Annual trade report: Highlights of Canada’s Merchandise Trade Performance in 2020

Kevin Jiang

March 2021

Table of contents

Highlights

- In 2020, total Canadian merchandise trade recorded the second largest one-year decline on record, plummeting by 10.9% to $1.06 trillion in value. Canadian merchandise exports contracted 11.8% and merchandise imports were down 9.9%.

- The crash was concentrated in the second quarter of 2020 resulting from pandemic containment restrictions as almost all the sectors posted declines in April.

- By the end of the year, merchandise trade had largely recovered in most sectors except for energy and aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts.

- By country, the United States contributed the most to the decline in Canadian exports, mainly due to sharp and sustained declines in energy and automotive products. By the end of the year, exports to the U.S. were down 10.5% compared to the level in February. On the other hand, annual exports to China improved drastically and exports to the EU held up well.

Overview

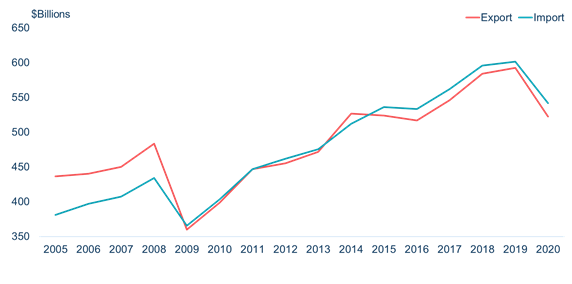

After recording three consecutive years of growth and reaching a record high of nearly $1.19 trillion in 2019, Canada’s total merchandise trade value plummeted in 2020, down by 10.9% to $1.06 trillion. This represents the second largest one-year decline on record after the 21.0% contraction in 2009. Moreover, Canada’s merchandise exports and imports both posted significant drops in 2020, down 11.8% and 9.9%, respectively. For both Canadian exports and imports, the value of annual merchandise trade was the lowest since 2016 (see Figure 1).

The decline was concentrated in the second quarter of 2020, when COVID-19 lockdowns at home and abroad severely impacted every aspect of the economy and disrupted international trade flows. Following gradual easing of restrictions, Canada’s merchandise trade begun recovering in the second half of the year with monthly trade slowly returning to pre-COVID levels by the end of 2020. As the annual decline in exports was more drastic than that of imports, Canada’s merchandise trade deficit more than doubled in 2020, widening to $19.5 billion—the largest Canadian merchandise trade deficit on record. In real (volume) terms, Canadian merchandise exports and imports fell by 6.7% and 9.4% in 2020, respectively.

Figure 1 – Annual Canadian Merchandise Trade, 2005-2020 ($ Billions)

Figure 1: Text version

| Export | Import | |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 436.35 | 380.86 |

| 2006 | 440.37 | 397.04 |

| 2007 | 450.32 | 407.30 |

| 2008 | 483.49 | 434.00 |

| 2009 | 359.75 | 365.36 |

| 2010 | 398.86 | 403.70 |

| 2011 | 446.71 | 446.67 |

| 2012 | 455.17 | 462.07 |

| 2013 | 471.95 | 475.66 |

| 2014 | 526.77 | 512.20 |

| 2015 | 524.07 | 536.15 |

| 2016 | 516.77 | 533.25 |

| 2017 | 546.09 | 562.03 |

| 2018 | 584.29 | 595.89 |

| 2019 | 592.65 | 601.69 |

| 2020 | 522.53 | 542.00 |

Data: Statistics Canada Table: 12-10-0011-01, Customs Basis.

