“Tell them we’re human” What Canada and the world can do about the Rohingya crisis

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

As Prime Minister Trudeau’s Special Envoy to Myanmar, I engaged in extensive research, travel and meetings with key interlocutors from October 2017 to March 2018 to assess the violent events of August 2017 and afterward that led more than 671,000 Rohingya to flee their homes in Rakhine State, Myanmar, and seek refuge in neighbouring Bangladesh.

This report focuses on the following four themes: the need to combine principle and pragmatism in responding to the serious humanitarian crisis in both Myanmar and Bangladesh; the ongoing political challenges in Myanmar; the strong signals that crimes against humanity were committed in the forcible and violent displacement of more than 671,000 Rohingya from Rakhine State in Myanmar; and the clear need for more effective coordination of both domestic and international efforts.

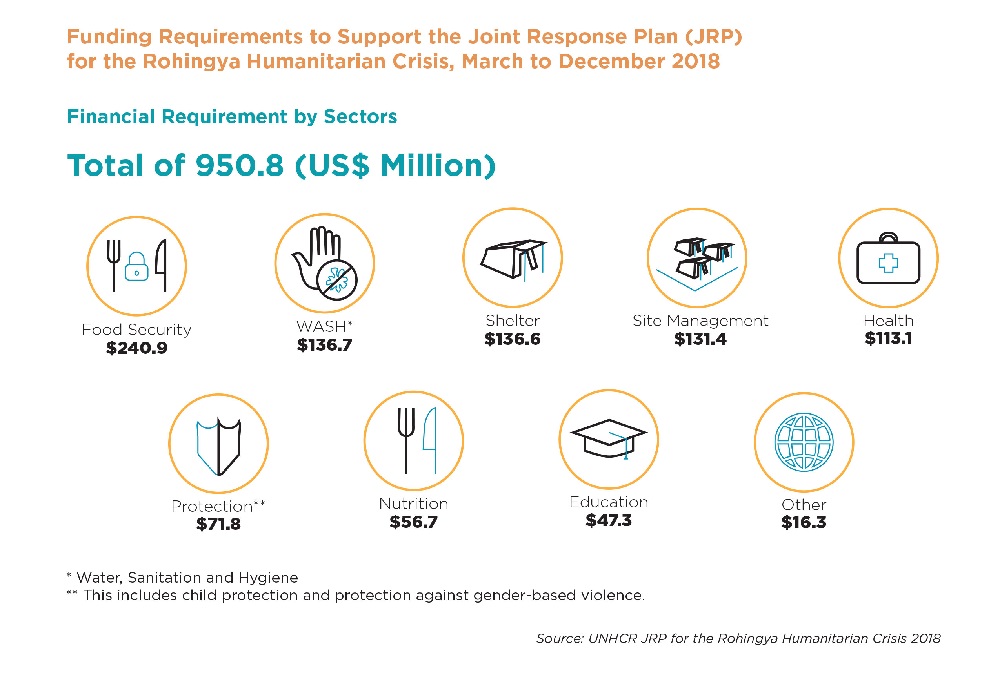

The humanitarian crisis in Bangladesh and Myanmar: With the arrival of more than 671,000 additional refugees in Bangladesh since August 25, 2017, the displaced Rohingya population living in camps in Bangladesh now approaches one million. Camps are overcrowded, the population is traumatized, and the rainy season will soon be upon them. UN agencies have responded with a Joint Response Plan aiming to gather US$950.8 million for the next year. In addition, there could be as many as 450,000 Rohingya remaining in central and northern Rakhine State. Their situation is precarious. Many are in camps for internally displaced persons (IDP), and others are essentially locked into their villages, with poor food supplies and little access to international humanitarian assistance. This demands a response from the international community, and Canada needs to play a strong role. Canada needs to increase its budget dedicated to the crisis, as well as to encourage deeper coordination with like-minded countries. Canada and other countries should also explore avenues to allow the Rohingya to be eligible to apply for refugee status and resettlement, including in Canada, but it needs to be stressed that resettlement alone will not solve the problem.

The political situation in Myanmar: The military remains in firm control of key ministries and budgets within the government that is currently in place in Myanmar. In addition to the crisis in Rakhine State, military conflict is taking place in many border areas of the country, having a negative impact on the peace negotiations and constitutional reform as a result. Despite the 2015 democratic election of Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD), she was not permitted by the constitution to become president and instead has the role of Minister of Foreign Affairs and State Counsellor, an office that was created for her and whose responsibilities are not clearly defined. She remains the main interlocutor of Myanmar with the world and has been defensive of the activities of the Myanmar military in Rakhine State. The Government of Myanmar, at least its civilian wing, is now formally committed to the implementation of the recommendations of the Kofi Annan-chaired Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, which seek to bring long-term peace and stability to Rakhine, but howthese recommendations can in fact be implemented is not yet clear. The government has also said it will allow for the return of the Rohingya to their home villages, but evidence suggests that many of these villages have been destroyed, and there is a prevailing sentiment within the local ethnic Rakhine population against the Rohingya’s return. Consequently, United Nations (UN) agencies have stated that they do not believe conditions are present for the “safe, voluntary, dignified, and sustainable” return of the Rohingya to their homes in Rakhine State. I agree with this view. Canada needs to continue to engage with the Government of Myanmar, in both its civilian and military wings, and continue to do so in a way that expresses candidly its views about what has happened, and is still happening, and to insist that all activities of the Government of Myanmar, including military activities, must be carried out in conformity with international law. Canada also needs to engage with civil society throughout Myanmar to support the peace process and to insist on the need for international humanitarian access to northern Rakhine.

The question of accountability and impunity: There is clear evidence to support the charge that crimes against humanity have been committed. These have led to the departure, often in violent circumstances, of more than 671,000 Rohingya from Rakhine State since August 2017. This evidence has to be collected, and we need to find a way to move forward to bring those responsible for these crimes to justice. It will not be easy, as Myanmar is not a signatory to the Rome Statute, but steps should be taken to encourage the International Criminal Court to consider an investigation on the issue of forcible deportation. In addition, Canada should lead a discussion on the need to establish an international impartial and independent mechanism (IIIM or “Triple I-M”) for potential crimes in Myanmar, such as was established by the UN General Assembly for Syria. The Government of Canada should be actively involved in funding these efforts and in continuing to apply targeted sanctions against those where credible evidence supports such measures.

Effective coordination and cooperation: The report recommends formalizing the coordinated efforts of the Rohingya Working Group within the federal government to include those departments with a clear interest and mandate (Global Affairs Canada, Justice Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, the Department of National Defence, PCO, PMO) and continuing discussions with other like-minded governments about coordinating international efforts on the three challenges described above.

Introduction

Canada’s Prime Minister Trudeau and Special Envoy Rae discussing the Rohingya crisis / Image source: Government of Canada

I accepted Prime Minister Trudeau’s invitation to serve as Canada’s Special Envoy to Myanmar on October 23, 2017. Since that time, I have visited the region twice—the first time in November 2017 and the second in February 2018—and have been in touch with a large number of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), advocacy groups, UN and other international agencies, and many government officials. I have been ably assisted by officials in Global Affairs Canada and have been accompanied on many of my travels by Maxime Lauzon-Lacroix, Senior Desk Officer at Global Affairs Canada. I am extremely grateful to him and many others for their guidance and advice. I have, of course, discussed the report with many people over the last several months, but this report, its conclusions and the recommendations are mine. It is a personal reflection, and in that sense represents a difficult journey. I have found myself dealing with a deeply intractable and, in many ways, tragic situation. It lends itself to moral outrage, anger and frustration. But as I have learned over many years, these emotions are not necessarily the best guide to action.

I hope that those reading this document, including officials and politicians in Myanmar and Bangladesh, will understand that while I have spent much time reading and discussing the current situation facing the Rohingya people, I am by no means an expert. All I can offer is my honest assessment of the situation. To Canadian political leaders and government officials receiving this report, including the Prime Minister, I have tried to provide some advice and guidance about steps that could and, in my view, should be taken. But I am also aware (having been in both positions) that there is a difference between giving advice and having to act on it. I remain available to work with those who are asked to implement this report and its recommendations and more broadly to continue to respond to what is an intensely difficult situation. My report offers some personal observations about the challenges of making decisions, about the state of the world as we find it, and what the guiding principles of our foreign policy should be.

