expressing ideas and opinions. We urge Member States to halt attacks on human rights defenders and to provide them with a safe space to carry out their work. In all regions. In all sectors of activities.” Canada’s address to the UN General Assembly High Level Plenary Meeting on the 20th Anniversary of the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, 18 December 2018

2.2 Advancing advocacy through Canada’s bilateral relations

Through bilateral dialogue and its network of missions, Canada engages with local authorities on an ongoing basis to underscore the obligation of states to protect all individuals in their territory and subject to their jurisdiction, including HRDs. Canada may also issue public statements, deliver speeches and use social media or diplomatic démarches in support of HRDs, alone or in partnership with other countries, when such advocacy is not expected to put the safety of HRDs at risk.

2.3 Leveraging partnerships and building capacity, including through funding

Canada regularly seeks opportunities to help build the capacity of civil society organizations, Indigenous peoples, the private sector and local governments, through sharing expertise, experience and technical assistance. This can take many forms, including multi-year funding for key human rights groups, multi-stakeholder engagement to advance awareness of responsible business conduct standards, targeted contributions that Canada’s diplomatic missions offer to grassroots groups for training courses, seminars and other initiatives. Canada also supports human rights education internationally in partnership with Canadian organizations and assists organizations that provide emergency assistance needs. A principal objective is to build bridges between human rights partners and stakeholders.

- Canada has provided $1.75 million since 2016, and will continue to support the work of the Lifeline Project, which helps protect HRDs when they are threatened, as well as $800k in 2017 to the HIVOS Digital Defenders Program, to coordinate emergency support and provide security for bloggers, independent journalists, (cyber) activists, HRDs and other civil society activists.

- Through the Women’s Voice and Leadership Program , announced as part of Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy in June 2017, Canada allocates $150 million over five years to respond to the needs of local women’s organizations working to advance the rights of women and girls in developing countries.

- In May 2018, Canada issued a call to action to civil society, philanthropists and the private sector to collaborate in setting up a new partnership to help address the funding gap faced by women’s organizations and movement with a primary mandate to advance women’s rights, gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in developing countries. Canada is committing up to $300 million to this new funding initiative.

- One of the key objectives of Canada’s 2017-2022 National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security is to increase the meaningful participation of women, women’s organizations and networks, including Indigenous women, in conflict prevention, conflict resolution, and post-conflict state building, which includes supporting the efforts of women HRDs in conflict and post-conflict contexts.

2.4 Promoting responsible business conduct

Canada recognizes the key role played by businesses in protecting and promoting human rights and strengthening the rule of law. Canada has recently released guidance recognizing the key role that the private sector can play to support HRDs: Private Sector Support for Human Rights Defenders: A Primer for Canadian Businesses. This guidance outlines some measures that businesses can take to protect human rights, and to prevent and respond to issues facing HRDs.

Canada adheres to internationally recognized standards and guidelines of responsible business conduct that recall business’ responsibility to respect all human rights, such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights, and encourages Canadian companies to do the same. Canada works with a range of interlocutors to promote responsible business conduct and provides funding to numerous related projects and initiatives in countries around the world.

Canada works with other governments, civil society partners, Indigenous peoples, the private sector, and local stakeholders to enhance capacity to responsibly and sustainably manage natural resources, from an inclusive and human-rights based perspective, which includes respecting the rights and role of HRDs. In particular, Canada works to advance international standards and guidelines to improve performance by all actors involved natural resources management through the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals, and Sustainable Development (IGF), the OECD Responsible Business Conduct Forum, the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights Initiative, and the UN Forum on Business and Human Rights.

Canada’s Trade Commissioner Service also works to inform and support Canadian businesses with respect to their legal obligations under the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act, and promote Canadian industry standards for responsible business such as the Mining Association of Canada’s Towards Sustainable Mining and the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada’s e3 Plus: Framework for Responsible Exploration.

3. Guidelines to support human rights defenders for diplomatic missions

Support for HRDs is a priority issue for Canada’s diplomatic missions. The following section sets out tools and measures that missions can take to support HRDs, including:

- Mapping, information gathering and reporting

- Relationship building, regular contact and information exchange with HRDs

- Enhancing the visibility of HRDs

- Recognizing efforts through awards

- Building capacity and providing funding to HRDs

- Fostering effective HRDs’ support networks

- Engaging with local authorities

- Cooperating with key regional and international actors

- Attending trials and hearings, and visiting detained HRDs

- Making public statements and using social media

- Supporting emergency assistance needs

- Promoting responsible business conduct

A few key principles should be considered at all times.

- Leadership and coherence: Heads of Mission are responsible for the promotion of human rights, inclusion and respect for diversity in their countries of accreditation, including efforts to support HRDs. Officers from different sections of the mission may encounter HRDs in their work, for example in development programming, export control evaluations or consular prison visits. As a best practice, a focal point for HRDs should be designated within the mission to provide leadership and coherence of approaches across different programs. All sections of the mission should share relevant information on HRDs and their political contexts, as appropriate. Missions are also encouraged to provide advice to and seek guidance from specialists at Headquarters (Human Rights and Indigenous Affairs Policy Division, geographic bureau, and other units as appropriate) and from civil society organizations working with HRDs, to ensure their approach to supporting HRDs is considered and effective. When confronted with urgent situations, necessary actions should be taken, drawing on these Guidelines.