Monthly Changes in Merchandise Trade in 2020Footnote 1

Before we turn to Canada’s annual trade performance, we will first examine how monthly trade evolved over the past 12 months. After posting a record high in 2019, Canada’s merchandise trade begun declining at the start of 2020. As a critical supplier in the global supply chain, China’s efforts to contain the spread of the coronavirus directly and indirectly contributed to the initial fall in Canada’s trade in Q1. As the viral disease ultimately travelled outside of the country and transformed from a localized health crisis to a global pandemic, governments around the world reacted by introducing COVID-19 containment measures. Canada was no exception. In March 2020, Canada implemented stay-at-home orders in high-risk zones, shutting down many factories, indoor activities, as well as discouraging all non-essential travel, largely putting the economy on hold, save for a few essential sectors. While this was necessary to contain the spread of the virus, its negative impact on the economy clearly affected trade. By April, 10 out of 11 export sectors in Canada and 9 out of 11 import sectors had posted declines compared to February levels. Footnote 2 Consequently, overall merchandise exports and imports plummeted, down 32.3% and 26.8% respectively in just two months. Low bilateral trade values persisted through the month of May but started rebounding in June and July. By the end of 2020, Canadian merchandise imports had mostly recovered while merchandise exports remained about 5% below February levels (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Monthly Canadian Merchandise Trade, 2020 ($ Billions)

Figure 2: Text version

| Export | Import | |

|---|---|---|

| Jan | 47.38 | 48.52 |

| Feb | 48.62 | 48.15 |

| Mar | 45.83 | 46.73 |

| Apr | 32.92 | 35.26 |

| May | 33.78 | 34.28 |

| Jun | 39.56 | 41.52 |

| Jul | 44.68 | 47.31 |

| Aug | 44.89 | 46.78 |

| Sep | 45.81 | 47.78 |

| Oct | 46.35 | 49.19 |

| Nov | 46.39 | 48.70 |

| Dec | 46.30 | 47.77 |

Data: Statistics Canada Table 12-10-0011-01, Customs Basis, Seasonally Adjusted.

The impact of the pandemic was unevenly felt across sectors in Canada. The most affected were the manufacturing sectors that produce durable goods and rely on international supply chains. The highly integrated North American automotive industry was one of the most affected. As most of Canada’s automotive products are traded with the United States, factories suspending production on both sides of the border during the initial wave of the pandemic led to a decline in two-way trade of motor vehicles and parts by 80%. However, as restrictions eased and production resumed, bilateral trade in automotive products quickly rebounded and managed to return to normal levels by the third quarter (see Figure 3). In contrast, trade in aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts recorded a 50% decline in April. But while imports rebounded briefly, two-way trade remained low by the end of the year. Compared to February, imports and exports in this sector were down 45.2% and 35.4% in December, respectively.

Figure 3– Monthly Canadian Merchandise Trade by Products, 2020

Figure 3: Text version

Motor vehicles and parts, Index (Feb 2020=100)

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export | 98.11 | 100.00 | 82.99 | 12.68 | 22.43 | 77.36 | 102.03 | 96.75 | 100.00 | 95.17 | 91.80 | 91.87 |

| Import | 100.01 | 100.00 | 88.28 | 20.86 | 18.28 | 58.54 | 91.15 | 92.23 | 94.63 | 95.75 | 95.00 | 97.17 |

Aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts, Index (Feb 2020=100)

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export | 76.14 | 100.00 | 65.44 | 44.05 | 56.94 | 56.74 | 76.56 | 65.73 | 68.85 | 61.01 | 59.32 | 64.61 |

| Import | 77.60 | 100.00 | 88.46 | 45.79 | 47.32 | 91.80 | 99.02 | 56.30 | 55.85 | 52.12 | 62.17 | 54.84 |

Data: Statistics Canada Table 12-10-0121-01, Customs Basis, Seasonally Adjusted.

Prices for commodities such as crude oil were also heavily impacted by the global pandemic. After a strong recovery in 2019, the average Western Canada Select price—benchmark for heavy crude oil obtained from Western Canadian producers, fell from US$41.1 per barrel in Q4 2019 to only US$16.4 per barrel in Q2 2020. This translated to a 42% decline in the export prices of crude oil and bitumen from February to April 2020. Combined with a significantly lower global demand for oil due to economic and travel restrictions, the value of Canadian crude oil exports crashed nearly 46% from February to April 2020. Furthermore, exports of other energy products like refined oil and natural gas also shrank. Overall, Canadian energy exports contracted by 37.3% over this period. Since then, energy price and volume have seen a moderate rebound. Nevertheless, by the end of the year, the value of Canadian energy exports was still down 18.3% compared to February 2020.