In my interim report released on December 21, 2017, I focused on three key issues. In this latest report, which also includes language from the interim document, my findings can be divided into four parts:

- the humanitarian crisis in both Bangladesh and Myanmar as a result of the recent exodus of more than 671,000 Rohingya refugees from Myanmar into neighbouring Bangladesh, adding to the hundreds of thousands of refugees already in that country and the 120,000 in IDP camps and tens of thousands more under virtual lockdown in villages in central and northern Rakhine State in Myanmar;

- the efforts required to ensure the secure return of refugees to their homes with full political and social rights, as well as to ensure the implementation of the recommendations of the Kofi Annan-led Advisory Commission on Rakhine State;

- the need to ensure that the substantial evidence of breaches of international human rights law and humanitarian law are investigated, assessed and enforced in a credible fashion;

- the need for better coordination and joined-up efforts at every level of government and in the international community in order to ensure a successfully focused approach.

My recommendations can be found at the conclusion of the report.

Canada was very much present at the creation of Bangladesh, and we have played an important role in supporting trade, investment, and aid in that country and elsewhere in the region. This is much less true in Myanmar, where we did not open a resident embassy right after partition and independence in 1948 (which we did in India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka), although we did establish diplomatic relations. Ties later became strained under the military regime, but we provided both humanitarian and other assistance to the growing Myanmar refugee population in Thailand and Bangladesh. Canada imposed sanctions in 2007, and we have maintained important parts of our sanctions regime after opening an embassy in Yangon in 2014. Former Canadian federal government ministers John Baird, Ed Fast, and Stéphane Dion have visited Myanmar following the beginning of the reform process, and Aung San Suu Kyi visited Canada as part of a study tour on federalism in the spring of 2017.

The Situation of the Rohingya

Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh / Image source: Global Affairs Canada

Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh / Image source: Global Affairs Canada

To say that the “Rohingya issue” is highly contested is an understatement. There is a full debate about the name, the history, and the current position of the Rohingya population of Rakhine State.

Here are some basic facts about the history of the region: what is now Rakhine State in western Myanmar was at one time the Kingdom of Arakan on the Bay of Bengal. Protected by mountains to the east, the Kingdom’s population was largely of Rakhine ethnicity and Buddhist, with a minority Muslim presence dating back many hundreds of years who call themselves “Rohingya”. When first the British East India Company, and then the British government itself, absorbed Arakan, and then Burma, into the British Empire in the 19th century, Burma was governed as an integral part of India, with no border limiting the flow of people. This led to a significant increase in the Muslim population in Rakhine State, particularly in the central and northern parts of the State. Poor relations between ethnic Rakhine and Rohingya seriously deteriorated in the Second World War when the communities took different sides—the Rohingya with the British, the Rakhine with the Japanese—and tens of thousands of lives were lost in inter-communal fighting. At the time of independence in 1948, citizenship was assured to all those who were resident in the country, and in the early years of civilian government, efforts were made to include the Rohingya population in the political life of the country (they later had their citizenship denied by the 1982 Citizenship Law).

In 1962, a military government led by General Ne Win took over the government. The military has dominated Myanmar politics since that time, with a change in the constitution in 2008 leading to a gradual increase in civilian participation in government. However, Myanmar’s government is unique. The military retains control over three key Ministries—Defence, Border Affairs, and Home Affairs—that are the most important and influential in the context of the internal conflicts in Myanmar and take up a substantial amount of the budget of the country. The military still controls the operations of the armed forces, security apparatus and bureaucracy. The military also has a guaranteed bloc of 25% of the seats in the Parliament, which means it has an effective veto over potential constitutional change.

Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of Aung San who led the Burmese Liberation Army in the Second World War and negotiated independence from the British before his assassination, returned to the country from Great Britain in 1990 and quickly assumed the leadership of the NLD. She spent much of the next 20 years under house arrest, and when she gained her freedom in 2010, she returned to active politics and led her party to a significant electoral victory in 2015, gaining substantial support across the country. Aung San Suu Kyi was not allowed to take control of the government after winning the 2015 elections. She accepted the title of State Counsellor and became Minister of Foreign Affairs. It is an error to think she is either the “de facto leader” let alone the “de jure leader”. In his report, Kofi Annan referred to there being “two governments” in Myanmar—one military; one civilian. That strikes me as right, and therefore requires a deeper analysis of how decisions are made and who is responsible for them.

Myanmar has faced significant internal conflict since independence. Subnational conflict in Myanmar has affected many areas of the country: a large number of mostly ethnic minority non-state armed groups have sought increased autonomy from a militarized central government that sought to impose its will with considerable force. Many hundreds of thousands of people have been killed since 1948. In effect, there has been an ongoing civil war since the early 1950s, geographically concentrated in the states bordering Bangladesh, India, China, and Thailand, all involving a significant degree of ongoing fighting, loss of life, military occupation, and the dispersal of refugees both internally and into neighboring countries. There is still a large internally displaced population, mostly living in camps, as well as a substantial refugee population in Thailand. Since the return of Aung San Suu Kyi to a role in national politics, the peace process has been a key priority of the government, but it is clear that progress in ending military conflict and creating the basis for national peace and reconciliation has been slowed over the last several months. In particular, I would note clear evidence of additional fighting in both Kachin and Shan states.

I describe in section two below the long history of systematic discrimination and human rights abuses suffered by the Rohingya. In August 2016, Aung San Suu Kyi established the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State with Kofi Annan as Chair to make recommendations on improving the conditions in Rakhine State. However, a series of attacks in October 2016 by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (known as ARSA) triggered a heavy-handed military response, leading to violent fighting, the burning of many villages, allegations of rape and violence by the army against civilians, and the forced departure of tens of thousands of refugees. The Kofi Annan Report was published on August 24, 2017, the day before another ARSA attack on police posts and a military base that has been criticized in UN General Assembly resolution (A/C.3/72/L.48) as well as by the UN Security Council Presidential Statement. That attack was followed by a violent conflict and the destruction of more than 300 villages, according to reliable sources. It was at this point that the exodus of more than 671,000 Rohingya began. While this number has been disputed by some in the Myanmar military, it has been verified by UN agencies, which have a long history of monitoring the flow of refugees around the world. In addition, there were further restrictions on movement of those who stayed behind in north and central Rakhine.

Report

The Humanitarian Crisis in Bangladesh and Myanmar

©Suvra Kanti Das / Alamy Stock Photo

The number of refugees worldwide is the highest it has been since the end of the Second World War. The camps near the town of Cox’s Bazar in southeastern Bangladesh are the fastest growing and now the largest in the world. But they are far from unique, and we need to appreciate the extent of what is in fact a global refugee crisis. Issues of internal displacement and migration are everywhere and have created enormous suffering. What we do, or don’t do, in response to the Rohingya crisis will be a litmus test for Canada’s foreign policy.

The UN General Assembly is currently scheduled to deal with two global multilateral compacts, one on migration and one on refugees, this year. These are difficult political, social, and economic issues. But they cannot be ignored. The discussion around both compacts should lead to a deeper global understanding of their importance. Left on their own, refugee and IDP camps will become centres of death, disease, crime, human trafficking, extremism and corruption. It would be unconscionable to ignore these issues or to wish them away. Words cannot convey the extent of the humanitarian crisis people currently face in Bangladesh and Myanmar. I was not refused permission to travel in Rakhine State before I wrote my final report; on the contrary, I was permitted to travel, albeit in a restricted fashion, to the town of Sittwe in central Rakhine, and by helicopter to the border between Bangladesh and Myanmar. This allowed me to see conditions in Sittwe, to meet with representatives of a number of communities, and to engage directly with humanitarian workers who could give first-hand information about the condition of the local population. I took the opportunity to visit the IDP camp in Sittwe and to share perspectives with several people in the camp. I also had the opportunity to travel over much of Maungdaw Township in northern Rakhine and to see the extent of the destruction of the Rohingya villages in the north. It is a truly devastating situation, and there are now further reports based on aerial photography of bulldozing and further razing of houses in villages by the Myanmar military. The Rohingya exodus from Rakhine State in Myanmar has ebbed and flowed over several decades, with the latest surge of over 671,000 since August 25, 2017. While makeshift shelters have been provided on hilly territory near Cox’s Bazar in southern Bangladesh, and a number of UN and other agencies have been doing everything possible to deal with the full impact of the crisis, it is important to stress that conditions are deplorably overcrowded and pose a threat to human health and life itself. Rohingya refugees in this latest exodus have walked for days to get to their eventual destination and arrived malnourished and traumatized. In addition to accounts of shooting and military violence, I also heard directly from women of sexual violence and abuse at the hands of the Myanmar military and of the death of children and the elderly on the way to the camps.

The international agencies working in the camps have repeatedly expressed great concern about the potential for catastrophe in the event of heavy rain and wind, as well as the potential for the outbreak of disease. Based on what I have seen, these concerns are well founded and will require significant additional investments from the international community, including the Government of Canada and concerned Canadian citizens and NGOs, in order to prevent serious loss of life. In response, the humanitarian community, led by the Inter-Sector Coordination Group in Cox’s Bazar and the Strategic Executive Group in Dhaka, Bangladesh, has worked closely with the Government of Bangladesh to draw up a Joint Response Plan for 2018 with a funding target of US$950.8 million. The Plan, which launched on March 16, 2018, lays out a vision for a coordinated response to address the immediate needs of the refugees and mitigate the impacts on affected host communities.