- Do no harm: The Guidelines are to be used in a manner that respects the well-being and privacy of HRDs. This applies to decisions about case management, as well as to the sharing of information with partners and with the public. For example, visible support for HRDs and direct contact with foreign authorities may not be the best approach in all instances.

- Consent: HRDs are best placed to evaluate their own situation and recommend what forms of support may be helpful to them, recognizing that situations may evolve, sometimes rapidly. Actions on specific cases should be taken with the free, full and informed consent of the HRD in question, wherever possible, or, that of their representative or families, in the alternative. The HRD or their representative, families or colleagues should also be kept informed of actions taken on their behalf.

- Managed approach: Key elements of a successful approach to supporting HRDs include strategic analysis (including gender-based analysis +), timely action and cooperation with other supporters. A managed approach is typically most effective, with greater emphasis on informal, working-level interventions in the early stages, and increasing emphasis on higher-level, formal interventions as a critical situation evolves. Public interventions, when they are helpful, are most often considered following the pursuit of diplomatic engagement.

- Safety of mission personnel: The safety and security of mission personnel must be borne in mind when considering approaches for supporting HRDs. Risks should be assessed on a case-by-case basis prior to engaging in advocacy, so that they can be weighed against the potential benefit of taking action.

- Intersectionality, specific groups and contexts: HRDs may face particular obstacles because they belong to an identifiable group that faces discrimination in a given country. For example, the challenges and threats faced by women HRDs may be greater and different in nature than those faced by HRDs who are men. Activities mediated through digital technologies also bring with them particular considerations for the protection of HRDs. These differences in groups and contexts must be taken into account when considering an appropriate approach to a given case. Missions should consult the relevant Annexes included in these Guidelines for additional guidance (see section 7).

- Each situation is unique: No single template can be applied when taking action to support HRDs at risk. The Guidelines should therefore be interpreted in the context of local circumstances and conditions on the ground, and in consultation with Headquarters. The various tools for raising awareness, building capacity and intervention should not be considered mutually exclusive and should be used in conjunction with other approaches. They are intended to serve as a checklist to ensure that key steps are considered and that appropriate officials are kept informed in a timely manner.

3.1 Mapping, information gathering and reporting

Canada’s ability to help build capacity and support effective responses to urgent situations depends on the understanding and documentation of evolving contexts and individual cases. A “mapping” exercise can be undertaken to identify human rights organizations and defenders: who they are, whether they are part of a national or international network, and risks they face—with an understanding of the diversity of HRDs and contexts in which they work (missions should refer to the Annexes for guidance on specific groups and contexts).

In assessing the conditions under which HRDs work, missions should consider: if issues and risks are emblematic of particular practices (e.g. restrictions on the exercise of freedom of expression or peaceful assembly—in law or in practice); systemic causes and new and emerging threats; the volume of alleged and reported threats and attacks; whether authorities make any efforts to protect HRDs and to investigate attacks against them (level of impunity); and whether there is a dialogue between the authorities, civil society and HRDs. Missions should also identify which other actors are working on the issue of HRDs—including other diplomatic missions, regional and international actors, national institutions and human rights commissions, academics, media and the private sector. In addition, missions will consider links to Canada’s development priorities and programming contexts, trade program contexts such as the intersection of business and human rights, and the identification of Canadian entity involvement in alleged or apparent human rights violations or abuses.

Examples of incidents posing risks to HRDs

- New legislation is passed that restricts or curtails fundamental rights or freedoms.

- A HRD experiences specific threats, intimidation or violence.

- Activist reported detained without charge, or on questionable charges.

- Witness or lawyer disappears following testimony or legal proceedings against authorities.

- Civil society, media organization or Indigenous community critical of government’s record on human rights is banned or faces legal sanctions.

- Demonstration or other public event occurs where HRDs are likely to be at risk.

Missions are encouraged to monitor relevant situations and report regularly on developments in their countries of accreditation. Information should be shared between personnel at Canada’s diplomatic missions and those at Headquarters—in particular with the relevant geographic bureau at Headquarters, copying the Human Rights and Indigenous Affairs Policy Division and other units as appropriate. Missions reporting should refer to the reporting checklist below in cases of HRDs at risk.

Reporting checklist in case of HRDs at risk

- Basic background on a case: individual (named only if safe and appropriate), network/organization/community affiliation, group, context and type of activities

- Local conditions/legislation with respect to HRDs, and the issues on which defenders are engaging

- Particular incident, alleged perpetrator, and how it constitutes a human rights violation or abuse

- Assessment of the level of personal security of the HRD, their families and communities

- Reactions from authorities, civil society and other stakeholders (diplomatic and public)

- Specific request for support from HRD (if any) and proposed mission intervention (where relevant), outlining the risks associated with the recommended approach and how these will be mitigated

- Outcome/result of Canadian intervention(s) (when relevant), including reactions from government authorities, civil society, affected communities and the media, and any threats or reprisals against HRDs

- Regular updates with changing circumstances as appropriate

Information should be maintained in a manner that respects confidentiality, so it neither adds to the risks faced by HRDs nor diminishes Canada’s ability to provide support. The management of this documentation brings with it serious considerations with respect to the protection and safety of HRDs. Officials can ensure protection of sources and security of information by applying standard operational safeguards, including the use of appropriate level of classification when referring to individuals (see Appendix A). Documentation made or shared through digital technologies must take digital security into consideration to ensure the safety of HRDs connected to the creation, transmission or receipt of these documents (see the Annex on HRDs in Online and Digital Contexts).