In contrast, sectors that produce essential goods and goods that improved quality-of-life during quarantine were largely spared of pandemic disruptions. Consumer goods, Canada’s largest import sector, performed exceptionally well. After a slight dip in April, monthly imports of consumer goods quickly rebounded and even surpassed pre-COVID levels on the back of increased shipments of medical supplies in response to the pandemic. Farm, fishing and intermediate food products was the only export sector and one of the only two import sectors that did not decline in April as demand for food rose due to the pandemic stirring fear over potential shortages. By December, exports in this sector were 19.9% above February levels and imports were 1.0% higher. Likewise, trade in electronic and electrical equipment and parts held steady throughout the year. Due to widespread lockdowns leaving large portions of the population housebound, demand for consumer electronics rose as people adapted to the new socially distant lifestyle and remote work. Other resource sectors such as forestry products and building and packaging materials, metal and non-metallic mineral products, and metal ores and non-metallic minerals were also relatively unaffected.

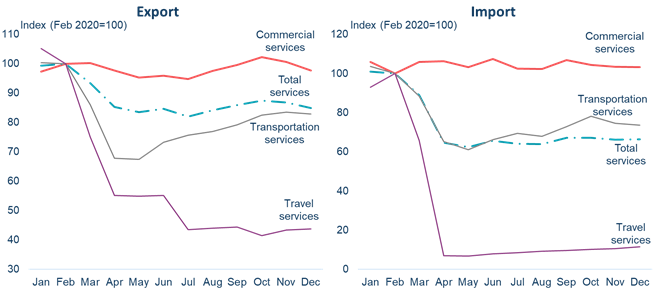

Services Trade Levels Remained Depressed Following Initial Drop

The most impacted sectors in Canada are in services, especially those that involve face-to-face interactions. For 2020 overall, Canadian services exports fell by 17.7% and services imports by 24.0% compared to the year prior. Both travel and transportation services plunged due to pandemic-related travel restrictions and remained far below pre-COVID levels by the end of the year. While there exists pent-up demand for travel, industry experts and private forecasters predict tourism and business travel will not completely recover for some time. On the other hand, commercial services held relatively steady during the year.

Figure 4 – Monthly Canadian Services Trade by Category, 2020

Figure 4: Text version

Export, Index (Feb 2020=100)

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial services | 97.29 | 100.00 | 100.24 | 97.66 | 95.31 | 95.93 | 94.76 | 97.59 | 99.68 | 102.33 | 100.63 | 97.68 |

| Total services | 99.32 | 100.00 | 93.37 | 85.27 | 83.55 | 84.72 | 82.02 | 84.15 | 85.89 | 87.51 | 86.89 | 84.92 |

| Transportation services | 100.36 | 100.00 | 86.11 | 67.79 | 67.50 | 73.23 | 75.73 | 76.95 | 79.17 | 82.53 | 83.54 | 82.96 |

| Travel services | 105.19 | 100.00 | 74.99 | 55.12 | 54.89 | 55.12 | 43.53 | 43.99 | 44.37 | 41.51 | 43.43 | 43.76 |

Import, Index (Feb 2020=100)

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial services | 105.89 | 100.00 | 105.94 | 106.42 | 103.22 | 107.40 | 102.52 | 102.26 | 106.89 | 104.38 | 103.57 | 103.34 |

| Total services | 101.07 | 100.00 | 88.98 | 64.79 | 62.48 | 65.69 | 64.19 | 64.02 | 67.22 | 67.24 | 66.30 | 66.38 |

| Transportation services | 103.67 | 100.00 | 88.56 | 65.27 | 61.21 | 66.34 | 69.46 | 67.96 | 72.93 | 78.14 | 74.55 | 73.60 |

| Travel services | 93.07 | 100.00 | 65.85 | 6.93 | 6.82 | 7.85 | 8.48 | 9.17 | 9.57 | 10.26 | 10.52 | 11.57 |

Data: Statistics Canada Table 12-10-0144-01, Seasonally Adjusted.