The recent announcement by the Government of Bangladesh that more land is being assigned to camp construction must be matched by additional efforts by the international agencies to find more space for schools, hospitals, health care centres, and centres for women and young children. There is a marked absence of space for such places in the overcrowded, hilly camp I visited, a situation that needs urgent attention. In my view, proposals for new camps should not include the large facility proposed for Bhasan Char, a low-lying, muddy and isolated island off the coast in the Bay of Bengal that is being urgently developed as a “temporary arrangement” for 100,000 to ease congestion at the camps in Cox’s Bazar. Rather, camps should be smaller and reachable by road. At the same time, it must be pointed out that the Government of Bangladesh and the local communities surrounding the camp have made an enormous humanitarian contribution in preparing to host the Rohingya refugees. The entire international community is in their debt, and our aid policy will need to take more account of the extent of this contribution by Bangladesh and the particular needs of those communities that have been severely affected by the arrival of such a large number of refugees in a short space of time.

When I met with a group of women from Bangladeshi host communities whose homes were literally surrounded by the Kutupalong refugee camp, I heard their concerns loud and clear. They found it harder to find work because refugees would take jobs at lower rates; they worried about security and the safety of their children, who no longer made the walk to school, and the higher costs of everything, from food to bamboo; they were concerned about the worsening economic situation, including the serious devaluation of their properties. They told me they were hoping to move as soon as they could figure out where they could go. Their complaints did not sound like the voices of prejudice, but simply expressions of frustration at the extent to which their lives and the lives of their families had been completely disrupted by the sudden arrival of such a large number of refugees.

This situation, no doubt multiplied many times by other voices, poses a clear social and political challenge for the Government of Bangladesh, as it does for the international community. Aid and development assistance must be directed to host communities just as surely as it is to the refugee population itself. To fail to do this is to ensure greater tension and division between the host communities and the refugees.

The condition of women and girls in both the Kutupalong camp and the surrounding community is of particular concern. I heard many allegations of sexual trauma at the hands of both the Myanmar military and those supporting the army. In the overcrowded camp itself abuse is a continuing issue. Poverty leads to increased prostitution and human trafficking. The drug traffic between Myanmar and Bangladesh has long been a challenge, and the arrival of the refugees has provided a cover for increased trade in illegal drugs. This in turn can lead to more abuse and violence in the camp as well as in the surrounding community.

Seeing these words in print makes me realize how inadequate words are to express the extent of the damage and trauma of Rohingya women and girls seeking refuge on both sides of the border. My own interviews with a group of women gave me a detailed and graphic account of abuse and violence, including sexual violence as a weapon of war. These allegations of crimes against humanity need to be addressed directly by the international community, as well as the need for post-traumatic measures to help those who survived this ordeal. Additional resources will need to be gathered to make sure the response is adequate to deal with the extent of the abuse and its consequences. Canada’s new Feminist International Assistance Policy means that our humanitarian response focuses on issues of gender. Canada’s increased attention on sexual and reproductive health and rights and sexual and gender-based violence is welcome and is vitally needed. We are now a leading voice on these issues, and this should continue.

I also discussed with officials the need for new initiatives for schooling. Education in basic literacy skills is lacking, to say nothing of further education for young people who have either been prevented from attending school or whose education has been disrupted by events in Rakhine State. Education is not a luxury item. It is a necessity. Those schools that are up and running are working on several shifts to accommodate the growing population, but new schools are needed to meet the increasing demand. It is hard to imagine a more important investment in providing opportunity and hope to this generation of refugees than providing them with education. This investment will also make it possible to counteract the marginalization and the temptation of extremism that is always present in circumstances such as these.

There is now a better sharing of information about the conditions in the camps, with regularly updated data on nourishment, sanitation, health, and education. There is a clear need for this information to be addressed by action from funding governments and organizations and for clearer lines of authority on the management of all relief efforts. No one can now say “we didn’t know”.

Canada needs to do more to meet the needs of funding of the camp and those responsible for the operation of this vast and complex structure. It is important that we signal that we intend to respond to the regular calls for help from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), in addition to the assistance we provide to particular agencies and NGOs whose work corresponds to our government’s policies and focus. I would urge that Canada take a stronger lead on education and infrastructure needs in the camp, as well as the necessary work on sexual trauma and the condition of women and girls. I was very glad to see the latest instalment of aid being provided by Canada, bringing our humanitarian assistance to Bangladesh and Myanmar to nearly $46 million since 2017. Now is the time to commit over a longer period of time, as we have done in other refugee crises in Syria and Iraq.

The Political Situation in Myanmar

Destroyed villages in northern Rakhine State / Image source: Global Affairs Canada

It is striking that the demands of the Rohingya for citizenship and full recognition in the constitution do not appear to have substantial popular support among the general public in Myanmar. There are many different explanations for this attitude toward the Rohingya population, who many in Myanmar refer to as “Bengalis” as a term emphasizing their “foreignness”. Pope Francis was advised during his November 2017 trip not to use the term “Rohingya” because it is seen as a term that implies a connection to the land in Rakhine State and because there is a demand from the Rohingya that they be recognized as an official indigenous nationality of Myanmar within the constitution. In Bangladesh, they are not referred to either as “Bengalis” or as “refugees” so as not to imply a more permanent presence. It is important to understand that the process of discrimination against the Rohingya people has been persistent and cumulative and has led to the present crisis. The process of their legal exclusion from full citizenship has been going on for some considerable time and now means that the overwhelming majority of Rohingya are stateless. This has not been a bloodless process. It has brought with it much loss of life, injury, pain, loss of property and loss of livelihood, to say nothing of the fear and humiliation that comes with this extent of discrimination. This also speaks to the issue of “genocide”, a word that is so full of historic meaning and which I will address in the next section of my report.

This situation affects current relationships in all of Rakhine State and in Myanmar. Rakhine State has a diverse ethnic population. The ethnic Rakhine make up the majority, followed by a considerable population of Rohingya as well as other ethnic minorities.

The Rohingya population has made up the significant majority in the north of the State (the three townships that have now been largely evacuated), a large group in central Rakhine (those who have not yet left in such large numbers, but who face significant restrictions on their movements, and at least 120,000 people in IDP camps) and a much smaller group in the south. Politically, the government in Rakhine State is controlled by the pro-Rakhine Arakan National Party, not by Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD, which won an overwhelming majority throughout Myanmar at the last election—except in Rakhine. However, it must also be understood that the central administration of the country has appointed a Chief Minister, and the local governments down to the village level report to the Minister of Home Affairs, who is a member of the military. Having met with the Minister of Home Affairs, I was left in no doubt as to the extent of control of the central government over local affairs, another significant source of tension with the Rakhine State political leadership.

There is a Rohingya population in central Rakhine that has been subject to what is, in effect, a military occupation since 2012. They are either living in an IDP camp or are confined in villages where they are under strict military curfew. These conditions are a clear breach of their human rights. More recently, representatives of the international community, including UN agencies, were not, for many months, permitted access to these communities, and there are reports from those few able to witness these conditions at close quarters that the Rohingya population is subject to malnourishment as well as the denial of the right to free speech, to freedom of association, to freedom of movement as well as a denial of access to education, health care, and social services. Reports of how bad these conditions are will continue to filter out and may become more widely available as officials of the UNHCR and UN Development Programme (UNDP) are granted more access to the region. But the reality of a genuine and deep threat to human security and even survival cannot be denied.

I was permitted access to Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine State, the week of February 4, 2018. What became immediately apparent was the deep resentment of the very presence of the Rohingya population in Rakhine by some ethnic Rakhine and the extent to which international and other efforts to establish a humanitarian dialogue are, in fact, deeply resented. It is this hatred that in my view poses the greatest threat to any possibility of a safe and dignified return for the Rohingya who are currently living in Bangladesh and indeed threatens the lives of those Rohingya who are still in central and northern Rakhine.

There are few outside witnesses to the full extent of the military operations and the conditions facing those Rohingya still left in Rakhine State. Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times was able to visit a number of villages, and in an article dated March 2, 2018, he describes conditions of deep poverty, malnourishment, and profound isolation that he refers to as a “slow genocide”. Other international observers present are few and far between, and their freedom of movement is severely restricted. However, what reliable information is available points to an ongoing crisis in both human rights and human security.