3.2 Relationship building, regular contact, and information exchange with human rights defenders

Missions should seek to build and maintain relationships with HRDs and civil society organizations—from well-funded organizations to marginalized grassroots movements, in urban and remote areas. Contact with HRDs can help missions better understand their situation and the local context in which they work, and facilitate response should an emergency situation arise.

Wherever possible, it is important to maintain regular contact with HRDs, or their representatives or families, to keep up-to-date on their circumstances and preferences for any assistance they seek. Direct contact is encouraged, but is not a prerequisite for Canada to provide support. Often, a single diplomatic mission or civil society organization in the country where a HRD works serves as the point of contact between the HRD and the organizations and individuals working together to support their efforts to promote respect for human rights. Online or digital communications can be a useful tool in this regard, but appropriate safety considerations associated with this mode of communication and information sharing is paramount (see the Annex on HRDs in Online and Digital Contexts).

3.3 Enhancing visibility for human rights defenders

Giving greater visibility to HRDs often contributes to their safety by demonstrating that “the world is watching,” therefore dissuading authorities from taking actions against them. Public recognition also lends credibility to HRDs and credibility to their work, which is particularly important for those who may the subject of campaigns to discredit them.

To demonstrate the importance of the work of the defenders, missions can, for example, conduct field visits, either independently or accompanied by other diplomatic missions, to meet with HRDs in the variety of settings where they conduct their advocacy. Such visits can sometimes take place in remote regions, often within sight of local authorities and security forces. They are generally most strategic and useful when they are rooted in local contexts and coordinate with local groups and networks. HRDs can also be invited to mission functions as honoured guests, together with host authorities, the private sector, and others with influence on government actions. Visibility can also be enhanced through public communication and social media.

As with any action on specific cases, consultation with the HRD, their representative or families prior to any profile-raising activity is essential. Association with foreign diplomats can sometimes create new risks for them, their families and their communities.

3.4 Recognizing efforts through awards

Canadian missions are encouraged to present or support awards that recognize the achievements of HRDs for championing specific human rights issues. Awards can serve to honour individuals or groups that show leadership in defending human rights and freedoms at the local, regional or international level.

“I was motivated to become a defender of human rights due to the situation of vulnerability that I had been witnessing and documenting, and what inspired me to continue was the resilience I saw in families, and in the children themselves. While we are currently living through very difficult times, I am filled with hope for a better Venezuela, one in which we are all human rights defenders.” Katherine Martínez, Recipient of the 10th edition of the Embassy of Canada Human Rights Award

As part of the award, over the course of the year the winner will travel to Canada, and across Venezuela, where various meetings will be organized with universities, human rights organizations and government authorities, to share experiences in the defence of human rights.

3.5 Building capacity and providing funding to human rights defenders

Where possible, missions are encouraged to use funds available to support human rights organizations, HRDs and their communities, including through the Post Initiative Fund (PIF) or the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI). Funding can help support the work of HRDs, strengthen capacity, and build connections with HRDs networks. For example, funds can be used to develop and deliver training and knowledge-sharing projects aimed at building capacity for HRDs and strengthening their networks.

Through the CFLI, Canada provided over $570,000 to 27 projects supporting HRDs in 16 countries in 2017 and 2018. Projects included workshops to build the capacity of HRDs to report on human rights violations; safety and security training seminars for HRDs; and activities to support networking between HRDs.

3.6 Fostering effective human rights defenders’ support networks

Canadian representatives abroad are expected to maintain networks of contacts among groups and individuals advocating on behalf of the protection and promotion of human rights. Canadian missions can play an important role in fostering the development of effective support networks that can include diplomatic missions, government authorities, journalists, academics, the private sector (including Canadian companies in market) and other stakeholders. These networks provide essential resources to support HRDs at risk, including vital information, advice and access to sources of influence. They may also provide added credibility in dealing with local authorities, the public and HRDs themselves.

3.7 Engaging with local authorities

Canadian representatives should build and maintain relationships with influential local authorities or those authorized to make decisions affecting human rights. These may include, for example, host government ministers and their staffs, national human rights institutions, ombudspersons, partisan or public service officials, legislators, and regional and municipal leaders.

Canadian missions should maintain both formal and informal channels to discuss human rights issues with local authorities on an ongoing basis. Established mechanisms and relationships built on trust can create opportunities for collaboration and can facilitate the resolution of difficult issues.