Annual Review

For 2020 overall, Canadian exports and imports posted the second largest annual declines on record. The value of Canadian merchandise exports fell 11.8% or $70.1 billion to $522.5 billion and merchandise imports were down 9.9% or $59.7 billion to $542.0 billion. Globally, largest declines in exports were to the United States (mainly energy and automotive products), Hong Kong SARFootnote 3 (gold), Saudi Arabia (aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts), Mexico (metal and non-metallic mineral products and consumer goods), and India (metal and non-metallic mineral products and energy products). Top declines in imports were from the United States (automotive and energy products), Mexico (automotive products), Japan (automotive products and machinery), France (aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts), and Germany (automotive products).

Americas: the United States contributed the most to the decline in Canada’s merchandise trade

Lower bilateral trade with the United States was the main reason for Canada’s annual decline in merchandise trade. Year-over-year, Canadian merchandise exports to the United States fell by 14.1% or $62.8 billion (almost 90% of the decline in Canada’s overall export value) to $383.8 billion—a level not seen since 2013. As a result, U.S. share of Canadian merchandise exports fell to 73.4%, the lowest on record. Similarly, Canadian imports from the United States registered a historical drop, down 13.5% in 2020 to $264.1 billion.

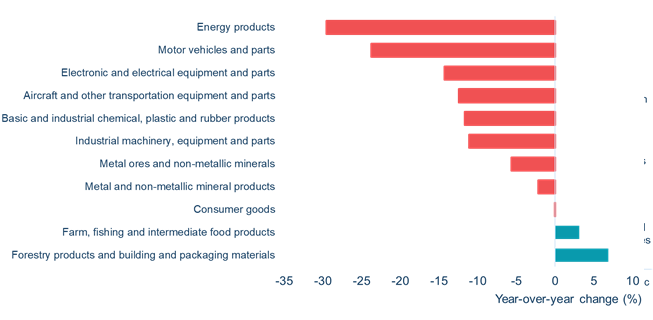

Automotive and energy are the two largest trade sectors between Canada and the United States. However, because of the heavily integrated supplies chains between the two countries, the various pandemic lockdown measures and the prolonged Canada-U.S. border closure led to a massive decline in two-way trade. For the full year, Canadian automotive exports to the U.S. fell 23.8% and imports fell 25.1%, and exports of energy products to the U.S. were down 29.5% and imports fell 37.1%. Lower trade in these two sectors with the United States was by far the largest contributor behind the decline in Canada’s overall merchandise trade in 2020. Other heavily impacted Canada-U.S. trade sectors include: industrial machinery, equipment and parts; aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts; and, basic and industrial chemical, plastic and rubber products (see Figure 5).

On the other hand, Canadian exports of forestry products and building and packaging materials to the U.S. posted a strong annual growth, up 6.9% or $2.2 billion in 2020. As a reliable supplier and the largest source for key forest products for the U.S. (e.g., softwood lumber and wood pulp), Canada fills in the gap between U.S. domestic supply and demand for forestry products. Moreover, as much of the personal protective equipment made on both sides of the border require forest products, this efficient and secure supply chain was made even more essential in the past year.

Figure 5. Annual change in merchandise exports to the United States, 2020

Figure 5: Text version

| Year-over-year change (%) | |

| Forestry products and building and packaging materials | 6.85 |

| Farm, fishing and intermediate food products | 3.09 |

| Consumer goods | -0.05 |

| Metal and non-metallic mineral products | -2.17 |

| Metal ores and non-metallic minerals | -5.66 |

| Industrial machinery, equipment and parts | -11.10 |

| Basic and industrial chemical, plastic and rubber products | -11.71 |

| Aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts | -12.44 |

| Electronic and electrical equipment and parts | -14.30 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | -23.76 |

| Energy products | -29.54 |

Data: Statistics Canada Table 12-10-0119-01.