It is important to appreciate the depth of the challenge facing the Rohingya community. They do not have the protection or presence of an international force, or even outside observers. Because much of northern Rakhine State is a conflict zone, international humanitarian assistance has been actively restricted and is only now resuming in parts of the State. The army asserts the right to enter any home at any time to search for ARSA militants or others opposed to the current regime, and there are serious allegations of breaches of basic civil rights, as well as beatings and torture that to this point have not met with credible investigation or consideration by authorities in Myanmar.

The conflict is not just between the Myanmar Army and ARSA. It also involves both the Rohingya community and the ethnic Rakhine where there are allegations of attacks on the ground between the two groups. Again, the absence of neutral observers makes fact finding difficult. The departure of such a large number of people can only have been created by a climate of fear and intimidation, whatever its source. It is also important to point out that the entire state of Rakhine is deeply impoverished. The competition for land and resources is so intense precisely because everyone is so poor. One of the reasons the delivery of assistance to the Rohingya population has met with such fierce local opposition is that “development” is something the local Rakhine population feels is only for others, i.e. the Rohingya, and not for them. That is something that has to change.

The Kofi Annan Commission made a number of recommendations that the Myanmar government has indicated a willingness to accept. The implementation of the recommendations is now in the hands of a committee under the leadership of Minister for Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement Win Myat Aye. In addition, the Government of Myanmar has established a Union Enterprise for Humanitarian Assistance, Resettlement and Development in Rakhine, representatives of which I met on November 8, 2017, in Yangon, Myanmar. This group has, at the present time, uncertain resources, although the government speaks about a “public private partnership”. The focus of this Union Enterprise is on physically rebuilding the region so badly affected by the violence and creating the conditions that will allow for the voluntary repatriation of the Rohingya population currently outside the country. Unfortunately, the current crisis has stymied progress in implementing Mr. Annan’s recommendations, which have been strongly supported by countries like Canada.

The Government of Myanmar announced the appointment of an advisory board on the implementation of the Kofi Annan report, with five members appointed from the international community. This board made its first visit to the region in the third week of January 2018. One of the international members, Bill Richardson, left the board after expressing his strong concerns about policies of the Myanmar government. I have spoken with other members of the board who have expressed their strong commitment to an independent and objective assessment of the work of the board and the policies of the Myanmar government.

In addition, since my interim report, there have been further developments in discussions between Myanmar and Bangladesh, with the signing of three arrangements on the repatriation of the Rohingya population to Myanmar. In considering the significance of these documents it is important to understand that the two countries have reached a number of agreements since the 1970s. Rohingya refugee crises are not new. Unless this crisis is handled in a different way, there will be more crises, with more violence, loss of life, and hardship to come.

The Secretary-General of the UN has said that any return has to be “voluntary, safe, dignified, and sustainable”. Canada and like-minded countries have delivered similar messages. It is crucial that both Bangladesh and Myanmar not only commit themselves to these principles, but also to the steps that will be required to ensure their implementation. In particular, the UNHCR has to become a full partner with both governments in ensuring that these principles become a reality. Unless that happens, it would be wrong for the international community to sanction the return of the Rohingya refugees. To return to a world of marginalization, discrimination, extraordinary hardship and potential violence is not something that can be countenanced. At the time of writing, the Government of Myanmar has apparently agreed in principle to sign a trilateral MOU with the UNHCR and the UNDP to work in northern Rakhine on repatriation, resettlement and development. At the same time, there are reports of possible legislation that would hamper the work of NGOs and the UN. It must be clear to all concerned that unless international observers, including UN agencies, are allowed to move freely, provide assistance, and observe what is happening, it is simply not possible to have confidence that the Rohingya population in Myanmar will be properly protected.

The steps that need to be taken must also include full access by the UNHCR and other agencies to all places in Rakhine State where the local population—i.e. all ethnic and religious minorities—asks for contact and protection. This has not been the case for a long time, and will require a change of policy and position on the part of the Government of Myanmar, both civilian and military. The real roadblocks to resettlement are about more than housing. They have to do with the nature of the conflict that has led to the most recent fighting, a conflict that is at its heart about the ability of the Rohingya to be welcomed inside Myanmar as a legitimate partner in the Myanmar nation. The long-standing disputes about identity cards, land, economic livelihoods, citizenship and freedom of movement have grown worse in the last several years and have led to the further marginalization and violent displacement of the Rohingya population, to say nothing of conflict, violence, and loss of life.

This is not a short-term problem with a quick fix. The fact that arrangements have been signed between the governments of Bangladesh and Myanmar is a first step in a possible process of repatriation, but there are several additional assurances and guarantees that have to be provided before such an agreement can be implemented. There is also the challenge of resources at the border assessing re-admittance, as well as the conditions that await the returnees in Rakhine State. And the issues of political participation and citizenship loom large over the whole picture.

The notion that these are all issues of absolute sovereignty, to be settled exclusively between the governments of Myanmar and Bangladesh, misses the point that the UN General Assembly has recognized: the duty to protect the security of individuals is initially the duty of states, but failing that becomes a wider regional and, ultimately, international obligation. This does not imply necessarily a military confrontation with the Government of Myanmar. It does mean a much deeper acceptance by that government to an international presence that will ensure basic principles of human rights are being upheld. This cannot happen without engaging the Government of Myanmar and continuing to seek from that government the necessary changes. These are all principles that the Government of Myanmar has accepted by joining the UN and by accepting the foundations of the Charter and the principles of the international human rights architecture since its independence in 1948. We should hold that government to its commitments. Government leaders in Myanmar are not being asked to sign on to an agenda that is imposed on them. It is an agenda that they have agreed to accept.

The final report of the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State, “Towards a Peaceful, Fair and Prosperous Future for the People of Rakhine”, provides a comprehensive set of recommendations to achieve lasting peace and prosperity in Rakhine, including in the following areas:

Socio-economic development: Foster benefits for local communities from investment in Rakhine and encourage participation in decision-making on issues related to development.

Citizenship: Accelerate the citizenship verification process in line with the 1982 Citizenship Law and ensure it is voluntary. There is also a need to revisit the law itself.

Freedom of movement: Ensure freedom of movement for all people irrespective of religion, ethnicity or citizenship status.

Communal participation and representation: Promote communal representation and participation for under-represented groups, including ethnic minorities, stateless and displaced communities. Include women in political decision-making. Simplify registration processes for civil society organizations.

IDPs: Develop a comprehensive and participatory strategy on closing all IDP camps in Rakhine State. Ensure that the return/relocation of individuals is voluntary, safe, and dignified. Meanwhile, guarantee dignified living conditions in the camps.

Cultural development: Ensure Mrauk U’s eligibility as a candidate for UNESCO World Heritage Site status. List and protect historic, religious and cultural sites of all communities in Rakhine.

Inter-communal cohesion: Foster inter-communal dialogue at all levels— township, state and union. Activities that help to create an environment conducive for dialogue should be initiated by the government, including joint vocational training, infrastructure projects and cultural events, and the establishment of communal youth centres.

Security of all communities: Develop a calibrated response that combines political, developmental, security and human rights approaches, addresses the root causes of violence and reduces inter-communal tensions. Enhance the monitoring, performance and training of security forces, including in human rights, community policing, civilian protection and languages.

Bilateral relations with Bangladesh: Further strengthen bilateral cooperation.

The Question of Accountability and Impunity

Child in the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar / Image source: Global Affairs Canada

Since the end of the Second World War and the founding of the UN, the world has been involved in the establishment of basic standards of international law that are intended to ensure that crimes involving threats to human life and security do not go unassessed and unpunished. Those who are responsible for breaches of international law, including crimes against humanity, should be brought to justice. This applies to all those involved, including state actors and non-state actors, armies, and individuals.

The UN Human Rights Council has appointed an independent international fact-finding mission to establish the facts about alleged recent human rights violations and abuses by military and security forces in Myanmar, in particular in Rakhine State against the Rohingya, but the mission has not been permitted to visit Myanmar or to interview officials in the army and government, or representatives of ARSA, who could respond to the serious allegations about what has been happening, particularly since 2012. The mission has been permitted to interview members of the Rohingya community living in the camps near Cox’s Bazar and will be producing a report based on these interviews. Pramila Patten, the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Sexual Violence in Conflict, has also been gathering important information. I have had the opportunity to meet and talk with both members of the fact-finding mission and Ms. Patten, as well as Yanghee Lee, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar.

Eye witness accounts that I have heard have been both chilling and graphic. Many human rights organizations and other NGOs have also shared similar accounts, and they have been the subject of widespread attention and condemnation. It is now time for the world to move beyond reporting graphic allegations to the tough challenge of gathering evidence and protecting that evidence for use in possible trials in the future. I urge Canada to work directly with other governments to find a suitable and effective way to ensure this will be done.