In cases where HRDs are at acute risk, it is often fruitful to engage local authorities discreetly through such established networks and mechanisms. In many cases, informal outreach can help to resolve emerging crises in their early stages. Approaches can be made at senior levels as necessary, for example as part of meetings between ministers and the Head of Mission. Similarly, formal diplomatic mechanisms can be engaged when informal mechanisms have been exhausted or are inappropriate. Formal approaches can include, for example, diplomatic notes or démarches, and can be coordinated with other diplomatic missions. In some cases, firmer diplomatic measures may be required. These could include, for example, Headquarters calling in a foreign diplomat to discuss the case or, rarely and exceptionally, recalling a Canadian diplomat to mark strong disapproval of the actions of the host government.

3.8 Cooperating with key regional and international actors

Cooperation with and support for regional and international bodies and mechanisms is another recognized avenue for supporting and enabling strong institutions to promote and protect human rights.

Within the UN system, the OHCHR supports respect for human rights at the national level through its network of regional offices and hubs, or as part of UN missions, with additional focus on cross-cutting regional human rights concerns. UN special rapporteurs and independent experts regularly undertake country visits. Missions should cooperate with the special rapporteurs or independent experts visiting the host country as appropriate, for example by inviting them to participate in round-table talks or to discuss the situation of HRDs with stakeholders from local civil society and representatives of Indigenous communities. As noted in Section 2.4, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders is specifically mandated to gather information on the situation of HRDs around the world. Other relevant interlocutors include the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, the Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples, the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary and arbitrary executions, the Independent Expert on sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights. Reporting from those special rapporteurs and independent experts, in particular on country situations, can provide valuable information for missions.

Beyond the close cooperation between missions in a region on cross-cutting themes and issues, Canadian missions should continue to work within regional institutions to promote and protect human rights and to support HRDs.

Regional mechanisms:

- Africa: African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights – Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders

- Americas: Organization of American States – Rapporteurship on human rights defenders

- Asia: ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights

- Europe: Council of Europe – Commissioner for Human Rights

- Middle East: Araba League – Arab Commission on Human Rights

- OSCE – Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights

3.9 Attending trials and hearings, and visiting detained human rights defenders

Attendance by Canadian officials at trials or hearings involving HRDs—a clear and visible expression of Canada’s concern—can be helpful by allowing for detailed tracking of legal proceedings, observing whether due process is respected, and ensuring up-to-date information on cases of particular interest, taking into account the impacts of gender discrimination within the justice system. Canada’s involvement often presents networking opportunities with human rights organizations, other diplomats and local authorities. When several diplomatic missions follow a case, or when a trial is held in a remote or difficult-to-access area, it can be helpful to establish a roster to share trial-attendance duties and information on trial-related developments.

Seeking to visit HRDs detained by local authorities in custody or under house arrest as a result of their human rights advocacy work can, in some instances, be a helpful means of showing support. This is an instance when the well-being of the individual, and the potential impact on the mission, must be weighed with particular care, and when the mission should consult Headquarters before taking action.

Local authorities do not always allow foreign diplomats to attend trials and restrictions on visiting HRDs in detention are very common. In such cases, requesting permission to attend can nevertheless demonstrate to local authorities that there is continued international interest in the case.

3.10 Making public statements and using social media

Missions are encouraged to use positive communications recognizing the role and legitimacy of HRDs, which can help counter the negative propaganda carried out in some countries seeking to delegitimize their role.

While diplomatic engagement is in most cases the primary approach for Canada, public interventions can be an effective tool to support HRDs who are at risk or have been detained. They can bolster efforts by local and international actors to pressure a government to take positive steps. Public interventions can include open letters, op-eds, news releases, news conferences and social media postings published by mission or Headquarters accounts. Although they may be made unilaterally by Canada, interventions typically have greater impact when made in coordination with other concerned countries. Interventions should reach local authorities, media, and key actors of influence, as well as those who appear to be directly and indirectly responsible for the attacks on HRDs.

Public interventions are most effective when the government in question is called upon to meet its own international human rights obligations. Interventions can refer to the Core International Human Rights Instruments ratified by the State, and to observations and recommendations issued by the committees (treaty bodies) set up under these instruments to monitor the implementation by the state of its human rights obligations (see Section 2.4). Canadian interventions can also make reference to Articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders (see Section 2.4), or to actions on human rights that are recommended to states through the Universal Periodic Review (see Section 3.1).

Common public appeals include urging authorities to conduct prompt and impartial investigations of alleged violations of human rights and to take all necessary measures to ensure the protection of all people against violence, threats, retaliation, discrimination, pressure or any other arbitrary action as a consequence of the legitimate exercise of their rights.

Drawing publicity to a case can sometimes make diplomatic efforts more difficult. The HRD in question, or their representative or families, should be consulted wherever possible, as public statements by foreign governments can lead to reprisals against the defenders, their families, their communities, or other HRDs. Special care needs to be taken whenever missions are unable to make contact, and must take into account the best interests of the individual. Headquarters should be consulted before a decision to undertake a public intervention is made on a given case.