The pandemic also shifted certain aspects of international trade for the United States. According to data from the United States Census Bureau, U.S. merchandise trade with China advanced 0.4% in 2020, while trade with its other main partners recorded significant declines. Consequently, China leapfrogged over Mexico and Canada to become the largest merchandise trading partner for the U.S. in 2020. However, a portion of this increase in trade can be traced back to elevated demand for medical supplies. Therefore, as the fundamentals of North American trade have not changed, this new trend is unlikely to be sustained after the pandemic.

Canadian merchandise exports to Latin America and the Caribbean contracted by 10.4% in 2020 to $13.7 billion. Mexico is Canada’s top export destination in this region, accounting for over 40% of the value in recent years. However, due to widespread declines over 2020, especially in mineral products and consumer goods, Canadian exports to Mexico fell by 16.2% or $1.2 billion (approximately three quarters of the export decline to the region). Excluding Mexico, Canadian exports to the region were down 5.1%, as lower exports to Brazil (energy products) and Colombia (aircraft and parts), were partially offset by higher exports to Chile (agri-food and energy) and Peru (agri-food). Over the same period, Canadian merchandise imports from Latin America and the Caribbean were down 11.7%. Lower imports from Mexico, especially in automotive products, were again the primarily reason for the decline in trade with the region.

Asia and Oceania: exceptional growth in trade with mainland China

Canada’s merchandise trade with Asia and Oceania held up relatively well in 2020, with exports falling by 5.9% or nearly half the rate of exports overall, to reach $60.8 billion. Imports were down only 1.4% to $136.8 billion. However, within the region, trade with China grew strongly while trade with other countries in the region suffered.

Following the largest fall on record in 2019, Canadian merchandise exports to mainland China rebounded in 2020, growing by 8.1% to reach $25.2 billion in value. This represents the largest annual growth out of Canada’s principal trading partners by far and pushed up China’s share of Canadian merchandise exports to 4.8%—the highest on record. Canadian exports were mainly supported by farm, fishing and intermediate food products (+38%); metal ores and non-metallic minerals (+35%); and consumer goods (+53%). At the same time, Canadian merchandise imports from China also increased, up 2.0% from 2019 to $76.5 billion in value, as higher imports of consumer goods (+12%, particularly medical supplies) were partially offset by lower imports of various manufactured products and metal and non-metallic mineral products.

Canada’s exports to other markets in Asia and Oceania did not perform well, with exports to all other top 10 markets in the region falling in 2020. Among the various products and sectors that were affected by the pandemic, lower energy exports were a top contributor to the export declines to the region. Canadian exports experienced significant declines in Japan (-2.1%), South Korea (-15.5%), and India (-24.0%). Exports to other keys markets like Australia (-5.8%, biggest declines were in machinery), Indonesia (-7.5%, forestry products), and Vietnam (-26.0%, energy) also deteriorated. Furthermore, as exports to Hong Kong recorded the largest percentage decline out of all of Canada’s principal trading partners (-52.7%),Footnote 4 it fell out of Canada’s top 10 export destinations in 2020, moving down 6 spots to the 16th place. In contrast, Canadian merchandise imports from this region performed better, with only Japan and Indonesia in the top 10 posting double-digit declines. It is especially worth noting that due to increased demand for medical supplies and other consumer goods in response to COVID-19, Canadian imports rose from large manufacturing suppliers in the region such as Vietnam (+16.6%) and Malaysia (+7.1%).

Europe: Canadian exports to the European Union held up exceptionally well in 2020

Canadian exports to the European Union (EU)Footnote 5 fell by just 2.6% year-over-year to $27.8 billion in value. Exports to large EU partners like Germany (consumer goods), the Netherlands (resource products), France (farm, fishing and intermediate food products), and Italy (consumer goods and cereals) even registered annual growth. Conversely, Canadian imports from the EU were down 12.2% for the full year, mainly because of decreased imports of automotive products, machinery, and energy products.