The position of the Government of Myanmar—refusing entry to the UN Human Rights Council’s fact finding mission, the same Council’s Special Rapporteur, as well as numerous human rights groups, and representatives of several countries and insisting on its unimpeded right to bulldoze land and carry out its own investigations—hardly gives confidence to a rigorous process consistent with the basic principle of international law that no person or institution should be a judge in its own case and that crime scenes should be kept intact for proper, objective investigation. The gathering of evidence about particular events has to be thorough and systematic and relate to specific events, in particular places, at particular times. This work needs to look at events over the last several years, and efforts must be made to link them to those responsible for such violence and abuses of human rights and security. This cannot only be done by the Myanmar military judging its own cause.

Canada must remain involved in this legitimate and important international work. There are already a number of NGOs that are making compelling legal arguments about the nature of the threats and treatment that people have received—and given our experiences with mass crimes in the past several decades, it is critical that this work be supported. I have been impressed by the degree of engagement and commitment that has been shown by so many groups and individuals in Canada. The full range of responses—humanitarian, on-the-ground volunteer work, fundraising, as well as detailed policy representation—has been remarkable and has greatly assisted me in my work. I remain open to meeting people in the time ahead, and I know these meetings will have a direct effect on my work.

There is a difference between information, intelligence, allegations, and reliable evidence that can be used to prosecute individuals. We are at the point where it is the gathering of actual evidence that is crucial. It is also important that Canadians remain aware of the necessary tension between the need to engage with the people and Government of Myanmar and our ongoing advocacy for human rights. We have been publicly associated with the peace process in which the Government of Myanmar is negotiating with dozens of ethnic armed groups to end decades of multi-front civil war, with the dialogue on governance and pluralism, and with a number of other critical issues; this engagement needs to continue. This requires that we respect the full range of opinions in Myanmar and within Myanmar civil society, but it should never mean that we abandon our commitment to the truth about what has happened or our commitment to rejecting any ambivalence to the primacy of the rule of law.

I have been struck in my discussions with both military and civilian officials in Myanmar that they often use the phrase “rule of law” in their comments. We need to be clear that “rule of law” and “law and order” are not the same thing. The latter implies a willingness to accept that laws can be passed that are repressive or exclusionary and misses the key point that we associate with the phrase “rule of law”: the fundamental principle that no one, including the political or military executive, is above the law. “No matter how far you rise, the law is always above you” is a fundamental precept that should never be overlooked or forgotten. The treatment of the two Reuters journalists, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, by the Government of Myanmar has raised widespread concerns in the international community about the fairness of proceedings, the denial of bail, and how a law from the repressive past of the British Empire could today be resurrected to be used in circumstances where they were drawing attention to potentially criminal behaviour by the armed forces.

I have had a number of discussions with scholars, activists, and many officials in several countries and UN institutions. On the basis of the allegations that are now widespread, it is clear that a strong case exists for the presumption that a number of crimes against humanity have been committed in Myanmar. These allegations include abuses by members of the Myanmar military, militia and other groups, and ARSA, among others. The crime of genocide has also been alleged, and the evidence for this crime has to be assessed carefully as well.

The lesson of history is that genocide is not an event like a bolt of lightning. It is a process, one that starts with hate speech and the politics of exclusion, then moves to legal discrimination, then policies of removal, and then finally to a sustained drive to physical extermination. The people of Myanmar and the entire world community need to be mobilized to ensure that the Rohingya do not join the tragic list of those people who have died because they were singled out for their identity. Everyone needs to understand what is at risk here—which is why the issues of reconciliation and political leadership are so important.

The definition of genocide in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) is:

“Any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

It should be noted that the crime of genocide requires proof of “intent to destroy a group”. Crimes against humanity, also listed in the Statute, do not require proof of such intent, but refer to a number of offences as part of a widespread or systematic attack, including murder, deportation or “forcible transfer of population”, as well as grave sexual violence, torture and persecution against any civilian population. In this section, I shall be referring to the steps that could be taken to gather the evidence required to meet the thresholds for the proof of these crimes.

My point here is to emphasize the gravity of the potential offences that arise from the mistreatment of the Rohingya population by the government, military, and other individuals and organizations over many years and, in particular, over the last several months. There is no way for us to turn away from the importance of these issues.

Once evidence is gathered, the question naturally arises: where do these investigations take us? Myanmar is not a signatory to the Rome Statute, but Bangladesh is. There is also the principle that “universal jurisdiction” can be applied in a number of countries where there is national legal acceptance of the application of fundamental human rights principles. There will continue to be many legal arguments and debates that may lead to practical conclusions.

Two additional ideas in particular are worth pursuing. The first is that “forcible deportation”, which is a named offence in the Rome Statute, is arguably an offence that is only completed, in this instance, when refugees physically leave Myanmar territory and enter Bangladesh. It is arguable that this gives some jurisdiction to the ICC, because Bangladesh is a signatory to the Rome Statute. Whether this would lead to the increased likelihood of a conviction is another matter, and is a decision for the ICC prosecutor based on a careful assessment of the evidence.

The second proposition that in my view has considerable merit would be the establishment of a mechanism by the UN General Assembly—similar to the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM or “Triple I-M”) headed by Catherine Marchi-Uhel to deal with numerous allegations in the Syrian conflict—thereby ensuring a comprehensive and systematic approach to what has taken place in Myanmar. In addition, establishing such a mechanism presents several political, diplomatic and legislative challenges. This also doesn’t deal with the issue of what tribunal could be set up to deal with cases arising from the investigation, but it does at least ensure an approach to evidence gathering and preservation that would take us beyond the world of allegation and denial. In many other historic conflicts—notably Cambodia—specific tribunals have been established and, however imperfect, have gone some distance to dealing with the problem of impunity. It is, as they say, better than nothing.

This brings me to the question of sanctions and other mechanisms of policy. Canada first introduced sanctions against Myanmar in 2007 under the Special Economic Measures Act. These were relaxed somewhat in 2012 following positive steps toward reform in Myanmar. However, it is important to stress that Canada did not relax sanctions as completely or comprehensively as the United States and European countries. For example, we still have a ban on arms sales and limitations on cooperation with the Myanmar military and companies and institutions associated with the military.

The governments of Canada and the United States have legislation in place—known as the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act in Canada and the Magnitsky Act in the United States—that give these governments the power to name individuals deemed responsible for human rights and other abuses and to issue travel bans, freeze assets, and take other measures against these named individuals. Both governments have named Major-General Maung Maung Soe, who was the head of the Myanmar Army’s Western Command, and in so doing have made it clear that others can be added to the list. This could include, in my view, anyone deemed to share responsibility for the abuses of human rights and the crimes against humanity in Myanmar.

Several other suggestions have been made about further “isolating” and “pressuring” Myanmar, up to and including breaking off diplomatic relations and all financial, trade, or development assistance to the country.

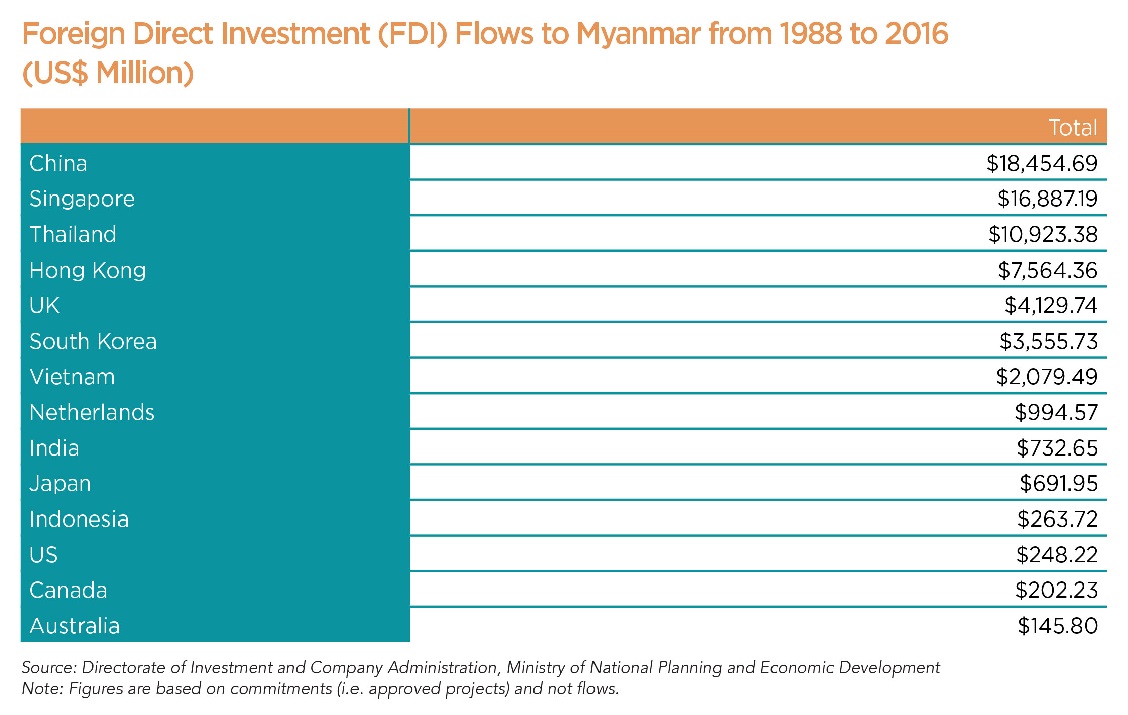

A realistic analysis would strongly support the proposition that wider sanctions against Myanmar were unsuccessful in the past and in fact have only had the effect of making Myanmar more reliant on assistance and investment of all kinds by China and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) partners.