3.11 Supporting emergency assistance needs

HRDs may face acute threat, such as serious risks of death or injury. In response to requests for assistance from HRDs in emergency situations, missions should use the checklist provided in Section 4.1 and the information provided in the Annexes to better assess the situation and identify appropriate measures to support them. Missions should also report to Headquarters (relevant geographic bureau, Human Rights and Indigenous Affairs Policy Division and other units as appropriate), ensuring confidentiality of information. Collaboration with like-minded diplomatic missions is highly encouraged, recognizing that missions may be able to offer varying forms of assistance and as such may complement each other in providing support to defenders (a list of existing guidelines for diplomatic missions is provided in Appendix B). Missions should also collaborate with local and regional networks of HRDs, many of whom have developed their own strategies to respond quickly and effectively to the specific needs of HRDs in crisis situations. As it is the case with other interventions, missions should ensure that the human rights defender in question is kept informed of action taken on their behalf, results, and any follow-ups.

HRDs at risk will often want to pursue their human rights activities while finding a safe environment in their home country, or alternatively in a neighbouring country. Missions can provide practical assistance for temporary relocation, within the limits of the law and resources available.

A number of civil society organizations specialize in providing emergency assistance to HRDs. Assistance provided by these organizations can include legal support, temporary shelter, and funding to cover living costs and personal protection. Some organizations can also offer assistance in situations where a HRD feels it is necessary to leave their home country temporarily to continue their work. Missions are encouraged to refer HRDs at risk to these organizations—understanding that the organizations may have expertise but limited capacity.

Example of organizations providing emergency assistance to Human Rights Defenders

- Lifeline provides small, short-term emergency grants to civil society organizations threatened because of their human rights work. These grants can help with the costs of security, medical expenses, legal representation, prison visits, trial monitoring, temporary relocation, equipment replacement and other urgencies. Canada provides financial support to Lifeline.

- Front Line Defenders provides Protection Grants to HRDs to improve physical and digital security, for legal and medical fees, and to assist the families of imprisoned HRDs. The organization also provides emergency assistance to HRDs, including help with temporary relocation. It provides 24-hour phone assistance in Arabic, English, French, Russian and Spanish: +353-1-210-0489.

- Urgent Action Fund provides rapid response grants in response to security threats experienced by women, transgender, or gender non-conforming activists and HRDs.

- The Dignity for All: LGBTI Assistance Program provides emergency assistance, security, opportunity, and advocacy rapid response grants, as well as security assessment and training, to HRDs and civil society organizations under threat or attack due to their work for LGBTI human rights.

- International Cities of Refuge Network provides shelter to writers and artists at risk, advancing freedom of expression, defending democratic values and promoting international solidarity.

Additional organizations are listed in the Annexes to these Guidelines.

HRDs seeking shelter abroad will often do so in a neighbouring country, close to their families and local networks. Missions should refer individuals who move to another country and wish to make asylum claims to the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which is mandated to assist with emergency evacuation and long-term protection. If a referral by the UNHCR is made to Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) can assess the case under its Urgent Protection Program (see Section 5.3). Permanent relocation is often the last resort for HRDs.

3.12 Promoting responsible business conduct

HRDs may face risks and attacks directly or indirectly related to private sector activities. This is particularly true for HRDs working on corporate accountability issues, including women and Indigenous HRDs, as well as land and environmental rights defenders (see Annexes).

To ensure a safe environment for HRDs, Canadian missions are encouraged to actively promote awareness and understanding of responsible business conduct guidelines such as the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights, and the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights among host governments, Canadian and local private sector, and civil society actors, using available tools for public diplomacy and trade promotion. The Voluntary Principles can help to guide a company in training practices regarding proportional use of force, due diligence in the selection of security forces, and working collaboratively with civil society organizations and government to prevent human rights abuses from occurring.

Using its convening power, missions can organize, sponsor or participate in public events where Canada can promote responsible business conduct practices, including for meaningful engagement with HRDs and stakeholders, where appropriate. Missions are encouraged to create opportunities for such exchanges through conferences, workshops and other activities involving companies, representatives of host governments, and civil society. Missions should be aware that such activities may not always be appropriate, as it may put HRDs at risk. As is the case with other measures, missions should ensure no harm is done.

4. Specific cases with a Canadian nexus

4.1 Canadian human rights defenders

When a HRD at risk is a Canadian citizen—regardless of whether they also have citizenship in the country in question—must be considered a consular case. Such cases involve specific diplomatic agreements that govern consular affairs and specific mechanisms to be used at Global Affairs Canada for engagement. Missions must promptly report these cases to consular officials at Headquarters and to the appropriate geographic branch.

When the individual is not a Canadian citizen but has other ties to Canada, such as permanent residency, missions should report the case to the appropriate geographic branch.

4.2 Canadian corporate entities

HRDs—including those advocating for rights related to land and the environment—often focus on the activities of multinational corporations, subsidiary companies and contracted organizations in supply chains. Support for these HRDs should be provided as outlined in the Guidelines, regardless of the nationality of the company in question. Missions are expected to provide support to HRDs even when they allege or appear to have suffered human rights abuses by a Canadian company that receives support from Canada’s Trade Commissioner Service. Coherence of approaches across different programs is particularly important in such cases.