The United Kingdom (UK) officially left the European Union at the start of 2020. However, businesses in Canada continued to enjoy preferential access to the UK market (and vice versa) during the 2020 transition period, which concluded in December. Canadian exports to the UK rose marginally in 2020, up 0.6% to $19.9 billion, as a massive increase in shipments of gold was only partially offset by widespread declines, especially in exports of energy products. However, excluding gold (around three-quarters of the export value), Canadian exports to the UK fell by 17.3%. Over the same period, Canadian imports from the UK were down 15.0% to $7.8 billion. Looking ahead, the current benefits from the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) are expected to be maintained with the signature of Canada-UK Trade Continuity Agreement (UKTCA), allowing both countries to retain the status quo in the trade relationship.Footnote 6

Africa and Middle East: lower bilateral trade with Saudi Arabia dragged down trade with the region

In 2020, Canadian exports to Africa and the Middle East were down 13.0% to $9.8 billion in value. Following a huge spike in exports in 2019. Exports to the top market in the region, Saudi Arabia, declined by 44.8% or $1.3 billion in 2020, accounting for most of the decline in exports to the region. However, this decline can be almost entirely attributed to lower exports of armored vehicles. In contrast, Canadian exports to other top markets in the regions like Egypt (-4.2%, biggest declines were in aircraft and parts) and Algeria (-9.9%, cereals) recorded more moderate contractions or even improved in the case of United Arab Emirates (+17.8%, oilseeds) and Nigeria (+41.6%, aircraft and parts).

On the import side, Canada registered an increase in imports from Africa and the Middle East in 2020, up 5.4% to reach $10.2 billion. This was the only observed increase in imports out of all the major regions of the world. Increased shipments of precious stones and metals from African countries played a big role in this growth. South Africa led all countries in the region as Canadian imports from there nearly doubled in 2020, supported by increased imports of gold and platinum. Likewise, imports from Mauritania grew from less than $200 thousand in 2019 to $776.0 million in 2020 due almost entirely to gold. Similar to exports, imports from Saudi Arabia also declined, down 48.9% in 2020, primarily because of lower imports of energy products.

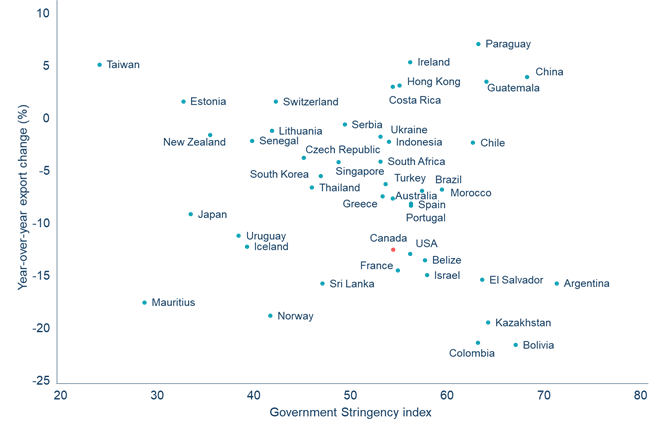

Global Restrictions to Contain COVID-19 Pandemic Impact Trade

Over the past year, governments around the world have tried to balance containment of the virus against its negative impact on the economy. Figure 6 shows the variations in national governments’ COVID-19 interventions versus the year-over-year declines in nominal merchandise export value. As of writing, out of the 44 markets that have reported full 2020 merchandise trade data, Canada ranks in at slightly higher than average for both the decline in exports and in the government stringency index. This means that Canada experienced larger declines in exports than average but also implemented stricter restrictions than the international average throughout the year. Within G20 members, Canada’s annual decline in merchandise exports was the fourth largest after Argentina, France, and the United States.

An earlier analysis conducted by the Office of the Chief Economist showed that increased COVID-19 economic restrictions during the period of January to September 2020 negatively affected international trade with that country (both imports and exports). In contrast, the number of COVID-19 cases per capita and COVID-19 economic stimulus in one country did not have a statistically significant impact on trade with that country when controlling for restrictions.