Myanmar is an impoverished country of 50 million people that has been mired in internal conflict and indeed civil war since its independence in 1948. To cut off development assistance to or collaboration with the entire Myanmar public sector or to stop engaging with the Government of Myanmar would have the effect of making Canada almost entirely irrelevant to any debate or discussion on how to move forward. To critics who say, “Well then, it’s business as usual,” I would emphatically reply that this is not the case. It is an approach to human development that does not use a poor population as a pawn in our profound differences with the Government of Myanmar about what has happened and is still happening in the country.

We must be cognizant of our leverage and not allow our foreign policy to be beholden to a policy of empty gestures. We need to continue—and indeed to deepen—our commitment to human rights on the ground in Myanmar, to any processes of reconciliation that seem to be working, and to the rights of women and girls who are living in difficult circumstances.

Effective Coordination and Cooperation

I have been struck in my work by the challenges we currently face in dealing with a crisis of this suddenness and magnitude. There were many early warnings of the possibility of this happening, but it must be said that these warnings did not lead to an effective international reaction. For some time (and particularly since the tragic events in the Balkans and Rwanda), many have insisted that the ability of the international community and its agencies to respond to humanitarian crises must meet the challenges. We have to admit that for all the discussion about the “responsibility to protect” and the work of the UN and its agencies, the world was slow to heed warnings, to see the clear signs of crisis, and also slow to respond in an effective and coordinated manner. In the Balkans, for example, it took a long time for the international community to respond. In Rwanda, the world turned away as warnings came loud and clear from officials on the ground about the impending disaster. The intervention in Iraq against Saddam Hussein was led by the United States and the United Kingdom, but had a disastrous outcome. It could be argued that the intervention in Libya was equally unsuccessful in providing stability. And in Syria, the failure to intervene has led to the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives and millions of people displaced and dispersed.

We have ample examples of how not to intervene as well as examples of the costs and consequences of doing too much and doing too little. Hindsight is easy, but we need to respond to this crisis in a way that will save the most lives and provide the best opportunity for stability, security, and opportunity for the whole population.

George Bernard Shaw once suggested that the biggest problem in communication lies in assuming it has already happened.

This insight helps to explain how vertical silos are a problem for any large organization. Communication and coordination become more necessary because without them consistent work is impossible. The silos themselves are often not accidental. They are there for a purpose: to maintain turf and power bases, to keep difficult issues less than transparent, and to conceal incompetence or serious mistakes or even wrongdoing. The depth of this problem affects organizations and governments at every level. Any successful resolution of the current crisis in Bangladesh and Myanmar will require a sustained effort at breaking down silos wherever they are found. And they are everywhere.

These silos exist in the Myanmar and Bangladeshi and other governments as well as in the UN, its agencies, and in the large international NGOs that are responding to the crisis.

There has been some improvement on the ground in the largest refugee camp in Bangladesh in achieving greater cooperation between all those providing services, as well as between the UN and non-governmental agencies and the Government of Bangladesh and donor countries.

On my first visit to the Kutupalong camp in November 2017, I was struck by the existence of organizational phenomena only too familiar: lines of command and direction that were unclear, battles over turf and jurisdiction, and finger pointing at anyone not in the room for the failures to address the problem. There were noticeable improvements by the time I visited a second time, but we need to understand that the annual spring storms and rain coming will produce even more serious crises than what we have seen so far. Emergency preparedness in both countries needs to improve dramatically to take full account of what we know from experience can happen. We do not have much time. International agencies also need to be fully apprised of the risks, as do national governments and agencies, both civilian and military, which could play a supportive role in the event of an even more serious disaster.

In Myanmar, the cross-ministry task forces set up to deal with resettlement issues are encouraging, but the physical and infrastructure decisions are ultimately less important than the need to deal with the underlying political issues in Rakhine State itself. The conflict between ethnic Rakhine and Rohingya in Rakhine State dates back centuries and is now extremely intense. This situation is complicated by the sense that the ethnic Rakhine comprise a minority that itself has difficulty being heard in Myanmar and because underdevelopment in Rakhine has been chronic and has not been successfully addressed by the central government. All these issues need to be faced; only then will any kind of successful repatriation be possible.

Kofi Annan’s report rightly focused on these questions. Ironically, it was published the day before the outbreak of the deepest military conflict to date and the departure of more than 671,000 Rohingya to Bangladesh. But what Mr. Annan started must continue. The implementation of his report, along with further practical efforts to deal with the crisis, will need the active support of the international community. Every effort to build common ground and to break down prejudice and hatred must be made and supported. The challenge in this situation (as in so many others) is to stop the extremists on all sides of the argument from running away with the agenda. There are still signs that many people believe in reconciliation, but are afraid to raise their hands. Giving courage to those seeking peace should be a priority for the world community, including Canada.

In both Myanmar and Bangladesh, we need to ensure that our aid and assistance are not directed exclusively at any one ethnic group or nationality. In particular, we need to be aware of the danger that the international community is being portrayed by interests in both countries as “only caring about the Rohingya”. In both Rakhine State and in the area around Cox’s Bazar, we need to be sure that the scope of our funding includes other communities as well as the Rohingya and that we understand that the wall between “humanitarian assistance” and “development” needs to be broken down.

A truly optimistic but not impossible scenario would see a number of countries, including Canada, working with both Myanmar and Bangladesh as well as the Rohingya community and the government of Rakhine State, to see what can be done to persuade the World Bank and Asian financial agencies to assess the possibility of pursuing serious development opportunities on either side of the Myanmar-Bangladesh border that would begin to address the severe challenges facing this entire region. Electrification, infrastructure improvements, education and human development—these are all fundamental to dealing with the extent and degree of underdevelopment in the region. But let me be clear again: this development depends on addressing the underlying human rights issues that have led to the exclusion, incarceration, and deportation of the Rohingya people. Rights and development must go together.

There are differences of opinion about the relative importance to be attached to rights promotion and enforcement and the need for effective engagement with countries whose laws, customs, and ways of doing business are different from ours. There is said to be a difference between “humanitarian aid” and “development assistance”, and within the aid community itself there is an understandable resistance to “political interference” as opposed to development goals. It is now a general principle of our foreign policy that it is to be feminist in its focus. Given the extent of gender discrimination and inequality in the world, this is completely laudable, but other focuses—on conflict prevention, constitutional advice, mediation, and economic and social development—need to be maintained as well. The current conflict in Myanmar and its impact on Bangladesh gives us an opportunity to find the necessary common ground in our own policy and that of many other like-minded countries and agencies to overcome some of the silos and compartmentalized thinking that can get in the way of problem solving.

In the case of the current crisis in Rakhine State and beyond, the issue for the Government of Canada and other governments, as well as for the UN itself, is how to ensure that all of our engagements meet the twin tests of principle and pragmatism. To suggest that we have to choose one or the other is wrong-headed. If there is no realism and effectiveness in our pursuit of principle we are doomed to ineffectual rhetoric that might make us feel better but will do little to improve the actual situation on the ground. If we lose sight of our principles, we are simply acceding to an agenda that grants no importance to the advancement of rights and the rule of law.

Richard Haass, the President of the Council on Foreign Relations, has described the world today as being in “disarray”. It would be fair to say that many of the assumptions of what could be called the post-war consensus have been called into question. Canadian foreign policy has, over the years, recognized the growing importance of Asia, and we have expanded commercial and other ties with the leading powers in the region.

Our current aid program in Myanmar focuses on peacebuilding, assisting civil society, and projects focusing on local economic development. Including the ambassador, there are six Canadian employees and seven local staff at our embassy in Yangon. We have no office in Naypyidaw, the official capital, and in my view over time this is a step we might wish to consider, since a number of other countries are following that route.