Canadian companies working internationally are expected to respect human rights and to operate lawfully, transparently and in consultation with host governments, Indigenous and local communities, and to conduct their activities in a socially and environmentally responsible manner. Preventive measures are important to ensure a safe environment for HRDs. In instances where Canadian businesses are allegedly or appear to be involved in a case of human rights abuse against HRDs, the mission must refer to Canada’s Enhanced Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Strategy to Strengthen Canada’s Extractive Sector Abroad in addition to providing support and protection to the HRDs in question, as appropriate. Although focused on the Canadian extractive sector abroad, the Strategy provides broad guidance on responsible business conduct policy and practice applicable to all sectors. Missions should also seek direction from the Responsible Business Practices Division, the Human Rights and Indigenous Affairs Policy Division, the applicable geographic bureau and other relevant units at Headquarters, and must ensure close collaboration between the sections of the mission responsible for international business development and bilateral diplomatic relations. Depending on the facts of a given case, there may be an impact on the support that the mission offers to the Canadian company in question, including denying or withdrawing individualized trade advocacy support.

In cases involving conflict between an affected community and a Canadian company, its subsidiary, sub-contractors and/or suppliers, one of Canada’s dispute resolution mechanisms could be called upon to review instances and make non-binding recommendations: Canada’s National Contact Point for the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises or the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise.

The Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise is mandated to review allegations of human rights abuses arising from Canadian company operations abroad in the mining, oil and gas, and garment sectors, as well as to provide recommendations to help resolve disputes.

The Ombudsperson is mandated to promote the implementation of internationally endorsed human rights guidelines and advise Canadian companies operating in the mining, oil and gas, and garment sectors on best practices. The missions can play an important role in connecting the Ombudsperson with Canadian companies on the ground, host-country national human rights institutions, local communities and civil society organisations representing HRDs and other vulnerable groups advocating for their rights

Missions should refer to Section 3.4 for additional information on Canada’s approach to supporting responsible business practices, as well as Section 4.12, which includes specific guidance for missions, and the whole set of measures outlined in Section 4 and the Annexes.

4.3 Seeking asylum in Canada

A HRD seeking to urgently leave his or her home country temporarily will typically seek refuge in a nearby country. However, in cases where a HRD requests temporary refuge in Canada, but does not hold a valid Temporary Resident Visa (visitor visa) and is not a Canadian citizen or Permanent Resident, officials should consult with the mission’s visa section or contact Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). HRDs seeking refugee status in Canada should be advised to register with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) whose mandate includes identifying what measures, including protection and possible resettlement, might be required. Once the UNHCR becomes involved, IRCC can assess the case under its Urgent Protection Program.

5. Implementation

Global Affairs Canada is committed to implementing the Guidelines at Headquarters and at missions. The Guidelines reflect Canada’s clear commitment to supporting the vital work of HRDs.

The Guidelines will be made available on Global Affairs Canada website and distributed electronically to human rights organizations and other stakeholders.

Officials at Headquarters and at missions are encouraged to increase awareness of the Guidelines, for example by referring to them in meetings at political level, in human rights dialogues and consultations, at multilateral and public forums, on official visits, and in public communications, including on social media. In particular, missions are encouraged to promote the Guidelines at the local level to ensure awareness among HRDs, human rights organizations and other stakeholders—including those from rural areas and marginalized groups. Organizing events at the mission and conducting visits to remote areas to disseminate the Guidelines is encouraged.

Missions should do their utmost to implement the Guidelines, recognizing that each approach should be tailored to local contexts and circumstances, and respond to the specific needs of HRDs. Canadian missions are best placed to balance the objectives of the Government of Canada, identify risks to HRDs and opportunities to support them, leverage contact networks, and communicate the impact on the ground. Missions should regularly review the role of human rights in all aspects of the bilateral relationship and take steps to lay the groundwork for increased engagement. Long-term approaches are encouraged and should include taking full advantage of opportunities to build local capacity, including through the Post Initiative Fund (PIF), the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI) and development assistance, and to build bridges between human rights partners and stakeholders. Missions are encouraged to use the Guidelines in developing local implementation strategies, including through annual mission planning. Relevant Headquarters divisions will assist with mission initiatives.

In line with the head of missions’ performance management commitment to broaden Canadian efforts on human rights, it is expected that human rights issues will figure regularly and prominently in political and economic, development and trade initiatives and that engagement undertaken by all missions will be reported as developments unfold. As part of this, missions should include details on the situation of HRDs in periodic and ad hoc human rights reporting. As noted above (Section 4), missions should identify a focal point responsible for implementing the Guidelines and for providing leadership and coherence of approach across different programs.

The use of these Guidelines by officials at missions and at Headquarters is supported through training prepared by Global Affairs Canada through the Office of Human Rights, Freedoms and Inclusion. Training on the Guidelines are offered through human rights courses, corporate social responsibility training, and consular training in collaboration with relevant trade, development and consular divisions. Officials from all streams at missions are encouraged to follow the trainings as part of their pre-posting preparation, or while on posting. An online component is also available. Missions are encouraged to turn to the Office of Human Rights, Freedoms and Inclusion for ongoing guidance, as needed.