Figure 6 – Government stringency versus annual decline in export value, 2020

Figure 6: Text version

| Government Stringency index | Year-over-year export change (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 71.34 | -15.70 |

| Australia | 54.35 | -7.62 |

| Belize | 57.69 | -13.49 |

| Bolivia | 67.06 | -21.58 |

| Brazil | 57.37 | -6.88 |

| Canada | 54.44 | -12.52 |

| Switzerland | 42.29 | 1.61 |

| Chile | 62.67 | -2.30 |

| China | 68.27 | 3.98 |

| Colombia | 63.19 | -21.37 |

| Costa Rica | 54.39 | 3.05 |

| Czech Republic | 45.18 | -3.74 |

| Spain | 56.27 | -8.09 |

| Estonia | 32.70 | 1.63 |

| France | 54.90 | -14.47 |

| Greece | 53.30 | -7.42 |

| Guatemala | 64.05 | 3.50 |

| Hong Kong | 55.08 | 3.17 |

| Indonesia | 53.99 | -2.21 |

| Ireland | 56.18 | 5.39 |

| Iceland | 39.30 | -12.20 |

| Israel | 57.91 | -14.92 |

| Japan | 33.47 | -9.10 |

| Kazakhstan | 64.21 | -19.44 |

| South Korea | 46.94 | -5.48 |

| Sri Lanka | 47.08 | -15.72 |

| Lithuania | 41.88 | -1.16 |

| Morocco | 59.44 | -6.78 |

| Mauritius | 28.70 | -17.52 |

| Norway | 41.70 | -18.80 |

| New Zealand | 35.48 | -1.56 |

| Portugal | 56.26 | -8.28 |

| Paraguay | 63.21 | 7.12 |

| Senegal | 39.83 | -2.11 |

| Singapore | 48.76 | -4.15 |

| El Salvador | 63.59 | -15.37 |

| Serbia | 49.40 | -0.57 |

| Thailand | 46.01 | -6.58 |

| Türkiye | 53.61 | -6.24 |

| Taiwan | 24.03 | 5.15 |

| Ukraine | 53.11 | -1.71 |

| Uruguay | 38.41 | -11.16 |

| USA | 56.16 | -12.89 |

| South Africa | 53.10 | -4.09 |

*Stringency index ranges from 0 (least restrictive) to 100 (most restrictive). X axis values are the 2020 annual average government stringency index for each country.

Data: Global Trade Atlas; Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker.

Looking Ahead

Overall, like many aspects of the economy, Canadian merchandise trade suffered in 2020. However, looking at the trends in monthly trade, it is apparent that the recovery has already taken place in Canada with most sectors having returned or being in the process of returning to pre-COVID levels. Certain sectors like energy and services remain more impacted than the rest and face a more challenging road ahead. Nevertheless, much of the annual decline is directly or indirectly linked to the pandemic which is unlikely to bring significant structural shifts in trade. Moving forward, as long as the overall policy environment remains supportive and transparent, there is little evidence to suggest the impacts of this global crisis on trade will ultimately be long-lasting.

Appendix

A. Annual Trade by Sector

| Exports ($ Million, 2020) | Exports (∆%) | Imports ($ Million, 2020) | Imports (∆%) | |

| Total of all merchandise | 522,527 | -11.8 | 541,999 | -9.9 |

| Resource products | 286,983 | -10.9 | 168,345 | -8.2 |

| Farm, fishing and intermediate food products | 43,962 | 15.1 | 21,456 | 0.8 |

| Energy products | 88,889 | -28.6 | 22,892 | -38.7 |

| Metal ores and non-metallic minerals | 21,467 | -0.2 | 16,618 | 15.9 |

| Metal and non-metallic mineral products | 60,341 | -2.3 | 40,175 | 4.9 |

| Basic and industrial chemical, plastic and rubber products | 29,726 | -10.7 | 41,176 | -8.8 |

| Forestry products and building and packaging materials | 42,599 | -0.5 | 26,028 | -3.3 |

| Non-resource products | 210,196 | -13.6 | 362,394 | -11.2 |

| Industrial machinery & equipment | 32,043 | -14.4 | 60,634 | -12.8 |

| Electronic machinery & equipment | 23,026 | -13.5 | 68,221 | -5.6 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | 65,756 | -23.1 | 87,540 | -24.1 |

| Aircraft & other transportation equipment | 20,111 | -19.8 | 20,186 | -24.1 |

| Consumer goods | 69,260 | 1.0 | 125,813 | 1.2 |

Data: Statistics Canada Table 12-10-0121-01, Customs Basis.