The conflict in Myanmar reflects a number of conflicts that are happening throughout the world. Deep and often intractable intercommunal conflicts are arguably at the core of the worst violence in the world today. Developing a clear strategy for conflict and crisis resolution should be a clear policy objective for ourselves as well as for the international community. It is a complex puzzle, but if we want to be effective we have to be prepared to engage with a world that is changing. Sometimes countries make speeches and decisions as if their voices alone are the deciding factor in determining outcomes. We should avoid that illusion and share that perspective with others.

We often talk of peacemaking and peacekeeping as being hallmarks of Canadian foreign policy since the end of the Second World War. Having been present at the creation of so many key achievements—in human rights, the rule of law, the UN Emergency Force, the list is long—Canada has a particular obligation to ensure that the costs and consequences of this inheritance are lived up to. Conflicts within countries quickly become conflicts between countries and have wider regional impact. The Rohingya crisis is just such an example.

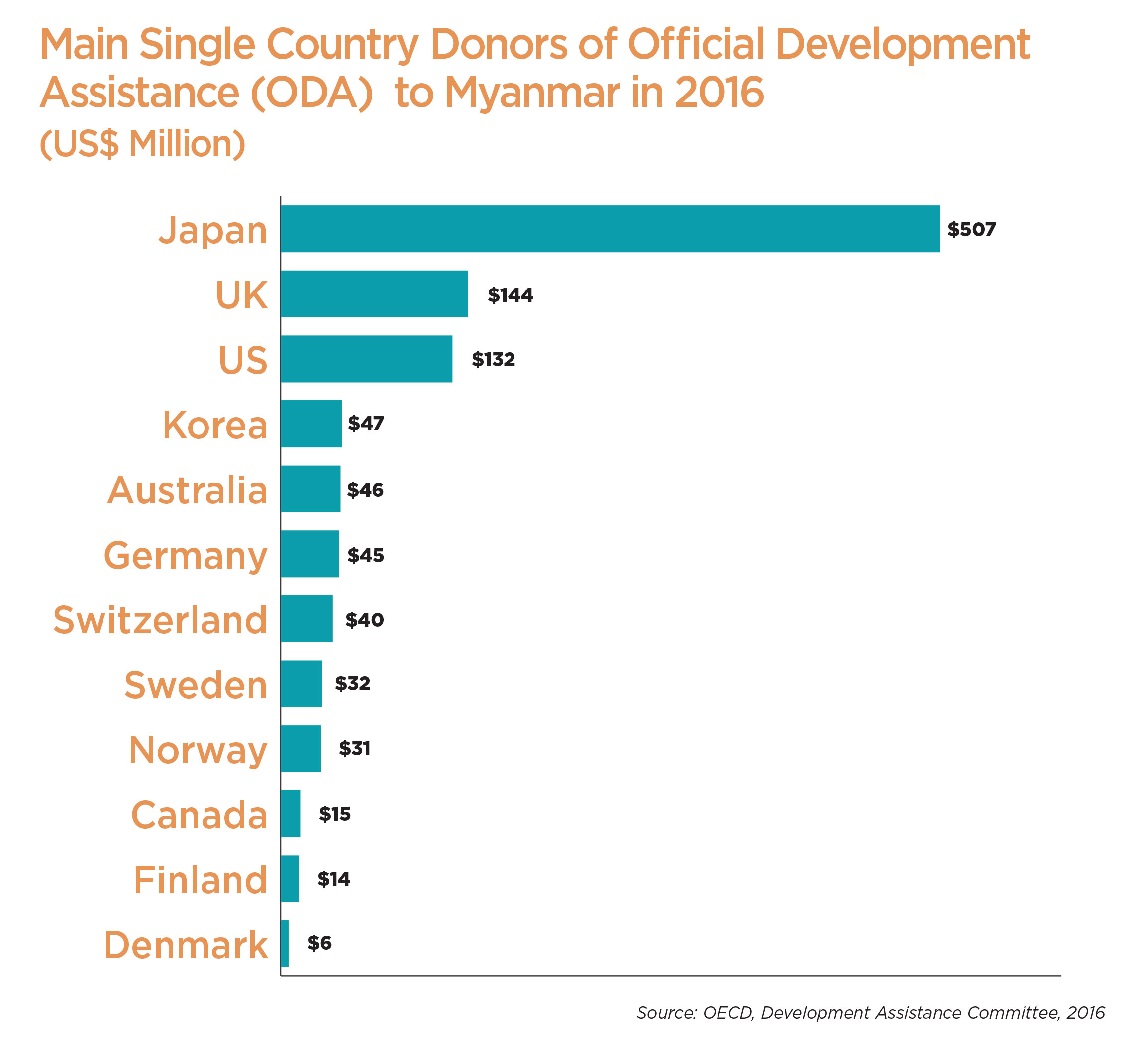

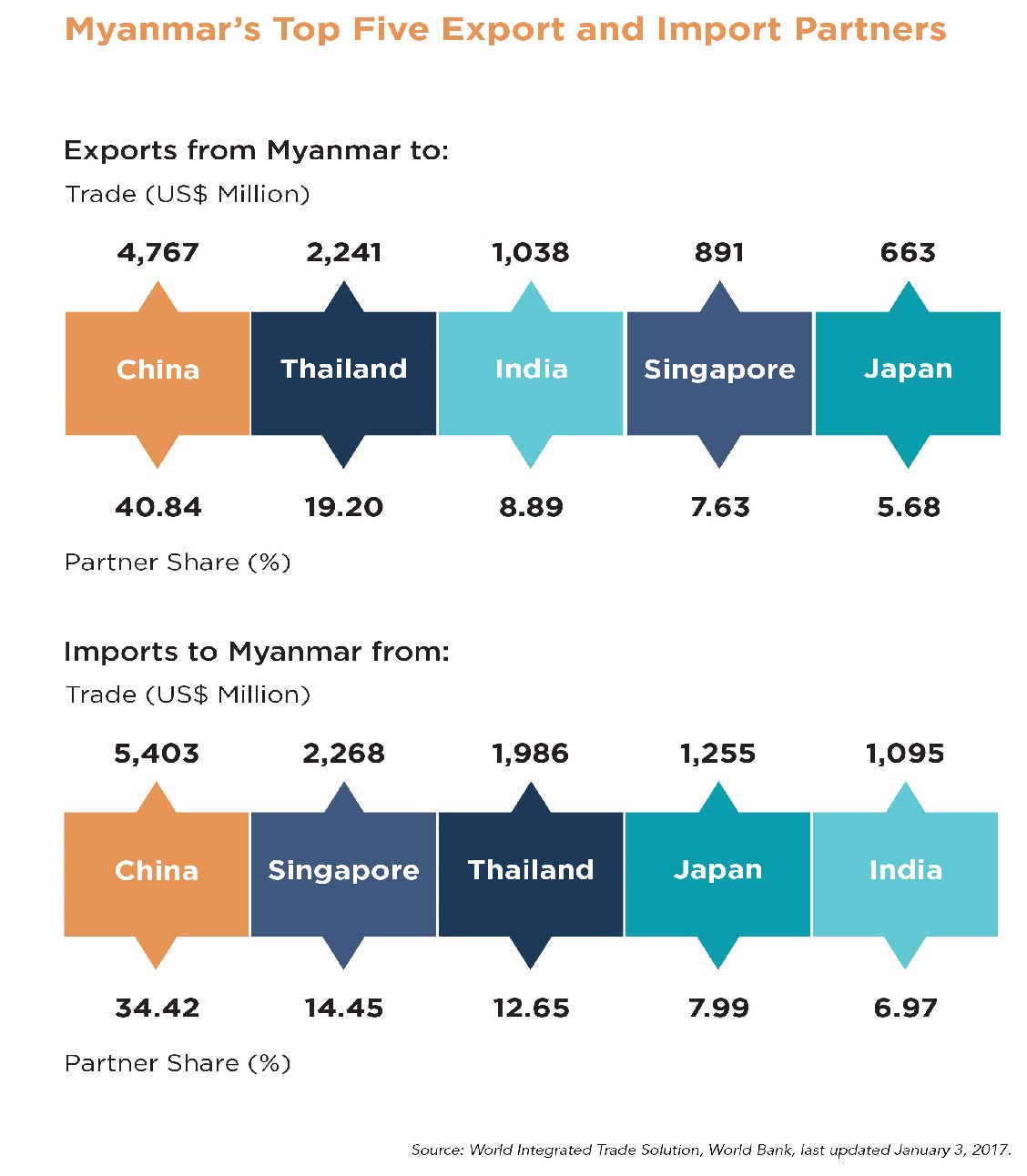

Regional dynamics need to be taken into consideration as we respond to the crisis. There is no doubt that China is currently playing a key role in Southeast and South Asia, as it is in the wider world. It is an investor in both Myanmar and Bangladesh. It has a significant infrastructure vision for the whole region, called the Belt and Road Initiative. It has proposals for dams, ports, roads, and railways that involve all the countries in the region, including Myanmar and Bangladesh. The bilateral relationship between China and Myanmar, both military and civil, is deepening: China supplies 70% of Myanmar’s military equipment, and its businesses are everywhere in the country.

India and Thailand are key neighbours, investors and influencers. Japan is a major donor. Indonesia is an increasingly important player in the region, and so is Turkey. The Gulf States, Saudi Arabia and other Islamic countries are important sources of investment, charitable assistance, and remittances from Rohingya and others who have been working in these countries.

I am also convinced that the focus on the immediate humanitarian crisis needs to include a medium- and longer-term approach, which would include development assistance, political and governance support, as well as efforts to move forward on issues of accountability and impunity. Just as Canada needs to make strategic decisions on whether, and to what extent, it intends to give priority to this issue, so too it needs to make efforts to work with like-minded countries on some common and coordinated approaches. This will extend beyond some traditional partners to include countries in the ASEAN region as well as in the Islamic world. I would note that the Rohingya crisis has met with a strong reaction from many different countries, but it is now vital that this reaction leads to a coordinated effort and the resources required to make a difference.

The Canadian government should establish a Rohingya Working Group, which would extend across government and beyond to relevant NGOs, in an effort to ensure an effective rapid response to deal with the potential humanitarian crisis that will follow bad weather. This will involve an ongoing effort with both Bangladesh and Myanmar to ensure that international assistance is more streamlined, effective and not blocked by bureaucratic rigidity or political posturing.

Conclusion

Special Envoy Rae in the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar / Image source: Global Affairs Canada

Our first obligation is to protect lives. Meeting this obligation will require presence, perseverance, and patience: presence because we cannot cede the entire terrain to those whose commitment to individual freedom and the rule of law has been found badly wanting; perseverance because our efforts will be met with resistance, denial, and at times a refusal to engage; and patience because it will take longer and will require more effort than we currently appreciate. There are no guarantees of success, and many lives are still in the balance. But one thing is certain: if we fail to try, the results will be far worse than if we make the necessary effort.

Recommendations

The Humanitarian Crisis in Bangladesh and Myanmar

- A fundamental principle of Canada’s approach to the Rohingya crisis should be that we listen to the voices of the Rohingya themselves. This principle should guide our actions and inform our advocacy.

- Canada should take a leadership role in responding to the current crisis by stepping up humanitarian and development efforts in Bangladesh and Myanmar. Canada’s response should focus on providing humanitarian assistance, education, supporting infrastructure, and mitigating the impact of the violent deportation on Rohingya women and girls by providing strong support to UN and other international organizations working in camps and elsewhere. Education in particular should become a priority for our longer-term approach. The Government of Canada should develop a multi-year funding plan starting in 2018-19 for this comprehensive work on both sides of the border. This multi-year plan should further include the necessary work on accountability and the gathering of evidence and the increased coordination effort required both domestically in Canada and globally. I estimate the increased annual cost of this combined effort, including for additional staff at headquarters and abroad, at $150 million for the next four years.

- While expressing our gratitude and providing much needed support to the Government of Bangladesh, Canada should be making clear its urgent concern about the need for additional land in and around Cox’s Bazar for the 100,000 Rohingya refugees deemed to be at risk of death or serious illness as a result of flooding, landslides, and water-borne diseases expected to be brought by the upcoming monsoon season. The 500 additional acres of land that the Government of Bangladesh has recently allocated are not sufficient to deal with the extent of the crisis. Similarly, the construction of the island camp of Bhasan Char by the Government of Bangladesh is unlikely to be completed in time or to be sufficient to deal with the extent of the expected crisis; it also raises serious issues about accessibility and mobility. The extent of the urgency of the humanitarian crisis and the real risks to the Rohingya and other populations in both Bangladesh and Myanmar need to be more widely publicized and appreciated. The continuing issues relating to acquiring visas and work permits for humanitarian workers must also be addressed and resolved by the Government of Bangladesh.

- In this multi-year plan, Canadian development assistance should not only focus on the needs of Rohingya refugees, but also take into account those of the Bangladeshi population in Cox’s Bazar, noting the impact that the arrival of an additional 671,000 refugees has had on the resident population. Canada should continue to work with organizations committed to development as well as human rights.

- Canada should continue to urge the signing of an MOU between the UNHCR, the Government of Bangladesh and the Government of Myanmar, and the establishment of stronger relations between all the UN and international agencies with both governments. Implementation of these plans and, in particular, allowing aid, assistance, observers as well as sustained and unfettered access to Rakhine State would go some way to reassuring both the Rohingya population and the international community of the sincerity and credibility of the commitment of both the civilian and military wings of the Government of Myanmar to an effective plan for the return of the Rohingya population.

- Canada should signal a willingness to welcome refugees from the Rohingya community in both Bangladesh and Myanmar, and should encourage a discussion among like-minded countries to do the same. This in no way lessens the obligations of the Government of Myanmar to accept responsibility for the departure in such violent circumstances of the Rohingya population from their homes.

- Canada should provide support to informal initiatives fostered by experienced NGOs intended to improve dialogue between the governments of Myanmar and Bangladesh, and reconciliation between the ethnic Rakhine and the Rohingya. These initiatives, known as “Track Two”, have often proved useful to conflict resolution efforts around the world.

The Political Situation in Myanmar

- Canada should continue to pursue a policy of active engagement with the Government of Myanmar and should continue to provide development assistance focused on the needs of all communities in that country. There is no conflict between our continuing advocacy for the rule of law, human rights, democracy and accountability and the needs of human development.

- Canada should continue to emphasize that a return of Rohingya refugees to Myanmar from Bangladesh has to be conditional on clear evidence that the recommendations of the Kofi Annan Commission to ensure the recognition of political and civil rights of the Rohingya in Rakhine State are being implemented on the ground, that a sustained international presence will be allowed, and that the return of the refugees will be voluntary, dignified, secure, and sustainable.

- Canada should continue to insist that humanitarian assistance and observers must be available to the whole population of Rakhine State, regardless of ethnicity. International assistance and the presence of observers need to be seen as pre-conditions to any repatriation of the Rohingya people to Myanmar. Funding will need to be provided to ensure such efforts are effective.

- Canadian development assistance to Rakhine State and the whole of Myanmar should be increased and should focus on the needs of women and girls, reconciliation, and the steps necessary to ensure the safety, security, and civil rights of the whole population, including the Rohingya. Special attention must be paid to the need for an emergency response for both Myanmar and Bangladesh.

- Beyond Rakhine, Canada should continue to support the broader peace process in Myanmar, with assistance to key stakeholders, civil society and those able to engage effectively with all the groups and regions in the country. Funding should also be provided for bona fide initiatives deemed to be making a positive contribution to the peace and reconciliation process.

- Given the role that the military continues to play under the existing constitution, consideration should be given to provide cross-accreditation to Myanmar of the Canadian Defence Attaché resident in Thailand, in order to increase more direct dialogue with the military wing of the Government of Myanmar in pursuit of Canada’s policy on human development and human rights.

The Question of Accountability and Impunity

- It is a fundamental tenet of Canada’s foreign policy that those responsible for international crimes, including crimes against humanity and genocide, must be held responsible for those crimes. In order to ensure accountability and to end impunity for violations of international law, concrete and specific actions are required, such as:

- a credible and effective process of investigation, which includes interviewing witnesses, collecting evidence and meticulous record keeping. Canada should work with like-minded countries to initiate such a process and as a matter of priority be prepared to contribute funding to it. This will require a willingness to work with like-minded countries, at the UN Human Rights Council, at the General Assembly, and at the Security Council to ensure that the most effective accountability mechanisms are put in place as soon as possible. This could include establishing a “Triple I-M” to collect and preserve evidence that could support case referrals to the ICC or to national jurisdictions carrying out prosecutions on the basis of universal jurisdiction;

- candid and direct discussions with governments, and all political actors, to ensure they are aware of the commitment of a number of countries, including Canada, to the need for accountability for violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law as set out in the Rome Statute, the UN Convention on Genocide, and other sources of international law.

- Individuals, organizations and companies deemed to have been involved in a breach of international humanitarian law, or other laws related to conflict, including breaches of the Rome Statute and the UN Convention on Genocide, should, in addition to the processes set out above, be subject to targeted economic sanctions. Canada should be actively working with like-minded countries to identify the individuals or parties that should be subject to such sanctions, which are likely to have more impact if multilateral in scope. Canada should also continue its arms embargo and should seek a wider ban on the shipment of arms to Myanmar.

Effective Coordination and Cooperation