The Guidelines are an evolving document. Officials at missions will be called upon to assist in the periodic revision and improvement of the Guidelines to reflect changing circumstances with respect to situations faced by HRDs in the field and evolving international norms.

The Government of Canada has consulted with representatives of civil society in developing these Guidelines. Ongoing engagement with these dedicated experts has been and will remain invaluable in strengthening the Guidelines.

Canada will continue to be a strong advocate for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and respect for diversity and inclusion. An important part of these efforts is Canada’s recognition of and support for HRDs—wherever they are and however we can.

6. Annexes

HRDs often have multiple and intersecting identities and experiences. The challenges and threats they face, and the support they need, may vary accordingly, because they belong to one or more specific identifiable groups that face discrimination and/or because of the context in which they work. The following annexes seek to recognize the specificities of experiences lived by HRDs belonging to one or more groups, in various contexts, including: women HRDs, LGBTI HRDs, Indigenous HRDs, land rights and environmental human rights defenders, disability rights defenders, youth HRDs, freedom of religion or belief HRDs, journalists, and HRDs in online and digital contexts. The annexes identify the main risks and challenges faced, best practices and resources for missions.

The groups and contexts outlined in these annexes are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive, nor hierarchical. The annexes should be read in conjunction and complementarity to one another, and to the guidance provided in the core document (in particular in Section 4 of the Guidelines). Multiple annexes may apply to each HRD. The multiple and intersecting identities of a HRD must be taken into account when considering an appropriate approach to a given case, bearing in mind that some of a HRD’s many identities may be invisible to others.

6.1 Women human rights defenders

Definition

Women HRDs are generally women engaged in the promotion and protection of human rights. The group can also include persons of all genders working on women’s rights and gender issues.

Women’s HRDs often use local, regional and international networks, and work collaboratively and holistically to resolve crises.

Risks and challenges faced

Women HRDs may be targeted for or exposed to gender-specific threats and violence, including in online and digital contexts, for example through social media, Internet and ICT platforms. They are at higher risk than men of sexual and gender-based violence, online attacks, cyberstalking, sexual harassment and intimidation.

The human rights work of women HRDs often challenges traditional norms of family and gender roles in society. As a result, the defenders may be subjected to gender and sexual stereotypes, stigmatization or ostracism by community leaders, faith-based groups, families and communities who perceive their work as threatening religion, honour or culture that runs contrary to the laws and customs of society. For example, women HRDs standing for sexual and reproductive health and rights, working on sexual orientation and gender identity rights, environmental, land or labour rights face greater risk of intimidation, harassment and violence by state or non-state actors, local authorities, anti-government elements, and private sector entities, according to the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders World Report (2018). Moreover, sexual violence, defamation and intimidation, including against their family members, are being used as deterrence. In 2017, Front Line Defenders recorded that 44 women HRDs were killed; an increase from 40 in 2016 and 30 in 2015.

Women HRDs in conflict and post-conflict situations face multiple and intersecting forms of violence, distrust and prosecution, due in part to the multifaceted nature of conflict, displacement and migration status, which often involves several parties whose accountabilities can be difficult to determine. In militarized contexts and countries in conflict, women HRDs may face additional threats of sexual and gender-based violence and incarceration, and their children and family members are more likely to be threatened or attacked as a form of intimidation. In general, women HRDs must consider the well-being of their families, as many are also the main or sole caregivers.

Best practices

Missions should address the situation of women HRDs in their reporting, noting in particular the occurrence of any threats or attacks against them and their ability to undertake their work in safety, as well as practices that are potentially harmful and areas where they can be supported to mitigate risks.

Missions can play a significant role to protect and support the work of women HRDs, for example through:

- Engaging actively with women HRDs, women’s rights organizations, women’s rights movements, and public and private sector actors, where appropriate;

- Monitoring, documenting and reporting human rights violations, the gendered consequences of such violations, and state and non-state perpetrators who pose specific threats;

- Supporting investigative processes into alleged acts of intimidation, threats, violence and other abuses against women HRDs;

- Identifying the specific needs of women HRDs and responsive actions, for example protection measures, relocation plans, psychosocial support, childcare or other support services and resources;

- Working at local, national and regional levels to coordinate efforts and response mechanisms to ensure the protection and safety of women HRDs, leveraging women’s rights organizations networks.

Missions can also play a role in promoting the meaningful participation of women in policy and development processes, peacebuilding and post-conflict governance processes that promote gender equality. Examples include:

- Recognizing all women HRDs as legitimate human rights actors, increasing visibility and lending credibility to their activism;

- Amplifying public campaigns that recognize the work of women HRDs as an important public policy measure to address structural violence;

- Building public demonstrations of support and recognition in society from local authorities, within communities and the families of women HRDs;

- Working with partners and creating safe and inclusive spaces for the involvement of women HRDs in decision-making and negotiation processes, community agreements and in human rights due diligence processes; and

- Taking extra efforts to include women from crisis-affected populations to participate in humanitarian assistance, protection and recovery programs.

Resources

- Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development

- AWID

- Canada’s National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security

- Initiativa Mesoamericana de Mujeres Defensoras de Derechos Humanos

- International Service for Human Rights

- MATCH International Women’s Fund

- Nobel Women’s Initiative

- Women Human Rights Defenders International Coalition

6.2 LGBTI human rights defenders

Definition

LGBTI HRDs are people who act to promote or protect the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) persons.

LGBTI HRDs are typically members of the LGBTI community, but they do not necessarily belong to this community. They are advocates for the rights of LGBTI persons regardless of their own personal sexual orientation, gender identity or sex characteristics.

Risks and challenges faced

LGBTI HRDs are regularly subjected to harassment and intimidation, arrest, physical attack, negative portrayal in news media and social media, and interference with their lawful exercise of rights, such as freedom of expression and freedom of assembly. Some are killed for engaging in their work. LGBTI HRDs may also experience extreme isolation and a lack of political or social support from others, including other HRDs.

It should be borne in mind that the term LGBTI encompasses multiple distinct communities and that LGBTI HRDs may experience unique challenges depending on the particular community whose rights they seek to protect. For example, the circumstances and needs of transgender HRDs may differ in important respects to those of gay and lesbian HRDs. There is also a need for sensitivity to gender dynamics: in particular, women HRDs—whether lesbian, bisexual or transsexual women—may face additional challenges and risks in carrying out their work as compared to men.

A number of factors account for the range of challenges and risks facing LGBTI HRDs. A key factor is the persistence of negative social attitudes regarding LGBTI persons. In many countries, an absence of legislation prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity or sex characteristics contributes to the continued social marginalization of LGBTI persons. Negative attitudes towards LGBTI communities may also be reinforced by the public influence of certain religious groups or leaders that characterize LGBTI persons as being unnatural or immoral. In some countries, acceptance of LGBTI “lifestyles” is considered to be a Western concept that is contrary to the beliefs and wishes of the local population, and this perception leads to increased hostility towards LGBTI HRDs.

Criminalization of same-sex conduct is a further significant obstacle for LGBTI HRDs in many parts of the world. Same-sex conduct remains a criminal offence in nearly 70 countries, and is punishable by death in at least five countries. LGBTI HRDs working in countries where same-sex activity is illegal are at particular risk of having their work suppressed by state authorities, since they are perceived to condone criminal behaviour.

Security officials and judges often lack training on the particular circumstances and needs of LGBTI HRDs, making it more difficult for these defenders to seek assistance or obtain justice when they are attacked or threatened.

Best practices

Mission staff should acquire a thorough understanding of the local context relevant to the work of LGBTI HRDs, including knowledge of national laws and policies for protecting the rights of LGBTI persons, as well as awareness of societal attitudes towards LGBTI communities.

In addition to fostering relationships with local LGBTI civil society organizations, missions should seek to identify and foster links with local allies of LGBTI HRDs. It will be helpful to think broadly about where potential allies may exist—for example, there may be important supporters within the business community and among religious leaders.

Given the vulnerability of LGBTI HRDs in many parts of the world, missions should pay attention to the threats to safety and security that they may face even as they attempt to reach out to missions for assistance. Depending on the context, consideration should be given to whether specific measures are needed to facilitate safe interactions between LGBTI HRDs and mission staff.

Missions should collaborate with like-minded missions in responding to requests for assistance from LGBTI HRDs, recognizing that missions may be able to offer varying forms of assistance and as such may complement each other in providing support to defenders.

In general, the exercise of good judgment and discretion by mission staff is crucial for determining the ways in which missions can best provide support to LGBTI HRDs, while also avoiding exacerbating the risk of harm to the defenders and to local LGBTI communities. To ensure that appropriate decisions are made, it is important that mission staff remain attentive to the views of LGBTI HRDs regarding the types of mission support they do and do not wish to receive in a given situation.

Resources

Organizations:

- ARC International

- Dignity Network

- Equitas

- Freedom House (Dignity Consortium)

- Global Equality Fund (U.S. Department of State)

- ILGA World (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association)

- International Service for Human Rights

- OutRight Action International

- Rainbow Railroad

Useful documents:

- Situation of Human Rights Defenders (Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders, July 2015)

- State Sponsored Homophobia Report (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association)

- Strengthening Protection for Human Rights Defenders (ARC International)

6.3 Indigenous human rights defenders

Definition

Indigenous HRDs are Indigenous individuals, groups and organizations working to assert and defend human rights, including the rights of Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous peoples’ rights have been increasingly recognized through the adoption of international instruments and mechanisms, including the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Risks and challenges faced

Indigenous peoples, who make up five percent of the world population, overwhelmingly face major challenges to enjoying their basic rights. According to indicators, they are among the most disadvantaged and marginalized of the world’s groups, and face persistent vulnerability and exclusion.

Human rights violations and abuses are committed against Indigenous HRDs worldwide. Although some countries have taken constitutional and legislative measures to recognize the rights and identities of Indigenous peoples, Indigenous peoples are often discriminated against and do not receive protection under the law. Indigenous HRDs are more readily criminalized for claiming title to traditional territories and are subject to charges such as illegal occupation.