B. Annual Trade by Principal Trading Partner

| Exports ($ Million, 2020) | Exports (∆%) | Imports ($ Million, 2020) | Imports (∆%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 383,795 | -14.1 | 264,121 | -13.5 |

| Mexico | 6,133 | -16.2 | 29,865 | -19.3 |

| Brazil | 2,143 | -5.0 | 6,573 | 21.4 |

| Peru | 872 | 13.4 | 3,664 | 2.1 |

| European Union | 27,774 | -2.6 | 59,876 | -12.2 |

| -Germany | 6,367 | 1.1 | 17,304 | -10.5 |

| -France | 3,708 | 1.9 | 6,467 | -25.6 |

| -Netherlands | 5,409 | 4.4 | 3,188 | -31.7 |

| -Italy | 3,692 | 13.9 | 9,002 | -4.9 |

| -Belgium | 2,574 | -20.0 | 4,351 | -12.3 |

| -Spain | 1,409 | -6.3 | 3,095 | -11.8 |

| United Kingdom | 19,911 | 0.5 | 7,839 | -15.0 |

| Norway | 2,537 | 17.8 | 1,177 | -22.5 |

| Switzerland | 1,798 | 25.4 | 5,883 | 18.9 |

| Russian Federation | 617 | -7.4 | 1,195 | -35.8 |

| China | 25,163 | 8.1 | 76,480 | 2.0 |

| Hong Kong | 1,903 | -52.7 | 572 | 51.0 |

| Japan | 12,359 | -2.1 | 13,570 | -17.7 |

| South Korea | 4,688 | -15.5 | 9,582 | 0.8 |

| India | 3,678 | -24.0 | 4,964 | -6.0 |

| Taiwan | 1,781 | -12.7 | 5,632 | -5.5 |

| Australia | 2,135 | -5.8 | 2,358 | 1.0 |

| Indonesia | 1,783 | -7.5 | 1,615 | -11.1 |

| Singapore | 1,235 | -18.9 | 1,179 | -3.9 |

| Algeria | 616 | -9.9 | 42 | -23.1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1,556 | -44.8 | 1,675 | -48.9 |

| Türkiye | 1,125 | -30.4 | 1,881 | -4.2 |

| Iraq | 88 | -40.1 | 1 | 25.0 |

Data: Statistics Canada Table 12-10-0011-01, Customs Basis.

Reference

Global Affairs Canada. “Canada-UK Trade Continuity Agreement (Canada-UK TCA) - Economic Impact Assessment.” https://www.international.gc.ca/gac-amc/publications/economist-economiste/state-of-trade-commerce-international-2020.aspx?lang=eng#24

Hale, Thomas, Thomas Boby, Noam Angrist, Emily Cameron-Blake, Laura Hallas, Beatriz Kira, Saptarshi Majumdar, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips, Helen Tatlow, Samuel Webster (2020). Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government. Available: www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/covidtracker

Scarffe, Colin (2020). “Have Countries’ Response to COVID-19 Affected Trade?” Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist.

Statistics Canada. Table 12-10-0011-01: International merchandise trade for all countries and by Principal Trading Partners, monthly (x 1,000,000).

Statistics Canada. Table 12-10-0119-01: International merchandise trade by province, commodity, and Principal Trading Partners (x 1,000).

Statistics Canada. Table 12-10-0121-01: International merchandise trade by commodity, monthly (x 1,000,000).

Statistics Canada. Table 12-10-0144-01: International trade in services, monthly (x 1,000,000).

Statistics Canada. Table 12-10-0126-01: International merchandise trade, by commodity, price and volume indexes, annual.

Statistics Canada. Table 12-10-0128-01: International merchandise trade, by commodity, price and volume indexes, monthly.

- Date Modified: